Clinical Negligence and Poor Quality Care: Is Wales ‘Putting Things Right’?

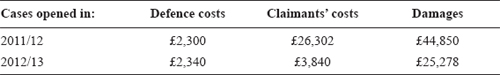

Chapter 9 The NHS in Wales, in common with other jurisdictions, is experiencing unprecedented numbers of clinical negligence claims. A range of solutions has been sought throughout the world to address the need to compensate patients who suffer injuries in the course of medical treatment, while keeping control over the escalating cost of redress. In 2011, Sheila McLean chaired a Working Group tasked with investigating the potential benefits of a no-fault compensation system for patients in Scotland alongside existing clinical negligence arrangements. Her carefully considered report contains a section dealing with the proposed solution in Wales for handling low value claims. Her committee advised on the key principles and design criteria that might be adopted for a no-fault compensation scheme, and recommended the introduction of a scheme based on a modified version of the model currently in operation in Sweden.1 In the same year, a far more conservative approach was introduced in Wales through a new system which had recently been implemented following the NHS [National Health Service] Redress (Wales) Act 2006, entitled Putting Things Right, aimed at dealing with lower value claims alongside concerns raised by staff and complaints by patients about poor quality care. McLean’s Report indicates that lawyers and policy makers in Wales and Scotland recognise that it is not only financial compensation that is required, but also the restoration of individuals who have suffered harm to the position they had been in prior to the injury, as far as this is possible.2 This chapter explains the origins and rationale of the new system in Wales, and attempts at this very early stage to assess its success to date. It also considers the implications for other jurisdictions in the light of the Francis Inquiry Report in 2013 on events at Mid Staffordshire. The constituent countries of the UK are becoming increasingly diverse in their approaches to the delivery and structure of their National Health Service responsibilities, as is exemplified by the legislative frameworks for healthcare in each country. Since the media focus tends to be centred on England, developments in Wales are little-known and seldom discussed outside the Principality, so it is necessary to describe the background to the reforms in Wales at this stage. Under the arrangements for devolution, a separate Assembly for Wales was created by the Government of Wales Act 2008 after a referendum was passed accepting the proposals made soon after New Labour came into power. However, there was no provision in that Act for separation of the legislature from the executive. The Welsh Assembly assumed the statutory powers and duties of the Secretary of State for Wales, but in practice the Assembly delegated most of its executive powers to the Assembly Ministers. The Assembly also assumed a large number of powers to make law by means of secondary legislation, but it had no power at that stage to make any primary legislation. A Commission appointed in 2002 to review the operation of devolution in Wales recommended that the Assembly should be replaced by two separate bodies – an executive and a legislature, and that by 2011 the Assembly should be able to make primary legislation for Wales.3 On 3 March 2011, a referendum on extending the law-making powers of the National Assembly for Wales was held in Wales, and there was a majority vote in favour of allowing the Assembly to make laws on all matters in the 20 subject areas for which it already had powers – which include health. Therefore the Assembly is now able to make laws without the requirement that there should be agreement by the Westminster Parliament, subject to standing orders. This is similar to the existing UK system in Westminster where Bills can be introduced by Government or private members. However, only the UK Parliament is able to make laws in areas that are not devolved, such as defence and taxation. The UK Parliament will not make laws for Wales on subjects concerning which the Welsh Government already has powers, without obtaining the agreement of the Welsh Government that it can do so. Despite this simplified approach, there is still a complex patchwork of legislation and delegated legislation relating to Wales. Devolution has enabled the NHS in Wales to take what in many respects is a radically different approach to that in England, while remaining true to the basic principles on which the NHS was founded. The vision for the present structure of healthcare services in Wales was explained by Edwina Hart, the then Welsh Health Minister, as bringing to an end the internal market in NHS services in Wales, ensuring that within each of seven geographical areas, one organisation would deliver all healthcare services, allowing for greater uniformity in the approach to delivering healthcare. Wales was prepared to take time in the development of these services to guarantee that there would be an NHS structure in place that would endure for the next 20 to 30 years. Since 2010, the Welsh structure has been based on a framework for delivering healthcare through seven Local Health Boards, with NHS Trusts being responsible for delivering ambulance services and certain tertiary services. Policy variations between England and Wales have resulted not only in completely different structures for healthcare delivery, but also in differences of emphasis and changed priorities in relation to healthcare. To take but a few examples, Wales has a new system for dealing with people suffering from mental illness, introduced by the Mental Health Measure 2009, much of which has been in force since 2012. Although the Mental Health Act 1983 remains in force in Wales, the Mental Health Measure makes a number of important changes to the way people with psychiatric problems can access and receive primary and secondary mental health