TRIPS Provisions as Interpreted by the WTO Dispute Settlement Organs

7

TRIPS Provisions as Interpreted by the WTO Dispute Settlement Organs

THIS CHAPTER EXAMINES how the WTO dispute settlement organs have interpreted TRIPS provisions. Except for the initial period following the establishment of the WTO, there have been few dispute cases over the TRIPS provisions: only three cases have been appealed. Nonetheless, the reports on these disputes are important guideposts for interpreting TRIPS, especially about the objective and principles of the Agreement, its exceptions and limitations, non-discrimination principles and TRIPS ‘flexibility’ as understood by the WTO dispute organs. The WTO dispute organs emphasised the importance of the customary rules of international public law in interpreting the TRIPS Agreement, as has been the case for all the WTO-covered agreements, and, in particular, the wording of the treaty provisions to be interpreted. This may be due largely to Article 3.2 of the Understanding on Rules and Procedures Governing the Settlement of Disputes (DSU), which defines the role of the WTO dispute settlement system. According to Article 3.2 of the DSU, this system serves ‘to preserve the rights and obligations of Members under the covered agreements, to clarify the existing provisions of those agreements in accordance with customary rules of interpretation of public international law’, but cannot add to or diminish the rights and obligations provided in the covered agreements. This disciplined approach to interpreting TRIPS provisions seems to have prevented potential political arguments based on limited market data.

I AN OVERVIEW

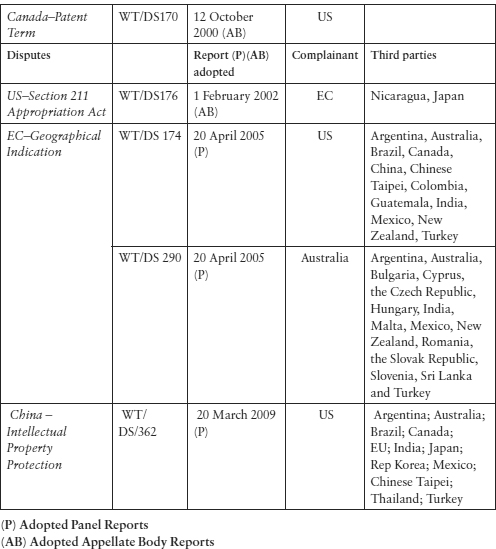

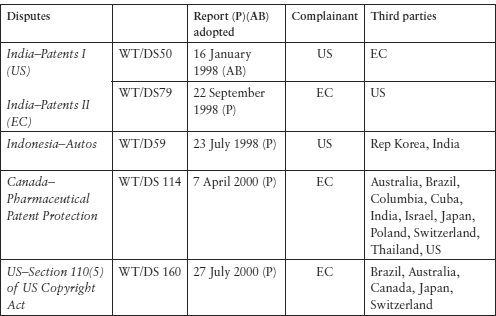

From 1 January 1995 to 30 September 2009, there were a total of 399 requests for consultations and 122 Panel and Appellate Body Reports.1 Of these, only 13 Panel and Appellate Body Reports concerning the TRIPS Agreement were adopted, in a total of eight cases. The findings of Panel Reports are binding only on the parties to the dispute, and although the Appellate Body reports can have a wider impact on legal, systemic questions, there are to date only three Appellate Body reports concerning this Agreement.

WTO Disputes relating to the TRIPS Agreement

Table 7.1: Disputes where a Panel report (P), or Panel and Appellate Body (AB) Reports are adopted

Table 7.2 Cases where consultations have been initiated (pending)

Table 7.3: Settled disputes

Disputes | Complainant | Notification of Mutually Agreed Solution |

Portugal–Patent Protection under the Industrial Property Act (WT/DS37) | US | 3 October 1996 |

Japan–Measures Concerning Sound Recordings (WT/DS28, WT/DS42) | US EC | 24 January 1997 (US) |

Pakistan–Patent Protection for Pharmaceutical and Agricultural Chemical Products (WT/DS36) | US | 28 February 1997 |

Denmark, Sweden–Measures Affecting the Enforcement of Intellectual Property Rights (WT/DS83, WT/DS86) | US | 2 December 1998 (S) |

Ireland–Measures Affecting the Grant of Copyright and Neighbouring Rights (WT/DS82) | US | 6 November 2000 |

EC–Measures Affecting the Grant of Copyright and Neighbouring Rights (WT/DS115) | US | 6 November 2000 |

EC–Enforcement of Intellectual Property Rights for Motion Pictures and Television Programs (WT/DS124) | US | 20 March 2001 |

Greece–Enforcement of Intellectual Property Rights for Motion Pictures and Television Programs (WT/DS125) | US | 20 March 2001 |

Brazil–Measures Affecting Patent Protection (WT/DSDS199) | US | 5 July 2001 |

Argentina–Patent Protection for Pharmaceuticals and Test Data Protection for Agricultural Chemical Products (WT/DS171) | US | 31 May 2002 |

Argentina–Certain Measures on the Protection of Patents and Test Data (WT/DS196) | US | 31 May 2002 |

