Charities

Chapter 15

Charities

Chapter Contents

First Requirement of Charitable Status: There Must Be a Charitable Purpose

Second Requirement of Charitable Status: There Must Be Public Benefit

Third Requirement of Charitable Status: The Objects Must Be Exclusively Charitable

As You Read

Look out for the following key issues:

how charities are administered and the advantages of having charitable status; and

how charities are administered and the advantages of having charitable status; and

the three essential requirements that an organisation must possess to be defined as a charity under the Charities Act 2011. These are that the organisation must:

the three essential requirements that an organisation must possess to be defined as a charity under the Charities Act 2011. These are that the organisation must:

– have a charitable purpose (as defined under s 3(1) of the Act);

– be shown to benefit the public (as required under s 2(1)(b) of the Act); and

– be wholly and exclusively charitable.

Background

The first example of Parliament recognising what was, at the time, a charity, was set out in the Preamble to the Statute of Charitable Uses Act 1601 (sometimes colloquially known as the ‘Statute of Elizabeth’). This Preamble contained a list of what was, in Elizabethan times, seen to be charitable although, as Lord Macnaghten pointed out in The Commissioners for Special Purposes of the Income Tax v Pemsel,1 the courts had recognised that charities could exist long before the 1601 Act. The courts used the Preamble to recognise those organisations or gifts as having charitable status if they either fell within the list contained in it, or fell within the ‘spirit and intendment’ of that list.

Making connections

You should remember from your studies of the English legal system that it is, of course, not usual for the Preamble of an Act to have such a prominent role as the one to the Statute of Charitable Uses 1601 enjoyed. The Preamble to an Act usually has no legal status and is usually an explanation of why the Act was enacted. But not only did the courts define whether an organisation or gift had charitable status by considering whether it fell within the definition in the Preamble, they also asked whether organisations or gifts of a similar nature to those set out in the Preamble could have charitable status.

Perhaps even more surprising is that the Preamble has been repealed (by the Charities Act 1960) and yet it is still referred to in the most modern of legislation: see s 1(3) of the Charities Act 2006.

Nowadays whether something enjoys charitable status is governed by the requirements of the Charities Act 2011. Section 2(1) sets out that, to enjoy charitable status, two requirements must be satisfied: (i) there must be a charitable purpose permitted by law; and (ii) there must be an element of benefit to the public in the work the organisation will undertake.

Charity Administration

Charities are an important part of today’s society. There are, as of 2012, over 161,000 charities registered with the Charity Commission.2 As will be shown, not all charities have to be regis-tered with the Charity Commission, so the total number of charities will be even higher.

The advantages of enjoying charitable status

There are several advantages of having charitable status, the most important being (i) taxation and (ii) legal.

Taxation

Generally, any income received by individuals or companies in England and Wales is subject to taxation. The rates of tax may change in the annual Budget delivered by the Chancellor of the Exchequer. For example, if you are in paid employment and earn over £8,1053 you will have to pay tax on that income. Similarly, if you own shares and the company declares a dividend, that will result in income being paid to you, which again will be taxed.

Charities enjoy substantial tax relief on income they receive, provided that income is used for charitable purposes. For example, if a charity holds land which it rents out (such as, for instance, the National Trust), no tax will be payable on the income, provided it is only used for charitable purposes. Likewise, a charity’s income from money it may hold in a bank account is not subject to tax. Charities may also receive dividends from any company shares they own free from income tax.

EXPLAINING THE LAW EXPLAINING THE LAW |

Have you ever been asked to ‘gift aid’ a donation to a charity? Gift aid enables a charity to reclaim basic rate tax that a taxpayer making the donation will have paid on their income.

For example, suppose Scott goes to a National Trust property and there is a ? entrance charge. He may be asked if he wishes to take advantage of the ‘gift aid’ scheme. It costs Scott no additional money. The entrance fee is then treated as a donation upon which the National Trust can reclaim the basic rate of tax (currently 20 per cent) that Scott will have been charged when he earned his salary. That means that the National Trust may reclaim a further 20 per cent (£1.25) from HM Revenue & Customs.