services. Prescriptions have been free of charge in Wales since April 2007, as have dental check-ups for all residents under the age of 25 and over the age of 60. Car parking at hospitals in Wales is free of charge. Welsh NHS patients are being given a voice in Wales through Community Health Councils, which have been retained, and through extended advocacy arrangements for the people in hospital who are suffering from mental illness. There are different NHS complaints systems in England from Wales and different approaches to organ donation, specifically in recent legislation introduced in Wales to implement a system of presumed consent.4 The approach in Wales to handling concerns and claims now differs in many respects from that in England, and it is the new system, introduced in 2011, based on a policy document entitled Putting Things Right which lies at the heart of the discussion in this chapter. Despite variations in healthcare policy between England and Wales, all the UK countries share many common problems, which include serious concerns about pressures on ‘accident and emergency’ departments and out-of-hours provision for patients who seek treatment outside the normal working day for general practitioners. There is also disquiet about waiting-lists for surgery in the light of increasing demands for unscheduled care and the shortage of doctors in the UK as a whole. These factors can create a climate in which it is more likely that mistakes will be made, some of which will inevitably cause harm to patients, and there are common problems involving errors made in healthcare settings. Inhumane treatment and the avoidable deaths of some patients in certain NHS hospitals, which became a national scandal, resulted in the Francis Inquiry and subsequent Report, published in February 2013.5 Although this focused on events at the Mid Staffordshire NHS Trust in England, the other UK countries are anxious to learn lessons from the Report and its recommendations. Coupled with the issues highlighted in this Report are concerns about the rising cost of defending claims and compensating patients injured in the course of healthcare. Wales, in common with other jurisdictions in Europe and the United States of America, is experiencing an unprecedented rise in the volume of claims for clinical negligence, coupled with an increasing number of complaints about healthcare treatment and services. Data analysed by the Working Group chaired by Sheila McLean indicated that the volume of claims and compensation payments have risen in Scotland over the past decade in parallel with those in other jurisdictions.6 Over the past three years, payments to claimants in Wales have doubled, mirroring figures in England,7 to reach a total of £89m in the three-year period to April 2010.8 This resulted in an increase of £16m in funds paid by the Welsh Government to the Welsh Risk Pool.9 Another worrying feature of the present system is that the cost of defending claims frequently exceeds the value of the claim itself. As in other UK jurisdictions, the reasons for these recent developments are complex, and have been attributed to numerous factors, including the popularity of ‘no-win, no-fee’ cases, higher awards to take account of increased life expectancy of claimants, and the high cost of care and specialist equipment, particularly for those who suffered brain injuries at birth. Over the past 30 years, societal change and attitudes to compensation have resulted in a culture in which many patients who suffer injury in the care of the NHS expect to be compensated. Scotland, like England and Wales, currently has a system that covers compensation by the state for clinical negligence claims against NHS employees, including medical, dental and nursing staff, and Health Boards fund the defence of claims, being protected against disproportionate losses by the mandatory Clinical Negligence and Other Risks Indemnity Scheme (CNORIS). As in the other UK countries, General Practitioners (GPs) and other primary care contractors are separately insured. Liability for Health Boards is handled by the Central Legal Office.10 Although there has been no attempt to introduce comprehensive reform in Wales, a new scheme has recently been implemented under the NHS Redress (Wales) Measure 2008 which promotes early settlement of lower value claims. The history of this legislative development is interesting,11 and can be traced back to August 2001, when the Chief Medical Officer published Call for Ideas,12 inviting patients, NHS staff, the public and other key stakeholders to express views on the way in which the NHS should handle clinical negligence incidents in the future. His recommendations for reform were published in 2003 in Making Amends,13 a Consultation Paper stating proposals for reforming the system for dealing with clinical negligence in the NHS. The NHS Redress Act 2006 gives effect to the proposal in Recommendation 1 that an NHS Redress Scheme should be introduced to instigate appropriate investigations when things go wrong, and to provide remedial treatment, rehabilitation and care where needed, with suitable explanations and apologies, and financial compensation if necessary in certain cases. The proposed system would therefore combine complaints handling with compensation and remedial treatment. The 2006 Act provides for a ‘scheme’ to be established to enable the settlement of certain claims without the need for court proceedings. Section 1 of the Act states: (1) The Secretary of State may by regulations establish a scheme for the purpose of enabling redress to be provided without recourse to civil proceedings in circumstances in which this section applies. (2) This section applies where under the law of England and Wales qualifying liability in tort on the part of a body or other person mentioned in subsection (3) arises in connection with the provision, as part of the health service in England or of qualifying services. In terms of the qualifying liability