Competition and Cooperation in Liner Shipping

Chapter 14

Competition and Cooperation in Liner Shipping

William Sjostrom*

1. Introduction

Liner shipping is the business of offering common carrier ocean shipping services in international trade. Since it became an important industry in the 1870s, it has been characterised by various agreements between firms. Historically, since the formation in 1875 of the Calcutta Conference, the conference system was the primary form of agreement in liner shipping. Variously called liner conferences, shipping conferences, and ocean shipping conferences, they are formal agreements between liner shipping lines on a route, always setting (possibly discriminatory) prices, and sometimes pooling profits or revenues, managing capacity, allocating routes, and offering loyalty discounts. Conferences agreements were quite successful and in many cases have lasted for years. In the last two decades, conferences have begun to be supplanted by alliances (particularly in the American and European trades, where legislative changes have been unfavourable to them), which are less complete (they do not, for example, set prices) but encompass more broadly defined trade routes.

Section 1 will review cooperative agreements in the liner industry, including conferences and alliances, as well as the historical origins of that cooperation. Section 2 reviews the primary models that have been used to explain the conference system, including models of monopolizing cartels, contestability, destructive competition, and the empty core. Section 3 reviews a variety of practices and alleged practices in liner shipping, including predatory pricing, loyalty contracts, price discrimination, and price and output fixing. Finally, section 4 offers a brief conclusion.

1.1 Cooperation

International liner shipping has long been dominated by collusive agreements, originally conferences and more recently alliances. Conferences have been used since at least the 1870s, when the industry was being established. In recent years, these agreements have been supplemented and replaced by other kinds of agreements such as consortia and alliances. The focus of this chapter is on explaining the economic models of competition used to analyse cooperation in liner shipping for purposes of competition policy.

Conferences are organisations of shipping lines operating on a particular route. At different times, subject to various regulations, they have set tariffs, employing policing agencies to check on adherence to the tariff. Members have been fined out of the membership bonds they post.1 They may also allocate output among their members, by either cargo quotas or more commonly sailing quotas. If ships always sailed at the same capacity, which they do not, cargo and sailing quotas would be identical. Sailing quotas are, however, probably easier to enforce. They may also pool revenues and allocate particular ports on a given route.2 All of these practices have been used by conferences throughout their history. For example, in the late nineteenth century and into the beginning of the twentieth century, as part of the Calcutta Conference, the P&O, the BI, and the Hansa line had an agreement about the number of sailings each would make out of Hamburg.3

In the 1970s, liner consortia were formed by conference members as a supplementary means of conference enforcement.4 They are essentially a system of common agency. More significant has been the rise of the strategic alliance. They were first used in the 1990s,5 and there is some evidence that conferences are being displaced by alliances, perhaps because of the declining antitrust immunity of conferences. Alliances engage in cross route rationalisation, and there is some evidence that the rationalisation reduces costs by taking advantage of economies of density.6 Unlike conferences, they do not issue a common tariff, but they cover much broader trade routes. Only recently have economists begun to examine them. Unfortunately, the state of research is limited to a lot of speculation about their functions and effects, and a few facts, without substantial testing of models of alliances.

Speculation on the reasons for alliances has focused on risk reduction and scale economies. The claims about risk reduction focus on two issues. First, alliances give liners companies access to other routes without investing in ships, thereby reducing the risk of new investment.7 Second, by reserving slots on ships from other members of the alliance working other routes, liner companies reduce risk by diversifying into multiple routes.8

Although no evidence has been produced in support of the expansion explanation of risk, there is cross-industry evidence that firms use strategic alliances for this reason.9 Explanations that focus on diversifying through multiple routes face the problem that investors can already diversify their portfolios by investing in multiple lines on different routes. If there is evidence for this explanation, it will likely have to come from focusing on managerial risk. There is cross-industry evidence that managers with specialised skills diversify to protect themselves against bankruptcy and job loss.10

The claims about scale economies11 focus on economies in marketing and allocating ships to ports to reduce shipping time. The evidence available supports these explanations, with evidence that alliances reduce costs12 and raise capacity utilisation.13 How well these explanations work will, however, have to address the evidence that alliances are in decline over the last decade.14

