Vietnam: A Review of the Legal Framework and Enforcement

Country

Annual R&D Budget (USD),

% of GDP

No patent applications, no

granted per year

% patents granted

to citizens

Brunei

$1.5M (2003), 0.026% (2002)

23 app, 23 granted (2005)

0%

Myanmar

—-

—-

—-

Cambodia

$12M (2002), 0.053% (2002)

—-

—-

East Timor

—-

—-

—-

Indonesia

$55M (2004), 0.054% (2001)

3492 app, 2902 granted (2003)

—-

Lao PDR

$0.6M (2002), 0.036% (2002)

7 app, none granted (2005)

n/a

Malaysia

$600M(2002), 0.69% (2002)

4800 app, 6749 granted (2006)

1.5% (2005)

Philippines

$48M, 0.3% (2004)

2431 app, 1666 granted (2005)

0.9% (2005)

Singapore

$4B, 2.25% (2004)

9164 app, 7390 granted (2006)

5.8% (2006)

Thailand

$300M (2004), 0.24% (2002)

6340 app, 533 granted (2005)

14% (2005)

Vietnam

$71.3M (2002), 0.5% (2003)

1864 app, 649 granted (2005)

3.9% (2005)

Source: Kilgour L (2008)[9]

Industries that experienced a decrease in CR4 have seen significant growth in the last decade and most of them are light industries. The emergence of new entrants (particularly private and foreign firms) following deregulation led to a more competitive market structure which had previously been under the control of a few big state enterprises. For instance, from 2004 to the end of 2006, in the five industries that experienced the largest decrease in CR4, the net number of new entrants increased by as much as 125 per cent (from 2,464 to 5,489 enterprises).

On the other hand, CR4 rose in some other industries. There are three possible explanations for this:

1. The number of firms withdrawing from the industry or re-structuring were larger than the number of new entrants due to unfavourable markets conditions.

2. A small number of highly efficient firms expanded their market share at the expense of less efficient firms, for example in the textile industry.

3. In some industries, the Government simply combined a number of formerly independent SOE firms operating in the same industry to form a big state firm (for instance, in the tobacco industry). This occurred in a wide range of industries (19 in all), ranging from military-related products to publishing, tobacco, postal services, etc.

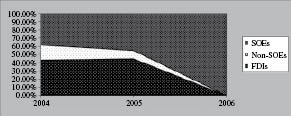

ii. Ownership of Dominant Firms

As far as ownership of the top-three firms is concerned, the biggest proportion (over 50 per cent) is not surprisingly controlled by the State, and foreign-invested enterprises come second with around 30–35 per cent. Less than 20 per cent of them are privately owned (see Figure 1). These original findings are important and provide new evidence of the dominance of the state-owned sector in Vietnam. Despite the fact that markets have been gradually

Figure 1: Ownership of Top-Three Firms in All Industries

Source: Authors’ compilation from GSO data.

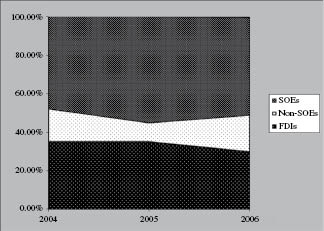

Figure 2: Ownership of Top-Three Firms in 20 Most Concentrated Industries

Source: Author’s compilation from GSO data.

liberalised and entry barriers notably reduced, the vast majority of over 120,000 private enterprises are still of SME size—of which 91 per cent having charter capital of less than VND10 billion (equivalent to merely US$500,000) and 98.77 per cent employing less than 300 employees. Meanwhile, 76 state-owned corporations and business groups alone account for up to 40 per cent of GDP and 28.8 per cent of domestic revenues (excluding crude oil and tariff revenues).[10]

