Challenges Based on Bias and Predetermination

CHALLENGES BASED ON BIAS AND PREDETERMINATION

(2) Possible Grounds for Challenge Based on Bias or Predetermination | |

(1) The Principles of Bias and Predetermination

Actual and Apparent Bias

11.01 As explained in Chapter 10, an adjudicator is required to act in accordance with the principles of natural justice. That includes an obligation to act fairly and without bias.1 That obligation is reflected in s. 108(2)(e) of the Housing Grants Construction and Regeneration Act 1996 (‘the 1996 Act’) which provides that an adjudicator is required to be impartial.2 The Court of Appeal explained the concept of bias in In re Medicaments and Related Classes of Goods (No. 2) (2000):3

37. Bias is an attitude of mind which prevents the judge from making an objective determination of the issues that he has to resolve. A judge may be biased because he has reason to prefer one outcome of the case to another. He may be biased because he has reason to favour one party rather than another. He may be biased not in favour of one outcome of the dispute but because of a prejudice in favour of or against a particular witness which prevents an impartial assessment of the evidence of that witness. Bias can come in many forms. It may consist of irrational prejudice or it may arise from particular circumstances which, for logical reasons, predispose a judge towards a particular view of the evidence or issues before him.

11.02 There are two types of bias: actual and apparent. However, in practice, findings of actual bias are rare because of the difficulties of proof.4 Consequently, in order to resist enforcement of an adjudicator’s decision, it is more likely that a party will argue that the circumstances are such that there is a real possibility or appearance of bias. It is paramount that ‘justice should not only be done but should manifestly and undoubtedly be seen to be done’.5

The ‘Fair-minded and Informed Observer’ Test

11.03 The subjective impression formed by the aggrieved party is not enough to establish bias.6 The test for apparent bias was clarified in Medicaments:

86. … The court must first ascertain all the circumstances which have a bearing on the suggestion that the judge was biased. It must then ask whether those circumstances would lead a fair-minded and informed observer to conclude that there was a real possibility, or a real danger, the two being the same, that the tribunal was biased.

11.04 Medicaments was applied in the context of adjudication under the 1996 Act in Glencot Development and Design Co. Ltd v Ben Barrett & Son (Contractors) Ltd (2001) (Key Case)7 where particular consideration was given to the summary nature of the statutory procedure:

1. The adjudicator must conduct the proceedings in accordance with the rules of natural justice or as fairly as limitations imposed by Parliament permit.

2. Regardless of which adjudication rules applied, the concept of ‘impartiality’ in the Act must be given its usual meaning, which is the same meaning as at common law which entitles everyone to a fair hearing by an independent and impartial tribunal.

3. The test is an objective one: whether the circumstances would lead to a fair minded and informed observer, having considered the facts, to conclude that there was a real possibility, or a real danger, that the tribunal was biased.8

11.05 Medicaments was subsequently referred to by the Court of Appeal in AMEC Capital Projects Ltd v Whitefriars City Estates Ltd (2004) (Key Case)9 which confirmed that the ‘fair-minded and informed observer’ test applied to adjudication. In 2006, the House of Lords confirmed that this test was applicable when considering an allegation of apparent bias.10 In 2011 the Court of Appeal in Lanes Group Plc v Galliford Try Infrastructure Ltd (2011) (Key Case)11 discussed some of the difficulties in the application of this test:

51. One complication in recent years is the elaboration of the ‘fair minded observer’ test…. [T]he fair minded observer must be assumed to know all relevant publicly available facts. He or she must be assumed to be neither complacent nor unduly sensitive or suspicious. He or she must be assumed to be fairly perspicacious, because he or she is able ‘to distinguish between what is relevant and what is irrelevant, and when exercising his judgment to decide what weight should be given to the facts that are relevant’: see Gillies at paragraph 17.

