Asbestos compensation in Belgium

Chapter 2

Asbestos compensation in Belgium

An “historical champion in asbestos consumption”1 in which 200 people die every year of mesothelioma,2 Belgium is barely on the atlas of comparative legal scholarship, much less of comparative studies of asbestos compensation. Legal scholars have paid little attention to this small, bilingual country in the heart of Europe. Belgium, as historian Gerd-Rainer Horn pointed out, “remains one of Western Europe’s least well-known territorial states, certainly in academic circles outside of its national boundaries.”3 Nonetheless, Belgium is a very interesting case study of asbestos compensation because of its exceptionalism if compared to the other nations researched in this book: remarkably weak claim consciousness, absence of personal injury cases based on occupational exposure, and workers’ compensation as (almost) the only path to compensation (almost because in 2011 an asbestos personal injury case based on environmental exposure was successfully litigated for the first time).

The absence of personal injury litigation is remarkable. This is certainly the reflection of black letter law dictating workers’ compensation’s exclusivity as a remedy, unless the victim can prove that the employer intentionally caused the disease. This is a de facto immunity for employers. Furthermore, Belgian victims’ efforts to find ways to circumvent or to curb workers’ compensation exclusivity have been ineffective. Claim consciousness and mobilization have been weak. The roots of this state of affairs run deep into Belgian legal, political and socio-cultural tradition. The forces that compressed claim consciousness and mobilization include a powerful asbestos industry, slow emergence of medical studies on asbestos diseases, unfriendliness of rules, judicial and doctrinal attitudes towards occupational disease, a system of labor relations that failed to generate interest in asbestos compensation on the part of unions, and a political and legal culture that discouraged demands for justice in favor of quiet acceptance of asbestos disease as a misfortune.

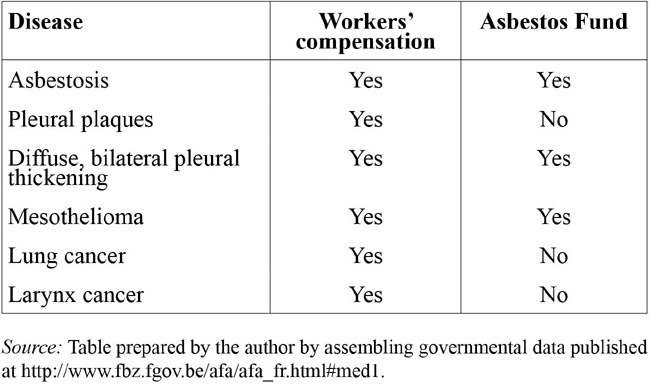

For five decades asbestos victims were not able to collect anything more than workers’ compensation, some additional payments from Eternit, and a few settlements. From 1953, the year in which asbestosis was listed in workers’ compensation, and 2011, the year in which the first and only judgment in Belgium’s history went in favor of an asbestos victim, workers’ compensation has been virtually the exclusive source of compensation for asbestos victims. During these five decades, the only payments that were consistently made to asbestos victims were sums paid by the workers’ compensation system to victims of occupational exposure. Currently, victims of occupational exposure receive compensation exclusively from the workers’ compensation system. Compensation was expanded in 2007 when the Fonds d’indemnisation des victimes de l’amiante, an ad hoc asbestos fund, was set up to curb some of the limitations of workers’ compensation.4 Victims of secondhand and environmental exposure are not entitled to receive payments from workers’ compensation or the 2007 Asbestos Fund. A few cases have been litigated and only one was successful. The chapter looks at each of these determinants of weak claim consciousness and mobilization, at the current workers’ compensation and the recent enactment of the 2007 Asbestos Fund, at growing efforts to mobilize claims, which have led to the only case that an asbestos victim has successfully tried. The discussion begins with an historical roots and developments of workers’ compensation.

Origin of workers’ compensation

The statutory exclusivity of workers’ compensation as means to compensate occupational disease and its conservative judicial interpretation have also contributed to weak claim consciousness and mobilization. Established in 1903, Belgian workers’ compensation is rather biased against claimants. This bias is the product of the historical circumstances that led to its establishment. The 1903 statute is the outcome of a contentious policy debate fueled by years of workers’ mobilization and fierce opposition on the part of business owners. Since the 1850s, workers had established mutuality companies that operated as small private funds that provided insurance coverage to workers with no direct involvement of government or industrialists. In the first few decades of operations, these funds helped injured workers cope with the dire consequences of industrial accidents and sowed the seeds of a culture of compensation. However, bringing tort cases was not easy: the rules of tort liability required workers to prove the employer’s negligence, and workers did not know how they could find this proof.