Charities enjoy other taxation exemptions and reliefs too. For example, the charity will not be charged capital gains tax (CGT) on any gains it makes, provided that the monetary gain is used for charitable purposes. When buying land, the charity will be able to purchase it free of stamp duty land tax (SDLT). If it has premises, the charity will pay lower business rates than a non-charitable organisation.

All of these reliefs and exemptions from taxation make charitable status attractive for an organisation or gift.

Legal advantages

Charities may exist under one of several different legal structures. For example, a charity may take the form of:

[a] A company limited by guarantee. This is where a limited company is formed to manage the charity and directors are appointed to run it. The company’s liability is limited by a guarantee provided by those individuals establishing it. No shares in the company are issued.

[b] An unincorporated association. This is a club or society where its members hold property on the basis of a contract between themselves (see Chapter 6 for further discussion).

[c] An express trust.

It is the concept of establishing a charity by an express trust that is of the most interest here and, generally, the discussion in this chapter will now proceed as though an express trust has been chosen as the medium to establish a charity.

As you know, express trusts have to be both declared and constituted.4 Charities are, however, allowed to deviate from several of the usual requirements needed to declare an express trust:

[a] To a certain extent, charitable trusts can deviate from the usual rules of certainty required when a trust is established.5 Usually there must be certainty of intention, subject matter and object when an express trust is established. Certainty of intention and certainty of object do not need to be complied with as rigidly in a charitable trust, because defined individuals are not intended to benefit from the trust: the trust is instead being established to benefit a purpose. Instead of specifying precisely who will benefit from the charitable trust, it is possible to state that the charity will exist for one or more of the general charitable purposes set out in s 3 of the Charities Act 2011.

Having said that, however, there are limits as to how far the rules of certainty can be disapplied, as shown in Chichester Diocesan Fund & Board of Finance (Incorporated) v Simpson.6

In his will, Caleb Diplock left his residuary estate (approximately £250,000) to ‘such charitable institution or institutions or any other charitable or benevolent object or objects in England’ as his executors should choose. The executors asked the court whether such a gift was valid as a charitable one or whether it was void for uncertainty. By a bare majority, the House of Lords held that it was void for uncertainty.

The key focus for the House of Lords was on the phrase ‘charitable or benevolent’. These words were seen by the majority to be disjunctive (not connected to each other). If necessary, the court could administer a trust for a charitable purpose, as the court could decide what a charitable purpose is in law. But the court could not administer a trust for a benevolent purpose. A benevolent purpose might be wider or narrower than a charitable purpose: it was impossible to say. By the use of the key word ‘or’ in his will, Mr Diplock had not demonstrated sufficient intention to benefit only a charitable object.

A different decision had been reached by the High Court in Re Best.7 The decision illus-trates how vital the use of the word ‘and’ can be instead of ‘or’. Thomas Best left his residuary estate to the Lord Mayor of Birmingham to be used for ‘charitable and benevolent’ purposes in the city of Birmingham and the wider counties in the Midlands. Farwell J held that the gift was a valid charitable gift. Mr Best had clearly stated an intention that his estate should only go to charities and he had simply limited those charities who could benefit by stating that they also had to have a benevolent purpose.

What is clear, therefore, is that certainty of intention must still be present in a charitable trust in that the settlor must show a clear intention to benefit a charity. The precise objects — as to which particular type of charity may benefit — may be dispensed with, as long as the court can construe an intention to benefit a charitable purpose as now defined in the Charities Act 2011;

[b] Generally speaking, English law discourages the use of purpose trusts.8 Yet charities are, by their very nature, examples of trusts established for a purpose as opposed to benefiting an individual. English law not only permits this, but actively encourages it, through the taxation reliefs and exemptions discussed. The rather cynical reason for this is that if the law stuck rigidly to its beliefs in that all trusts must benefit an individual, an increased burden would result on the government to take the place of providing all of the good works currently undertaken by charities which would result in an increased taxation burden to society in general;