52. There are conceptual difficulties in creating a fictional character, investing that character with an ever growing list of qualities and then speculating about how such a person would answer the question before the court. The obvious danger is that the judge will simply project onto that fictional character his or her personal opinions. Nevertheless, this approach is established by high authority …

11.06 There are myriad scenarios in which the apprehension of bias may arise and each case will be decided on its own facts and circumstances by applying the above test. The courts have confirmed that it would be dangerous or futile to attempt to exhaustively define each of the possible forms of bias in which there were real grounds for ‘doubting the ability of the judge to ignore extraneous considerations, prejudices and predilections and bring an objective judgment to bear on the issues before him’.12 However, it is useful to identify some of the scenarios in which a real danger of bias could arise:

1. Personal friendship or animosity between the tribunal and a member of the public involved in the case, particularly if the credibility of that individual could be significant in the decision of the case.13

2. Where a tribunal may have previously rejected the evidence of a particular person in such outspoken terms as to throw doubt on the tribunal’s ability to approach that person’s evidence with an open mind on any later occasion.14

3. If the tribunal had expressed views, particularly in the course of the proceedings, on a particular issue in such extreme and unbalanced terms as to throw doubt on his ability to try the issue with an objective judicial mind.15

11.07 While the guidelines and tests for establishing bias can be stated relatively simply, their successful application is more difficult and in most cases even apparent bias is difficult to prove. Following the decision of the Court of Appeal in AMEC v Whitefriars (2004) (Key Case),16 the party resisting enforcement has succeeded in only one of the 14 cases where apparent bias was raised as a ground for resisting enforcement.17 By comparison, in the period before AMEC v Whitefriars, enforcement was successfully challenged on the grounds of apparent bias in six of nine reported cases.18

Evidence from the Adjudicator

11.08 The explanation of the tribunal under review as to its knowledge or appreciation of the circumstances said to give rise to apparent bias is relevant and the fair-minded observer test should assess whether there was a possibility of bias in light of any such explanation.19 Evidence from the adjudicator has been considered in a number of cases.20 However, such evidence should only extend to a neutral factual account of the conduct of the adjudication; if the adjudicator goes any further, it could support the allegations of apparent bias.21

11.09 One TCC judge has suggested that it may be appropriate for the court to notify any adjudicator in the event that serious irregularity is asserted, in the same way as occurs with arbitration challenges.22 In Discain Project Services Ltd v Opecprime Development Ltd (No. 2) (2001),23 the adjudicator was called by the court rather than either party so that the parties would have the same opportunity to cross-examine him.

Bias and Natural Justice

11.10 In addition to the obligation to adopt a fair procedure, the adjudicator must also be free from bias or any reasonable perception of bias. As the Court of Appeal identified in AMEC Capital Projects Ltd v Whitefriars City Estates Ltd (2004) (Key Case),24 a fair procedure and bias are conceptually distinct:

14. … It is quite possible to have a decision from an unbiased tribunal which is unfair because the losing party was denied an effective opportunity of making representations. Conversely, it is possible for a tribunal to allow the losing party an effective opportunity to make representations, but be biased. In either event, the decision will be in breach of natural justice, and be liable to be quashed if susceptible to judicial review, or (in the world of private law) to be held to be invalid and unenforceable.

22. … It is only where the defendant has advanced a properly arguable objection based on apparent bias that he should be permitted to resist summary enforcement of the adjudicator’s award on that ground.

11.11 Notwithstanding the conceptual difference between natural justice and bias, a breach of natural justice may be such that it gives rise to an appearance of bias on the part of the adjudicator, in turn giving rise to parallel challenges on grounds of both a breach of natural justice and apparent bias.

Predetermination

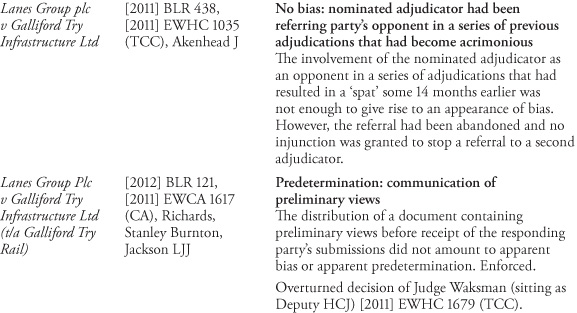

11.12 Predetermination arises when a judge or other decision-maker, in this instance, an adjudicator, reaches a final conclusion before being in possession of all the relevant evidence and arguments. In Lanes Group Plc v Galliford Try Infrastructure Ltd (2011),25 the Court of Appeal confirmed that predetermination is ‘conceptually somewhat different’ from bias, although it is often treated as a species of bias. The test of the fair-minded observer (outlined above at 11.03–11.05) is also applicable to allegations of apparent pre-determination by an adjudicator.26

(2) Possible Grounds for Challenge Based on Bias or Predetermination

Prior Connection with Parties or Matter

11.13 The Scheme does not say that an adjudicator shall be independent but paragraph 4 requires that a person requested or selected to act as an adjudicator shall not be an employee of any party to the dispute and shall declare ‘any interest, financial or otherwise, in any matter relating to the dispute’. This means that the appointment of an employee of either party will be an invalid appointment. Such an adjudicator will have no jurisdiction to decide the matter and any decision will not be enforceable. It is less clear what remedy is available to a party if the adjudicator validly selected and appointed by a nominating body declares an interest in the dispute that is objectionable to one party but still will not resign.

