Negotiation

Negotiation

19.1 NEGOTIATION STYLES AND STRATEGIES

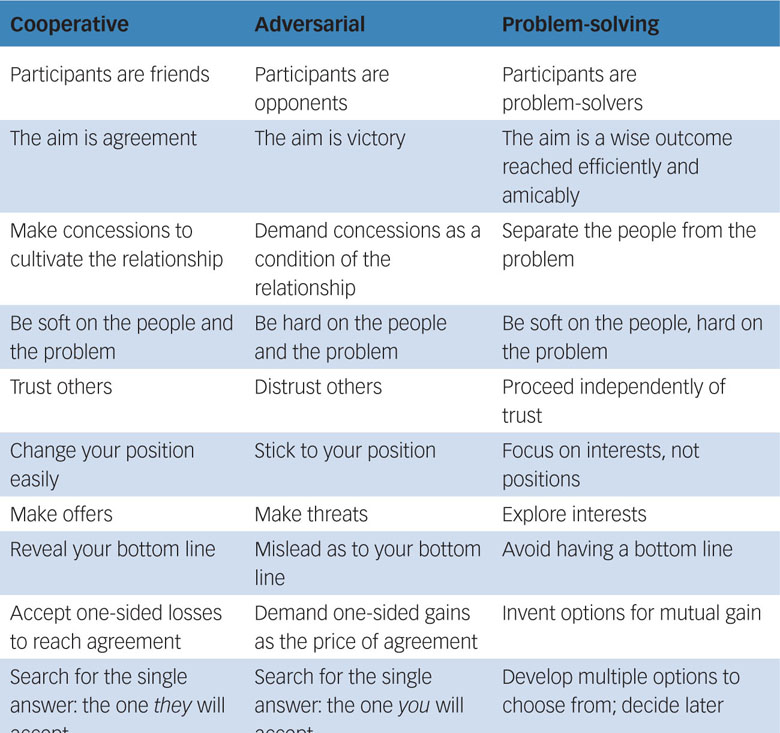

Negotiation style refers to the personal behaviour the negotiator uses to carry out the strategy that he/she has chosen. Three main styles of negotiation have been identified, and these are usually referred to as cooperative, adversarial and problem-solving.

Negotiation strategy refers to the specific goals to be achieved and the pattern of conduct that should improve the chances of achieving those goals.

Research has found that all effective negotiators have a number of features in common – they prepare on the facts, prepare on the law, take satisfaction in using their legal skills, are effective trial advocates and are self-controlled.

