Libraries, Creativity and Copyright

Chapter 3

Libraries, Creativity and Copyright

This chapter explores the question ‘What is and what ought to be the relationship between cultural heritage institutions, creativity and copyright?’ Analysis is in two parts. In the first part we discuss the state of the current relationship between these three. In the second part we move on to elucidate what the relationship should – or could – be.

We write from practical experience at the National Library of Scotland (NLS). NLS is the largest library in Scotland, embodying 325 years of heritage. Between us we have the perspective of one who runs NLS as a library and one who specialises in intellectual property management for the Library. Additionally, we bring broader views gained through work in most types of cultural institutions, including archives, museums, galleries, universities and archaeology.

Cultural Heritage, Creativity and Copyright: The State of the Relationship

The Role of Institutions

Cultural heritage institutions are privileged to exist with the primary (if not sole) purpose of collecting, maintaining and affording access to society’s cultural material. These organisations have for centuries been in prime position to support both the strength of collective memory and the cumulative diversity of creativity. It is this foundational role of cultural heritage institutions in the expansion and development of creativity that is of particular interest here. This role for the sector is only set to increase in significance as technologies enable ever greater content access and connectivity between peoples. The cultural heritage sector is, uniquely, positioned within this expanding ecosystem to facilitate access to the existing corpus of knowledge. In other words, cultural heritage institutions hold and provide access to that which has gone before.

Libraries

Libraries have come over time to fill a particular remit within what can today been seen as the broader range of cultural heritage institutions. With a focus on the printed and recorded word, libraries have over centuries collected a vast proportion of humanity’s written output. Such collecting has formed incredible resources. However, as explored in more detail below, the remit of the library is by no means limited to the written word. Image, audio, cartographic material, databases and other forms of recorded content are very much at home in today’s library collections. The library itself, as well as hosting an almost unbounded range of content, can arise in almost any guise. Perhaps the most readily obvious forms of library are those that exist on the local level (public libraries), those that exist within educational bodies (e.g. university libraries) and those that record and maintain national collections – national libraries.

A collecting privilege that is often, although not exclusively, unique to national libraries is the right of legal deposit. In the United Kingdom, this right is presently afforded by terms laid out in the Legal Deposit Libraries Act 2003. The Act begins by stating the fundamental logic of legal deposit: ‘A person who publishes in the United Kingdom a work to which this Act applies must at his own expense deliver a copy of it to an address specified (generally or in a particular case) by any deposit library entitled to delivery under this section’.1

As a particularly complex country, the UK in fact operates not one but several deposit libraries with entitlement under this Act. Five domestic libraries – the British Library, the National Library of Wales (Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru), the National Library of Scotland (Leabharlann Nàiseanta na h-Alba), the Bodleian Library, Oxford and the University Library, Cambridge – as well as the Library of Trinity College, Dublin in the Republic of Ireland are entitled to legal deposit of UK publications. Not only, therefore, does the UK’s legal deposit framework cross between national and university libraries, it also crosses international borders. While the UK’s legal deposit establishment has helped to ensure that institutions around the British Isles have collected printed output with some consistency for over three centuries, the scope of this framework has also been gradually expanded over this period. UK legal deposit libraries have been collecting recorded sound and visual material (photographs, film, and related content), in addition to print, for over a century. In 2013 the scope of the Act was widened further to include works produced in non-print format (for example, web content).

This facility for mandated collection means that deposit libraries have accumulated collections significantly more expansive than those held by other types of cultural heritage institution. Taking the Scottish cultural sector as a contained example within the greater UK ecosystem, the National Galleries of Scotland have a permanent collection of just over 96,000 major art works2 (and a complete collection of around half a million items, when content such as photographs and documents are included), while the National Museum of Scotland houses around three million items. By contrast, the National Library of Scotland holds in excess of 24 million physical items in its collection, equivalent to some two and a half billion pages of content. The National Library’s legal deposit entitlement plays no small part in this collection disparity.

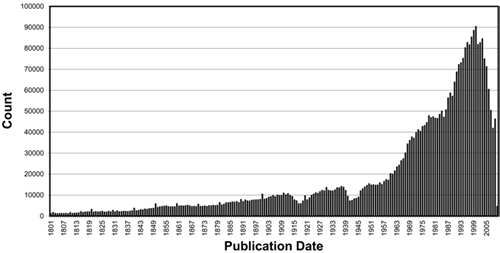

Figure 3.1 National Library of Scotland collections by publication date

In both the operating model of the library and the collecting framework of legal deposit privilege there is inherent non-discrimination. Library collections hold fact and fiction, acclaimed literary masterpieces and routine technical manuals. Likewise, libraries have content access at the core of their purpose and function. The National Library of Scotland is incorporated under the National Library of Scotland Act 2012, a piece of legislation which clearly spells out the institution’s obligations to the nation. Inter alia, the National Library exists with the mandate to ‘make collections accessible to the public’, exhibit and interpret its collections, promote collaboration, encourage education and research, and contribute to the development of ‘Scotland’s national culture’.3 The library operating model, more broadly, is most frequently access to content free at the point of use. In the case of legal deposit libraries, this means access to millions of unique and varied items. Centuries of collecting, whether within or outwith legal deposit legislation, means that libraries such as the National Library have built up an accessible, open repository of past creative processes that is available for current use and secured for future application.