China–Measures Affecting Financial Information Services and Foreign Financial Information Suppliers(WT/DS372) | EC | 4 December 2008 |

Table 7.4: Disputes where consultations continue (inactive)

Disputes | Complainant | Respondent |

EC–Patent Protection for Pharmaceutical and Agricultural Chemical Products (WT/DS153) | Canada | EC |

US–Section 337 of the Tariff Act of 1930 and Amendments thereto (WT/DS/186) | EC | US |

US–US Patents Code (WT/DS/224) | Brazil | US |

TRIPS interpretation has so far relied much on finding the ordinary meaning of the terms in the Agreement, often supported by the effectiveness principle (ut res magis valeat quam pereat). Additionally, Panels and the Appellate Body have relied extensively on the provisions in the Paris and Berne Conventions, and their related documents, guidelines and preparatory work, as ‘context’, ‘contextual guidance’ or ‘extended context’ for the purpose of interpreting the TRIPS Agreement. From the previous GATT system, there has been some interpretative guidance for TRIPS dispute cases, but mainly on the issues of national treatment and most-favoured nation principles.

The text of the TRIPS Agreement is brief, and little preparatory work is available. During the Uruguay Round negotiations, the Secretariat Notes and various written proposals from participants were available, but there was no drafting committee to keep track of the processes by which the text of the TRIPS Agreement was adopted. There was no accumulation of experience within the GATT regarding intellectual property rights (IPRs).

When the meaning of a treaty provision is sufficiently clear, no interpretative guidance is sought from the Vienna Convention. In such cases, Panels and the Appellate Body have relied directly on the wording of the Agreement, including its titles and footnotes. In searching for the meaning of ‘rights holders’ to whom civil judicial procedures should be made available by the WTO Members, the Appellate Body in US–Section 211 Appropriation Act4 simply relied on the footnote to Article 42 TRIPS, which states that: ‘For the purpose of this Part [III], the term “right holder” includes federations and associations having legal standing to assert such rights’.5 Under the TRIPS Agreement, therefore, procedures should be available not only to those who obtain IPRs, but also to any party which has legal standing to assert such rights. Footnotes were also examined to determine the meaning of ‘nationals’ of the customs territory (footnote 1 to Article 1.3 TRIPS – see chapter 5),6 and whether principles of national treatment apply to the use of IPRs generally, or if they only apply to ‘those matters affecting the use of IPRs specifically addressed in the TRIPS’ (footnote to Article 3.1).7 The Panel and the Appellate Body, in dealing with TRIPS cases, have referred also to GATT Panel Reports and the 1994 GATT.8 In EC–Geographical Indications,9 the Panel referred to the GATT report on US–Section 337,10 as well as the Panel and Appellate Body reports in US–Section 211 Appropriation Act, and stated that national treatment relates to ‘effective equality of opportunities’ of the nationals of Members with regard to the protection of IPRs, to the nationals of the Member concerned.11

When the examination of ‘preparatory work’ for the elaboration of the TRIPS Agreement was needed, the text, guidelines and model laws relating to the relevant provisions of the Paris or Berne Conventions were often referred to as ‘contextual guidance’ or ‘contextual support’. In examining the historical context of TRIPS provisions in terms of previous IP treaties, the Appellate Body in US–Section 211 Appropriation Act stated that Article 6 quinquies of the Paris Convention offered ‘contextual support’.12 These concepts relating to ‘context’ in interpreting TRIPS do not necessarily derive from Article 31 VCLT.

II TRIPS INTERPRETED BY WTO DISPUTE ORGANS

A ‘Context’ for the purpose of Interpreting TRIPS

Article 2 TRIPS concerning ‘intellectual property conventions’ stipulates in para 1 that ‘[i]n respect of Parts II, III and IV of this Agreement, Members shall comply with Articles 1 through 12, and Article 19 of the Paris Convention (1967)’, while Article 9 concerning ‘Relation to the Berne Convention’ provides that ‘Members shall comply with Articles 1 through 21 of the Berne Convention (1971) and the Appendix thereto’.13

The Panel in US–Section 110(5) Copyright Act20 analysed also the extent to which the minor exceptions doctrine forms part of the Berne Convention acquis and whether this principle has been incorporated into the TRIPS Agreement, by virtue of Article 9.1 TRIPS, together with Articles 1–21 of the Berne Convention (1971). For determining whether this doctrine, which primarily concerns de minimis use for the Panel, is part of the Berne Convention and the TRIPS Agreement, or forms a ‘context’ within the meaning of Article 31 VCLT, the Panel explored the intention of the parties21 as reflected in the wording of relevant documents. The Panel found that the minor exceptions doctrine forms part of the ‘context’ within the meaning of Article 31.2(a) of the Vienna Convention, of at least Articles 11 and 11 bis of the Berne Convention (1971).22 The Panel then looked into the preparatory work, notably in the documents of the TRIPS Negotiating Group, which confirmed that the information concerning this doctrine was provided by the International Bureau of WIPO,23and that no record exists of any party challenging the idea that the minor exceptions doctrine is part of the Berne acquis on which the TRIPS Agreement was to be built. From this, the Panel concluded that, in the absence of any express exclusion in Article 9.1 of the TRIPS Agreement, the incorporation of Articles 11 and 11 bis of the Berne Convention (1971) into the Agreement included the entire acquis of these provisions, including the possibility of providing minor exceptions to respective exclusive rights.24 Although it is not exactly reflected in the language of Article 9.1 TRIPS, the Panel concluded that ‘if that incorporation should have covered only the text of Articles 1–21 of the Berne Convention (1971), but not the entire Berne acquis relating to these Articles, Article 9.1 of the TRIPS Agreement would have explicitly so provided.’25