A noteworthy fact is that, in 2004–05, the proportion of non-state sectors in the top-three firms of the 20 most concentrated industries was more or less the same as the average of the whole economy. However, by the end of 2006, all the top-three firms in the 20 industries were SOEs (see Figure 2). This finding is important in the sense that alongside other indicators of the dominance of SOEs, it shows the prompt impact in the change of market structure in industries assigned to be controlled by the so-called Korean style economic groups (tap doan kinh te) formed recently by administrative decrees of the Government.[11]

C. R&D Expenditure

Although its economy is largely based on agriculture activities, science and technology (S&T) has long been regarded as the important factor for development. However, there is a lack of authoritative and reliable data available on the total expenditure on research and development (R&D) in the country or even that type of data for each sector.

As a matter of fact, innovation is not currently regarded as part of Vietnam’s core development policy. However, the Government has begun considering whether to strategically invest in R&D to ‘position itself for future moves up the value chain’.[12] The table below shows that in the Southeast Asia region, Vietnam spends much less than Singapore and Malaysia in terms of annual budget for R&D as a percentage of GDP, but much more than other countries in the region. However, the number of patent applications and number of patents granted per year in the country is by far the least, if not counting poorer countries of Myanmar, Cambodia, East Timor, Lao PDR or the small-sized economy of Brunei.

According to an empirical study on the impacts of the IP system on economic growth using publicly available data, Tran Ngoc Ca et al[13] argue that it is very difficult to use econometric models to separate the impact of IP policy on economic growth. The main findings from the study are as follows:

[I]n the case of Vietnam, the impact of IP policy is not significant and effective due to some possible reasons: (i) The lack of public awareness about IP; (ii) The capacity of IP creation is weak. In industrial sector, as a consequence of low budget for R&D activities, the number of patents, utility solutions and industrial designs submitted to the NOIP is very small. Economic agents inclined to focus on creating and registering for trademark protection rather than creating other IP assets such as patents or designs. (iii) the inappropriate enforcement of IP laws and regulations. There are many infringements happened in the domestic markets without strong punishment to the violators. The court system is still not familiar with civil and criminals lawsuits relating to IP.

Although the econometric regression models’ results have not showed a significant impact of IP on socio-economic development, specific cases might show a relatively strong relationship between IP system and their business performance. So, in evaluating the impact of IP on economic growth, it is preferable to conduct small scale surveys of specific industries or specific activities, such as exportation or FDI attraction. Take the export indicator for example. In Vietnam, exports of primary goods and material account for a large proportion of total exports, therefore, it would not be surprising if the IP system has a small impact on export activities. However, it is undeniable that in many cases, IP assets, particularly trademarks, are of significant importance to a company penetrating into new markets overseas.

One survey by the National Institute for Science and Technology Policy and Strategy Studies (NISTPASS) on the impact of the IP system on FDI in the Vietnamese motorbike manufacturing industry shows that FDI firms, especially large companies such as Honda, Yamaha, etc perceive the importance of IPR issues. Those companies frequently have to deal with infringements of their product designs once they are launched to market and cause large economic damage in the context of weak enforcement of IPRs in the country.[14] Another survey of FDI companies operating in different sectors found that, in evaluating the decision to invest in Vietnam, FDI firms consider that IPRs and related activities are not among the most important issues.[15] A consequence is that few foreign firms invest in technology-intensive sectors, but rather almost all of them focus on labour-intensive industries to make use of the advantage of cheap labour in the country. Recent research also shows that the FDI firms are least effective in terms of efficiency (evaluated by ICOR (Incremental Capital Output Ratio) and TFE (Total Factor Efficiency))[16] in comparison with its state-owned and domestic private counterparts. Nonetheless, up to the present date, there is no reliable research focusing on the impact of the IP system toward business performance.