in tort, the Act refers broadly to personal injury or loss arising out of a breach of a duty of care owed to any person in connection with the diagnosis of illness, or the care or treatment of any patient and in consequence of any act or omission by a healthcare professional. It does not apply in connection with primary care. The Act establishes the parameters of the cases to which any such scheme can apply, stating which bodies can be members of a scheme, and giving the Secretary of State power to make regulations governing the detailed rules for the operation of the scheme. To that extent this is a framework Act, annoyingly avoiding specifying details of the schemes that can be made under it. The powers given to the Secretary of State include the power to place new duties on scheme members and the Commission for Healthcare Audit and Inspection (then known as the Healthcare Commission, and replaced later by the Healthcare Commission and the Commission for Social Care Inspection, and finally by the Care Quality Commission in 2009)14 to consider whether cases or complaints fall within a redress scheme and if so, to take appropriate action. The ‘redress’ envisaged by the Act is clarified to some extent in section 3, by stating15 that a scheme must provide for redress ordinarily to comprise – (a) the making of an offer of compensation in satisfaction of any right to bring civil proceedings in respect of the liability concerned, (b) the giving of an explanation, (c) the giving of an apology, and (d) the giving of a report on the action which has been, or will be, taken to prevent similar cases arising. In addition,16 a scheme may, in particular – (a) make provision for the compensation that may be offered to take the form of entry into a contract to provide care or treatment or of financial compensation, or both; (b) make provision about the circumstances in which different forms of compensation may be offered. A scheme can specify the matters in respect of which financial compensation may be offered, and provide details about the assessment of the amount of financial compensation, also specifying an upper limit on the amount of financial compensation that may be included in an offer under the scheme. Under s. 3(5)(b), if a scheme does not specify a limit, it must specify an upper limit on the amount of financial compensation that may be included in such an offer in respect of pain and suffering; and s. 3(5)(c) provides that it may not specify any other limit on what may be included in such an offer by way of financial compensation. Wales took the initiative before England to construct a scheme, and the Welsh Assembly Government established the Putting Things Right project which considered the way in which the NHS in Wales handles concerns, and made recommendations for dealing effectively with such issues, using methods of investigation that were proportionate and would lead to appropriate remedies for patients and service users. The work undertaken in advance of the new scheme included a review of a pilot project in Wales entitled Speedy Resolution, for dealing with uncomplicated claims against the NHS, valued between £5,000 and £15,000 which had been in existence since 2005. That scheme had been introduced in response17 to a report by the Auditor General for Wales18 which had pinpointed administrative problems within the existing system, and fears for the future of the NHS in the light of financial projections based on the rising number of clinical negligence claims. The Speedy Resolution Scheme shared many of the objectives of the scheme proposed under the NHS Redress Measure, as it had been designed to provide a quick, proportionate and fair means of resolving low value claims in Wales for clinical negligence, and it also aimed at dealing with concerns about the rising costs of defending claims, about the time taken to settle and the need to provide adequate explanations to patients who suffered harm. The Speedy Resolution Scheme also encouraged NHS bodies to provide explanations to patients who had expressed concerns about their care, and apologies where appropriate, advising the use of action plans as a means of learning from mistakes and reducing the number of future claims. An evaluation of this scheme by stakeholders concluded that it had proved beneficial in some respects to both claimants and defendants.19 The scheme was considered, on balance, to have provided a realistic alternative to litigation, offering certain benefits, particularly in reducing costs and in establishing a structured framework for dispute resolution and dealing with claims in a timely fashion. The view was that: An obvious benefit provided by the Scheme is that in those claims where compensation is paid to a claimant the relationship between the award and costs is more proportionate when compared to non-Scheme claims. To this extent the Scheme is meeting with one of its objectives: of providing a proportionate means of resolving low value straightforward clinical negligence claims against the NHS in Wales. The researchers concluded that the scheme was ‘meeting its objective of providing a quick, proportionate and fair resolution of straightforward low value clinical negligence claims’ was generally fit for purpose, and should continue to apply in Wales. However, the evidence on time-scales indicated a problem in connection with procedural delay in respect of the admission stage. Delay at this point would ultimately contradict the notion of ‘speedy resolution’, and the delays in obtaining medical reports gave still greater cause for concern, prejudicing the overall objective of meeting the 61-week overall timescale. Under the Welsh scheme, which is still entitled Putting Things Right

Clinical Negligence and Poor Quality Care: Is Wales ‘Putting Things Right’?

Introduction

The Structural Context

Common Problems

Concerns, Complaints and Clinical Negligence Claims

The Attempt at a Solution in Wales

The Structure of the Redress Scheme