Progressive scholars engaged in some efforts to change the doctrine governing these cases from negligence to breach of contract. The proposed shift entailed holding employers civilly liable if, at the time of the resolution of the employment contract, the employee was in bodily conditions different from those at the time the employment contract had started. The adoption of this doctrine would have meant a substantial change in workers’ ability to recover damages for occupational disease: being based on a breach of contract, the burden of proof would have shifted to the employer, who, in the event of a worker having suffered a bodily injury in the course of employment, would have escaped liability only upon proof of force majeure (an Act of God) or the fault being with the victim (for example, although well trained, the victim failed to properly operate a certain machine). These progressive ideas were well received at the trial court level, but were rejected by higher courts.5

When the progressive movement was defeated, industrialists were already facing a new, more threatening danger of becoming accountable for industrial injuries: joining civil claims for damages to criminal trials. In 1878, Belgium adopted a new code of criminal procedure that allowed, for the time, the practice of joining civil claims to criminal trials. Indeed, victims took advantage of the new rules and began claiming compensation in criminal trials. However, as Pétré and De Simone noted, this practice was short lived:

Wealthy and well respected citizens, who happened to own a business, were increasingly required to appear in front of the tribunal correctionnel to defend themselves in criminal investigation for work-related injuries. This situation needed to change quickly. Workers needed to be discouraged from joining the claims for damages in criminal investigation for the purpose of obtaining compensation for harm caused by work-related injuries.6

Since workers did not seem to become “discouraged,” the solution needed to be found elsewhere. Therefore industrialists began lobbying Parliament to establish a no fault system that would be the exclusive remedy for injured workers. By 1903, Parliament had favorably received the idea and created a no fault system for the compensation of occupational injuries. This was the solution that industrialists had hoped for: the removal of claims based on occupational injuries and disease from the tort system. While, on its face, the new law looked an attractive social bargain that allowed workers to recover benefits without the need to prove the employer’s fault, in reality the 1903 reform crushed the emerging claims consciousness of the Belgian working class and established narrow boundaries for claiming for decades to come. As De Kezel noted, the exclusivity of the remedy was meant to disfavor conflicts among labor and capital by avoiding employees’ lawsuits alleging the employer’s fault.7 The system that was established was a closed one, that is, compensation was awarded only for prescribed injuries appearing on a list compiled by the King at his discretion.

The evolution of workers’ compensation

Workers’ compensation originated as a weak compromise for workers. In its original form, the system was rather unfriendly to workers: no diseases were included, it was not mandatory, and employers enjoyed tort immunity. For instance, a disease was compensable only in the event the person’s working capacity was lost in its entirety. This requirement pushed victims to file claims at a very difficult time of their lives, when they were near to death, or required the initiative of a surviving relative, who in addition to grieving needed to quickly activate the legal process to secure compensation rights. Furthermore, when claiming, victims needed to attach an affidavit signed by the treating physician, usually a general practitioner and not an expert in occupational medicine, certifying that the disease had been caused “with certainty” by occupational exposure. This requirement was particularly harsh. We have already seen how disengaged with regard to occupational diseases Belgian medical professionals had been and continued to be for decades. Also diagnosing an occupational disease is a task that may exceed the expertise and qualifications of general practitioners. It requires specialized knowledge, access to data on exposure to toxic substances in the workplace, and equipment to conduct proper tests. The fact that the affidavit to be attached to the claim did not need to be signed by an expert, often jeopardized the success of the claim because affidavits often failed to meet the medical expectations of the workers’ compensation administration. Workers’ compensation unfriendliness towards victims was soon noted by commentators. In 1935, Paul Hennebert, a Belgian physician, published in Travail et Droit, a magazine edited by the socialist labor union, a critique of workers’ compensation warning that many victims of occupational disease would be left with no compensation in the years to come: “To these sick people, the only option left is money paid by the mutualitées, as a form of emergency relief, or becoming beggars.”8