In a study on the links between innovation and export of Vietnam’s SME sector, Nguyen Ngoc Anh et al[17] found that innovation as measured directly by ‘new products’, ‘new production process’ and ‘improvement of existing products’ are important determinants of exports by Vietnamese SMEs. Evidence of the endogeneity of innovation was found. The study showed that all three measures of innovation, namely product innovation, process innovation and modification of existing product, are important determinants of exporting. This finding is important in the sense that in case endogeneity is not taken into account, biased estimate of innovation may be a result. As part of the process of joining the WTO and fully integrating with international markets, Vietnam was required to build and enhance a wide range of market-oriented legal systems. Among them was the introduction of competition and IP laws which are of crucial importance. Laws covering both were passed in the same year (2005). Not long afterwards, governmental decrees guiding the enforcement of competition and IP law were promulgated. The following part discusses in detail the essences of two laws, as well as their intersections in Vietnam.

III. Background to Competition Law and IP and their

Intersection in Vietnam

A. IP Laws

In the past, IP protection was not considered important in the centralised economic system run by the Vietnamese Government. It was believed that creative ideas belonged to the public and should be used to serve people in general. Although the country had joined international agreements on IP protection decades ago (as a member of the Paris Convention and Madrid Treaty since 1949 and the Stockholm Convention on the foundation of the World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO) since 1976), it delayed domestic regulations in the field until the introduction of a market economy following the Doi Moi policy. The first invention patent was granted in 1984 and the Ordinance on Intellectual Property Protection was issued in 1989. Legal documents were not systemised and only met international standards on IP protection when the country submitted its application to join the WTO.

The Civil Code (1995) was the first law that provided detailed provisions on IP protection in part 4 with 61 articles concerning IP rights and technology transfer. In 2005, Vietnam revised this part of the Code to constitute the first Intellectual Property Law. The Law regulated protection measures for IP rights, including copyrights, industrial property rights and rights to plant varieties:

— Copyrights are the rights of organisations and individuals to works created or owned by them and related rights of organisations, individuals to performances, phonograms, broadcasting programmes, satellite signals carrying encrypted programmes.

— Industrial property rights are the rights of organisations and individuals to inventions; industrial designs; layout-designs of semi-conductor integrated circuits; trademarks; trade names, geographical indications, business secrets created or owned by them and rights to repression of unfair competition.

— Rights to plant varieties are the rights of organisations and individuals to the new plant varieties which are created or discovered and developed by and fall under the ownership right of such organisations or individuals.

The IP provisions broadly followed international laws and agreements, especially after they were amended in 2008 to meet the requirements of the Berne Convention and the Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) Agreement when the country became an official member of the WTO. The Vietnamese Government is currently in the process of preparing for new guidelines.

B. Competition Law

The Competition Law was passed in the National Assembly in December 2004 and took effect from July 2005. The Law included the following provisions:

— Prohibition of competition restriction agreements, abuse of dominant or monopoly position and economic concentration when the combined market shares of undertakings exceed 50 per cent of the total market.

— Prohibition of unfair competition practices that go against business ethics and harm consumers and other businesses.

— Establishment of Competition Authority and Competition Council under the Ministry of Trade (ie Ministry of Industry and Trade now) to enforce the law nationwide.

— Establishment of competition procedure to review and apply remedies to violations of the law.

The Vietnamese Competition Law was developed with help from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) and followed their suggested model of competition law for developing countries.

It was officially stated that the main purpose of the law was to create an environment of fair competition and to promote a competitive market structure in Vietnam. On the other hand, some people believe that one of the reasons behind the introduction of the law was the Government’s concern about threats from larger multinational companies that could enter the domestic market after it opened its economy in accordance with WTO commitments. This was on the basis that in many countries, competition law had proved itself as an effective tool in deterring market power and protecting local SMEs as well as consumers.

Meanwhile, similar to China’s Unfair Competition Act 1993, the Competition Law of Vietnam included a provision requiring all government entities not to intervene unreasonably with market activities and to create negative impacts on competition. The provision is typical for competition acts in transitional countries where government entities ran the economy in the past and do not want give up their involvement in business life. However, this attempt to prevent this from happening has not worked well in practice.

