Asylum Seekers, Refugees, and the Politics of Access to Health Care: A UK Perspective

Asylum Seekers, Refugees, and the Politics of Access to Health Care: A UK Perspective

We must remember that the NHS is a national institution and not an international one … The aim of these proposals is to ensure that the NHS is first and foremost for the benefit of residents of this country.

John Hutton (former Minister for Health, 2004)1

It is the duty of a doctor … to be dedicated to providing competent medical service in full professional and moral independence, with compassion and respect for human dignity.

World Medical Association, Geneva Declaration 19482

Introduction

The UK government has recently consulted on proposals to exclude some ‘overseas visitors’, including asylum seekers, from NHS care.1 A judicial review took place at the high court in April 2008 regarding the rights of a failed asylum seeker to receive free hospital treatment in the UK.3 In this case the government’s policy of selectively prohibiting access to care was initially overturned although the government was successful in its appeal against this verdict.4 This chapter will examine the wider ethical, moral, and political issues that are raised by this debate.

Studies suggest that in almost all indices of physical, mental, and social wellbeing, asylum seekers and refugees suffer a disproportionate burden of morbidity.5–8 This population is already disempowered and restricted in access to services, and any further policy moves to limit access may therefore be unjust and exacerbate existing inequalities.

Many of the tensions at the heart of this debate provoke wider questions regarding the ethics of population health. How should we fund our healthcare system? Who should be entitled to care? Where and when should rationing be applied? How does society conduct this debate? These are some of the defining questions in the health inequalities arena. This paper will argue that this debate also raises far-reaching questions about the relationship between the NHS, society, government, and international governance.

Some Definitions

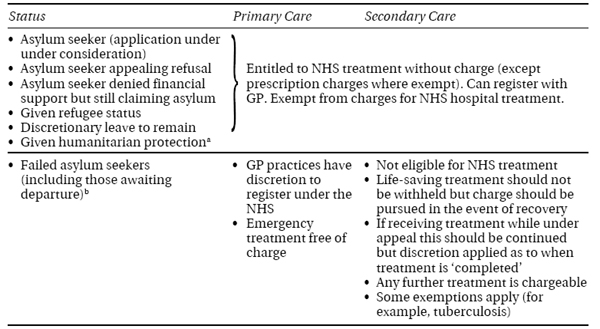

The term ‘refugee’ covers immigrants at all stages in the asylum process. Under the Geneva Convention, this includes any individual fearing persecution for reasons of race, religion, nationality, social, or political group, and who is consequently unwilling or unable to return to their home country.9 The UK categorises refugees according to the definitions outlined in Box 19.1.10

Box 19.1 Definitions of Refugee Status (Adapted from Burnett and Peel, 2001)10

- Asylum seeker: claim submitted (awaiting verdict).

- Refugee status: given leave to remain for 4 years and can then apply for indefinite leave. Restricted entitlement to family reunion.

- Indefinite leave to remain: indefinite residence. Restricted entitlement to family reunion.

- Exceptional leave to remain: right to remain for up to 4 years but expected to return to home country.

- Refusal: person has right of appeal within strict time limits and criteria.

The UK is a signatory to the European Convention on Human Rights, the United Nations Convention Against Torture, and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. These treaties oblige host countries to protect the most vulnerable people, offer ‘the highest attainable standard of health’, and specify not to limit equal access to health care.11

In some ways the Home Office application process is an attempt to homogenise an extremely diverse cohort. The demographic mix of the migrant population varies hugely, depending on the current geopolitical climate.12 Consequently, refugees’ health needs are diverse and they may differ as much from each other as they do from the domestic population. Nevertheless, there are several unifying themes that affect all migrant groups in terms of their physical, psychological, and social wellbeing.

The UK Asylum Process

Ultimately, decisions on immigration lie with the UK Home Office. By definition, demographic data for this population are difficult to collect. Numbers are possibly underestimated, as only those living in the country who have lodged an official application or appeal are included.13, 14

Pressure on migration is multifactorial and dependent on numerous host and recipient sociopolitical factors (including war, famine, and poverty).12 Recently, the most common nationalities seeking asylum have included Eritrean, Afghan, Iranian, Chinese, and Somali (countries where torture, war, anarchy, and other human rights abuses are commonplace). There is little evidence that migrants are specifically attracted by access to a higher standard of living or the welfare system.11, 15 Nevertheless, this remains a dominant perspective in some aspects of public debate.16

Asylum applications in the UK were at a peak of over 80,000 in 2002. Since then, this has reduced and remained at approximately 25,000 per year. The majority of applications tend to be unsuccessful. For example, of all applications lodged in 2006 only 10% were granted refugee status. Of those who were able to launch an appeal against this decision, 73% were dismissed.13

‘Failed’ asylum seekers are not necessarily ‘bogus’ asylum seekers, but have been unable to establish ‘to a reasonable degree of likelihood’ that they would suffer persecution if they were to return to their home nation. It is estimated that there may be as many as 450,000 failed asylum seekers remaining in the UK.17, 18

For individuals the process can be lengthy, bureaucratic, and confusing. At any one time an individual may be lodging an application, awaiting a decision, awaiting an appeal, or have been refused asylum. For some this can take several years.19 The length and complexity of this process has been criticised by the United Nations (UN), the House of Commons Home Affairs Committee, and several campaign groups.20 In comparison with its neighbours, the UK currently ranks 12th for number of asylum seekers per head of population.11