The Panel relied not only on various kinds of ‘context’ for treaty interpretation, but on a ‘general principle of interpretation’ to establish the legal status of the minor exceptions doctrine. According to the Panel, in the area of copyright, the Berne Convention and the TRIPS Agreement form ‘the overall framework for multilateral protection’. Furthermore, most WTO Members are also parties to the Berne Convention. For the Panel, adopting a meaning that would reconcile the texts of different treaties and avoid conflict between them, is a general principle of interpretation, based on public international law’s presumption against conflicts.26 The Panel did not recognise either Article 10(2) of the 1996 WIPO Copyright Treaty (WCT – see chapter 2), as a subsequent treaty on the same subject matter within the meaning of Article 30 VCLT27, or subsequent agreements on the interpretation of a treaty within the meaning of Article 31.2(b) VCLT, or subsequent practice within the meaning of Article 31.3 VCLT. However, as all 127 signatories to the TRIPS Agreement in the WTO took part in all of the WCT meetings, the Panel held that it is also relevant to seek ‘contextual guidance’ in the WCT when developing interpretations that avoid conflicts within the overall framework of multilateral copyright protection, except where these treaties explicitly contain different obligations.28 The Panel concluded, therefore, that the TRIPS Agreement and the WCT should be interpreted consistently with each other.29

In an attempt to identify the scope and the level of protection provided by TRIPS provisions incorporating previous IPR treaties, the WTO Panels and the Appellate Body have resorted thus to different kinds of treaty ‘context’, which are not necessarily within the meaning of Article 31 VCLT. In Canada–Pharmaceutical Patents,30 the Panel considered that Article 9(2)31 of the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works (1971) is a ‘rule of international law which the interpreter must consider, together with the context’ which falls under Article 31.3(c) of the VCLT, and referred to it as ‘an important contextual element for the interpretation of Article 30 of the TRIPS Agreement’, calling this provision ‘extended context’.32

The analysis of the ‘context’ for the purpose of interpretation based on the VCLT rule, determines important questions such as whether the scope of exceptions and the level of protection differs between the Berne Convention and the TRIPS Agreement based on Article 13.

The main difference between Article 9(2) of the Berne Convention (1971) and Article 13 of the TRIPS Agreement is that the former applies only to the reproduction right, whereas Article 13 does not contain an express limitation in terms of the categories of rights under copyright to which it may apply.33

The EC (today the European Union) argued that the provisions of Article 13 of the TRIPS Agreement and those of Article 11(1)(ii) and Article 11 bis of the Berne Convention provided different standards. The EC contended that parties to the Berne Convention could not agree that another treaty (ie the TRIPS Agreement) reduces the Berne Convention’s level of protection. From the wording or the context of Article 13 of the TRIPS Agreement, according to the EC, the Berne acquis could not be considered to be incorporated in the TRIPS Agreement. The EC contended therefore that Article 13 applied only to the rights newly adopted under the TRIPS Agreement.34 The US argued that the TRIPS Agreement incorporates the substantive provisions of the Berne Convention (1971), and that Article 13 TRIPS provides the standard by which to judge the appropriateness of limitations or exceptions, with which s 110(5) is compliant. According to the Panel, Article 11 bis(2)35 of the Berne Convention (1971) and Article 13 TRIPS cover different situations.36

Reports of successive revision conferences of the Berne Convention refer to ‘implied exceptions’ allowing Member countries to provide limitations and exceptions to certain rights. The so-called ‘minor exceptions’ doctrine concerns those minor exceptions to the right of public performance, a concept which is close to the notion of ‘fair use’.37 The doctrine is not explicitly described in terms of exceptions in the Berne Convention, which refers to the conditions allowing national laws to provide for exceptions, using a three-step test, with respect to Articles 11 and 11 bis, and other exclusive rights (such as the right of translation) of the Berne Convention. The three-step test is a standard by which limitations on exclusive copyrights are confined to ‘certain special cases’ which do not conflict with ‘normal exploitation of the work’, do not ‘unreasonably prejudice the legitimate interests of the author’, and are applied to the right of reproduction.38

Article 13 of the TRIPS Agreement imposes three conditions to be met for testing permissibility of exceptions or limitations to the exclusive rights. These conditions represent situations that are ‘certain special cases’, ‘[do] not conflict with a normal exploitation of the work’ and ‘[do] not unreasonably prejudice the legitimate interests of the right holder’. If these three conditions are met, a government may choose between different options for limiting the right in question, including use free of charge and without an authorisation by the right holder. The Panel, in interpreting these three conditions in US–Section 110(5) Copyright Act, applied the effectiveness principle, which requires the treaty interpreter to give a distinct meaning to each of the three conditions and to avoid a reading that could reduce any of the conditions to ‘redundancy or inutility’.39