Throughout the years, workers’ compensation was to be refined, modified, and expanded. The first major transformation took place in the 1930s when workers’ compensation was expanded to include occupational diseases. This happened in 1927 when a separate body, the Fonds de prévoyance en faveur des victimes de maladies professionnelles, was established to compensate victims of occupational diseases.9 Initially, only three diseases were included, and none of them was an asbestos disease (the first known US workers’ compensation claim for asbestos disease was filed in 1927). A few more were then added in 1932. By the mid-1930s the list comprised diseases due to exposure to lead, mercury, coal, benzyl, sulfur dioxide, phosphorus, and radium. After the 1930s, new diseases were added at a very slow pace. The case of silicosis provides a good illustration: by the time occupational diseases were included in the workers’ compensation system, silicosis had been already known to be a lung disease caused by occupational exposure to dust. In the United States, legislation was introduced to protect workers from silicosis in 1919. In 1930, silicosis was discussed at the International Conference on Silicosis. In England, the Medical Research Council recognized increased claims of coal miners by the late 1930s. The Fascist regime listed silicosis in 1943 in an attempt to survival politically by pleasing industrialists who, by then, had been targeted by a growing number of lawsuits brought by silicosis victims. Notwithstanding scientific consensus and regulatory convergence towards compensating silicosis, Belgium prescribed silicosis only in 1963, after countless Belgian miners had already become victims of the disease. The reform was pushed by political pressure coming from Italian immigrants who were becoming sick after moving to Belgium to work in local coal mines. They knew that silicosis could be caused by occupational exposure because they had worked in Italy, where the disease had been prescribed since 1943.

Asbestos diseases were included only in 1950s. When workers’ compensation was established, asbestos was not yet a public health issue, and occupational diseases in general were not matters of particular concerns. Business owners were occupied and preoccupied with chopped hands and missing eyes. The asbestos industry was at that time nascent, and the perils of asbestos dust for the most part still unknown. Consequently no occupational disease was included among the range of compensable events. Asbestosis was the first to become listed in 1953 (23 years after England). Additional diseases were added after further delay: mesothelioma in 1982, pleura plaques and lung cancer in 1999, and cancer of the larynx in 2004.10 Very few applications for workers’ compensation benefits followed the inclusion of asbestos among the list of prescribed diseases mostly because of the rather narrow medical and exposure criteria set by the law. As Nay noted, “[b]ilateral parenchymatous lung fibrosis, presence of asbestos bodies in the sputum, and an alteration of either the heart or lung function were required.”11 Furthermore, “[o]nly those employed in the asbestos cement sector, in the asbestos textile industry, or in the manufacture of asbestos products were entitled to compensation.”12 The definition of asbestosis was expanded in 1964: “fibrosis of the pleura and other pleural lesions became compensable occupational diseases.”13

Workers’ compensation became mandatory only in the 1970s. Before that time, employers could choose to be self-insured or to stipulate policies with private insurance companies. For many years employers could choose whether or not they wanted to insure employees. Many did not. The system was restructured in 1971 and only then it became compulsory for employers. The system was reformed again in the 1990s, when it became a mixed system allowing victims of non-listed disease to attempt to recover benefits provided they could establish that their disease was caused by their occupation.14

Although workers’ compensation was reformed in the twentieth century, some of the structural features that were since unfriendly to victims from its inception—employer’s immunity is the most prominent—will never be touched by reform. The slow, conservative transformation of the welfare state is the product of the dynamics of its evolution. Rather than having a state engaged in labor relations as Mussolini’s “corporatist” state, the Belgian welfare state was primarily developed by bipartite intersectoral agreements negotiated by labor and trade unions.15 This system, which governed labor relations from the 1940s to the 1990s, was institutionalized in the form of a hierarchical pyramid in which the top bounds the bottom through a series of intersectoral agreements that established principles and pillars of negotiation at the company level. Power at the pyramid’s top was monopolized by “successive generations of political elites” who had strong ties to industrialists, trade and labor union leaders and took personal credit for the socioeconomic achievements of high growth, full employment, and a comprehensive welfare system.”16 Belgian political institutions played a weak role. This is not surprising since political power is highly fragmented and Belgians have “shaky confidence in the functioning of democratic institutions.”17 Vilrokx and Van Leemput talk about “vulnerability of institutions,”18 a vulnerability that is clear in the context of asbestos. The lack of teeth to bite private companies and enforcing workers’ rights is evidenced by labor inspectors’ difficulty in accessing workplaces to monitor asbestos levels. In a confidential interview with journalist Vandemeulebroucke, a labor inspector indicated that “employer’s duty to monitor the presence of asbestos in the workplace exists only on paper.”19 Enforcing asbestos regulations is almost impossible as employers “do not have the guts” to monitor asbestos.20 This framework of bipartite agreements and weak state intervention enabled the asbestos industry to dominate labor relations.

A powerful asbestos industry

Asbestos firms were part of the group of powerful and politically well-connected interests, and they were able to direct the welfare state towards a friendly path of immunity. The asbestos industry has its roots in Belgium’s early industrialization. Partly helped by the wealth generated from its colonies, Belgium played a key role in sectors that fueled the second industrial revolution. Mining, shipbuilding, railroads, and textiles are among the industries that flourished. Belgian industrialization was fueled by its propensity to import and transform raw materials. The colonies were excellent sources of imported raw materials, which were logistically moved around the country easily thanks to a well-developed, efficient system of ports and transportations. Asbestos was one of these imports—primarily from Cyprus and South Africa. A prosper industry grew out of the commercial exploitation of the magical mineral in the early twentieth century.