[c] The beneficiary principle9 need not be met. Beneficiaries generally have a dual role: they not only enjoy the trust property but they also act as ‘enforcers’ of the trust against the trustee. They ensure the trustee administers the trust for their benefit and not his own. The beneficiary principle is, however, dispensed with in the case of a charitable trust. Bespoke enforcers of each charitable trust are not required because it is the Charity Commission’s role to take enforcement action10 against the charity trustees if they breach the terms of the trust; and

[d] Charitable trusts need not comply with the Rules against Perpetuity.11 Section 4 of the Perpetuity and Accumulations Act 2009 provides that the only perpetuity period permitted for trusts is a fixed period of 125 years. Broadly, this means that the property of the trust must vest in the beneficiaries within that time to prevent the trust being void. Charities do not suffer from such a requirement and may exist in perpetuity. For example, Thomas Barnardo started his work in 1867 and his charity still exists today.

The Charity Commission

The Charity Commission was formed by the Charities Act 2006.12 Prior to that Act, the Charity Commissioners13 had exercised the same roles as the Commission.

The Charity Commission has two main roles.14 The first is to keep a list of ‘registered’ charities. In doing this, it must decide whether charitable status can be granted to the organ-isation. The Charity Commission must base its decision on the definition of ‘charity’ in s 1 of the Charities Act 2011 and case law both prior to, and since, the enactment of that Act. The Charity Commission’s second function is to police charities. This means, to give just two examples, that it is responsible for ensuring that (a) a charity makes an annual return demonstrating its public benefit, and (b) that the trustees of the charity are administering the charity’s property correctly towards the aims of the charity and for the benefit of the public.

The Charity Commission’s two main functions are summarised in Figure 15.1.

Certain charities cannot have ‘registered’ status with the Charity Commission.15 These include those charities:

[a] with an annual income ofless than £5,000. Many local charities will fall into this category;

[b] known as ‘excepted’ charities providing that they have an annual income of £100,000 or less. Excepted charities are those which remain regulated by the Charity Commission but may not be registered unless their annual income exceeds £100,000. Excepted char-ities are so called because they are excepted from registration either by an order made by the Charity Commission or specific legislation. Such charities would, for instance, include Scout and Girl Guide groups; and

[c] known as ‘exempt’ charities. Exempt charities fall into two groups: those with a principal regulator and those without. Those with a principal regulator are regulated not by the Commission but by that regulator,16 which has usually been appointed by Parliament. Housing Associations often fall into this category.17 The regulator also ensures that the charity complies with its obligations under the Charities Act 2011 so there is no need for the Charity Commission to provide a second layer of regulation. Some exempt charities have no principal regulator,18 but these charities’ status is now being changed to ‘excepted’. This means that the Charity Commission will regulate all of this group but only those with an annual income exceeding £100,000 will have to register with the Charity Commission.

The Charity Commission will, therefore, regulate the vast majority of charities. In turn, the vast majority of charities will be registered.

On a day-to-day basis, however, it is the charity’s trustees who manage the trust property and administer the trust, just as in the case of any express trust. Under s 34(3)(a) of the Trustee Act 1925, there is no limit to the number of trustees of a charitable trust where the trust property includes land, unlike that of a non-charitable trust where the maximum number is limited to four.19

Definition of a Charity

Key Learning Point

There are three main requirements to be a charity in law:

(a) the trust must be for a charitable purpose;

(b) the trust must be for the public benefit, either as a whole or a sufficiently large section of it such that it can be seen to be benefiting the public; and

(c) the purposes of the trust must be wholly and exclusively charitable.

‘Charity’ in law is not defined in any popular sense. As Lord Simonds said in relation to its derived term ‘charitable’ in Chichester Diocesan Fund & Board of Finance (Incorporated) v Simpson,20 ‘it is a term of art with a technical meaning’. That ‘technical meaning’ is today to be found in s 1 of the Charities Act 2011, which provides that a charity:

[a] is established for charitable purposes only, and

[b] falls to be subject to the control of the High Court in the exercise of itsjurisdiction with respect to charities.