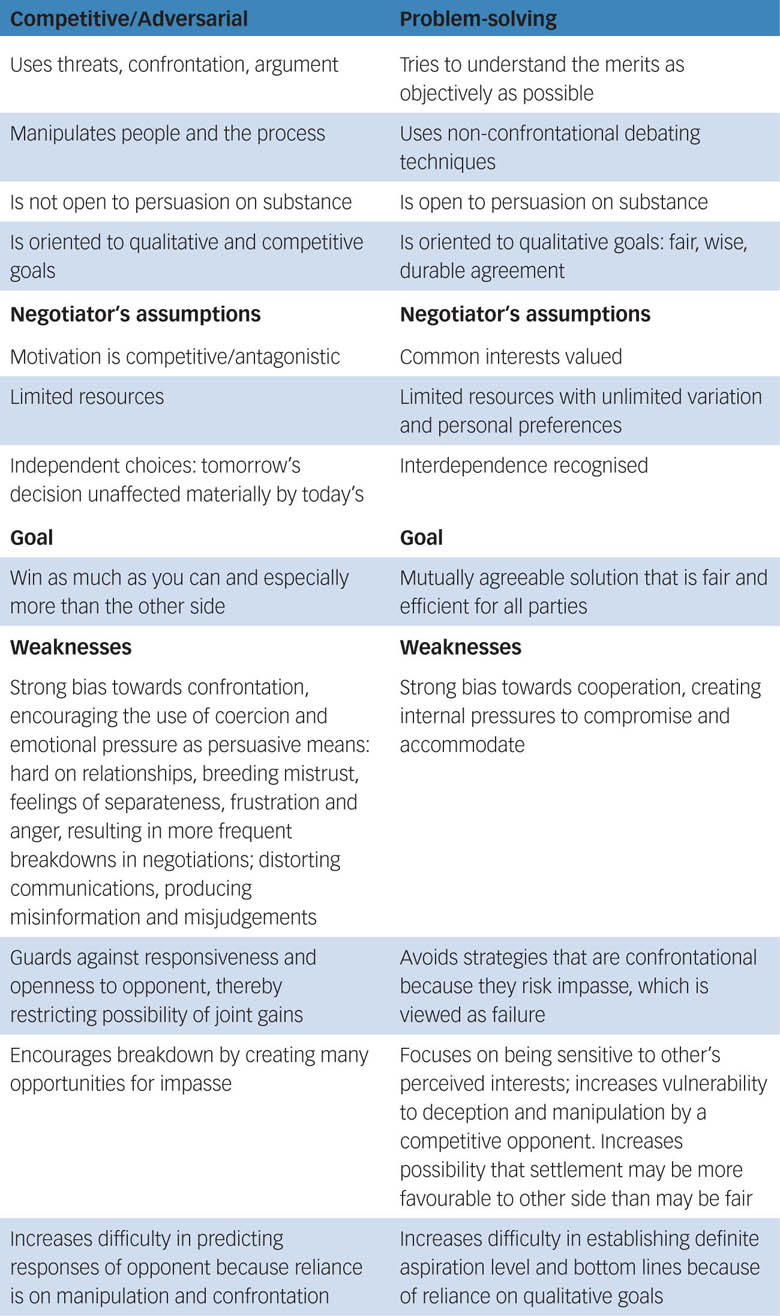

The main features of the three main styles of negotiation are summarised in the table below:

19.1.1 Adversarial/cooperative

Adversarial and cooperative styles of negotiation can be regarded as different forms of positional bargaining. In effect, both styles draw on the principle that the negotiators are opponents. The difference between them is the degree to which the cooperative negotiator is prepared to work with the other side in resolving the differences between them.

By contrast, the stereotypical adversarial negotiator is a tough and aggressive advocate whose aim is victory by defeating the opponent, in much the same manner as he or she might do in court.

19.1.2 Problem-solving

The problem-solving style can be characterised as a form of principled bargaining.

Problem-solving negotiators ‘separate the people from the problem’ and seek to negotiate in a non-confrontational and non-judgemental way, by applying standards of fairness and reasonableness.

Fisher and Murray summarise the essentials of this approach in their book, Getting to YES:

In most instances to ask a negotiator, ‘who’s winning’ is as inappropriate as to ask who’s winning a marriage. If you ask that question about your marriage, you have already lost the most important negotiation – the one about what kind of game to play, about the way you deal with each other and your shared and differing interests.

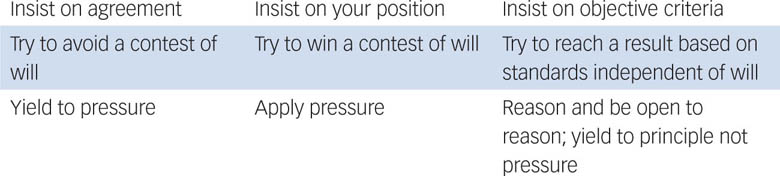

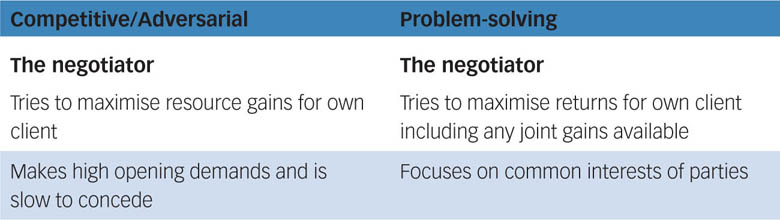

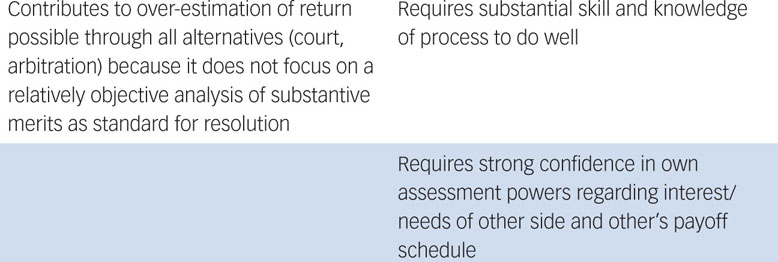

19.1.3 Negotiation strategies compared

The different negotiation strategies are compared in the table below:

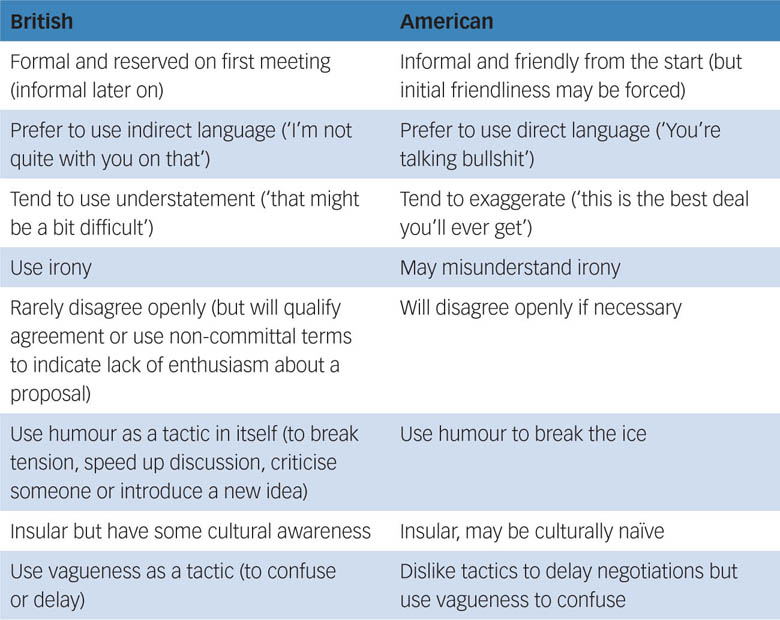

19.2 Differences in Negotiation Language Between Usa and Uk

In Chapter 9 we saw that there are certain differences between American and British English. These are relatively minor in comparison to the differences that exist in the mentality and cultural values of the two countries.

