The Economic Torts

15

The economic torts

AIMS AND OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter you should be able to:

■ Understand the essential elements for proving deceit

■ Understand the essential elements for proving malicious falsehood

■ Understand the essential elements for proving passing off

■ Understand the essential elements for proving conspiracy and inducing a breach of contract

■ Critically analyse each tort

■ Apply the law to factual situations and reach conclusions as to liability

We are used to the law of torts dealing with interference that has caused loss or damage to property or physical injury. We have already seen from the law on pure economic loss that the courts are less willing to become involved where economic loss is concerned (see Chapter 6.2). One of the traditional reasons given for this was that in character such loss was more appropriately compensated in the law of contract.

However, there are a number of torts that can be loosely grouped together and which are concerned with interference with a person’s economic interests. They may represent an interference with a person’s livelihood and include deceit and malicious falsehood and also can include passing off and a range of other specific ways of interfering with a person’s trade.

15.1 Deceit

Deceit has a lot in common with and indeed is often associated with misrepresentation in contract law. It is a well-established tort that occurs when an entirely false representation is made that causes loss to a claimant who relies on the false statement. It was first recognised as early as the eighteenth century.

CASE EXAMPLE

Pasley v Freeman [1789] 3 Term rep 51

In this case the defendant falsely represented to the claimant that a third party to whom the claimant wished to sell goods on credit was in fact creditworthy. In fact this was entirely false and the claimant suffered loss as a result of the transaction. He was nevertheless able to recover for his loss through the tort of deceit.

The significance of the tort is that a successful claimant is able to recover not just for fn-ancial loss but for physical loss or injury also.

CASE EXAMPLE

Burrows v Rhodes [1899] 1 QB 816

The claimant here was persuaded through a false representation to take part in the ‘Jameson Raid’. He was able to recover under the tort for the physical injuries he sustained.

The tort is interrelated with the action for negligent misstatement and with misrepresentation in contract law. On this basis its significance may have reduced somewhat as a result of the Hedley Byrne principle and of the Misrepresentation Act 1967 since it is arguably harder to prove than either. However, the tort does enjoy a different measure of damages which may still make it a worthwhile cause of action.

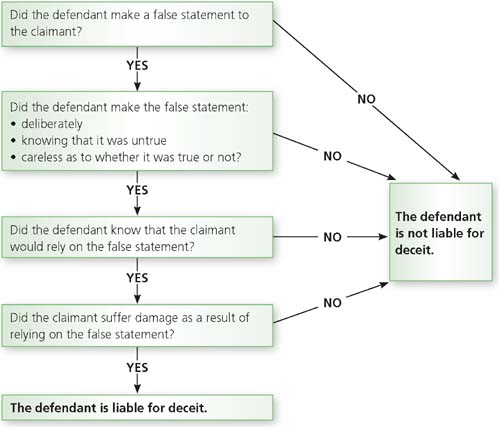

The requirements of the tort of deceit are:

■ that the defendant makes a false statement to the claimant or a class of people including the claimant;

■ that the defendant knows that the statement is false or is reckless in making it;

■ that the defendant intends that the claimant will rely for his conduct on the false statement;

■ that the claimant does indeed suffer damage as a result of having relied on the statement.

The making of a false statement

Generally a misrepresentation must concern a material fact in order to be actionable and must not be only a mere opinion.

CASE EXAMPLE

Bisset v Wilkinson [1927] Ac 177

Here in response to a request by the purchaser of land the vendor made a false statement concerning the number of sheep that the land being sold would support. There was no liability. The statement could not be relied upon since the vendor had no knowledge or expertise in the area and it was merely an unsupported opinion.

Of course a misrepresentation concerning a material fact may be actionable where the person making it has specialist knowledge.

CASE EXAMPLE

Esso v Marden [1976] QB 801

In this case the petrol company represented the likely sales of petrol to the person who was contracting to take a franchise of a petrol station. The statement could be relied upon because of the superior specialist expertise of the party making it.

While opinions are not classed as statements of fact it may be a false statement of fact to misrepresent an opinion or knowledge which is not actually held.

CASE EXAMPLE

Edgington v Fitzmaurice [1885] 29 ch D 459

The directors of a company falsely stated that a loan would be used to improve the company. In fact their intention all along was to use the money to repay very serious debts that were owed by the company. The misrepresentation of a future intent in these circumstances was sufficient to amount to an actionable falsehood.

It will also amount to a false statement to fail to correct a true statement that has later become false.

CASE EXAMPLE

With v O’Flanagan [1936] Ch 575

A doctor was selling his practice which was said during the negotiations for the sale to be worth an annual income of £2,000. The practice actually lost patients, and thus income, prior to the completion and the doctor’s failure to inform the purchaser of this fact amounted to an actionable misrepresentation.

It is also possible that a person who makes a false statement can be personally liable for deceit even though the misrepresentation is made on behalf of another party if all of the other elements of the tort are satisfed.

CASE EXAMPLE

Standard Chartered Bank v Pakistan National Shipping Line (Nos 2 and 4) [2002] 3 WLR 1547

A company, Oakprime Ltd, agreed to supply bitumen to a Vietnamese buyer with payment to be by letter of credit issued by Vietnamese bankers and confrmed by the claimant bank. The letter of credit required delivery before a specific date but loading of the bitumen was delayed until after that date. Mr Mehra, the managing director of Oakprime, then agreed with the shippers to insert a false shipping date in the documents. The claimant bank then authorised payment but was unable to recover from the Vietnamese bank because it had failed to notice that the documents were not in order. The claimant successfully sued both the shippers and Mehra. Mehra was held liable even though he had engaged in the deceit for the company. The court rejected a defence of contributory negligence since the defence was held not to be available in the case of a fraudulent misrepresentation.

Knowledge that the statement is false

The appropriate test of knowledge is the classic defnition explained by Lord Herschell in Derry v Peek [1889] 14 App Cas 337. The test identifes the need to show a fraud which is hard to show.

CASE EXAMPLE

Derry v Peek [1889] 14 App cas 337

A tram company was licensed to operate horse drawn trams by Act of Parliament. Under the Act the company would also be able to use mechanical power by first gaining a certificate from the Board of Trade. The company made an application and also issued a prospectus to raise further share capital. In this, honestly believing that permission would be granted, the company falsely represented that it was able to use mechanical power. In the event the application was denied and the company fell into liquidation. Peek, who had invested on the strength of the representation in the prospectus and lost money, sued. His action failed since there was insufficient proof of fraud. Lord Herschell in the House of Lords defined the action as requiring actual proof that the false representation was made ‘knowingly or without belief in its truth or recklessly careless whether it be true or false’

The test required that fraud must be proved which would mean that the misrepresentation had been made:

■ knowingly; or

■ without belief in its truth; or

■ reckless as to its truth.

It would appear that where an employee acts in the course of his employment in committing a deceit then the employer is likely to be vicariously liable for the false statement. The same principle is likely to apply in the case of agents and their principals also.

Intention that the statement should be acted upon

For the deceit to be actionable the defendant must also have intended that the statement would be acted upon. However, only those people falling within the class that intended to act upon the statement are able to sue.

CASE EXAMPLE

Peek v Gurnley [1873] Lr 6 hL 377

Statements in a share prospectus were not intended to be acted upon other than by those to whom the prospectus was actually issued. As a result the court could not fnd that there was any liability for deceit.

In this way the representation need not be made personally to the person who relied on its truth.

CASE EXAMPLE

Langridge v Levy [1837] 2 M & W 519

The claimant bought a gun from the defendant who knew that the claimant intended his son to use it. The defendant falsely stated that the gun was sound and when the gun blew up in the son’s face injuring him the defendant was held to be liable.

CASE EXAMPLE

Caparo v Dickman [1990] 1 All ER 568

Here shareholders in a company bought more shares and then made a successful takeover bid for the company. When they wished to back out of the takeover they failed in their claim that they relied on the audited accounts prepared by the defendants that had shown a sizeable surplus rather than the deficit that was in fact the case. The House of Lords decided that the false statement could not found an action since the company accounts were a requirement of company law and are not prepared for those taking over the company. The fact that it was foreseeable that there was a possibility of the claimants relying on the audit was insufficient on its own for liability. It must have been in the defendant’s mind at the time of the falsehood that the claimant was intended to rely on the falsehood.

Reliance on the statement

Actual reliance is also a necessary feature of the tort. The claimant must show that he did in fact act on the statement and suffer detriment as a result.

CASE EXAMPLE

Smith v Chadwick [1884] 9 App cas 187

The claimant bought shares in a company whose prospectus falsely stated that a certain known infuential person was a director of the company. In fact this false statement was of no significance at all since it was shown that the claimant had not in fact heard of that person and so could not have relied on the statement in entering the transaction. There was no liability.

The false statement need not be the only reason that the claimant acted as he did. It is sufficient in demonstrating reliance that it was one reason for acting.

Damage suffered by the plaintiff

For any action the claimant must inevitably have suffered loss or damage as a result of relying on the false statement for his course of conduct. The loss may be economic loss, or personal injury or property damage or indeed even distress and inconvenience.

CASE EXAMPLE

Archer v Brown [1984] 2 All ER 267

The claimant entered a partnership as a result of the defendant’s deceit. In his successful action the court held that he should recover the cost of shares, interest on a loan needed to buy the shares, as well as loss of earnings and damages for injury to feelings all of which were losses caused by the deceit.