11.14 In Makers (UK) Ltd v London Borough of Camden (2008)27 one party suggested to RIBA to appoint a named adjudicator (because he was qualified as an architect and as a lawyer) and RIBA acceded to that requested. The challenge based on bias was rejected and the court found there was no duty to consult the other party where suggestions about nomination were made.

11.15 A claim of bias commonly arises where an adjudicator has been involved in a previous dispute concerning the project or the parties, including in some instances re-adjudication of exactly or essentially the same dispute following an earlier decision being held to be unenforceable. However, the mere fact that a tribunal has previously decided the issue is not of itself sufficient to justify a conclusion of apparent bias.28 As long as the circumstances are not such as to lead the fair-minded observer to conclude that the adjudicator approached the subsequent adjudication with a closed mind, then there will be no finding of bias. That will be so even if the same decision is reached, particularly if there are no different or further submissions or evidence. That the same decision is reached in such circumstances has been described as ‘entirely unsurprising’.29

11.16 Equally, the mere fact of a previous relationship or connection between the adjudicator and one of the parties or their representatives will not, without more, lead to a finding of bias. It will have to be shown that other circumstances exist, such as a personal rather than a professional relationship, that work provided by the party or its adviser accounts for a material proportion of the adjudicator’s practice or that the connection was such that the adjudicator had particular knowledge of the party that may be relevant to the dispute.30

11.17 In Lanes Group Plc v Galliford Try Infrastructure Ltd (2011)31 the adjudicator nominated by the ICE had previously acted against the referring party in a series of adjuications that had become acrimonious. The referring party considered that would make it difficult for the nominated adjudicator to appear impartial so did not make the referral but instead requested a further nomination. In hearing an application by the responding party for an injunction to prevent the referring party continuing the adjudication with the second nominated adjudicator, the judge found that the circumstances did not give rise to an appearance of bias. Further, the failure to pusue an adjudication following the nomination of an adjudicator and instead seeking the appointment of a different adjudicator was not a repudiation of the adjudication agreement and the adjudication by the second nominated adjudicator was allowed to continue.

11.18 The fact that an adjudicator has previously acted as dispute-resolver in proceedings involving one of the parties is also not, of itself, sufficient grounds to allege apparent bias or a lack of impartiality: Andrew Wallace Ltd v Jeff Noon (2008).32 In that case the adjudicator had been a mediator of an unrelated dispute with AWL only two days before being appointed as adjudicator by RIBA. The problem partly arose because when RIBA asked if the adjudicator had an existing relationship with either of the parties, the adjudicator said no. Whilst it could be said that the bias accusation might have been avoided had he made the disclosure before being appointed, the editors of the Building Law Reports have noted that the Court of Appeal in Taylor v Lawrence (2003)33 said that ‘judges should be circumspect about declaring the existence of a relationship where there is no real possibility of it being regarded by a fair-minded and informed observer as raising the possibility of bias’.34

11.19 Ultimately, the TCC Judge in Jeff Noon found the allegation of bias unsubstantiated and was led to this conclusion by the fact that the adjudicator: (i) had no personal knowledge of the parties; (ii) was a professionally qualified arbitrator; (iii) was appointed by RIBA as opposed to being a party appointee; and (iv) had no current relationship with either party.

11.20 If the adjudicator is in possession of relevant knowledge as a result of a relationship or prior adjudication, then unless that knowledge is made known to the other party there will be stronger grounds for a finding of bias. That was the case in Pring & St Hill Limited v C. J. Hafner (t/a Southern Erectors) (2002)35 where confidentiality requirements prevented the responding party being informed of the matters raised in the earlier adjudication, leading to a finding of apparent bias:

23. … In my view, in these circumstances, there is a very real risk that an adjudicator in [this adjudicator’s] position … would be carrying forward from an earlier adjudication not merely what he had seen or been told but also the judgments which he had formed, the opinions which he had reached, which led him to conclude that sum was the correct measure of McAlpine’s damages recoverable from PSH.