The context in which the asbestos industry has operated is important in understanding the limited claim consciousness among asbestos victims. Although Belgium underwent early industrialization, over time it lagged behind. Its industrial sector was not as rapid in developing and adjusting to modernization and technological advances in each industrial sector. Ron Boschma demonstrated that, following the first industrial revolution, Belgium failed to develop clusters of innovation or developed them with a considerable delay.21 Slower innovation is linked to the familial, occasionally feudal, structure of corporate governance. The structure of major corporations is such that it concentrates remarkable power in order to exercise intra- and extra-sector influence. The Belgian asbestos industry illustrates these points well.

The asbestos sector was led by Eternit, now part of Etex, which became affiliated with Saint-Gobain of France and more informally to other asbestos-cement manufacturers throughout Europe, exported its asbestos production as far as Brazil and India, and eventually became the world’s second largest seller of asbestos products. Eternit’s main manufacturing facility was located in Kapelle-op-den Bos, a small town with a railroad and canals around which a host of smaller asbestos manufacturing firms also flourished. In the mid-1960s, Eternit also purchased the Coverit asbestos-cement plant, which was located in Harmignies and had employed roughly 200 men, 40 women, and 40 minors.22

Eternit shareholders were powerful and influential members of aristocratic circles and the highest ranks of diplomacy. Krols and Teugels also report that the other Eternit shareholders are key players in the political and economic life of the Royaume de Belgique:

The shareholders of Eternit Belgium belong to the old nobility. By the beginning of the twentieth century the Emsens were already a wealthy business family with connections to the Belgian court. Members of each of its several branches occupy, or have occupied, positions at the top of Eternit companies. These include Baron Louis de Cartier de Marchienne; Jean-Marie, Stanislas and Claude Emsens; and Paul Janssen de Limpens.23

Production sites owned and operated by other asbestos firms popped up all over the small country since asbestos was used in a variety of industries. Shipbuilding in particular sustained the industry as the port of Antwerp acquired commercial prominence to then become the third-largest seaport in continental Europe in the first part of the twentieth century and one of the few ports that had not been completely destroyed during World War II.

Foreign influence was also important in the industry’s growth. For example, the English clan the Cockerills brought machinery and technology from Britain and was subsequently rewarded with political protection. By 1812, the Cockerills had established in Liège a machine-building plant that employed over 2000 workers.24 Furthermore, Mol hosted the first overseas plant—producing asbestos-cement—owned and operated by US asbestos giant Johns-Manville from 1928 to 1983.25 Johns-Manville also owned a plant in Gent from 1962 until 1983. In 1983, the plants employed collectively 540 workers.26 Finally, the most influential presences consisted of the Schmidheinys—the owners of Eternit Suisse and the most influential family operating in the asbestos business. Tycoon brothers Stephan and Thomas profoundly influenced the Belgian asbestos industry directly, by holding shares and sitting on the board of Eternit Belgium, and though the lobbying activities of the Comité d’Information de l’Amiante Benelux (CIAB), which had been operating since 1970 coordinating the lobbying efforts of firms in Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg. CIAB is still operating, with an office in Brussels.27 The powerful role of Belgian asbestos firms is also demonstrated by the fact that asbestos was still heavily used when other industrial nations were moving away from it. In 1980, asbestos per capita use, measured in kilos, in Belgium was 3.23 while in the US it was 0.77 and 0.87 in Great Britain. Similarly in 1990 per capita use was respectively 1.61, 0.08, and 0.18.28 Also, asbestos was banned only in 1997, and that asbestos production completely ended in 2002.29

The Belgian asbestos industry avoided public scrutiny for decades. In 1977, two Belgian investigative journalists, Marie-Anne Mangeot and Salvator Nay, sought permission from the management of Coverit, a large cement-asbestos plant located in Harmignies, in the French-speaking part of Belgium, to enter the factory and interview workers. The firm denied the request indicating that it was undergoing substantial renovations to transform the plant into a state-of–the-art facility and that images of a messy plant filmed during renovations would have misled the public and not depicted the reality of the firm.30 The effects of professional and environmental exposure in Harmignies were only publicly acknowledged in 2005 in an issue of the Belgian weekly magazine Le Soir Magazine. The title of the journalistic investigation was simple: Coverit counts the dead.31

Public scrutiny was avoided by establishing a culture of secrecy. The Eternit Group, which was the major asbestos firm, led these efforts. The Group exercised tight control on its share circulation and its managers were part of the families that owned shares or individuals trusted by those families. As Krols and Teugels point out, its structure was “feudal:” “Top management had far more direct contact with leading political officials than with ordinary workers.”32 Further, the Belgian companies established strong business, corporate, and political connections with the other asbestos firms in Europe. Among them, the Swiss Schmidheiny brothers, who owned a substantial portion of Eternit shares, held corporate interests in several major Swiss companies, including Swissair, Nestlé, Swatch, UBS, ABB, and the cement group Holcim.33 These international connections made the Belgian industry stronger and well shielded from domestic public scrutiny.