1.2 Historical origins

Because sailing ships are subject to the vagaries of the wind, liner shipping offering regular scheduled service had to wait for the arrival of the steam vessel,15 although the thirteenth century Venetians operated what can be interpreted as a liner service to the eastern Mediterranean using a combination of oar and sail.16 Steam did not begin to be a competitor to the sailing ship until the development of the compound engine in the late 1860s and the triple expansion engine in the early 1880s.17 These developments substantially improved fuel economy and increased speed to about 10–12 knots. The compound engine cut fuel consumption by over half compared to a single cylinder steam engine. Essentially, it involved adding additional cylinders to the steam engine, each additional cylinder reusing steam before it cooled. The increase in fuel economy also expanded the space available for cargo. Steam vessels began to offer regular, scheduled service, i.e. liner service. It is in liner shipping that conferences have thrived.

Curiously, sailing vessels belonged to conferences operating on the UK–Australia route and the Germany–South America route,18 and there were early British coastal conferences involving sailing vessels as well.19 By and large, however, these were exceptions.

The UK–Calcutta conference is usually described as the first conference, and it is certainly the first modern conference. It started in 1875, consisting of five carriers: the P&O (Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Co), the BI (British India), and the City, Clan, and Anchor Lines. Within a decade or so, the conference extended its coverage of ports of origin from only the UK to the rest of northern Europe.

It was followed quickly by the development of other conferences. In the 30 years following the formation of the UK–Calcutta conference, conferences were formed on most of the major trade routes out of the UK and northern Europe. The Australia conference was started in 1884, the South African conference in 1886, the West African and northern Brazil conferences in 1895, the River Plate conference in 1896, the west coast of South America conference in 1904, and a conference covering the North Atlantic trade around 1900.20 Most of these conferences covered the outbound trade from Europe, leaving the inbound trades of mostly bulk commodities to tramp vessels.21

There were precursors, however. A conference from 1850 to 1856 on the North Atlantic involved the British and North American Steam Packet Company (the Cunard Line) and the New York and Liverpool United States Mail Steamship Company (the Collins Line).22 Glasgow ship owners may have fixed rates with a conference system in the 1860s.23 In addition, the Transatlantic Shipping Conference was formed in 1868. It was concerned, however, with issues such as uniform bills of lading and improving methods for inspecting cargo, and did not become involved in rate setting until 1902.24 Although conferences are generally associated with international shipping, there were precursors in British coastal shipping as early as the 1830s.25

Conferences were limited to the liner trades, without any success in the bulk trades.26 There were also conferences in the passenger shipping trade.27

It is commonly assumed by historians of shipping conferences that they were formed in response to excess capacity, typically based on documents produced by participants in the trade.28 A common version of this argument is that the opening of the Suez Canal, by shortening the distance between Europe and Asia, created excess capacity, but this version is not supported by the evidence.29 Sailing vessels could not use the Canal. Existing steamships had been built for short routes through the Mediterranean Sea or the Red Sea, and most of them were scrapped after the opening of the Canal. Moreover, after the opening of the Canal, there were increases in net steamship production, which increased later in the 1870s with the introduction of the double expansion engine. The continued steamship production is inconsistent with excess capacity.

One alternative to cooperation would be merger. Merger is generally a substitute for collusion, but it is not a perfect substitute because merger increases agency costs.30 The only known attempt to explicitly replace a conference with a merger was the largely unsuccessful International Mercantile Marine Company.31

The Ocean Shipping Reform Act of 1998 changed the treatment of conferences under American antitrust law, effectively eliminating the ability of conferences to control their members by mandating secret and independent action. EC regulation 4056/86, which gave conferences an exemption from EC competition law, was repealed effective October 2008. Given that agreements and mergers are substitutes, we should expect an increase in industry concentration. Sys32 shows that mergers have increased worldwide industry concentration, using a wide variety of measures, including the Gini coefficient and the Herfindahl index.