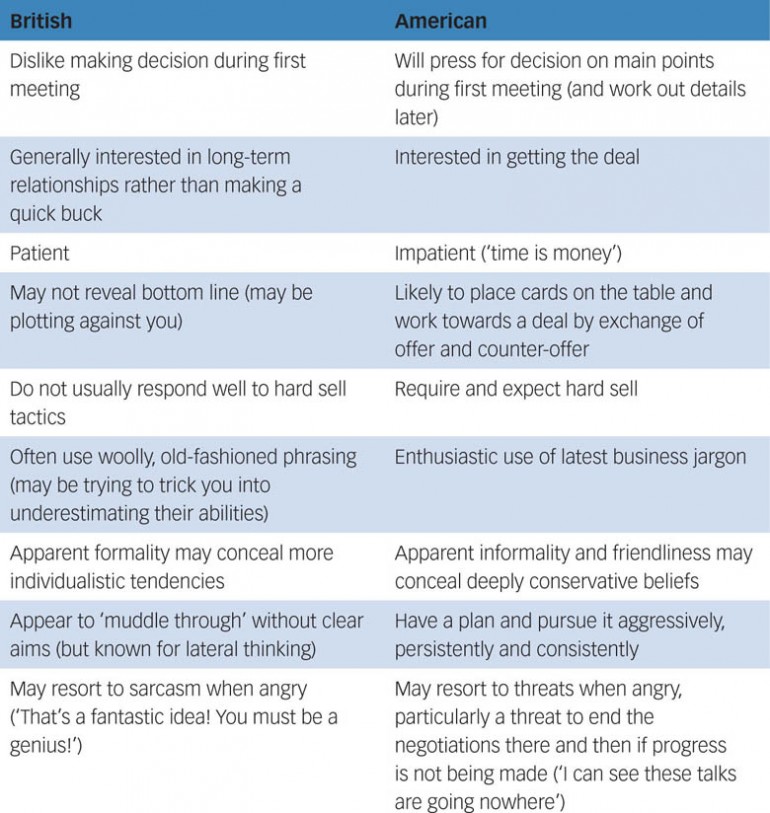

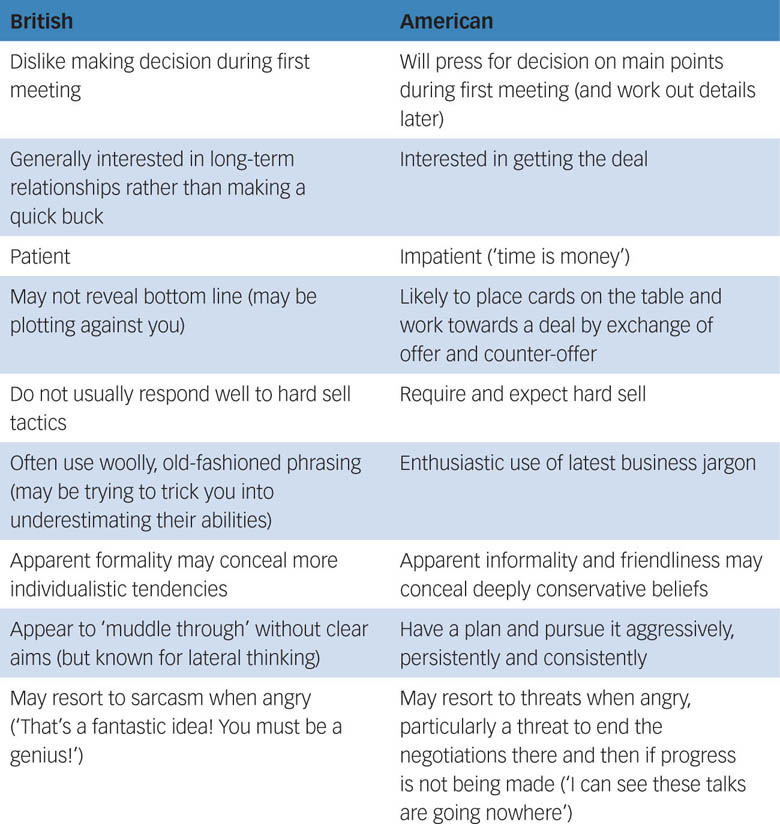

This table below briefly summarises how these differences affect the way American and British people use English in negotiations. Note that the USA and UK are selected here purely on the basis that they are the most prominent English-speaking countries. Differences also exist in the way in which other English-speaking countries, such as Australia, New Zealand, Canada and South Africa, use the language in negotiations.

British negotiators often like to present themselves as diplomatic amateurs. They often appear to ‘muddle through’ negotiations without any clear idea of what they wish to achieve. However, do not underestimate the British love of plotting (evidenced by the fact that one of Britain’s national heroes, Guy Fawkes, was a man who tried to blow up Parliament). Be aware that the woolly exterior may in fact conceal a considerable capacity for ruthlessness when needed. However, like American negotiators they rarely renege once a deal has been struck. The apparent disorganisation of some British negotiators is often viewed as a weak point by Americans and they may instinctively increase the aggressiveness of their approach when confronted with this style in order to ‘break’ their counterpart.

19.3 THE QUALITIES OF A GOOD NEGOTIATOR

Negotiation is the process of bargaining to reach a deal – but what does it actually involve? Does it mean being as tough as possible in order to get everything you want at that particular moment, or does it mean reaching a compromise that will preserve and even enhance a working relationship that will continue in the future?

The answer clearly depends on the kind of relationship you have, or want to have, with your opponent in the future. A good working relationship, like a good marriage, will probably involve neither of the parties getting everything they want, and both parties having to make concessions to the other.

So, what are the qualities that make a good negotiator? As a negotiator, you’ll find yourself in different settings, and dealing with different issues. However, there are three key skills that all negotiators need to develop:

1 an awareness of the need to live together after the talking has ended and life goes back to normal;

2 an anticipation of how people will be feeling and are likely to react;

3 the ability to conduct an ongoing ‘risk assessment’ as the negotiations progress.

In addition, it is often said that a good negotiator is one who:

• listens to what the other party is saying and observes their body language carefully;

• is able to assess changes in power between the parties;

• has the ability to persuade;

• is assertive where necessary (note that being assertive is not the same as being aggressive);

• has total commitment to the client’s case;

• is patient and remains cool under pressure;

• maintains self-control;

• knows the value to the client of each item to be negotiated – and, if possible, to the other side;

• is flexible, able to think laterally, and has imagination;

• avoids cornering the opponent unnecessarily, and avoids impasse;

• knows when to conclude – and when to push on;

• is realistic, rational and reasonable;

• is capable of self-evaluation;

• is able to put himself or herself in the other side’s shoes – but doesn’t stay there too long.

19.4 PREPARATION: FIVE-STEP PLAN

Preparing for negotiation is of crucial importance. The process of carrying out such preparation can be divided into five key steps, as follows.

19.4.1 Step 1: Research facts and law

Without a sound grasp of the facts and the applicable law, effective negotiation is impossible. Before the negotiation you should do the following:

• Review the case file.

• Consider the history and development of the case and identify the relevant facts.

• Identify the legal issues for each set of facts.

• Review agreements similar to those that will be the subject of the negotiation.

• Review the position of your opponents. How do they view the facts, what interpretations of the law favour their standpoint, what strengths and weaknesses are there in their case? You then need to prepare a balance sheet matching the strengths and weaknesses in each side’s case.

19.4.2 Step 2: Establish the client’s aims and agree strategy

You need to explore the full range of options that might be available to you, discuss these with your client, and then develop specific objectives for achieving these in the context of a particular negotiation.

