GENERAL DEFENCES

General defences

AIMS AND OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter you should be able to:

Understand the law on duress, necessity and marital coercion

Understand the law on duress, necessity and marital coercion

Understand the law on mistake

Understand the law on mistake

Understand the law on self-defence

Understand the law on self-defence

Understand the law on consent

Understand the law on consent

Analyse critically the scope and limitations of the general defences and the reform proposals for the general defences

Analyse critically the scope and limitations of the general defences and the reform proposals for the general defences

Apply the law to factual situations to determine whether liability can be avoided by invoking a defence

Apply the law to factual situations to determine whether liability can be avoided by invoking a defence

8.1 Duress

With this defence, D is admitting that he committed the actus reus of the offence, with mens rea, but is claiming that he did so because he was faced with threats of immediate serious injury or even death, either to himself or to others close to him, if he did not commit the offence. Duress is not a denial of mens rea, like intoxication (see Chapter 9), nor a plea that D’s act was justified, as is the case with self-defence (see below). Rather, D is seeking to be excused, because his actions were involuntary — not in the literal, physical sense of the word, but on the basis that D had no other choice. In Lynch v DPP of Northern Ireland (1975) AC 653, Lord Morris said:

JUDGMENT

‘It is proper that any rational system of law should take fully into account the standards of honest and reasonable men… If then someone is really threatened with death or serious injury unless he does what he is told is the law to pay no heed to the miserable, agonising plight of such a person? For the law to understand not only how the timid but also the stalwart may in a moment of crisis behave is not to make the law weak but to make it just.’

8.1.1 Sources of the duress

Duress comes in two types:

Duress by threats: here, D is threatened by another person to commit a criminal offence. For example, D is ordered at gunpoint to drive armed robbers away from the scene of a robbery or he will be shot.

Duress by threats: here, D is threatened by another person to commit a criminal offence. For example, D is ordered at gunpoint to drive armed robbers away from the scene of a robbery or he will be shot.

Duress of circumstances (sometimes referred to as ‘necessity’, but in this chapter necessity will be dealt with separately): here, the threat does not come from a person, but the circumstances in which D finds himself.

Duress of circumstances (sometimes referred to as ‘necessity’, but in this chapter necessity will be dealt with separately): here, the threat does not come from a person, but the circumstances in which D finds himself.

The principles applying are identical in either case of duress. The principles were originally established in duress by threat cases and subsequently applied to duress of circumstances.

8.1.2 The seriousness of the threat

The threats must be of death or serious personal injury (Hudson and Taylor (1971) 2 QB 202; Hasan (2005) UKHL 22; (2005) 2 AC 467). In A (2012) EWCA Crim 434; (2012) 2 Cr App R 8, Lord Judge CJ stated that duress ‘involves pressure which arises in extreme circumstances, the threat of death or serious injury, which for the avoidance of any misunderstanding, we have no doubt would also include rape’. Strictly speaking, this comment was obiter, because the Court of Appeal rejected A’s appeal against her conviction on the ground of lack of evidence that she had, in fact, been threatened with rape. However, it seems perfectly sensible to regard rape as an example of ‘serious personal injury’. In A, the Court of Appeal emphasised that ‘pressure’ falling short of a threat of death or serious injury did not support a plea of duress. This was designed to prevent the floodgates being opened because, as Lord Judge stated, ‘the circumstances in which different individuals are subject to pressures, or perceive that they are under pressure, are virtually infinite’.

A threat to damage or destroy property is therefore in sufficient (M’Growther (1746) Fost 13). In Lynch (1975), Lord Simon said: ‘The law must draw a line somewhere; and as a result of experience and human valuation, the law draws it between threats to property and threats to the person.’ Similarly, threats to expose a secret sexual orientation are insufficient (Singh (1974) 1 All ER 26; Valderrama-Vega (1985) Crim LR 220). In Baker and Wilkins (1996) EWCA Crim 1126; (1997) Crim LR 497, a duress of circumstances case, the Court of Appeal refused to accept an argument that the scope of the defence should be extended to cases where D believed the act was immediately necessary to avoid serious psychological injury as well as death or serious physical injury. More recently, in Dao, Mai & Nguyen (2012) EWCA Crim 1717, the Court of Appeal was asked whether a threat of false imprisonment would support a plea of duress. The Court found it unnecessary to reach a firm decision on the point — there was insufficient evidence of the appellants having been threatened with imprisonment, as they claimed — but did express a ‘provisional’ view, namely, that ‘we would have been strongly disinclined to accept that a threat of false imprisonment suffices for the defence of duress… In our judgment, even if only provisionally, policy considerations point strongly towards confining the defence of duress to threats of death or serious injury.’