2. Alternative Models of Agreements

Most work on shipping conferences has involved four kinds of models: monopolistic cartels; contestable markets; destructive competitive; and empty cores.33 The argument that conferences are monopolistic cartels is at least as old as Alfred Marshall,34 who argued that conferences could act as monopolists because there were substantial scale economies in the industry that led to a small number of firms. Lenin and the Marxist historian J.A. Hobson described shipping conferences as vivid examples of the tendency toward the concentration of capital.35 The other explanations arose largely as responses to the cartel model. Destructive competition and its modern variant, the empty core, are alternative explanations of why conferences exist. Contestable markets have been used to criticise the proposition that conferences can usefully be described as monopolistic cartels. This matters for competition policy, because if conferences are not monopolising cartels, then competition policy need not address them.

Models of competition are important for making sense of the role agreements play in liner shipping, and seeing whether those insights can be generalised to other industries. They are also important for competition policy. Assuming that competition authorities are attempting to increase competition,36 it is important to establish whether a particular practice reduces competition rather than having an alternative purpose. If it can be established that a practice does not reduce competition, it needs no further analysis for purposes of competition policy.

The term “competition” is routinely used vaguely, with differing and sometimes inconsistent meanings. Sometimes it used simply to mean the number of sellers (both as a measure of concentration and as a measure of how far to the right the supply curve lies). Sometimes it is used to mean low measured profitability,37 which is taken to mean the absence of monopoly and monopoly profit. Sometimes it is used to mean that buyers have good substitutes; sometimes it is used simply to mean that the seller faces a downward sloping, rather than perfectly inelastic demand curve.

Rather than getting absorbed in a semantic debate, it is simpler and more useful to think about competition by the outcome: the mark-up of price over marginal cost.

2.1 Non-cooperative game-theoretic models of collusion: cartel enforcement

It is easy to get involved in pointless and unproductive discussions about what it “really” means to be a cartel. It is simpler to simply define a cartel, following the conventional practice of economists, as an agreement that attempts to get its members to act jointly as a monopolist. Agreements that serve other purposes, such as preventing destructive competition, reducing risk, or trade promotion, should simply be referred to as such.

In perfect competition, output allocation is simple and automatic. Each seller produces an output such that its marginal cost is equal to the market price. In a cartel, prices are increased, but output must be reduced. Therefore, each firm’s output must be centrally directed. Each firm produces an output such that marginal cost is less than the price, giving each firm an incentive to raise output and upset the cartel arrangement. The primary problem for any monopolising cartel is therefore enforcement. Enforcement means that output increases must be punished,38 but first they must be detected.39

One argument disputing the cartel explanation should be dispensed with quickly. A seller with market power will raise price until its rivals’ products are good substitutes. (It will raise price until marginal cost equals marginal revenue. Positive marginal cost implies positive marginal revenue, and positive marginal revenue implies an elastic demand.) The frequent assertion that conferences cannot be monopolies or monopolistic cartels because they face too many good substitutes40 may be the opposite: they face good substitutes because they act monopolistically.

A number of attempts have been made to test whether shipping conferences can be explained by cartel models. Fox measured the effect of the number of firms in a conference and a conference’s market share on freight rates.41 She finds that freight rates fall when the conference market share falls. She also finds that as the number of conference members rises, freight rates also fall, which is consistent with Stigler’s theory of oligopoly,42 specifically that increased numbers in a cartel increase the cost of coordination and therefore lower price.

In a separate paper, Fox looked at the provision in the US Shipping Act of 1984 that allows conference members to deviate from conference rates on ten days, notice.43 A cartel model would predict that allowing independent action, even though it is public rather than secret price cutting, should undercut conferences because it makes enforcing the conference tariff more difficult. She fails, however, to find evidence that the Act made any difference at all to conferences.

Paul Clyde and James Reitzes, in an ingenious study, distinguished between increased freight rates because of increased conference market share and because of increased market concentration.44 They find statistically significant but economically insignificant effects of increased market concentration on freight rates, but, contrary to the results in Fox, no effect of increased conference market shares on freight rates.

It is worth emphasising that focusing on price can be misleading. Conferences can raise price because they restrict output (making shippers worse off) or because they add value, thereby raising demand and raising output. A better test would be to focus on the effect of conferences on output. Some insight can be gained from a study of trans-Atlantic passenger shipping cartels in the first decade of the twentieth century.45 The authors estimated that westward migration fell by 20–25% because of the passenger cartels operating that decade.