B ‘Object and Purpose’ of the TRIPS Agreement

At the close of the Uruguay Round negotiations, developed countries considered Articles 7 and 8 only ‘hortatory’, whereas developing countries regarded them as describing the objectives and principles of the TRIPS Agreement affecting rights and obligations of the Members under the Agreement (see chapter 4). The question of what the ‘object and purpose’ of the TRIPS Agreement are has increasingly become contentious, as access to medicines and transfer of technology, as well as other possible public policy issues in IPR protection come to be debated. In these discussions outside the disputes settlement procedures, the legal statuses and the interpretative roles of Articles 7 and 8 TRIPS became divisive issues.

Only in a few dispute cases, have Panels and the Appellate Body dealing with TRIPS provisions been faced with the question of what the overall object and purpose of the Agreement is. In one of the earlier TRIPS dispute cases, India–Patents (US),40 the Appellate Body for the purpose of interpreting Article 70.8(a), referred to the Preamble, and said that: ‘The Panel’s interpretation here is consistent with the object and purpose of the TRIPS Agreement.’ According to the Appellate Body, the object and purpose of the Agreement is, inter alia, ‘the need to promote effective and adequate protection of intellectual property rights’.41

The identification of the ‘object and purpose of the treaty’ for interpreting TRIPS provisions, for the WTO dispute settlement organs, has been based mostly on textual analyses, with some exceptional cases where the Panel did not exclude considerations of facts and policies. In Canada–Patent Term,42 the Appellate Body stated that their task was to give meaning to the phrase, ‘acts which occurred before the date of application’, and to interpret Article 70.143 in a way that is in accord with the rest of the provisions of Article 70.1 and their context, having particular regard to the object and purpose of the treaty.44 In this case, however, the Appellate Body added that: ‘we note that our findings in this appeal do not in any way prejudge the applicability of Article 7 or Article 8 of the TRIPS Agreement in possible future cases with respect to measures to promote the policy objectives of the WTO Members that are set out in those Articles. Those Articles still await appropriate interpretation.’45

Two years later, the Panel Report in Canada–Pharmaceutical Patents dealt with the question of the ‘object and purpose’ of the TRIPS Agreement and,46 following the general rule of interpretation in accordance with Article 31 of the VCLT, identified what follows. Article 7 of TRIPS is not the only purpose of the TRIPS Agreement. Article 7 mentions that the purpose of the IPR system is the premise of the Agreement, and so the object and purpose of the treaty will also depend on other provisions. Even if the exceptions in Article 30 of the TRIPS Agreement allow certain limitations of the exclusive rights as provided in Article 28, they must not change the fundamental balance between the rights and obligations of the TRIPS Agreement. Thus, for the Panel in Canada–Pharmaceutical Patents, the ‘object and purpose’ of the TRIPS Agreement in the meaning of Article 31.1 VCLT is inferred from the general structure of the agreement in which the balance of rights and obligations is struck.

The Panel in EC–Geographical Indications explicitly stated that many measures to achieve public policy objectives are different from intellectual property protection itself, and therefore outside the scope of the TRIPS Agreement. The Panel explained that the nature of intellectual property rights provides for the grant of negative rights to prevent certain acts. This fact leaves Members free to pursue legitimate public policy objectives which normally lie outside the scope of intellectual property rights without resorting to exceptions under the Agreement. The Panel Report thus delineated the principles in Article 8.1 (see chapter 5, p 157).47

C Determining the Scope of Exceptions

i Are exceptions interpreted narrowly? From GATT to WTO

As stated earlier, the VCLT rule of interpretation does not include the axiom that ‘exceptions should be interpreted narrowly’. GATT Panels adopted this approach more often than the WTO dispute settlement organs, particularly concerning Article XX (see chapter 4). The most apparent difference between the GATT Panels and the WTO in dealing with ‘exceptions’, concerns the interpretation of Article XX GATT. In US–Gasoline, the Appellate Body stated:

The Appellate Body compared its approach with that under the GATT, and found a similar approach taken also by the GATT Panel, in the 1987 Herring and Salmon Report. The Appellate Body in US–Gasoline noted that:

. . . as the preamble of Article XX indicates, the purpose of including Article XX(g) in the General Agreement was not to widen the scope for measures serving trade policy purposes but merely to ensure that the commitments under the General Agreement do not hinder the pursuit of policies aimed at the conservation of exhaustible natural resources.49

The Panel in EC–Geographical Indications considered that most public policies are formulated outside IPR protection, without regard to the issue of IPR protection.50 However, there may be arguments that good public policies can be realised through the use of exceptions to IPRs, such as ‘fair use’ of copyrighted works or regulatory exceptions to patent rights. For example, the interpretation of Article 17 which refers to ‘fair use’ of descriptive terms could refer to some public policies.51 There may therefore be arguments that TRIPS exceptions must be interpreted widely to allow certain public policy objectives, such as public health or fair use.