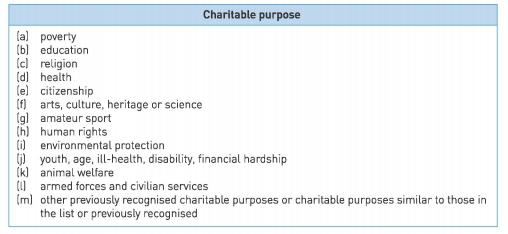

Section 2 states that a charitable purpose must be one falling within s 3(1) and be one which benefits the public. Section 3(1) sets out a list of 13 charitable purposes which are illustrated in Figure 15.2.

The Charities Act 2006 was not the first time that ‘charitable purpose’ was defined in law. The first recognition of what a charitable purpose could be was in the Preamble to the Statute of Charitable Uses 1601, but it was effectively the opinion of Lord Macnaghten in The Commissioners for Special Purposes of the Income Tax v Pemsel21 which provided a more modern definition of the phrase by summarising those charitable purposes under four main heads; this definition lasted until the Charities Act 2006.

The facts of the case concerned land left on trust in 1813 for the Moravian Church. One-half of the profits made from the land were instructed by the settlor to be used to maintain and support missionary work in other nations in order to convert people to Christianity. Relief from income tax for profits made from land owned for charitable purposes had been enacted under the Income Tax Act 1842.

Until 1886, the Inland Revenue had duly refunded income tax that the Church had paid on the profits it made from the land. In that year, however, the Revenue refused, claiming that the lands were not held on trust for ‘charitable purposes’. The Revenue’s view was that ‘charitable purposes’ revolved around how ‘charity’ would be defined in popular meaning which, in turn, meant solely the relief of poverty. That was the only sense in which most people would define ‘charity’. There was, the Revenue argued, no charitable purpose here as it was not necessarily the case that the money made from the land was to be used to relieve poverty.

By a majority, the House of Lords held that the phrase ‘charitable purpose’ was not restricted solely to the relief of poverty; instead the phrase had to be given its much wider legal meaning. The land was used for charitable purposes, so the relief from income tax should be reinstated by the Inland Revenue.

The case is known for the decision of Lord Macnaghten. He explained that the Court of Chancery:

has always regarded with peculiar favour those trusts of a public nature which, according to the doctrine of the Court derived from the piety of early times, are considered to be charitable.22

Later, the Statute of Charitable Uses 1601 was enacted to deal with abuses of charities. In order to do so, the Preamble to that Act had contained a definition of charitable purpose. This definition was ‘so varied and comprehensive that it became the practice of the court to refer to it as a sort of index or chart’.23 Successive courts viewed the list as a not exhaustive definition of what a charitable purpose could be; according to Lord Cranworth LC in University of London v Yarrow,>24 those charitable purposes in the Preamble were ‘not to be taken as the only objects of charity but are given as instances’. In turn, that meant that the courts saw purposes which were similar to those listed in the Preamble as deserving of charitable status. As Chitty J put it in Re Foveaux:25

Institutions whose objects are analogous to those mentioned in the statute are admitted to be charities; and, again, institutions which are analogous to those already admitted by reported decisions are held to be charities.

This approach effectively continues to this day as s 3(1)(m)(ii) of the Charities Act 2011 gives the court the ability to recognise as charitable anything which is either ‘analogous to, or within the spirit of’ any of the main charitable purposes listed in s 3(1) of the Act.

ANALYSING THE LAW ANALYSING THE LAW |

Think about the phrase ‘analogous to, or within the spirit of’ any of the main charitable

purposes listed in s 3(1) of the Charities Act 2011.

Suppose a celebrity chef opens a cookery school. He charges a fee for each participant to attend and learn from him. Could he claim that it is analogous to, or within the spirit of, the advancement of education and so claim charitable status for this activity?

Could the grower of a plantation of genetically modified crops claim that it is analagous to, or within the spirit of, advancing science?

It is questions such as these that the courts have had to wrestle with over centuries to decide whether to grant charitable status. These conundrums are set to continue due to the need to retain flexibility in the courts’ approach of being able to grant charitable status to purposes similar to those which already enjoy such status.