CASE EXAMPLE

Doyle v Olby (Ironmongers) Ltd [1969] 2 QB 158

In this case Lord Denning indicated that the measure of recoverable loss was based on direct consequences irrespective of whether or not the loss was foreseeable. The case involved a deceit made during the sale of a business that the business involved counter sales when it was in fact based on employment of a sales representative. The claimant was able to recover a sum equivalent to the difference in the value of the business acquired from that represented as being true during the sale and also expenditure in running the business, including the cost of employing a representative. The measure of damages was thus far superior to that which would have applied to the breach of contract.

ACTIVITY

self-assessment questions

1. Is the action for deceit still relevant since Hedley Byrne and the Misrepresentation Act 1967?

2. What effect does specialist knowledge have in bringing an action for deceit?

3. What state of mind must a defendant have in order to be liable for deceit?

4. What degree of reliance does the claimant have to show in order to recover on the deceit?

5. For what loss can a claimant recover in a deceit action?

KEY FACTS

| Deceit | Case |

| The tort has a lot in common with misrepresentation. | |

| The requirements of the tort of deceit are: | |

| ● the defendant makes a false statement to the claimant or a class of people including the claimant | Derry v Peek [1889] |

| ● the defendant knows that the statement is false or is reckless in making it | Derry v Peek [1889] |

| ● the defendant intends that the claimant will rely for his conduct on the false statement | Peek v Gurnley [1873] |

| ● the claimant does rely on the false statement | Smith v Chadwick [1884] |

| ● the claimant suffers damage as a result | Archer v Brown [1984] |

| Damages can be recovered for all loss that is a natural consequence of the breach. | Doyle v Olby (Ironmongers) [1969] |

In simple diagram form the tort can be shown as in Figure 15.1.

15.2 Malicious falsehood

Introduction

The tort is in fact probably less an individual tort in its own right and more a generalisation of specific cases and is also sometimes referred to as injurious falsehood. Inevitably it is to do with loss caused to a claimant’s livelihood or reputation as a result of a false statement made by another. The significant addition is the ‘malice’.

CASE EXAMPLE

Ratcliffe v Evans [1892] 2 QB 524

A newspaper printed an article falsely stating that the claimant had gone out of business. It did so with the intention of causing harm to the claimant and his business. He sued successfully for his resultant business losses. The Court of Appeal distinguished from the very specific requirements of defamation and decided that the tort could result in liability in respect of any malicious statement that resulted in damage even where defamation could not be shown.

The tort has its origins in an action formerly referred to as slander of title. This was a very specific action based on the false questioning of a person’s title to land with the result that it became less saleable or even unsaleable. In the nineteenth century the tort extended to include slander of goods, based on similar principles.

More recently the tort has developed in a more general sense as a protection of people’s economic and commercial interests.

CASE EXAMPLE

Kaye v Robertson [1991] FSR 62

This involved a famous television actor, Gordon Kaye. He was injured and journalists published photographs and a story about his injuries, falsely stating that the story was produced with the actor’s permission. An action for malicious falsehood succeeded, the loss being that it prevented him from marketing the story himself and receiving payment for it.

In this way the tort can be used even where the loss is somewhat speculative in character.

CASE EXAMPLE

Joyce v Sengupta [1993] 1 All ER 897 cA

Here the claimant had been falsely accused in a newspaper article of stealing private letters from her former employer, Princess Anne. Her action was successful because of the potentia damage to her employment prospects

Even though it is potentially very broad in its scope, the tort has a number of distinct elements:

■ The defendant must have made a false statement about the claimant.

■ The statement must have been calculated to cause damage to the claimant.

■ The statement must have been made to a third party.

■ The statement must have been made maliciously. IThe statement must have caused damage to the claimant.

A false statement about the claimant

The statement must be false. A mere advertising puff is not accepted as being believable by the courts and so is not actionable, for example ‘Carlsberg, probably the best lager in the world’ need not be problematic.

However, false statements that actually run down a competitor’s goods may well be.

CASE EXAMPLE

De Beers Abrasive Products Ltd v International General Electric Co of New York [1975] 2 All ER 599

Here the defendants published what was alleged to be a ‘scientific study’ falsely denigrating the claimant’s products in order to boost sales of their own products. They were liable under the tort.

Where the statement does not refer to the claimant at all then it will not be actionable even if it causes damage to the claimant.

CASE EXAMPLE

Cambridge University Press v University Tutorial Press [1928] 45 RPC 335

The claimants argued that they had suffered damage when the defendants had falsely stated that it was their own book that was recommended by an examination board, when in fact it was the claimants’ book that was recommended. There could be no liability within the tort since there had been no reference to the claimants, even though they had allegedly suffered a loss of sales.

Calculated to cause damage to the plaintiff

The word calculated in the context of the tort merely means that loss or damage to the claimant was foreseeable.

In this way only specific references to the claimant rather than general ones are likely to be actionable. Two cases can be compared on this point.

CASE EXAMPLE