Fundamentally for the WTO dispute organs, it is the VCLT rule, ie, the analysis of ‘the terms of the treaty in their context and in the light of its object and purpose’, that determines the perspective taken by the treaty interpreter. In what follows, the Appellate Body explains that the word ‘exception’ alone cannot determine how this provision should be interpreted:

The general rule in a dispute settlement proceeding requiring a complaining party to establish a prima facie case of inconsistency with a provision of the SPS Agreement before the burden of showing consistency with that provision is taken on by the defending party, is not avoided by simply describing that same provision as an “exception”. In much the same way, merely characterising a treaty provision as an “exception” does not by itself justify a “stricter” or “narrower” interpretation of that provision than would be warranted by examination of the ordinary meaning of the actual treaty words, viewed in context and in the light of the treaty’s object and purpose, or, in other words, by applying the normal rules of treaty interpretation.52

[the Court is] faced not with a choice between two conflicting principles [human rights of the individual and the restrictions necessary for democratic society] but with a principle of freedom of expression that is subject to a number of exceptions which must be narrowly interpreted.53

Many dispute settlement organs, including the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR), relied to some extent on the effectiveness principles54 but have developed their own policies of treaty interpretation without specifically referring to or turning away from the VCLT rule of interpretation. The Court referred to the VCLT rule of interpretation in early cases such as Golder v UK55 in 1975, before the entry into force of the VCLT.56 However, the ECHR developed its own interpretative principles, among which is the principle that exceptions should be interpreted restrictively when they concern self-standing rights/principles which cannot be easily balanced against other policy considerations, such as the right to freedom of expression provided in Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms. Ultimately, however, the ECHR also engages in a balancing exercise between different policies. For the WTO-covered agreements which are of a commercial nature, there seems to be no norm with authority that is automatically accepted and that stands out from others. The above difference in the interpretative methods relating to exceptions therefore concerns this kind of balancing. Significantly for the WTO Agreements, the question of burden of proof is important in arguing for exceptions.

ii VCLT and Exceptions and Limitations to the Rights Conferred under the TRIPS Agreement

The scope of exceptions or limitations to the rights conferred under the TRIPS Agreement may require special consideration. There are pre-existing IP conventions with provisions concerning exceptions to the rights conferred and specific provisions, relating to exceptions in the TRIPS Agreement, for separate categories of IPR. How provisions in the TRIPS Agreement concerning exceptions are interpreted, therefore, depends in part on how the treaty interpreter views the relationship between the relevant TRIPS exceptions provisions and provisions in the IP Conventions which are incorporated in the TRIPS Agreement.

According to the Panel in EC–Geographical Indications, the scope of the exceptions in the TRIPS Agreement must be interpreted based on the terms of the provision in their context, in light of the ‘object and purpose’ of the Agreement as follows:

The ordinary meaning of the terms in their context must also be interpreted in light of the object and purpose of the agreement. The object and purpose of the TRIPS Agreement, as indicated by Articles 9 through 62 and 70 and reflected in the preamble, includes the provision of adequate standards and principles concerning the availability, scope, use and enforcement of trade-related intellectual property rights. This confirms that a limitation on the standards for trademark or GI protection should not be implied unless it is supported by the text.57

The Panel responds to an argument made by Australia that there was an ‘implied limitation’ on the rights in Article 16 – implied from the relationship between Article 16 (which is in Part II – Standards concerning the Availability, Scope and Use of Intellectual Property Rights) and Articles 3 and 4 in Part I (General Provisions and Basic Principles) of the TRIPS Agreement. The Panel responded that such a limitation had to be supported by the text, and found that it was not so supported.58

iii Exceptions and public policy considerations

The Panels in US–Section 110(5) Copyright Act and in Canada–Pharmaceutical Patents examined extensively the scope of exceptions in Article 13 (entitled ‘Limitations and Exceptions’) and Article 30 (entitled ‘Exceptions to Rights Conferred’) of the TRIPS Agreement. Both Panels followed an interpretative method based on the customary rules of interpretation as understood and developed by the WTO dispute settlement organs in non-TRIPS cases, examined the extent to which pre-existing intellectual property treaty provisions were incorporated and looked into the negotiating history of the TRIPS Agreement. Although the Panel in US–Section 110(5) Copyright Act was innovative in its use of economic data, both Panels emphasized the wording of the relevant provisions which they analysed in detail. The Panel in Canada–Pharmaceutical Patents recognized public policy implications of Article 30 without, however, expounding on substantive issues.

a Article 13 TRIPS (Limitations and Exceptions)

The Panel relied basically on the VCLT method of interpretation to find the criteria for judging the scope of the exceptions and limitation under Article 13 TRIPS which provides that:

Members shall confine limitations or exceptions to exclusive rights to certain special cases which do not conflict with a normal exploitation of the work and do not unreasonably prejudice the legitimate interests of the right holder.