Eternit also proactively offered payments to victims in exchange for a release of any claim. These agreements however are confidential and we know very little about which victims signed them and what happened to them. In the 1980s, Eternit set up a compensation fund for similar reasons. This private plan made payments to victims who became sick either because they had worked at the manufacturing plants located in Kapelle-op-den-Bos and Tisselt or because they lived in the proximity of the plant.34 In its original form, the fund only offered payments to workers below the age of 65 and affected by asbestosis resulting in a degree of disability exceeding 33 percent. They were offered payments equal to the difference between the workers’ compensation benefit and their last salary. In 2000, the fund was expanded to include former employees who had developed mesothelioma. The fund was further expanded to victims of secondhand exposure in 2001 and to victims of environmental exposure in 2006. Overall at least two asbestosis victims and 70 mesothelioma victims were compensated, including 12 victims of household exposure and two of environmental exposure. In 2007, the year in which the plan was closed down after the establishment of the 2007 Asbestos Fund, the payment amounted to EUR 43,171.35

Labor unions and their lack of interest for asbestos compensation

Although union membership and union density in Belgium are high if compared to other corporatist welfare capitalist countries, unions have not significantly contributed to the mobilization of asbestos victims. In 2003 Salvator Nay noted that “local unions remained, for most of the twentieth century, ignorant of the problem.”36 In Mortel Amiante, his 1997 monograph entirely devoted to asbestos in Belgium, Nay pays very little attention to unions.37 Unions are mentioned occasionally in interviews with asbestos workers. However, although several victims were union members, none of them acknowledges any substantial contribution of unions in the emergence of claim consciousness among victims. Overall, labor unions have held ambivalent positions with regard to asbestos and their advocacy at the national level has had very little impact in terms of workers’ mobilization at the local level. Their agenda did not include workplace safety and asbestos compensation as a priority. The top concern was salary stability and the preservation of the welfare system.

Unions could, however, have made a difference. Labor unions were in fact deeply involved in the highly institutionalized system that dominated labor relations until the 1970s. Unions dominated workers’ participation at the workplace level. An incentive to join a union came from a peculiarity of the system. In Belgium, unemployment benefits are paid by unions and not by the government. Hemerijck and Marx further argue that this mechanism increased and maintained workers’ loyalty towards unions for decades, even in times of growing unemployment and overall worsening of the working conditions.38 National leaders would negotiate bipartite agreements at the national level and local representatives would translate intersectoral agreements into agreements at the company level. The top down approach was rarely challenged by local unions and workers. Even among the ranks of socialist unions, which had the strategic objective of workers’ control in the 1950s as a “halving of employers,” opposition was mostly neutralized.39

The top down approach operated so effectively and led to almost uncontested normalization of labor relations, even though socialist and Christian unions had divergent views on how to protect workers’ rights, because of what Vilrokx and Van call “compensation democracy.” This feature placated the conflict of interest that invested labor unions leaders in negotiations “by acceding to the demands of one interest group while at the same time providing additional resources to compensate the other groups involved.”40 In the end, since labor negotiations resulted in collective agreements that generated sufficient benefits to all of the social actors involved, labor union leaders were justified in giving up some of the original demands in exchange for any negotiated benefit. Unions’ activities have been for the most part fragmented and uncoordinated at the local level. Strikes were occasionally organized by asbestos workers. However no union brought together asbestos workers from different companies and mobilized them in demanding better working conditions and more generous compensation as has happened in England and Italy. Union advocacy was primarily directed towards policy reform at the national level with very minimal spillover effect at the plant level.