Lord Macnaghten set out his definition of the charity:

‘Charity’ in its legal sense comprises four principal divisions: trusts for the relief of poverty; trusts for the advancement of education; trusts for the advancement of religion; and trusts for other purposes beneficial to the community, not falling under any of the preceding heads.26

This definition was described by Wilberforce J in Re Hopkins’ Will Trusts as ‘the accepted classifica-tion into four groups of the miscellany found in the Statute of Elizabeth’.27

Lord Macnaghten’s summary of charity lasted until the Charities Act 2006 was enacted to consolidate the earlier Charities Act 1993 and other Acts relating to charity law. However, the first three heads of charity under s 3(1) of the Charities Act 2011 are practically the same as those enunciated by Lord Macnaghten. His final head has, arguably, been split up by the Act into the remaining ten heads listed in that subsection which perhaps give the definition of charity a more contemporary flavour. Those modern charitable purposes must now be examined.

EXPLAINING THE LAW EXPLAINING THE LAW |

The statutory definitions of ‘charity’ and ‘charitable purpose’ enacted for the first time in the 2006 Act were probably overdue. The Preamble was, by that stage, over 400 years old and its acknowledgement of charitable purposes reflected those prevalent in the time of Elizabeth I. The courts, by recognising further purposes as charitable by whether that new purpose was analogous to those listed in the Preamble, had created case law which was, at times, inconsistent. The new statutory definition of charity, including modern-day charitable purposes, was at least an attempt to bring charity law up-to-date and into the twenty-first century.

First Requirement of Charitable Status: There Must Be a Charitable Purpose

Each charitable purpose will be examined in the same order as it appears in s 3(1) of the Charities Act 2011.

The prevention or relief of poverty

The Preamble to the Statute of Charitable Uses 1601 referred to the relief of the aged, impotent (disabled) or poor.

In his opinion in The Commissioners for Special Purposes of the Income Tax v Pemsel, Lord Macnaghten showed that relieving poverty was essentially the only meaning the Victorians gave to charity. Lord Macnaghten argued persuasively that a charitable purpose could have other meanings, which he then defined.

Until the 2006 Act, this charitable head was concerned merely with relieving poverty. This head suggested any charity would have to demonstrate that it reacted to poverty by seeking to ameliorate it. The 2006 Act retained this definition, but also added to it by providing that charities under this head could, for the avoidance of doubt, act proactively. This charitable purpose would also include preventing poverty and not just relieving it. The 2011 Act retains this definition.

APPLYING THE LAW APPLYING THE LAW |

Do you think that the words of the 2006 Act changed this charitable purpose substantively? Is there, in practical terms, a great deal of difference between the prevention or relief of poverty? It is surely unlikely that the Charity Commissioners before the 2006 Act was enacted would have refused to register a charity which sought merely to prevent, as opposed to relieve, poverty.

In Attorney-General v Charity Commission for England and Wales,28 Warren J thought that there could, in theory, be a difference between preventing and relieving poverty. He gave the example of a charity providing money management advice as being one that could exist solely to prevent poverty. Yet, practically, in most cases charities will have objects that are for both the prevention and relief of poverty.

If a charity’s purpose must be the ‘prevention or relief’ of poverty, what is meant by ‘poverty’?

‘Poverty’ was defined by Evershed MR in Re Coulthurst.29 John Coulthurst declared a discretionary trust of £20,000 in his will and directed that his trustee should pay an allowance to any widows and orphaned children of either officers or ex-officers of Coutts & Co as the trustees thought were ‘most deserving of assistance’, according to their financial circumstances.

The Court of Appeal held that the trust was charitable, as it existed to relieve poverty. It did not matter that the trust did not precisely spell out that its objective was to relieve poverty. The court would look at the purpose of the trust as a whole and, if its aim was to relieve poverty, that would be sufficient to ensure that it could attain charitable status under this head. The decision may thus be seen as an application of the maxim that equity looks to the substance of the testator’s aim and not to the precise form of the words he chose to use.

Evershed MR went on to define ‘poverty’:

poverty does not mean destitution; it is a word of wide and somewhat indefinite import; it may not unfairly be paraphrased for present purposes as meaning persons who have to ‘go short’ in the ordinary acceptation of that term, due regard being had to their status in life, and so forth.30

The very nature of this trust suggested that its aim was to relieve poverty. It only benefited widows and orphaned children who were ‘most deserving of [financial] assistance’.