Health Issues Affecting Asylum Seekers

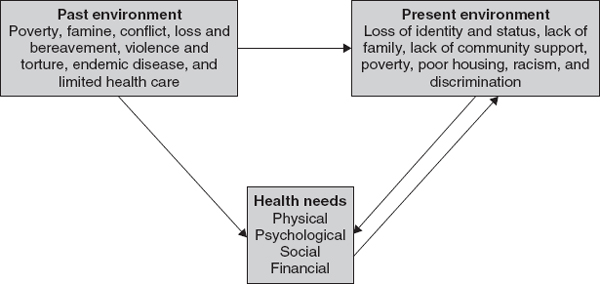

Health needs assessment data for UK asylum seekers are scarce.21 Evidence suggests that asylum seekers fare worse than the UK population on almost all measures of health and wellbeing. The health effects of the immigration process may be considered in terms of the past and present consequences of forced migration (Figure 19.1).

Figure 19.1 Model of health effects of forced migration and refugee status.

For this group, there is an unequal distribution not only of ill-health but also of the social determinants of ill-health (including poverty, social isolation, literacy, self-efficacy, and so on). It is generally agreed that there is a reciprocal relationship between ill-health and these wider determinants.22

This is a crucial point in considering how to reduce health inequalities, as it may not simply be a question of providing ‘more or better’ health care.23

Physical Health

Physical health needs of migrants tend to reflect the endemic spectrum of disease in their home country. Thus, infectious disease including HIV, tuberculosis, malaria, and other parasitic diseases are often more prevalent among immigrants from sub-Saharan Africa.5, 6 In many refugees from eastern Europe, higher rates of chronic disease, including diabetes and cardiovascular disease, have been reported.7

Other problems include poor dentition, malnutrition, and incomplete immunisation. In addition, health behaviour may be affected by forced migration. Several studies have reported a high prevalence of non-specific or somatising presentations as a result of psychosocial distress.8

Psychological Health

It is unsurprising that symptoms of depression, anxiety, and agoraphobia have been reported among refugees and asylum seekers.5 These symptoms may result from stressors including bereavement, displacement, or torture. Many of these symptoms are further exacerbated by conditions in the host country, including compulsory detention, poverty, unemployment, housing, and social isolation. Different cultures have different models for conceptualising mental health and seeking help, which may complicate the provision of services such as counselling.24

Although high rates of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) have been reported,25 much of the burden of illness may be beneath the level of formal psychiatric diagnosis.26 It is paradoxical, however, that those affected may only be able to seek help through a medical system that may stigmatise or label them. A diagnosis of PTSD may be sought in support of an asylum application. Some argue that the solutions to most psychological distress among refugees require social rather than medical intervention.8, 24

Financial Issues

Most asylum seekers and refugees are impoverished on arrival. Many may have specific skills and training that they are prevented from using in the UK, thus fostering a culture of dependence.27

Those who apply for asylum are subsequently entitled to benefits equivalent to approximately 70% of normal income support. This is dependent on remaining at a particular allocated accommodation. If an individual moves (which could be for reasons of seeking a social support network or because of racist abuse) or if their claim is refused, their benefits cease immediately, often leading to destitution.

Under the Immigration and Asylum Act 1999, most asylum seekers are not entitled to additional welfare benefits. As well as these theoretical restrictions, there are significant practical ones. For example, applicants on a low income can claim exemption from prescription charges if they complete an AG2 form. However, this is 16 pages long and available only in English. Therefore, there is a potential gap between entitlement to and provision of support.11

Social Issues

Social isolation is common among migrants as they may be separated from their family, friends, and functional role in society. The effects of this can be powerful. One study of Iraqi refugees in the UK suggested that depression was more strongly associated with social isolation than with a past history of torture.28 Many immigrants are deprived of the principles of respect, autonomy, and self-efficacy, which are increasingly thought of as contributing to positive health.29

Geographical Issues

Under the Immigration and Asylum Act 1999, many asylum seekers are relocated in areas with little experience of the needs of refugees. Some suggest that this may have worsened the problem of social isolation by actively discouraging integration.17, 21

Accommodation for asylum seekers is often in areas of existing deprivation, and they therefore inherit the same social determinants of ill-health as the native population, yet with additional barriers to care.

Detention is a particularly controversial topic, as there is increasing evidence that it leads to adverse mental health outcomes.30, 31 As well as prompting humanitarian concern, there is no evidence that this functions as a ‘deterrent’ to immigration. This might suggest that this policy is being pursued more as a political gesture.32

Women and Children

The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child recognises that children often suffer disproportionately as a result of government policy.33 Children face a double burden of lack of provision of current basic needs and future loss of opportunity through lack of education, socialisation, and normal development.34, 35

For women, there is the additional burden of child care and having to adapt to new roles and responsibilities. Women are more likely to report poor health and depression, yet in some cultures may be dependent on a man to disclose this. Women are often neglected in training and employment programmes. They are also more likely to suffer domestic violence and separation during periods of stress.36 Refugee women are also less likely to engage in screening, health promotion, family planning, and maternity services.7

There is a clear burden of need among this diverse population. At present the NHS barely meets these needs. Even if the government were to improve access and provision of services, many individuals would encounter other barriers that may be institutionally discriminatory. These include difficulties with literacy, cultural sensitivity, interpretation, confidentiality, and racism.37 For healthcare workers too, there is evidence of inadequate training, time, and resources to meet the needs of this group.38

Access to Care