Because legal deposit libraries are able to collect with such breadth and depth, they provide collections that are representative as well as large. However, legal deposit library collections also benefit from being filled with raw data material and interpreted content. The institutions designated under legal deposit legislation have changed and morphed over time, but the fact remains that libraries in the UK, in one guise or another, have been entitled for centuries to ensure deposit and retention of a copy of any work printed in the country. As impressive as the scale and diversity of the National Library of Scotland’s collection is, as a secondary legal deposit library within the UK’s uniquely complex system, the collection is in fact only about one-quarter the size of the country’s largest library collection: that of the British Library.

Unlike the National Library of Scotland or any of the four other legal deposit libraries, the British Library is the location where publishers are obliged to deliver their content – the National Library of Scotland and the others, while entitled to claim a copy, must specifically request that copy. This structure means that the British legal deposit framework encourages both comprehensive collection (British Library) and the development of distinct national or specialist collections (the five other libraries). This means that, when the National Library of Wales focuses on collecting Welsh publications and the National Library of Scotland ensures collection of Scottish publications, these libraries in fact hold countless items that are likely not to be found in any other (legal deposit) library.

Non-Print Legal Deposit

While library collecting approaches developed significantly over time, particularly in the twentieth century as new mediums of content became common (such as film and sound), the core of legal deposit legislation changed little. The Legal Deposit Libraries (Non-print Works) Regulations 2013, which supplement the 2003 Act, granted the framework one of its most fundamental expansions. The 2013 Regulations themselves are in fact fairly straightforward, and almost entirely mirror the process laid out in the 2003 Act for deposit of printed material. Crucially, the non-print regulations are not solely a web-collecting mandate, although evidently that is a huge and vital entitlement within them.

The 2013 Regulations allow the six legal deposit libraries to mandate timely delivery into their collections of works published in non-print format, in addition to ‘traditional’ print deposits. Such non-print works can be online material or offline material (for example, works encoded on a CD or similar data storage device). It is worth bearing in mind, however, that the 2013 Regulations exclude published material consisting only of sound recording, film recording or a combination of the two. This can be seen as fairly analogous to printed material deposit legislation, which does not include audio or moving image material. Indeed – in many respects – the 2013 Regulations are as liberal and conservative as existing legal deposit was previously: the British Library remains the site of ultimate collection, where works must be deposited, while the remaining five libraries may request material that they wish to be deposited in their own collections. All of this means that the 2013 Regulations allow UK legal deposit libraries to collect a far greater bulk of published material than was previously permissible, while continuing to enable distinct collecting strategies to be pursued at the different libraries.

Since taking effect on 6 April 2013, the 2013 Regulations have enabled deposit libraries to much more comprehensively collect from what is increasingly the dominant publishing platform: the World Wide Web. The regulations ensure that the designated libraries may collect websites that are published under a UK domain (for example, .co.uk, .ac.uk, .london, .cymru, and so on) as well as any website made available to the public by a person where ‘any of that person’s activities relating to the creation or the publication of the work take place within the United Kingdom’.4 In some respects this is an even more expansive collection mandate than that afforded to print works and takes into account the increasingly (if not already entrenched) transnational nature of the Web. Additionally, as mentioned, deposit libraries are entitled under the 2013 Regulation to collect non-web-based sources of non-print publication, including e-books, electronic journals, and digital mapping.

Creativity

If any body holds and offers access to a comprehensive collection of society’s recorded knowledge (printed, electronic; old, new; artistic, technical; raw, interpreted), it is likely to be a legal deposit library. In patent terms, these institutions hold as close as possible to the complete prior art. Therefore, these collections are naturally a tremendous resource for creativity.

Using Content: Adding value

Ultimately, collections in libraries exist as the basis for future creativity. Creative work5 is built upon preceding work. You don’t reinvent the wheel. Instead, you take the power of the wheel to the next level and invent the axle and the cog. Fundamentally, creativity emerges from a coming together of existing material and novel insight: a combination of pre-existing knowledge and new ideas. As the bodies that hold the prior art, libraries are central to this cycle of creativity.

As discussed, in content terms legal deposit libraries provide unbiased access, based on unbiased collecting. Libraries are a source both of rich, interpreted material and raw, unexplored data. A library deposit can hold a well-known literary novel and an author’s extensive drafts and notes in one location: in other words, the outputs and the data. Library collections, particularly of the deposit libraries, are often centuries old. Deposit libraries, at the same time, maintain collections of highly contemporary material. In this way, libraries bring the state of the art from three centuries prior directly alongside today’s state of the art. As a source for material therefore, library collections are broad and deep, processed and raw, old and new.

Were creativity to hinge upon each individual comprehensively familiarising themselves with the complete prior art, humanity would face an impossible uphill battle that no library could address. Fortunately, this is not the case. Creativity hinges instead upon individuals coming across, finding or knowing about the right prior content at the right time. People do not need to read every book and watch every film in order to generate new ideas and develop fresh creative outputs. However, people do need access to as close to the full range of existing material as possible, since different works will prove valuable to different people at different times. This is exactly how deposit libraries act as a central resource for the creative process.

Because humanity cannot digest everything it has made previously, there need to be mechanisms for collecting, organising, storing, interpreting and promoting the prior art: teasing out the valuable material relative to particular interests, needs, uses and desires. This is a role for the library. Libraries do not simply shuffle their physical collection in and out. Instead, libraries undertake and fulfil a range of roles that serve more holistically to connect disparate sources of knowledge. An individual accessing the NLS is not, in this respect, even ‘limited’ to the millions of items housed in the Library in Edinburgh. The National Library is connected to ten thousand libraries around the world, through the WorldCat union catalogue of global collections. The British Library in London makes more than 1.6 million of its items available externally every year through inter-lending. On top of it all, NLS was entitled to collect in excess of one billion URLs during the first year that non-print legal deposit legislation was in force in the UK. All of these collections, whether in one location or linked together from numerous sites, represent a phenomenal resource for the combining of prior art and new ideas. That is, for creativity.

Capturing the Process: Future Value

As well as providing a contemporary resource to stimulate and nurture creativity, libraries serve as a particularly robust recorder of the creative process. This ability comes back to the library’s general position of being non-discriminatory in terms of the types and styles of content that it collects. Deposit libraries and research libraries in particular serve to bolster the value of their collections by gathering and maintaining valuable manuscripts, papers, diagrams, documents and other materials that creators generate in the process of their work (for example, by collecting the working papers as well as the finished novel, the working diagrams as well as the finished artwork). When institutions such as NLS gather these materials they add to the existing breadth and depth of their collections with a further layer of value, gained through the uniqueness of these materials. An institution that holds, maintains and provides access to finished items and working/process materials represents a remarkably valuable resource for future insight, and thus for creativity. This collecting allows the actual creative process, in so far as is possible, to be captured, recorded and preserved for future generations. Creativity can learn both from the existing raw materials – the prior art – and the methods and processes previously applied. Libraries collect and provide access to both.

Creativity and Copyright: The Overlap

As described, collections held by the National Library of Scotland and similar libraries are almost limitless in terms of their variety. Equally, while these institutions hold huge quantities of material, there is no realistic possibility that individuals will use all or even most of this content in creative processes. Part of a library’s role, therefore, is to provide interpretation and curated access, so that potential value may be best realised. This is where external restrictions placed upon libraries begin to become apparent. Libraries face various constraints on their operations and their ability to fulfil their primary objectives. However, restrictions on library budgets or on staff numbers are limited in their effect when compared to the restrictions that copyright legislation places upon the ability of NLS and similar bodies to step up fully to the task of adding creative value through ideal use of their collections for the generation of creativity.

The reality of this restriction becomes apparent when consideration is given not just to the potential and long-term significance of libraries to the creative process, as discussed above, but also to the real and day-to-day significance of libraries to this process. In other words, it is particularly important to consider the more particular demand for content that is placed on libraries, to consider which items library users are seeking to generate the most creativity with most often.

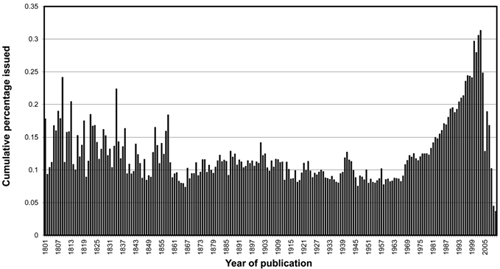

Figure 3.2 Cumulative percentage of NLS material issued

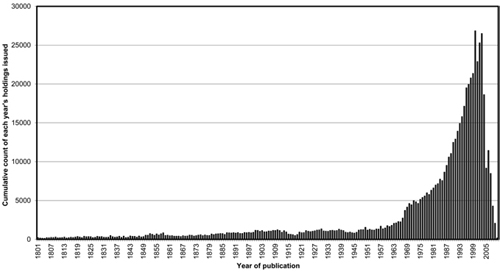

We take here the empirical example of the National Library. Up until about 1860 NLS holdings were fairly limited in number, but the books were used quite intensively. In the century from 1860 to 1960 levels of use were fairly flat, averaging about 1.5 per cent of the book stock per year. For works published before 1800, cumulative circulation from NLS remains in the tens per year. Publications from 1801 onwards see circulation jump into the low hundreds per year, and post-1900 publications have circulated in the high hundreds and low one thousands per year. Materials published in the 1960s, 70s and 80s have circulated from NLS in the two to five thousands per year, while items published in the 1990s have seen circulation jump into the tens of thousands per year of publication. Circulation of 2003 publications stand (as of 2010) at around 26,000, a considerable increase that should be considered alongside the concurrent growth in the Library’s collection size over the period 1800 to 2003 (see Figure 3.2