The notion that poverty is a relative concept may be shown by considering the facts of Re de Carteret.31

Here, the Right Reverend Frederick de Carteret, formerly the Bishop of Jamaica, declared a trust in his will of £7,000 which was to be invested and the income generated by it to be used to pay an annuity of £40 each to widows or spinsters living in England with a preference for those widows who had young dependent children. But the trust had a condition placed on it: to receive this annual sum, the widows or spinsters had to have an annual income of between £80 and £120. This level of minimum income meant, of course, that the potential recipients of the money were perhaps not poor by the standards of the 1930s. Again, the issue was whether such a trust could be valid as a charitable trust for, if not, it would be void as infringing the rules against perpetuity.

Maugham J held the trust was charitable. He stressed that poverty did not mean absolute destitution. A trust could be held to be charitable for the relief of poverty if its aim was to relieve people of limited means who were obliged to incur expenses as part of their ‘duties as citizens’.32 He said that, effectively, the widows had to have young dependent children to receive the annuity.

Whilst this decision affirms that poverty does not mean absolute destitution, it is suggested that it is, in some ways, a strange decision for the court to reach. Maugham J effectively reinterpreted the trust. The testator had placed a preference on widows with dependent children to benefit from the gift, but there was no compulsion on the trustees to distribute the money solely to these individuals. It may well be that the testator intended that widows without dependent children or spinsters could have benefited from his generosity. These two groups would not have had to incur the type of expenses in raising their children to which Maugham J referred as justifying his decision. His only way around this was to restrict the trust set up by the testator to widows with dependent children; it must be questioned whether restricting the testator’s trust truly reflected the testator’s wishes.

Whilst these decisions illustrate that the trust does not have to mention ‘poverty’ expressly to be considered charitable under this head, trusts are not usually charitable unless they are restricted to benefiting those who are poor. Where anyone can benefit from the trust, it will probably not be held to be charitable, as Re Sanders’ Will Trusts33 illustrates.

William Sanders created a discretionary trust over one-third of his residuary estate in his will so that his trustee could provide housing for the ‘working classes and their families’ who lived in the area of Pembroke Dock, Wales.

Harman J held that the trust was not charitable. It could not fall under this charitable head because it was not restricted to those people who were poor. As he put it, ‘[a]lthough a man might be a member of the working class and poor, the first does not at all connote the second’.34 ‘Working classes’ had no connection to the concept of poverty.

The decision could be distinguished from the earlier cases of Re de Carteret and Re Coulthurst. Both of those decisions concerned widows and/or orphaned children, where poverty could, apparently, be readily inferred. Mr Sanders’ trust was simply for the ‘working classes’, which were ‘merely men working in the docks and their families’.35

The decision in Re Sanders’ Will Trusts was, however, distinguished by Megarry V-C on not dissimilar facts in Re Niyazi’s Will Trusts.36

Mehmet Niyazi was originally a Turkish Cypriot. He left his £15,000 residuary estate on trust for the construction of a ‘working mens hostel’ (sic) in Famagusta, Cyprus. The issue was whether such trust could be charitable, considering the earlier decision of Harman J in Re Sanders’ Will Trusts.

Whilst acknowledging that the case was ‘desperately near the borderline’,37 Megarry V-C held that the trust was charitable. ‘Working men’ impliedly contained within its definition a reference to lower incomes. The use of the word ‘hostel’ was key to distinguishing the decision from Re Sanders’ Will Trusts. A hostel connoted a form of basic accommodation that only those who were poor would use, especially when prefixed by the phrase ‘working mens’. Re Sanders’ Will Trusts referred to ‘dwellings’ where those who were better off financially could live; the better off would be unlikely to benefit from the hostel in this trust.

Megarry V-C thought that he should take into account the comparatively small amount of money left by the testator for the project. Such a sum was unlikely to build the hostel by itself or, if it did, it would be a very modest one. In the latter case, only the poor would wish to live in it. Second, he thought that where a trust was to benefit a particular area, he should take the conditions in that area into account. He thought that:

a trust to erect a hostel in a slum or in an area of acute housing need may have to be construed differently from a trust to erect a hostel in an area of housing affluence or plenty. Where there is a grave housing shortage, it is plain that the poor are likely to suffer more than the prosperous …38

ANALYSING THE LAW ANALYSING THE LAW |

Re Sanders’ Will Trusts and Re Niyazis Will Trusts seem to give different decisions on what is meant by ‘working’ classes. Do you think the decisions can be reconciled? If so, how?