Deltas, Serfes, and Sicotte took a historical approach, using a sample of 47 pre-World War I conferences.46 They looked for reasons why a cartel might be easier to negotiate and enforce, arguing that a cartel can then successfully impose stricter, less flexible terms on its members. Enforcement is easier if there is multi-market contact. The basic intuition is that punishment for deviations from a cartel agreement in one market can be carried out in several markets. It also argues that enforcement is also easier if one or more of the firms has a large global market share. In that case, it is easier for the large firm to transfer ships to a market to carry out punishment. Agreements are easier to negotiate if there are a small number of firms and if there is heterogeneity in size, allowing a large firm to dominate the agreement. A strict, inflexible agreement is also more sustainable if entry is less likely.

This argument should not be confused with the idea that a firm operating in multiple markets can cross-subsidise predatory pricing to prevent destabilising entry. Gordon Boyce47 argues that because the International Mercantile Marine (a combination of five transatlantic lines sponsored by J.P. Morgan formed in the period 1900–1902) ran diversified lines from the UK to Canada, the US, and Australasia, it could use cross-subsidization to harm smaller, single route firms. Boyce’s argument requires highly inefficient capital markets, because both the predator and its victim are borrowing for a price war. The predator is merely borrowing from its own income stream.48

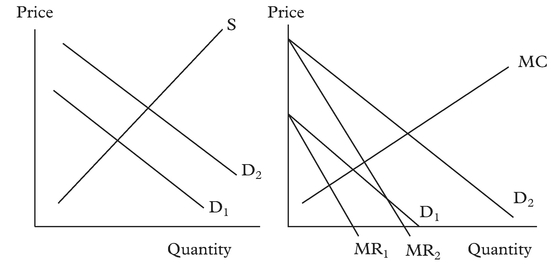

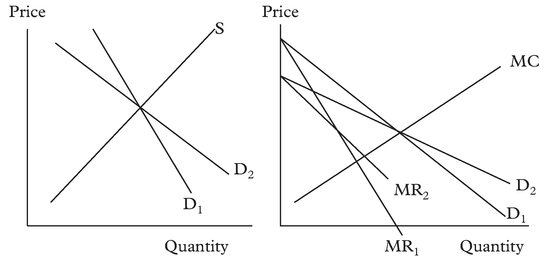

A different approach is to use developments in what has been called the New Empirical Industrial Organization. The approach can be seen in Figures 1 and 2. In models of monopoly and of perfect competition, an increase in demand raises price and output, and a decrease in demand lowers both, as shown in Figure 1. Therefore, the consequences of a rise or fall in demand cannot separate the two models. Suppose instead that

the demand rotates (becoming steeper or flatter). In a model of perfect competition, this does not raise or lower price or output. In a model of monopoly, however, flattening the demand curve raises marginal revenue relative to demand, thereby lowering price and raising output. Making demand steeper lowers marginal revenue relative to demand, thereby raising price and lowering output. This can be seen in Figure 2.

Start by writing the market demand curve as P(Q), so that price depends on quantity sold. The slope of the demand curve is ΔP/ΔQ. Marginal revenue is P + (ΔP/ΔQ)Q. The second term is the difference between marginal revenue and price. Static oligopoly models predict how much of that difference is perceived by sellers. Let λ be the fraction of that difference that is perceived by sellers. The marginal revenue as perceived by sellers is P + λ(ΔP/ΔQ)Q.

Different oligopoly models imply different values of λ. In monopoly, the whole marginal revenue is perceived, so λ = 1. In perfect competition (or Bertrand Nash equilibrium), none of the marginal revenue is perceived (marginal revenue is simply market price), so λ = 0. In Cournot Nash, the economist’s standard model of noncooperative equilibrium, λ is the Hirshman-Herfindahl index (the sum of the squared market shares).49

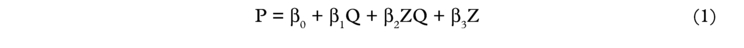

The value of λ is found by equating perceived marginal revenue to marginal cost. As a simple example, suppose the demand curve is:

where P is price, Q is output, and Z is a demand shifter. Note that the slope of the demand curve is β1 + β2Z, so that Z can also rotate the demand curve, as in Figure 2 above.