In the aftermath of 1968, workplace safety issues did not become part of the political discourse of labor relations, as they did in Italy. During the 1968 protest, workers joined students’ protests to organize strikes and other initiatives in major industrial sites throughout the country. Labor unions however rarely backed the protests. Workers’ protests were essentially coordinated by grassroots organizations that had no tie to labor unions. As Horn noted, official unions frequently refused to sanction strikes and other forms of protests.41 Ultimately “militant grassroots-impelled labor actions” of the late 1960s failed to shake Belgian politics and society “to its foundation.”42 Its legacy was for the most part lost in translation during the 1970s especially because Belgium was severely hit by the oil crisis of 1973. Because of its high levels of unemployment, its reliance on international trade, and the low rate of innovation, the oil shock brought tougher times to Belgium than to other European economies. Belgium has traditionally had low levels of employment and low levels of poverty, a combination that is often labeled as “welfare without work.”43 In the 1970s, the split between grassroots groups and labor unions became more marked. The radical fringes of grassroots movements converged politically towards the Far Left and the Revolutionary Workers’ League, a political group that, although active throughout the 1970s, was never able to have an impact on Belgian political life. The less radical fringes converged politically towards the New Left, which throughout the 1970s adopted a moderate approach towards social issues. The close ties of political parties with the asbestos industry did not allow much room for negotiation of a “new” welfare and labor unions worked towards preserving the “welfare without work” model rather than venturing into the unchartered territory of workplace safety. During the 1970s, the most popular labor union was the Confédération des syndicats chrétiens, a Catholic labor union that “appeared to be … prepared … to accept and support the workplace occupations and especially the self-management initiatives.”44 However, Catholic labor unions have traditionally pursued a less adversarial agenda in industrial relations. This approach was well-suited to the difficult economic times that Belgium faced in the aftermath of the 1973 oil crisis. In 1976, bipartite negotiations failed to reach an agreement for the first time in Belgium’s history. The state stepped in and forced an agreement on social parties. The state’s primary concern was international competitiveness in the face of a weak decade from an economic perspective. As a consequence, throughout the 1970s and 1980s, unions did not favor workers’ mobilization but negotiated a progressive shift of the welfare system from a social insurance system for members of the workforce to a minimum income protection system redressing the risk of becoming poor associated with severe unemployment rates that happened in the 1970s. Welfare policies included early retirement for many asbestos workers, and industrial restructuring was facilitated by low resistance from trade unions and workers.45

In the 1990s, labor relations focused once again on competitiveness which led to the the tripartite agreement of 1966 on “linking wages in Belgium to those of its three main trading partners [France, Germany and the Netherlands], through what by now is called a ‘wage norm’.”46 This was seen “as the only possible (consensual) way to restore the country’s competitiveness and to halve unemployment by the end of the century.”47 The need to balance wage increase with wages’ purchasing power monopolized labor relations in the 1990s. Even at this juncture though, the retrenchment of the welfare state was more modest than in other industrialized nations. Despite the adoption of neoliberal policies, workers, especially those in sectors that had been affected by the economic downturn or, like asbestos, that were on the verge of disappearing, received favorable packages to be “bought off” in affected sectors.48 This yielded to low industrial conflict and unions’ modest interest in asbestos compensation throughout the 1990s.

Low industrial conflict throughout the 1990s had implication for asbestos compensation. Negotiations expanded the list of prescribed asbestos diseases (lung cancer in 1999 and larynx cancer in 2004). However, unions refrained to support workers’ compensation litigation, which was by contrast a prominent feature of asbestos compensation in Italy by then. The reasons are several. First, labor unions had operated with a mindset shaped by a culture of compensation democracy that defined the Belgian experience of labor relations. Gains could be obtained only by negotiating them in exchange for giving up certain demands. Litigating workers’ compensation eligibility or challenging the administration’s decision clashed with this culture. Furthermore, personal injury litigation was feared to be a bottom-up source of unbalance and destabilization of labor relations at national level. Preserving employers’ immunity under workers’ compensation was necessary, labor unions thought, to preserve the system of compensation democracy that curbed the retrenchment of the welfare state. Finally, litigation of both workers’ compensation eligibility and personal injury claims was a threat to the unions’ primacy as the legitimate representatives of the working class and to union membership. If courts expanded the class of asbestos victims eligible for compensation, in particular non-union members who were victims of secondhand exposure and environmental exposure, unions would not have been able to claim the legitimacy to represent these victims, a situation that could have led to further decline of union membership and erosion of their ability to effectively represent workers in the political process.