In this case, the European Communities and their Member States alleged that the exemptions provided in subparagraphs (A) and (B) of Section 110(5) of the US Copyright Act were in violation of the US’s obligations under Article 9.1 of the TRIPS Agreement, together with Articles 11(1)(ii)59 and 11 bis(1)(iii)60 of the Berne Convention (1971). Section 110(5) of the US Copyright Act provides for limitations on exclusive rights granted to copyright holders for their copyrighted work, in the form of exemptions for broadcast by non-right holders of certain performances and displays, namely, (A)’home style exemption’ (for ‘dramatic’ musical works) and (B)’business exemption’ (works other than ‘dramatic’ musical works, eg the playing of radio and television music in public places such as bars, shops, restaurants, etc). For the EC, the above exemptions under the US law could not be justified under any express or implied exception or limitation permissible under the Berne Convention (1971) or the TRIPS Agreement.61

Article 9.1 TRIPS stipulates that ‘Members shall comply with Articles 1 through 21 of the Berne Convention (1971) and the Appendix thereto . . .’. Article 13 of the TRIPS Agreement, in Section 1 concerning copyright and related rights, provides three conditions in which limitations and exceptions to exclusive rights are allowed. According to Article 13, ‘Members shall confine limitations or exceptions to exclusive rights to certain (i) special cases; (ii) which do not conflict with a normal exploitation of the work; and, (iii) do not unreasonably prejudice the legitimate interests of the right holder.

The Panel and the parties agreed that these conditions are cumulative because the principle of effective treaty interpretation requires that the Panel avoids any reading that could reduce any of the conditions to redundancy or inutility.62

The Panel found that the language of Article 13 TRIPS is similar to that in Article 9(2) of the Berne Convention, except that Article 9(2) applies only to the right of reproduction, whereas Article 13 has no such limitation. The Panel also noted at the outset that: ‘Article 13 cannot have more than a narrow or limited operation. Its tenor, consistent as it is with the provisions of Article 9(2) of the Berne Convention (1971), discloses that it was not intended to provide for exceptions or limitations except for those of a limited nature.’63 Having considered the examples of the minor exceptions in the context of the Berne Convention as well as national laws, the Panel concluded that Article 13 is a narrow exception which is allowed only if its scope is de minimis.64 This analysis was based on the wording of the provision in its context and facts from national laws, not because of the general principle that exceptions must be interpreted narrowly. In the light of the minor exceptions doctrine which was recognised as being incorporated into Article 13 of the TRIPS Agreement, the Panel analysed each term,65 first of all textually,66 but also through economic data which represented the actual and potential effects of the exemptions.67

The EC argued that the exceptions should be related to a legitimate policy purpose. In examining the scope and meaning of ‘certain special cases’, the Panel rejected equating the term ‘certain special cases’ with ‘special purpose’. The Panel explained that: ‘It is difficult to reconcile the wording of Article 13 with the proposition that an exception or limitation must be justified in terms of a legitimate public policy purpose’.68 According to the Panel, ‘special cases’ in Article 13 require that a limitation or exception in national legislation should not only be clearly defined, but also ‘narrow in its scope and reach’.69 Interestingly, the EC contended in this case that the US exemption is not based upon a ‘valid’ public policy or other exceptional circumstance that makes it inappropriate or impossible to enforce the exclusive rights conferred.70 The Panel did not interpret Article 13 of the TRIPS Agreement from an a priori conception of public policy, with the intention of achieving appropriate balance based on such conceptions.71 Interestingly, the Panel rejected the idea that the first condition of Article 13 requires ‘a value judgment on the legitimacy of an exception or limitation’.72

The Panel added, however, that ‘public policy purposes could be of subsidiary relevance for drawing inferences about the scope of an exemption and the clarity of its definition’. It then reiterated that what is important for the interpretation of Article 13 is that the statements from the legislative history indicate an intention of establishing an exception with a narrow scope, and that the intention of Article 13, which incorporates the context of Arts 11 and 11 bis of the Berne Convention (1971), is to allow exceptions as long as they are de minimis in scope.73

Concerning the second condition that exceptions must ‘not conflict with a normal exploitation of the work’, the Panel, after examining the ordinary meaning of the words, held that ‘normal exploitation’ means something less than the full use of an exclusive right74 and that work includes ‘all’ of the relevant exclusive rights attached to the work.

The US argued that whether or not the exception conflicts with normal exploitation should be judged by economic analysis of the degree of ‘market displacement’, ie, the forgone collection of remuneration by right holders. The Panel supported the EC argument that proof of actual trade effects has not been considered an indispensable prerequisite for a finding of inconsistency with the national treatment clause of Article III of GATT and it is rather ‘a potentiality of adverse effects on competitive opportunities and equal competitive conditions for foreign products, in comparison to like domestic products’.75 In applying this GATT model of analysis to a TRIPS case, the Panel explained that:

We wish to express our caution in interpreting provisions of the TRIPS Agreement in the light of concepts that have been developed in GATT dispute settlement practice. . . . Given that the agreements covered by the WTO form a single, integrated legal system, we deem it appropriate to develop interpretations of the legal protection conferred on intellectual property right holders under the TRIPS Agreement which are not incompatible with the treatment conferred to products under the GATT, or in respect of services and service suppliers under the GATS, in the light of pertinent dispute settlement practice.76