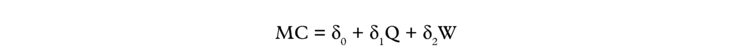

Given the demand equation, marginal revenue can be written as P + (β1 + β2Z)Q, and therefore perceived marginal revenue can be written as P + λ(β1 + β2Z)Q. Write industry marginal cost as:

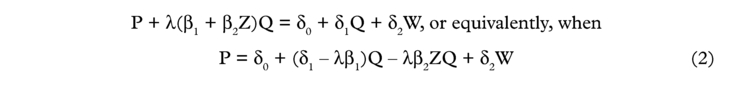

where W measures some input price.50 (If δ1 = 0, then marginal cost is constant.) Profit is maximised when perceived marginal revenue equals marginal cost, that is, when:

Equation 1 (the demand function) and equation 2 (the profit maximisation condition), can be estimated jointly, and λ can be estimated from the ratio of the coefficient of ZQ in equation 2 (– λβ2) to its coefficient in equation 1 (β2).51

One important drawback to this approach is that the value of λ is not clearly specified in a cartel model, and that poses a problem for measuring whether agreements in liner shipping are cartel arrangements. A costlessly enforced cartel would have λ = 1, that is, it would behave like a monopolist. It would equate industry marginal revenue to industry marginal cost. Note that equating marginal revenue to marginal cost is the same as setting marginal revenue minus marginal cost (i.e. marginal profit) equal to zero. At the industry profit maximum, a small increase in output costs roughly zero in profits. Cartel enforcement is not costless, however, because setting price above marginal cost gives cartel members an incentive to cheat. At the industry profit maximum, a small increase in output does not lower profits, but preventing it incurs positive enforcement costs. It follows that the cartel equilibrium involves higher output and lower price than the monopoly equilibrium.52 The economic theory of cartels tells us λ will be less than one and greater than its non-cooperative equilibrium value, but little beyond that. Where it lies in between those two values depends on the costs of cartel enforcement.

These techniques allow both a measure of the extent of competition in the market and a way to test alternative theories of markets. Even though cartel models do not make a specific prediction about the value of λ, the models are good for estimating how, for example, various legislative changes alter the value of λ. Using these techniques, Wilson and Casavant53 offered evidence that the US Shipping Act of 1984 raised the value of λ (in other words, raised prices), except where the Act explicitly allowed conference members to independently deviate from conference rates, in which case it lowered λ (in other words, lowered prices). Unfortunately, although this approach could tell us a lot about the effect of regulation in the industry, Wilson and Casavant are the only authors I am aware of who apply these techniques to liner shipping.

Now that these techniques are laid out in detail, there is scope for more formal testing of a variety of questions about competition, including the assumption that bulk shipping is best explained by models of perfect competition.54

2.2 Non-cooperative game-theoretic models of collusion: contestable markets

The theory of contestable markets focuses heavily on sunk costs. It draws on the insight that potential competitors are a constraint on pricing behaviour as much as actual competitors. Suppose in a market there are no sunk costs and incumbent firms do not respond to entry by lowering prices. Then entry is costless in the sense that all costs of entry can be recovered on exit. Entry is therefore riskless. Moreover, the entrant can make its entry decision without regard to strategic decisions by the incumbent.

Suppose a market had only one seller. The seller could not act as a monopolist because an entrant would undercut it. If entry is costless, schemes to exclude entry do not work because the entrant cannot be threatened with losses on entry. Should the entrant face the prospect of losses, it can always costlessly depart until the problem goes away.

John Davies has focused attention on the degree to which liner firms face sunk costs, and the risks of retaliatory price-cutting.55 He has provided evidence that sunk costs are low, and that retaliation is slow. That is, he has shown that the assumptions of contestability are roughly satisfied by the liner market. If the liner market is contestable, then conferences may have difficulty acting like monopolising cartels. Whatever service they provide, they must do so at (economic) cost, lest they are uncut by entry.56

An important, unresolved difficulty is how sensitive contestable markets to deviations from the assumptions of zero fixed costs and no retaliatory pricing. There are theoretical grounds for believing that very small deviations from these assumptions can have large consequences for contestability,57 but little effort has been made to empirically quantify the problem.