Labor unions’ ambivalent attitude towards workplace safety and lack of interest in supporting expansion of asbestos compensation through litigation have certainly deprived asbestos victims of crucial support to foster claim consciousness and mobilization. Workers’ compensation policies were never challenged to the extent to which they have been in Italy and England and no efforts were made to find ways for victims to bring personal injury cases to court by circumventing or reforming the rule of workers’ compensation exclusivity and employers’ immunity. In particular, no attempts were made to use the strategy that brought significant results in Italy—that is, joining civil claims to a criminal trial.49 The lack of asbestos trials is not the result of Belgian criminal procedure being based on an inquisitorial model. The distinction between adversarial and inquisitorial systems is “outdated” theoretically.50 The legal framework set up by the Italian code of criminal procedure and the Belgian code are in the end very similar. The Belgian legal system has in fact developed along the same historical trajectories of Italy and France. Historically Belgium has been profoundly influenced by the continental legal culture, and in particular French legal culture. Belgium’s Civil Code was enacted by Napoleon in 1804 when Belgium was a French territory. After independence, the Napoleonic Civil Code was not repealed as Belgium’s cultural life was still very much dominated by French influence, which was reinforced by the assistance that the French government offered in Belgium’s fight for independence from the Dutch in the 1930s and the economic domination of the French-speaking industrial south. Similarities between Belgium and Italy’s criminal procedure systems offer to asbestos victims similar incentives to join their claims to public prosecutions. Labor unions also have incentives as they can recover damages, as they do in Italy, for loss suffered indirectly (in Italy this is also possible and labor unions have been able to recover damages for the loss of image suffered as a result of unions’ alleged inability to effectively prevent employers’ criminal noncompliance).51 What have been missing in Belgium are the mobilization preconditions that were present in Italy: prosecutors have never targeted asbestos companies (no asbestos firms and executives have ever been tried in Belgium for asbestos crimes) and neither labor unions nor activists took the initiative to press charges and did not contribute to ensuing investigations. Consequently, the few victims that sought compensation in court brought civil claims for damages in civil courts.

The failure of victims to use criminal investigation as a vehicle to bring claims may have also been the result of the doctrinal fragmentation of the Belgian legal system, which fails to provide strong doctrines. Traditionally, Belgian legal culture has been dominated by France. This is particularly true in the areas of liability and insurance law. More recently, as the importance of Dutch language has grown, the influence of law from the Netherlands has become more prominent, causing a fracture between legal mentalities originating from different legal traditions, the French and the Dutch. Legally, Belgium is experiencing a deep identity crisis. This crisis certainly failed to provide asbestos victims with effective legal tools—doctrines and arguments—to mobilize demands.

Slow emergence of medical studies on asbestos diseases

Despite Belgium’s history of asbestos use, epidemiological studies have not been conducted for many years. In 2007 Bianchi and Bianchi in the review of the global incidence of mesothelioma noted that “[s]carce data are available for Belgium.”52 The lack of public scrutiny of Belgian asbestos firms is certainly correlated to the late emergence of epidemiological data on asbestos disease. In addition, gathering medical data was difficult because the Belgian authorities release no individual information contained on death certificates. An ad hoc mesothelioma registry has never been established, contrary to the common practice of other European countries.

Surveys of the health conditions among asbestos workers appeared late, and, to further detriment, these early attempts to monitor asbestos disease were sponsored by asbestos firms. Eternit in particular commissioned two studies. In 1950, Clerens found that Eternit’s asbestos-cement workers were “in good health.”53 The study was known by Selikoff, who cited Clerens’s work in the literature review of one of his landmark papers of the 1960s that established the link between asbestos and lung cancer.54 As we will see later, in the aftermath of the study, the Belgian legislature decided to include asbestosis among the list of prescribed diseases under workers’ compensation. The second study appeared almost two decades after. In 1967, Eternit commissioned a second study looking at mortality in the population living in its plant’s neighborhood. Van de Voorde and colleagues55 found that the mortality from cancer was “twice the national rate in the 13 neighboring villages,” but they also found similar mortality rates among the residents of the 13 villages included in the control group.56

The two Eternit-sponsored studies found very little evidence of asbestos impact on asbestos-cement workers. The first crack in the wall took place in 1973 when Vande Weyer, a pneumologist who had worked for the workers’ compensation administration, published a paper that reported statistics discussing the 20-year history of compensation for asbestosis.57 This is the first time data at national level were made public. The picture that emerged was dramatic. The study, which comprised 138 patients with asbestosis who had received workers’ compensation, included 51 patients who had died. Data showed that four out of five deaths had been caused by asbestosis or its complications. In addition, one patient out of five had also developed a form of cancer—lung cancer and mesothelioma in respectively 20 percent and 7 percent of the cases. Although the data clearly showed that asbestos was killing Belgians, the study did not trigger a public debate on the merits of asbestos production. The only study that was conducted immediately after Weyer’s publication was done by an unknown physician in a small town, Dr. Modave, who instigated asbestosis studies in the industrial area of the Basse Sambre on a cohort of workers employed in a company that quietly closed down its asbestos production in 1977, thus disappearing from the list of asbestos companies. The authors found 19 cases of asbestosis among the outpatients of a local hospital and were able to assert the occupational origin of all of them. Dr. Modave’s findings were published in a low profile journal.58 His paper remained unknown to professionals and to the general public for years. A copy was retained in Lyon, France, at the offices of IARC, the UN agency devoted to the study of cancer, and retrieved by a British activist, Nancy Tate, only years after its publication.59 Studies were subsequently published in later years, but medical evidence in Belgium accumulated over time at a rate comparatively slower than in other Western countries. The only opportunity for public debate of asbestos toxicity presented itself when the Belgian press picked up on the news that a group of French consumers had voiced their concerns with regard to asbestos filters that were used by wine producers in neighboring France. As the public became somewhat concerned with the magical mineral, the industry activated its spin doctors and “bought full-page advertisements in the main newspapers to reassure consumers.”60 Furthermore, in statements to the press, industry representatives indicated that any case of asbestosis was “the result of working for many years in a very dusty environment that had existed 20 years earlier but that was now a thing of the past” and that no Eternit worker had been affected by mesothelioma.61