On the third condition of Article 13, ie, ‘not unreasonably prejudic[ing] the legitimate interests of the right holder’, the US argued that the focus should be placed on whether the right holder is ‘harmed by the effects of the exception’ and whether that prejudice is ‘unreasonable’. The Panel observed that this third condition implies a three-step test, ie, the determination of the terms ‘legitimate interests’ at stake and the extent of ‘prejudice’ to judge what amount of prejudice reaches the level of what is considered to be ‘unreasonable’.80 The Panel stressed the need to take into account potential revenue loss and the need for right holders to own their rights such that they can engage in agreements like collective management organisations in the first place. Based on the economic impact of the provisions in US law for ‘normal use’ and ‘legitimate interest of the right holder’ incurred by the exemptions,81 the Panel concluded that the US, which had the burden of proof in invoking the exception of Article 13, failed to demonstrate that the business exemption did not unreasonably prejudice the legitimate interests of the right holder.82

In US–Section 101 (5) Copyright Act, there was no debate on the dimension of public policy largely because of the wording of Article 13 of the TRIPS Agreement. According to the Panel, the phrase ‘certain special cases’ in Article 13 of the TRIPS Agreement is not the equivalent of ‘for a special purpose’ and does not refer to justifiable in the sense of normative policy (such as public policy or special circumstances). However, ‘for a special purpose’ is also included in ‘certain special cases’, so it is possible to interpret that Article 13 also has a public policy dimension. It would be possible under the TRIPS Agreement to consider public policy considerations for copyright protection to the extent that the scope of ‘minor exception’ allows.

b Articles 30 TRIPS (Exceptions to Rights Conferred)

The Panel in Canada–Pharmaceutical Patents84 adopted a method of interpretation even more textualist than that in US–Section 101 (5) Copyright Act in that it did not resort to economic data in judging whether the ‘regulatory exception’ (popularly called the ‘Bolar exemption’85) for drug marketing authorisation and the ‘stock-piling’ exception provided by the Canadian Patent Act86 could be considered to fall within the scope of exceptions provided by Article 30 of the TRIPS Agreement. Article 30 TRIPS provides that:

Members may provide limited exceptions to the exclusive rights conferred by a patent, provided that such exceptions do not unreasonably conflict with a normal exploitation of the patent and do not unreasonably prejudice the legitimate interests of the patent owner, taking account of the legitimate interests of third parties.

Canada, in interpreting the conditions of exceptions stipulated in Article 30 TRIPS to the exclusive rights conferred on the patent-owner under Article 28 TRIPS, called attention to Articles 7 and 8.1 TRIPS, as relevant to the object and purpose of Article 30.87 According to Canada, Article 7 declares that one of the key goals of the TRIPS Agreement was a balance between the IPRs created by the Agreement and other important socio-economic policies of WTO Member governments. For Canada, Article 8 elaborates upon the socio-economic policies in question, with particular attention to health and nutritional policies.88 With respect to patent rights, Canada argued that: ‘these purposes call for a liberal interpretation of the three conditions stated in Article 30 of the Agreement, so that governments would have the necessary flexibility to adjust patent rights to maintain the desired balance with other important national policies’.

The EC, on the other hand, argued that Articles 7 and 8 describe a balancing that had already taken place during the TRIPS Agreement negotiations and that the negotiations were not intended to allow a Member to ‘renegotiate’ the overall balance. The EC pointed to the last phrase of Article 8.1, which requires that socio-economic policies that Canada refers to must be consistent with the obligations of the TRIPS Agreement.89 For the EC, the first paragraph of the Preamble and Article 1.1 demonstrated that the basic purpose of the TRIPS Agreement was ‘to lay down minimum requirements for the protection and enforcement of intellectual property rights’.90

The Panel stated the view that ‘Article 30’s very existence amounts to a recognition that the definition of exclusive rights contained in Article 28 would need certain adjustments’, but that ‘the three limiting conditions attached to Article 30 testify strongly that the negotiators of the Agreement did not intend Article 30 to bring about what would be equivalent to a renegotiation of the basic balance of the Agreement’.91 The Panel considered that the exact scope of Article 30’s authority will depend on the specific meaning given to its limiting conditions. For the Panel, therefore, the scope of exceptions to the patent rights conferred must be determined by analysing the wording of Article 30 in the context of relevant TRIPS provisions, including Articles 7 and 8.1.

Article 30 of the TRIPS Agreement stipulates three conditions which the Panel considered to be cumulative.92 The exception must (1) be ‘limited’; (2) not ‘unreasonably conflict with normal exploitation of the patent’; and (3) not ‘unreasonably prejudice the legitimate interests of the patent owner, taking account of the legitimate interests of third parties’. The language of Article 30 resembles that of Article 13 TRIPS, since the drafters drew the same inspiration from Article 9(2) of the Berne Convention as they did for Article 13 TRIPS. However, in condition (3) of Article 30, in contrast to Article 13, the phrase, ‘taking account of the legitimate interests of third parties’ is added which, according to the Panel in this case, leaves room for public policy consideration.