Although there must be a threat of death or serious personal injury, it need not be the sole reason why D committed the offence with which he is charged. This was seen in Valderrama-Vega.

CASE EXAMPLE

Valderrama-Vega (1985) Crim LR 220

D claimed that he had imported cocaine because of death threats made by a Mafia-type organisation. But he also needed the money because he was heavily in debt to his bank. Furthermore, he had been threatened with having his homosexuality disclosed. His conviction was quashed by the Court of Appeal: the jury had been directed he only had a defence if the death threats were the sole reason for acting.

ACTIVITY

In the light of the House of Lords’ decision in Ireland, Burstow (1998) AC 147 to extend the scope of the phrase ‘bodily harm’ in the context of s 20 and s 47 OAPA 1861 to include psychiatric harm, discuss whether the Court of Appeal’s decision in Baker and Wilkins is justifiable.

8.1.3 Threats against whom?

At one time it seemed that, in cases of duress by threats, the threat had to be directed at D personally. However, in Ortiz (1986) 83 Cr App R 173, D had been forced into taking part in a cocaine-smuggling operation after he was told that, if he refused, his wife and children would ‘disappear’. At his trial, D pleaded duress by threats, but the jury rejected the defence. The trial judge had directed them that ‘duress is a defence if a man acts solely as a result of threats of death or serious injury to himself or another’. The Court of Appeal did not disapprove of the inclusion in the direction of ‘threats… to another’. The view that the threats could be directed at someone other than D was confirmed in the early duress of circumstances cases, Conway (1988) 3 All ER 1025 and Martin (1989) 1 All ER 652. In the former case, the defence was allowed when D’s passenger in his car was threatened and in the latter case D’s wife threatened to harm herself. It is now well established that the threats can be directed towards members of D’s immediate family, or indeed to ‘some other person, for whose safety D would reasonably regard himself as responsible’, according to Kennedy LJ in Wright (2000) Crim LR 510.

CASE EXAMPLE

Wright (2000) Crim LR 510

D had been arrested at Gatwick Airport with four kilos of cocaine worth nearly £1/2 million hidden under her clothing, having just flown in from St Lucia. She was charged with trying to import unlawful drugs and pleaded duress. She claimed that she had flown to St Lucia in order to bring back the drugs under threat of violence from her drug dealer, to whom she was £3, 000 in debt. In St Lucia, D was threatened with a gun and told that her boyfriend Darren (who had flown out to join her) would be killed if she did not go through with the trip; she was also told that Darren would only be allowed to return to the United Kingdom once she had reached Gatwick. This meant that when she was arrested at Gatwick, she was still fearful for Darren’s life. However, she was convicted after the trial judge directed the jury that duress was only available if a threat was directed at D herself or at a ‘member of her immediate family’. He reminded the jury that D did not live with Darren and was not married to him. D was convicted but the Court of Appeal allowed her appeal (although it ordered a retrial). Kennedy LJ said that ‘it was both unnecessary and undesirable for the judge to trouble the jury with the question of Darren’s proximity. Still less to suggest, as he did, that Darren was insufficiently proximate’. The question for the jury should simply have been whether D had good cause to fear that if she did not import the drugs, she or Darren would be killed or seriously injured.

ACTIVITY

Applying the law

1. D is accosted in his car by armed robbers who direct him to drive them away, or they will shoot randomly into a group of schoolchildren at a bus stop. Should D have a defence of duress if charged with aiding and abetting armed robbery?

2. This question was posed by Professor Sir John Smith in his commentary on Wright in the Criminal Law Review: could a fan of Manchester United be reasonably expected to resist a threat to kill the team’s star player if he did not participate in a robbery?

8.1.4 Imminence of the threat, opportunities to escape and police protection

Imminence of the threat

The threat must have been operative on D, or other parties, at the moment he committed the offence. This was established in Hudson and Taylor (1971) 2 QB 202.