2.3 Destructive competition

Destructive competition arguments come in two forms. The usual form among maritime economists focuses on high sunk costs, inelastic demand, and the risks to carriers of “overtonnaging” or excess capacity. (The next section discusses another version, the theory of the core.) Daniel Marx is the primary early exponent,58 and the argument has been made by industry practitioners.59 Maritime historians have tended to favour this argument as well.60 In this argument, because a large proportion of costs is sunk, it follows that price would have to fall substantially before sellers would leave the market. Brooks argues:

“The high barriers to exit give shipowners reasons to delay capacity reduction; unless prices are good for scrap or the second-hand market is buoyant, there is a tendency to hope that a redeployment opportunity will materialise or be created. This results in an industry with an almost perpetual state of capacity oversupply.”61

The assertion of high exit barriers implies inelastic short run market supply. It is frequently asserted that the demand for liner shipping services is highly inelastic. A combination of inelastic supply and demand leads to a highly unstable price. Therefore, carriers are exposed to increased risk of losses, and shippers face substantial uncertainty about freight rates. On this explanation, conferences offer reduced risk to both carriers and shippers.

This explanation suffers from two serious flaws.62 First, if fluctuating prices lead to periods of losses, then they must also lead to periods of offsetting gains. Carriers will not enter unless the risk-adjusted present value of profits is positive. If long run changes in the market occur such that the present value of profits is negative, firms will (efficiently) leave the market, and the losses are their signal to do so.63 Second, if shippers valued rate stability, they could write forward contracts.

2.4 Cooperative game-theoretic models of collusion: the empty core

A more recent and theoretically coherent revival of the idea of destructive competition is the theory of the core,64 which has been applied several times to conferences65 and alliances.66

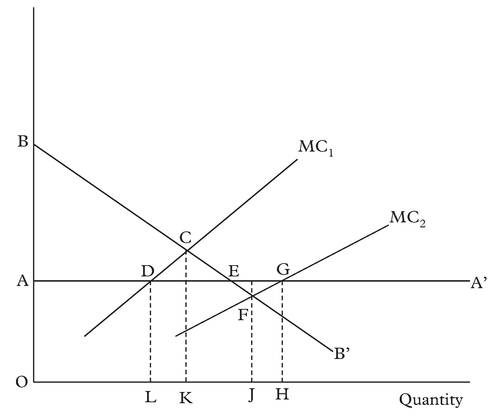

The theory of the core focuses on avoidable fixed costs and the integer problem (the number of firms in an industry must be an integer). With avoidable fixed costs and rising marginal cost, the relevant average cost curve is U-shaped. No output will be produced at any price below minimum average cost. When price rises to a firm’s minimum average cost (p*), that firm will enter at the output q* where average cost is minimised. The firm will produce q ≥ q* if p ≥ p*. Under perfect competition, the firm’s output will therefore be either 0 or q ≥ q*. Suppose firms are identical. Then at p*, industry output must be an integer multiple of q* (the integer problem). It would be only by chance that demand at p* would be an integer multiple of q*. It is therefore possible that demand and supply would not intersect. The problem would go away if a firm were willing to produce a fraction of q*, but avoidable fixed costs mean that no firm could profitably do so.

If inventories were inexpensive, a firm could produce only part of the time and provide a fraction of q* with inventories. In transportation industries especially, however, output is cargo or passenger space. Once the ship or airplane leaves, empty space is gone, so inventories are impossible.67 The only way to create inventories is to have excess capacity, which can lead to an empty core.

The integer problem does not necessarily lead to an empty core, but is likely to under some circumstances. Consider an example attributable to George Bittlingmayer.68 Suppose taxis can carry at most two passengers, and that the cost of a taxi trip is independent of whether there are zero, one, or two passengers. Admittedly, these assumptions are likely to be factually inaccurate. Most taxis can squeeze in an extra passenger in a pinch, and extra passengers reduce mileage. These assumptions, however, capture the same points that a more realistic but also more complex model would. First, there are some scale economies: once a taxi carries one passenger, the marginal cost of a second is less than the average cost.