Concerning the second condition, that exceptions must not ‘unreasonably conflict with a normal exploitation of the patent’, the parties differed on the meaning of ‘normal’. According to the Panel, the term ‘normal’ has a combined meaning of two possible dictionary meanings, ie, ‘what is common within a relevant community’, and ‘a normative standard of entitlement’.97 No economic criteria for judging whether the effects of the Canadian law ‘unreasonably conflict with a normal exploitation of the patent’ were developed or applied in this case. The Panel held therefore that a right to extended term of protection due to regulatory delays falls outside the bounds of ‘normal’98 as the patent term erosion of this kind is an unintended consequence of the conjunction of the patent laws with product regulatory laws, which is not applicable to the vast majority of patented products.99 For these reasons, the Panel concluded that Canada’s regulatory review provision does not conflict with a normal exploitation of patents under TRIPS Agreement Article 30.100

As for the meaning of condition (3) of Article 30, ie, that the exception must not ‘unreasonably prejudice the legitimate interests of the patent owner, taking into account the legitimate interests of third parties’, the Panel relied on the dictionary definition. It interpreted the word ‘legitimate’ as a normative claim calling for protection of interests that are ‘justifiable’ in the sense that they are ‘supported by relevant public policies or other social norms’, and then looked into the preparatory work of Article 9(2) of the Berne Convention. The Panel concluded that the concept of ‘legitimate interests’ in Article 30 are construed as a broader concept than legal interests.101 The EC invoked the time lost to the effective patent protection due to regulatory delays in obtaining marketing approval, but the Panel rejected the EC claim that this situation creates a ‘legitimate interest’ for the patent holder. The Panel asserted that this interest was ‘neither so compelling nor so widely recognized’ to constitute a ‘policy norm’ that would fall within TRIPS Agreement. According to the Panel, the concept of ‘legitimate interests’ should not be used to decide, through adjudication, a normative policy issue that was still obviously a matter of unresolved political debate.102 From this, the Panel concluded that Canada had demonstrated that the regulatory review provision did not prejudice ‘legitimate interests’ of affected patent owners within the meaning of Article 30.103

Thus, in evaluating the scope of exceptions allowed under Article 30, the Panel took a thoroughly ‘textualist’ approach. Intense discussions followed as to the extent to which this formalism is suited to intellectual property protection. The Panel’s extreme caution in confining itself to a textual approach for interpreting TRIPS provisions may partly be explained by the existence of potential political and industrial conflicts which could involve polarising debate. The formal, textual approach in Canada–Pharmaceutical Patents seems to have preempted endless political arguments, although the fact that no economic or social realities behind abstract concepts have been taken into consideration has left many other questions open to future debates.

The Panel in Canada–Pharmaceutical Patents stated that the non-discrimination rule delineated in Article 27.1 applied also to exceptions. This gave rise to various criticisms, including those relating to research tool patents in biotechnology, as we will see below.

D Non-Discrimination Principles in the TRIPS Agreement

i National Treatment Principle and IP protection

National treatment and most favoured nation principles, commonly called ‘non-discriminatory principles’, have been pivotal in trade liberalisation in goods throughout the GATT and the WTO history, and central to trade disputes and their settlement within these institutions. These principles are also enshrined in Part I of the TRIPS Agreement as basic principles, in Articles 3 and 4, respectively, but they had to be adapted to be applied to intellectual property owned by persons.

In the TRIPS context, these GATT principles apply specifically to the ways in which IPR ‘protection’ is accorded to nationals and non-nationals, which include, according to footnote 3 to Article 3, ‘matters affecting the availability, acquisition, scope, maintenance and enforcement of intellectual property rights as well as those matters affecting the use of intellectual property rights specifically addressed in this Agreement.’ In Indonesia–Autos,104 therefore, the US argued, as an ancillary complaint, that the Indonesian law and practices at issue, as far as they concerned the use of trademarks, were inconsistent with Article 3 TRIPS, national treatment and Article 20 of the TRIPS Agreement.105

The Appellate Body in US–Section 211 Appropriation Act considered that Article III:4 GATT, which concerns equality of competitive opportunities for domestic and imported products, could serve as a ‘useful context’, even to this TRIPS dispute.106 The relevant standard for its examination of Article 3.1 TRIPS concerning national treatment was ‘whether the measure provides effective equality of opportunities as between these two groups in respect of protection of intellectual property rights’.107 The Panel in EC–Geographical Indications, admitted further that the language of Article 3.1 is similar to the language of GATT Article III:4,108 but that the latter requires that ‘no less favourable treatment must be given to like products’. The Panel suggested that this combination of elements, the basic principles of GATT 1994 and of relevant international intellectual property agreements or conventions, characterises new TRIPS rules and disciplines as expressed in the preamble to the TRIPS Agreement.109

The Panel in EC–Geographical Indications examined whether the difference in treatment affected the ‘effective equality of opportunities’ for nationals of the defendant Member’s country with regard to the ‘protection’ of IPR, to the detriment of nationals of other Members.110 In this regard, the Panel quoted the Appellate Body in Korea–Various Measures on Beef