CASE EXAMPLE

Hudson and Taylor (1971) 2 QB 202

D, aged 17, and E, aged 19, were the principal prosecution witnesses at the trial of a man called Jimmy Wright. He had been charged with malicious wounding. Both D and E had been in the pub where the wounding was alleged to have occurred and gave statements to the police. At the trial, however, the girls failed to identify Wright, and as a result, he was acquitted. In due course, the girls were charged with perjury (lying in court). D claimed that another man, F, who had a reputation for violence, had threatened her that if she ‘told on Wright in court’ she would be cut up. She passed this threat on to E, and the result was that they were too frightened to identify Wright (especially when they arrived in court and saw F in the public gallery). The trial judge withdrew the defence of duress from the jury because the threat of harm could not be immediately put into effect when they were testifying in the safety of the courtroom. Their convictions were quashed.

Lord Widgery CJ said:

JUDGMENT

‘When… there is no opportunity for delaying tactics and the person threatened must make up his mind whether he is to commit the criminal act or not, the existence at that moment of threats sufficient to destroy his will ought to provide him with a defence even though the threatened injury may not follow instantly but after an interval.’

JUDGMENT

‘It should be made clear to juries that if the retribution threatened against the defendant or his family or a person for whom he reasonably feels responsible is not such as he reasonably expects to follow immediately or almost immediately on his failure to comply with the threat, there may be little if any room for doubt that he could have taken evasive action, whether by going to the police or in some other way, to avoid committing the crime with which he is charged.’

The Hasan case will be examined in more detail below.

Opportunities to escape and police protection

D will be expected to take advantage of any reasonable opportunity that he has to escape from the duressor and/or contact the police. If he fails to take it, the defence may fail. This was illustrated in Gill (1963) 2 All ER 688. D claimed that he had been threatened with violence if he did not steal a lorry. The Court of Criminal Appeal expressed doubts whether the defence was open, as there was a period of time in which he could have raised the alarm and wrecked the whole enterprise. In Pommell (1995) 2 Cr App R 607, Kennedy LJ accepted that ‘in some cases a delay, especially if unexplained, may be such as to make it clear that any duress must have ceased to operate, in which case the judge would be entitled to conclude that … the defence was not open’.

CASE EXAMPLE

Pommell (1995) 2 Cr App R 607

Police found D at 8 am lying in bed with a loaded gun in his hand. He claimed that, during the night, a man called Erroll had come to see him, intent on shooting some people who had killed Erroll’s friend. D had persuaded Erroll to give him the gun, which he took upstairs. This was between 12.30 am and 1.30 am. D claimed that he had intended to hand the gun over to the police the next day. D was convicted of possessing a prohibited weapon, contrary to the Firearms Act 1968, after the trial judge refused to allow the defence of duress to go to the jury. This was on the basis that, even if D had been forced to take the gun, he should have gone immediately to the police. The Court of Appeal allowed the appeal on the basis that this was too restrictive and ordered a retrial.

In Hudson and Taylor (1971), the Crown contended that D and E should have sought police protection. Lord Widgery CJ rejected this argument, which, he said ‘would, in effect, restrict the defence… to cases where the person threatened had been kept in custody by the maker of the threats, or where the time interval between the making of the threats and the commission of the offence had made recourse to the police impossible’. Although the defence had to be kept ‘within reasonable grounds’, the Crown’s argument would impose too ‘severe’ a restriction. He concluded that ‘in deciding whether [an escape] opportunity was reasonably open to the accused the jury should have regard to his age and circumstances and to any risks to him which may be involved in the course of action relied upon’.

8.1.5 Duress does not exist in the abstract

It is only a defence if the defendant commits some specific crime which was nominated by the person making the threat. This was seen in Cole (1994) Crim LR 582, where moneylenders were pressuring D for money. They had threatened him, as well as his girlfriend and child, and hit him with a baseball bat. Eventually, D robbed two building societies. To a charge of robbery he pleaded duress, but the judge held that the defence was not available and withdrew it from the jury. D’s conviction was upheld by the Court of Appeal: the defence was only available where the threats were directed to the commission of the particular offence charged. The duressors had not said ‘Go and rob a building society or else…’.

8.1.6 Voluntary exposure to risk of compulsion

D will be denied the defence if he voluntarily places himself in such a situation that he risks being threatened with violence to commit crime. This may be because he joins a criminal organisation. In Fitzpatrick (1977) NI 20, D pleaded duress to a catalogue of offences, including murder, even though he was a voluntary member of the IRA. The trial judge rejected the defence, stating that ‘If a man chooses to expose himself and still more if he chooses to submit himself to illegal compulsion, it may not operate even in mitigation of punishment’. Any other conclusion he said ‘would surely be monstrous’. The Northern Ireland Court of Appeal dismissed the appeal. In Sharp (1987) 3 All ER 103, the Court of Appeal confirmed that duress was not available where D had voluntarily joined a ‘criminal organisation or gang’.