While the 1970s ended with very little debate about asbestos toxicity, the wind changed in the 1980s. In 1980, Lacquet and colleagues studied the annual chest radiographs, work history and mortality of 1,973 subjects exposed at the Eternit plant of Kapelle-op-den Bos (although the study refers to the plant as an “unnamed asbestos-cement factory”).62 They reported one death due to pleural mesothelioma and 29 cases of asbestosis.63 In 1981, Weyer published a follow-up to his earlier study. The second study discussed 267 new cases of asbestosis that had been filed in workers’ compensation between 1972 and 1981. With respect to the 1973 study, more subjects had died of cancer (19 percent of mesothelioma and 25 percent of lung cancer), bringing the percentage of asbestos victims with cancer to 75 percent of the claimants who had received workers’ compensation benefits.

In the 1980s, another significant step forward happened: the routinization of data collection regarding cancer. In fact, in 1983 the government stepped in and established the National Registry of Cancer. Before 1983, data was hard to access. Data on malignancies was not collected systematically and firms were not required to, and thus did not, disclose them. Unions often provided the only source of reliable data. Since the 1950s, unions began to gather medical information on their members by obtaining data from the treating physician and organizing this data into databases. The 1983 implementation of the National Registry of Cancer represented an important step forward because collected data become public and therefore unions and other interested parties could easily access it. Between 1985 and 1992, the Registry recorded 630 cases of mesothelioma.64 While an excellent new source of data in the asbestos debate, the system was not perfect: data reporting was not compulsory, and doctors and hospitals were not required to report any data. Data reporting become mandatory only in 2003 when the National Health System required that hospitals submitted to the Registry information regarding cancer cases in order to receive any reimbursement from the care provided to cancer patients. In addition, a standardized form was distributed to the hospitals so that data could be collected more systematically.

Another important, but incomplete, source of data on asbestos disease was represented by the Belgian Fund for Occupational Diseases. Weyer’s 1973 and 1981 papers brought to light data on compensation for claims submitted by asbestos victims. However, in the early days only asbestosis was listed and therefore many other asbestos diseases was missed and could not form the basis of a workers’ compensation claims. Furthermore, many asbestos victims were not entitled to compensation because they were either working for employers who were not included in the system or victims of household or environmental exposure. The point is clearly illustrated by looking at data from 1985 to 1992: while the National Registry of Cancer recorded 630 cases of mesothelioma, the workers’ compensation system recognized 232 claims based on mesothelioma, less than 40 percent of those recorded nationally. Notwithstanding these limitations, the statistics published by the Belgian Fund for Occupational Diseases are an important source of data on asbestos disease. They reveal that, between 2000 and 2004, 203 deaths were attributed to asbestos. Based on this data, Nawrot and colleagues estimated an asbestos mortality of about eight per million men per year65—a figure higher than in any of the 33 countries studied by Lin and colleagues, including England and Italy.66

Currently, more epidemiologists are studying asbestos disease more closely. For instance, Hollevoet and colleagues, whose primary interest is in biomarker-based early detection of mesothelioma, conducted a multicenter study of more than 500 asbestos victims, some of whom had worked at Kapelle-op-den-Bos and Gent. They note that more than one hundred of the research subjects had been diagnosed with cancer caused by exposure to asbestos.67 However the protracted lack of access to and publication of epidemiological and pathological data, for which the medical profession is in part to be blamed, has affected asbestos compensation: medical evidence is a key tool in generating the kind of understanding that leads to developing the awareness and desire to demand compensation. Claim consciousness depends upon the realization that an injury exists and that the injury did not occur randomly but that similar harms have affected individuals who share similar features, exposure to asbestos in our case.