11.21 That same principle emerged in the subsequent case of London & Amsterdam Properties Ltd v Waterman City Estates Ltd (2003)36 (in which Pring was not cited) where one party unsuccessfully alleged relevant knowledge which the adjudicator denied. Judge Wilcox stated:

93. … Had he been in possession of relevant information which affected his decision, he was under a duty to tell the parties. If he was bound by confidentiality and unable to do so he should have recused himself.

94. A defendant seeking to impugn an adjudication cannot merely raise the spectre of bias without founding the allegation upon some credible evidence and demonstrating that the knowledge or information was central to the decision. In this case the Adjudicator addressed his mind to the risk, and stated that he knew of no matters giving rise to risk. His duty to guard against bias on this basis would have been a continuing one. There is no basis upon which it can be said that he was in breach of that obligation.

11.22 Such circumstances are likely to give rise to a parallel objection on the grounds of natural justice, the effect being that the adjudicator reached his decision in reliance on material that was not provided to a party.

Unilateral Communication

11.23 The court has given guidance that unilateral communication between the adjudicator and one party should be avoided but if it is considered absolutely necessary, it should be done in writing.37 The reason is plain: where there has been unilateral oral communication it is very likely to raise the suspicions of the other party as to the nature of the discussion and how it may have affected the mind of the adjudicator. However, such subjective concern is insufficient alone to resist enforcement. Where it is apparent that such discussions were of a purely administrative nature then there is unlikely to be a finding of apparent bias.38 However, where the substance of the dispute has been discussed between the adjudicator and just one party with the other party not being informed of the full detail of what was discussed and/or given an opportunity to make submissions in respect of the matters discussed, then it is more likely that apparent bias will be established.39

11.24 The same parallel natural justice objection as set out in relation to prior connections may also arise in such circumstances, but only if it is shown that information imparted during the unilateral communication materially affected the adjudicator’s decision.

Approach to Evidence

11.25 Attempts have been made to resist enforcement on the assertion that terms of the decision itself would lead the fair-minded observer to conclude that there was a real risk the adjudicator was biased. Such concerns have been based on the approach to or treatment of expert40 or factual41 witnesses or costs42 or the way the evidence has been used to support a conclusion.43 Such challenges have only succeeded in exceptional circumstances.

Access to ‘Without Prejudice’ Material

11.26 Parties have attempted to resist enforcement on the basis that there was apparent bias as a result of the adjudicator being provided with, or reference being made to, ‘without prejudice’ material. It is generally argued that there is a real risk that such material could be perceived to influence the adjudicator’s view of the merits of the position of the party that made the offer or otherwise asserted a position. Such a challenge is very unlikely to succeed where the adjudicator has been made aware of the mere fact of an offer having been made.44 Negotiations and offers prior to a referral to adjudication are not uncommon and probably the norm. An adjudicator will therefore generally expect there to have been negotiations and offers made and actual knowledge that is the case does not lead the informed fair-minded observer to consider that the adjudicator’s mind has been affected.45

11.27 Whilst the particular circumstances in the reported cases have not been sufficient to establish apparent bias, it would appear that it remains a possible ground for resisting enforcement. In Ellis Building Contractors Ltd v Vincent Goldstein (2011),46 following a review of the authorities, the judge commented, obiter, that ‘Where an adjudicator decides a case primarily upon the basis of wrongly received “without prejudice” material, his or her decision may well not be enforced.’ However, absent such clear influence on the decision, such challenges will be unlikely to succeed.

Predetermination

11.28 Bias towards or against a particular party could lead an adjudicator to predetermine a dispute. However, there may also be circumstances in which no bias exists but an adjudicator makes up his or her mind (or appears to do so) before all evidence or arguments are made and then fails to properly consider such submissions. There is a risk of such an allegation arising where, for example, an adjudicator issues a draft decision or ‘preliminary views’ document for consideration.47 Whilst taking such a step may be helpful to avoid allegations of breach of natural justice or excess of jurisdiction (by giving the parties an opportunity to make submissions on the points), an adjudicator must not reach a final decision prematurely:

56. There is nothing objectionable in a judge setting out his or her provisional view at an early stage of proceedings, so that the parties have an opportunity to correct any errors in the judge’s thinking or to concentrate on matters which appear to be influencing the judge. Of course, it is unacceptable if the judge reaches a final decision before he is in possession of all relevant evidence and arguments which the parties wish to put before him. There is, however, a clear distinction between (a) reaching a final decision prematurely and (b) reaching a provisional view which is disclosed for the assistance of the parties.