CASE EXAMPLE

Sharp (1987) 3 All ER 103

D and two other men had attempted an armed robbery of a sub-post office but were thwarted when the sub-postmaster pressed an alarm. As they made their escape, one of the others fired a shotgun in the air to deter pursuers. Three weeks later they carried out a second armed robbery, which resulted in the murder of the sub-postmaster. D claimed that he was only the ‘bagman’, that he was not armed and only took part in the second robbery because he had been threatened with having his head blown off by one of the others if he did not cooperate. The trial judge withdrew the defence, and D was convicted of manslaughter, robbery and attempted robbery. The Court of Appeal upheld the convictions. The Court treated it as significant that D knew of the others’ violent and trigger-happy nature several weeks before he attempted to withdraw from the enterprise.

Lord Lane CJ said:

JUDGMENT

‘Where a person has voluntarily, and with knowledge of its nature, joined a criminal organisation or gang which he knew might bring pressure on him to commit an offence and was an active member when he was put under such pressure, he cannot avail himself of the defence.’

This principle has been confirmed, and extended, in a number of subsequent cases. It is now firmly established that D does not necessarily have to have joined a criminal organisation (as in Lynch (1975) or Sharp). Voluntarily associating with persons with a propensity for violence (typically, by buying unlawful drugs from suppliers) may well be enough to deny the defence.

Ali (1995) Crim LR 303 and Baker and Ward (1999) EWCA Crim 913; (1999) 2 Cr App R 335 both concerned drug users who pleaded duress to robbery, having become indebted to their supplier and having then been threatened with violence if they did not find the money. In each case the Court of Appeal confirmed the defence would be denied in situations where D voluntarily placed himself in a position where the threat of violence was likely.

Ali (1995) Crim LR 303 and Baker and Ward (1999) EWCA Crim 913; (1999) 2 Cr App R 335 both concerned drug users who pleaded duress to robbery, having become indebted to their supplier and having then been threatened with violence if they did not find the money. In each case the Court of Appeal confirmed the defence would be denied in situations where D voluntarily placed himself in a position where the threat of violence was likely.

In Heath (1999) EWCA Crim 1526; (2000) Crim LR 109, D was a drug user who had become heavily indebted to a man with a reputation for violence and who had threatened D with violence if he did not deliver a consignment of 98 kilos of cannabis from Lincolnshire to Bristol. D was caught and charged with being in possession of cannabis. He pleaded duress, but the defence was denied and he was convicted. The Court of Appeal rejected his appeal. D had voluntarily associated himself with the drug world, knowing that in that world, debts are collected via intimidation and violence.

In Heath (1999) EWCA Crim 1526; (2000) Crim LR 109, D was a drug user who had become heavily indebted to a man with a reputation for violence and who had threatened D with violence if he did not deliver a consignment of 98 kilos of cannabis from Lincolnshire to Bristol. D was caught and charged with being in possession of cannabis. He pleaded duress, but the defence was denied and he was convicted. The Court of Appeal rejected his appeal. D had voluntarily associated himself with the drug world, knowing that in that world, debts are collected via intimidation and violence.

Harmer (2001) EWCA Crim 2930; (2002) Crim LR 401, was factually very similar to Heath. D had been caught at Dover docks trying to smuggle cocaine into the United Kingdom hidden inside a box of washing-up powder. At his trial D pleaded duress on the basis that his supplier had forced him to do it or suffer violence. D admitted that he had knowingly involved himself with criminals (he was a drug addict and had to have a supplier to get drugs) and knew that his supplier might use or threaten violence. However, he said that he had not appreciated that his supplier would demand that he get involved in crime. The defence was denied, and D was convicted; the Court of Appeal upheld his conviction, following Heath. Voluntary exposure to unlawful violence was enough to exclude the defence.

Harmer (2001) EWCA Crim 2930; (2002) Crim LR 401, was factually very similar to Heath. D had been caught at Dover docks trying to smuggle cocaine into the United Kingdom hidden inside a box of washing-up powder. At his trial D pleaded duress on the basis that his supplier had forced him to do it or suffer violence. D admitted that he had knowingly involved himself with criminals (he was a drug addict and had to have a supplier to get drugs) and knew that his supplier might use or threaten violence. However, he said that he had not appreciated that his supplier would demand that he get involved in crime. The defence was denied, and D was convicted; the Court of Appeal upheld his conviction, following Heath. Voluntary exposure to unlawful violence was enough to exclude the defence.