IV. Intersection Issues

Vietnamese laws cover a number of horizontal and vertical issues, namely compulsory licensing and licensing contracts and unused patent. However, but the laws fail to provide a systematic approach to the intersection area, as well as enforcement proxies for IP and competition authorities to deal with relevant cases.

A. Compulsory Licensing

Regulations on compulsory licenses were first introduced in the Civil Code 1995. Article 802 of the Code (under part 4 on IP protection) provides that:

On the basis of the request of the person who has the need for use, the authorized State agency may issue a decision compelling the owner of an invention, utility solution or industrial design to transfer with remuneration the right to use the industrial property right in the following circumstances:

— The owner of the property does not use or use the property not in conformity with the requirement of social and economic development of the country without any plausible reason.

— The person who has the need to use the property right, after exhausting his/her means to come to an agreement with the owner of the property and having offered the reasonable price, still is refused by the author to sign a contract on the transfer of the right to use the industrial property objects.

— The use of the industrial property objects aims to meet the needs of national defense and security, medical treatment for the people and other urgent needs of society.

Since part 4 of the Code was split and developed by the Intellectual Property Law 2005, the new law provided more detail about compulsory license issues. General principles of compulsory licensing are stated in section 7.3 as follows:

In the circumstances where the achievement of defense, security, people’s life-related objectives and other interests of the State and society specified in this Law should be guaranteed, the State may prohibit or restrict the exercise of intellectual property rights by the holders or compel the licensing by the holders of one or several of their rights to other organizations or individuals with appropriate terms.

Under IP law, compulsory licensing can be applied to owners of inventions and plant varieties. Inventions are subjected to compulsory licensing following a decision from a competent authority regardless of the consensus of the owner in the following cases:

— When it is necessary to serve public interests, non-commercial purposes, national defence and security, disease prevention and treatment, nutrition for people or other urgent needs of the society.

— When the owner of the invention or his/her exclusive licensees fail to fulfill the obligations to use such invention to serve public and national interests within four years from the registration date and three years from the date of granting the patent.

— When a person fails to reach a reasonable agreement with the owner within a reasonable time for negotiation on price and conditions.

— When the owner of a dependent invention, which makes an important technical advance and economic significance, fails to request the owner of the main invention to license such principal invention with reasonable price and conditions.

— When the owner of the invention is considered to be exercising anti-competitive practices prohibited by competition law.

On the other hand, the law also limits compulsory licensing as follows:

— Compulsory license is not exclusive, ie the licensee shall not enjoy an exclusive right of using the invention.

— Compulsory license is limited in scope and duration that is sufficient to meet licensing objectives, and largely for the domestic market.

— The licensee is not allowed to transfer the use of license, unless he/she sells all of his/her business.

— The licensee has to pay the owner a reasonable licensing fee based on the economic value of the invention in real conditions and compliant with the compensation bracket set by the competent authority.

— The owner of the main invention may request the grant-back licensing of a dependent invention with reasonable price and conditions.

In any case, the owner of the invention has the right to request the termination of the compulsory license when the bases for licensing no longer exist and are unlikely to recur, provided that such termination shall not be prejudicial to the licensee.

Compulsory licensing on plant varieties is provided in article 195, with conditions and limitations similar to those applied to invention.

B. Licensing Contract

In order to prevent IP owners from misusing or abusing his/her exclusive rights, IP Law does not allow any contract term that imposes unreasonable restrictions on a licensee, particularly those that do not derive from the rights of the licensor by nature as follows:

— Prohibiting the licensee to improve the industrial property object (trademark excluded), compelling the licensee to transfer or grant-back to the licensor any improvements of the industrial property object free of charge.

— Directly or indirectly restricting the licensee to export goods produced or services related to licensing contract to a country/territory where the licensor neither holds the respective industrial property rights nor has the exclusive right to import such goods.

—