The client needs to be advised that sticking at a certain point could lead to deadlock. A client who intends to adopt a cooperative strategy also needs to be warned that this could provide an opportunity for exploitation by the other side.

19.4.3 Step 3: Identify the client’s BATNA (Best Alternative to a Negotiated Agreement)

Negotiation is one of several means that might be used to achieve your client’s aims. The best test of any proposed joint agreement is whether it offers better value than any other solution outside of an agreement.

You should always seek to identify your client’s best alternative to a negotiated agreement (BATNA). Your client’s BATNA is the standard against which any proposed agreement is measured. Developing a BATNA protects your client from accepting terms that are too unfavourable and from rejecting terms that it would be in the client’s best interests to accept. It provides a realistic measure against which you can measure all offers.

Alternatives to an agreement might involve:

• Agreement with another party

• Unilateral action

• Mediation or arbitration

• Going to court

Working out a BATNA should provide you with a feel for what may be acceptable and what is not. To work out a BATNA you should construct a list of actions that your client might take if no agreement is reached, then select the option that seems best. You should then measure all proposed settlements against this alternative option.

19.4.4 Step 4: Decide what information you need to obtain

Information is continually exchanged during negotiations, and as this process occurs each party learns more and more about its opponent.

You should identify the following in advance of the meeting:

• The information that you need from the negotiation.

• The information that the other side is likely to protect.

• Any information that you want to give to the other side.

19.4.5 Step 5: Plan the agenda

An agenda should identify and illustrate the issues in dispute. It should distinguish three different dimensions of the negotiation:

• Content: the range of topics to be settled.

• Procedures: the manner in which the negotiation will take place, the control of the meetings, the matters to be discussed, the preliminaries, the timing of the different phases of the meeting.

19.5 19.5 THE NEGOTIATION PROCESS

19.5.1 Negotiation stages

Most negotiators have three basic positions in mind when carrying out negotiations. These are:

• The ideal position – what they would like to achieve in an ideal world.

• The realistic position – what they realistically expect to be possible.

• The fallback position. This is sometimes called the BATNA – which stands for ‘best alternative to a negotiated agreement’. In other words, what is the lowest offer the negotiator will accept and what other options does he or she have if the negotiation does not work out?

How does the process of negotiation work in practice? It is possible to break it down into five typical stages:

1 Preparation. This is crucial. The more you know about the subject-matter being negotiated, the other party’s interest, as well as your own, the quicker you will be able to adapt to new negotiating positions. In this way, you will be able to remain in control of the process throughout. We will look at this area in greater detail in a moment.

2 Opening moves. Your opening moves will largely involve investigating the issues and exploring the positions of both parties. You will need to express your views as well as actively listen to the views of others. It’s also worth drawing attention to any flaws in the other party’s position at this stage.

3 Offers. This is the stage where the most active negotiation occurs. As you receive and make offers, you may find yourself having to re-evaluate your position or re-package your ideas. You need to read the signals the other party is giving off quickly and accurately. Don’t be afraid to be creative.

4 Narrowing differences. Once the basic positions of each party have been established, and offers have been made, the process of narrowing the differences between the parties can begin. You will need to consider at this point the priority of the positions you have taken. What issues are you prepared to compromise on, and which not? What compromises do you require from the other party? What is the bottom line?

19.5.2 Conduct of the negotiation

The way in which the process of negotiation is handled will depend on the negotiation strategy each party is using.

A problem-solving negotiator will aim to identify mutual needs and produce solutions that satisfy both parties. He or she will seek to expand the options available to each party in a win/win negotiation.

An adversarial negotiator will try to maximise the gain to his or her client in a win/lose situation. He or she will seek the best for the client by denying options to the other side, and will only make concessions if absolutely necessary. The adversarial style can lead to deadlock and adversarial negotiators may have to switch to a more cooperative style towards the end of the negotiation.

19.5.2.1 Opening

Problem-solving negotiator. A problem-solving negotiator will aim to create an atmosphere that is cordial, collaborative but businesslike. He or she will start with some neutral non-business topic and will avoid sitting opposite the opponent – this can set up a face-to-face confrontation from the start. A problem-solver is likely to have prepared an outline agenda prepared and may start by seeking agreement with the other side about the procedure to be followed.

Adversarial negotiator. An adversarial negotiator is likely to keep the opening phases of the negotiation short and try to use it to project power and establish a psychologically dominant position. The negotiator will engage in initial ice-breaking, to establish a basis for communication, but will be brisk and businesslike. He or she will then move swiftly on to business, without discussing the procedures to be followed.

19.5.2.2 Exploring positions

Problem-solving negotiator