Professor Sir John Smith was critical of the decision in Harmer. He wrote in the commentary to the case in the Criminal Law Review that ‘the joiner may know that he may be subjected to compulsion, but compulsion to pay one’s debts is one thing, compulsion to commit crime is quite another.’ Given the judicial uncertainty and academic criticism of the law, it was perhaps inevitable that the House of Lords would eventually be asked to clarify the position regarding the availability of duress when D voluntarily associates himself with a criminal gang or organisation. In Hasan (2005) UKHL 22; (2005) 2 AC 467, the Court of Appeal had quashed D’s conviction of aggravated burglary but certified a question for the consideration of the House of Lords, seeking to establish whether the defence of duress is excluded when, as a result of the accused’s voluntary association with others

1. he foresaw (or possibly should have foreseen) the risk of being then and there subjected to any compulsion by threats of violence; or

3. only if the offences foreseen (or which should have been foreseen) were of the same type (or possibly the same type and gravity) as that ultimately committed.

The Lords reinstated D’s conviction after taking the view that option (1) above cor-rectly stated the law. By a 4:1 majority, the Lords confirmed that it was sufficient if D should have foreseen the risk of being subjected to ‘any compulsion’.

CASE EXAMPLE

Hasan (2005) UKHL 22; (2005) 2 AC 467

Z, a driver and minder for Y, a prostitute, had been threatened by Y’s boyfriend, X, who had a reputation as a violent gangster and drug dealer, to carry out a burglary. Z attempted to burgle a house, armed with a gun, but was scared off by the householder. Z was charged with aggravated burglary and pleaded duress. The trial judge directed the jury that the defence was not available if Z had voluntarily placed himself in a position in which threats of violence were likely. Z was convicted, and although the Court of Appeal quashed his conviction, it was reinstated by the House of Lords.

Lord Bingham stated:

JUDGMENT

‘The defence of duress is excluded when as a result of the accused’s voluntary association with others engaged in criminal activity he foresaw or ought reasonably to have foreseen the risk of being subjected to any compulsion by threats of violence.’

Only Baroness Hale departed from the majority: she would have preferred to take option (2). None of the five judges chose option (3). The case of Baker and Ward (1999) EWCA Crim 913, in which the Court of Appeal had decided that D had to foresee that he would be compelled to commit offences of the type with which he was charged (ie option (3)), was therefore overruled. However, the judgments in the other Court of Appeal cases, including Heath and Harmer, have now been confirmed.

Hasan was applied in Ali (2008) EWCA Crim 716, where D was charged with robbery. He had taken a Golf Turbo car on a test drive but then forced the car salesman out of the car at knifepoint before driving off. At his trial, D claimed that he had been threatened with violence by a man called Hussein if he did not commit the robbery. However, his duress defence was rejected on the basis that he had been friends with Hussein, who had a violent reputation, for many years. In the words of the trial judge, D had chosen to join ‘very bad company’. Dismissing D’s appeal, Dyson LJ stated:

JUDGMENT

‘The core question is whether [D] voluntarily put himself in the position in which he foresaw or ought reasonably to have foreseen the risk of being subjected to any compulsion by threats of violence. As a matter of fact, threats of violence will almost always be made by persons engaged in a criminal activity; but in our judgment it is the risk of being subjected to compulsion by threats of violence that must be foreseen or foreseeable that is relevant, rather than the nature of the activity in which the threatener is engaged.’

JUDGMENT

‘Common sense must recognise that there are certain kinds of criminal enterprises the joining of which, in the absence of any knowledge of propensity to violence on the part of one member, would not lead another to suspect that a decision to think better of the whole affair might lead him into serious trouble. The logic which appears to underlie the law of duress would suggest that if trouble did unexpectedly materialise and if it put the defendant into a dilemma in which a reasonable man might have chosen to act as he did, the concession to human frailty should not be denied to him.’

8.1.7 Should D have resisted the threats?

The defence is not available just because D reacted to a threat; the threat must be one that the ordinary man would not have resisted. In Graham (1982) 1 All ER 801, Lord Lane CJ laid down the following test to be applied by juries in future cases whenever duress was pleaded:

JUDGMENT

‘The correct approach on the facts of this case would have been as follows: (1) Was [D], or may he have been, impelled to act as he did because, as a result of what he reasonably believed [the duressor] had said or done, he had good cause to fear that if he did not so act [the duressor] would kill him or… cause him serious physical injury? (2) If so, have the prosecution made the jury sure that a sober person of reasonable firmness, sharing the characteristics of [D], would not have responded to whatever he reasonably believed [the duressor] said or did by taking part in the killing?’