Charitable trusts for the relief of poverty used not to be required to show that they bene-fited either the public as a whole or a section of it.39 This was confirmed by the Court of Appeal in Re Scarisbrick.40 Neither is it a requirement that a charitable trust be perpetual in nature, even though the majority of them are.

Dame Bertha Scarisbrick left the remainder interest in half of her residuary estate (some £6,000) to be paid to her relatives who were in ‘needy circumstances’. The issue for the Court of Appeal was whether this could be construed as for the relief of poverty and thus be charitable. The difficulty with this phraseology was that it did not carry with it any objective standard of poverty and it did not limit the trustees to relieving the poverty of the relatives.

Evershed MR held that ‘needy circumstances’ could mean poverty. He pointed out that poverty was not an ‘absolute standard’41 and the recipients falling into such category had to be chosen. Those choosing had to do so honestly and the power of choice was a fiduciary discre-tion, so it had to be exercised in good faith.

Charitable status could be given even though it was the relatives of the testatrix whose poverty was being relieved. As will be discussed,42 public benefit must generally be demon-strated by a charity. A trust in favour of poor relations was an exception to this principle. Additionally, there was no requirement that the trust had to be perpetual in nature. Charitable trusts often were but if the trust fund was exhausted by making donations to those relatives in need, that did not mean to say that the trust was not charitable.

The issue of what is meant by relieving poverty needs to be addressed. Relieving poverty will, of course, often be undertaken by handing out monetary gifts, as demonstrated in a number of cases considered so far. Yet this is not the only way in which poverty can be relieved, as shown in Joseph Rowntree Memorial Trust Housing Association Ltd v Attorney-General.43

The claimant desired to build small flats or bungalows which it would then lease out to elderly people on a long lease in return for the person making a capital payment. Each resident would pay 70 per cent of the cost of the property; the remaining amount would be paid by a housing association grant. The properties were effectively what is known as ‘sheltered accommodation’ where a warden is also present to liaise with the elderly residents as and when required.

The Charity Commissioners argued that such a scheme was not charitable. They said that any benefits were provided by contract with the owners of the dwellings, not by way of outright gift, which was needed to relieve poverty and which gift could not be withdrawn, even if the people ceased to meet the qualifying criteria. Second, the scheme benefited private individuals as opposed to a class. Third, they also said that such a scheme could not be charitable, as it would result in the people making a profit on their dwellings as the amount of their investment rose with general property prices.

Peter Gibson J held that the scheme was charitable.

It was not necessary under the Preamble to the Statute of Charitable Uses that beneficiaries should have to prove that they were aged, impotent and poor. Those words had to be read disjunctively. It was enough that beneficiaries fell into one of those three categories. He defined ‘relief’ as meaning:

the persons in question have a need attributable to their condition as aged, impotent or poor persons which requires alleviating and which those persons could not alleviate, or would find difficulty in alleviating, themselves from their own resources.44

Peter Gibson J therefore considered that the need of the recipients had to have a causal connection to the generosity of the trust in order for their need to be relieved. On the facts, the recipients’ needs were due to their being elderly which could be relieved by the provision of housing accommodation. Such a trust could be considered charitable. The fact that the elderly people received their accommodation under a contract as opposed to pure gift was irrelevant to whether the trust could be charitable.

The scheme was for the benefit of a class of people: it was for the benefit of the class of people who were aged who had particular accommodation needs. Nor did it matter that the residents might receive a profit should the value of their properties increase: this was an inci-dental benefit to the charitable purpose as opposed to the main objective of the scheme. As such it was of no consequence. In addition, it was not as though the residents profited at the scheme’s expense.

Relief of poverty does not, therefore, entail simply handing out money to recipients. It can entail providing any relief to a condition caused by poverty.