Dworkin

Dworkin

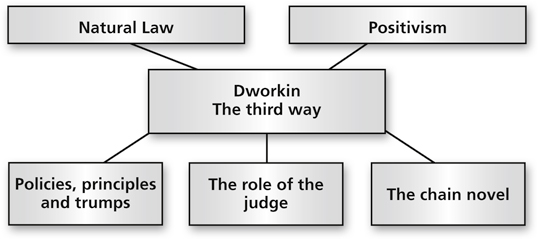

10.1 The Third way

1. Ronald Dworkin (b. 1931) is discussed here in light of the various movements previously addressed and particularly because he takes what is sometimes described as a third way or position between natural law and legal positivism, his response in Law’s Empire (1986) to Hart’s version of positivism.

2. He does not accept natural law notions of pervading moral norms required to shape the law and that expect law to be analogous to justice, although he does accept that moral principles are relevant to law when they are actually applied by judges.

3. Whilst agreeing that there are legal rules to guide behaviour, he nevertheless rejects those premises of legal positivism that limit judgements of what law is about and that require complete separation of law and morality.

4. Austin’s sanctions, Kelsen’s norms and Hart’s rules of recognition are all substantial but only partial approaches to understanding what can be considered as law.

5. In order fully to appreciate the essential nature of law there is a need to go beyond Hart’s rules and consider policies and principles as well.

6. Rules and principles differ:

(a) rules either apply to a particular situation or they don’t

(b) principles are broader and more flexible

(c) these are tools that allow the right conclusion to be reached even in uncertain situations where an obvious answer is not apparent.

7. Conflicting principles have to be weighed one against another to determine in particular circumstances which of them should prevail.

8. Hence the rule of law that would allow a son to inherit from his parent, even if he had murdered that parent, has to be overborne by the overriding principle that prevents criminals benefiting from their crimes.

9. Dworkin’s writings can be recognised as having three phases:

(a) initially he addressed Hart’s contention that law comprises a set of rules which judges can use to reach decisions, but ignoring matters such as policies and principles that were not rule-based

(b) he made further inroads into legal positivism by inventing a device in the form of the all-knowing judge, Hercules, to deal with hard cases, and who is able to reach the just and right judgment however difficult the case or obscure the underlying law

(c) in Law’s Empire and later work the notion of constructive interpretation is developed, the interpretivist theory being that legal rights and duties are determined by a community’s best interpretation of political practice, which has two aspects: