Land

Land

1.1 The Significance of Land

1. Land law deals with the legal relationship between land and the owner of that land.

2. Many different persons can have competing claims to different interests in respect of the same piece of land.

3. The interests of owners of neighbouring land often affect the rights of a landowner, so land should not be seen in isolation.

4. This becomes more significant as more land is taken into residential ownership.

5. Ownership of land therefore comprises not only rights one may have over one’s own land, but also rights one may have over a neighbour’s land, either to use their land in a particular way or to prevent a particular use they may wish to make of the land.

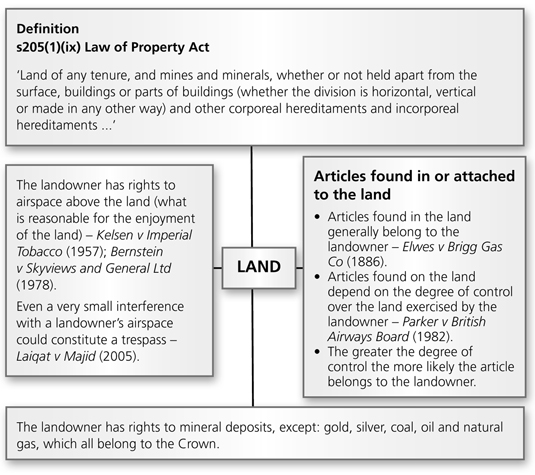

1.2 The Definition of Land

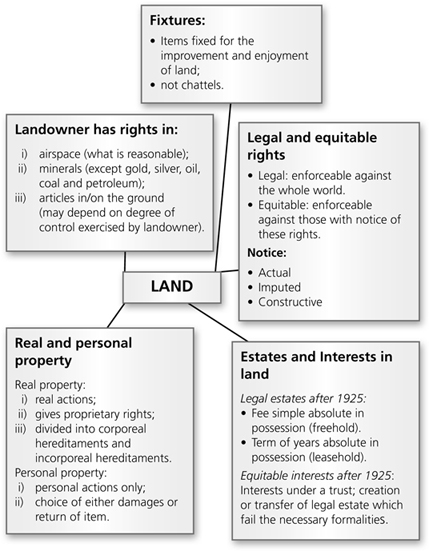

1.3 Real and Personal Property

1. Property is divided into real and personal property.

2. Real property mainly comprises land and is property that can be recovered by a real action, allowing the claimant to recover the property itself.

3. Personal property is property that can only be recovered by a personal action, allowing the defendant a choice between returning the item or paying a sum in damages.

4. Historically, leaseholds were treated as personal property and could only be recovered by personal action, i.e. the claimant might have to be satisfied with damages only.

5. Today the important issue is whether a right over land is personal or proprietary.

6. A proprietary right is a right in the land itself which will even bind a third party purchaser.

7. A lease is now defined as a proprietary right in land.

8. A personal right is a right against another person and cannot bind a third party, e.g. a bare licence only gives someone the right to remain on the land until the licence is revoked by the licensor.

1.3.1 Real Property

1. Under the Law of Property Act 1925 s 1(1) there are only two legal estates in land, leasehold and freehold.

2. An estate in land can also be called real property.

3. Land includes rights called incorporeal and corporeal hereditaments.

4. Hereditaments are rights that can be inherited and so can pass under a will or an intestacy.

5. Corporeal hereditaments are physical objects, e.g. land and anything attached to it, such as buildings, trees and minerals. Incorporeal hereditaments are rights in land that are not physical things, e.g. easements and profits, but can be very valuable.

1.4 Legal and Equitable Rights

1. Historically:

legal rights were enforceable only in the common law courts of the King;

legal rights were enforceable only in the common law courts of the King;

equitable rights were enforceable by the King’s Chancellor in the Court of Chancery, but only at his discretion.

equitable rights were enforceable by the King’s Chancellor in the Court of Chancery, but only at his discretion.

2. Today, legal rights are distinguished from equitable rights in land because only the owner of a legal estate can deal with the estate at law, and the owner of the equitable estate merely has rights in equity.

3. Although he/she may be able to claim the right to be consulted before the legal estate is sold.

4. In certain circumstances the purchaser may take the estate subject to an equitable estate.

5. Apart from the two legal estates arising under s1(1) LPA 1925 there are lesser interests that are enforceable at law, called legal interests, which are listed under s1(2) LPA 1925, e.g. easements, rentcharges and legal mortgages.

6. Any right that can exist ‘at law’ may give rise to a legal right, but only if certain statutory requirements are met, e.g. legal rights in land must generally be created and conveyed by deed: LPA 1925 s52(1).

7. Any right that does not qualify as a right in law must necessarily exist in equity: LPA 1925 s1(3):

interests of a beneficiary under a trust – the trustee owns the legal estate and the beneficiary owns the equitable estate;

interests of a beneficiary under a trust – the trustee owns the legal estate and the beneficiary owns the equitable estate;

interests under contract to create legal estates or interests – the purchaser is treated as owning an equitable estate from the date the contracts are exchanged;

interests under contract to create legal estates or interests – the purchaser is treated as owning an equitable estate from the date the contracts are exchanged;