In Howe and Bannister (1987) AC 417, the House of Lords approved the Graham test. It is clear that the same test applies (with appropriate modification to the wording to indicate the source of the threats) to duress of circumstances. The test is carefully framed in such a way to ensure the burden of proof remains on the prosecution at all times (although D must raise evidence of duress). If the jury believes that D may have been threatened and that the reasonable man might have responded to it, then they should acquit.

The first question

The first question, relating to D’s belief, is essentially (if not entirely) subjective. That is, if the jury is satisfied that D reasonably believed he faced a threat of death or serious injury and that the belief gave him ‘good cause’, then the first question is answered in D’s favour. This issue was examined by the Court of Appeal in Nethercott (2001) EWCA Crim 2535; (2002) Crim LR 402. D had been convicted of attempting to dishonestly obtain jewellery in May 1999. At his trial he had pleaded duress, relying on evidence that his co-accused, E, had stabbed him (a separate offence for which E had been charged with attempted murder) and that he therefore reasonably believed that if he did not take part in the crime, he had good cause to fear death or serious injury. The only problem for D was that the stabbing took place in August 1999 — three months after the alleged attempt. The trial judge refused to admit this evidence, and D was convicted. However, the Court of Appeal quashed his conviction. Evidence that E had stabbed D in August was relevant to the question whether, in May, he reasonably believed that E might kill or seriously injure him. It must be emphasised that there is no requirement that what D feared actually existed. This point was made clear in Cairns (1999) EWCA Crim 468; (1999) 2 Cr App R 137, a duress of circumstances case.

CASE EXAMPLE

Cairns (1999) EWCA Crim 468; (1999) 2 Cr App R 137

V, who was inebriated, stepped out in front of D’s car, forcing him to stop. V climbed onto the bonnet and spread-eagled himself on it. D drove off with V on the bonnet. A group of V’s friends ran after the car, shouting and gesticulating (they claimed later that they just wanted to stop V, not do any harm to D). D had to brake in order to drive over a speed bump, V fell off in front of the car, and was run over, suffering serious injury. D was convicted of inflicting grievous bodily harm (GBH) with intent contrary to s 18 OAPA 1861, after the trial judge ruled that the defence of duress of circumstances was only available when ‘actually necessary to avoid the evil in question’. However, the Court of Appeal quashed the conviction. It was not necessary that the threat (or, in the judge’s words, ‘evil in question’) was, in fact, real.

The principle that it is D’s belief in the existence of a threat, as opposed to its exist-ence in fact, was confirmed in Safiand others (2003).

CASE EXAMPLE

Safiand others (2003) EWCA Crim 1809

The appellants in this case had hijacked a plane in Afghanistan and ordered it to be flown to the United Kingdom, in order to escape the perceived threat of death or injury at the hands of the Taliban. (The facts of the case occurred in February 2000, ie, before the overthrow of the Taliban regime by American-led military forces in 2002.) At their trial for hijacking, false imprisonment (relating to the appellants’ failure to release the other passengers after the plane’s arrival in the United Kingdom until three days had elapsed) and other charges, the appellants pleaded duress of circumstances. This was disputed by the Crown and the jury at the first trial failed to agree. At the retrial, the trial judge told the jury to examine whether the appellants were in imminent peril (as opposed to whether they reasonably believed that they were in imminent peril). The Court of Appeal allowed the appeal and quashed the convictions. Longmore LJ suggested that, if public policy demanded the existence of an actual threat, as opposed to a reasonably perceived one, it was for Parliament to change the law.

The subjective limb as defined in Graham (1982) and approved in Howe and Bannister (1987) does have two objective aspects. First, D’s belief must have been reasonable. Thus, if D honestly (but unreasonably) believes that he is being threatened and commits an offence, the defence is not available. Hence, if D’s belief was based purely on his own imagination, it would not be difficult for a jury to conclude that his (honest) belief was unreasonable. This may be contrasted with the position in self-defence. There, if D believes he is being attacked and reacts in self-defence, he is entitled to be judged as if the facts were as he (honestly) believed them to be (Williams (1987) 3 All ER 411). One rationale for this difference could be that self-defence is a justification, while duress is ‘only’ an excuse. After a period of doubt on this point, in Hasan (2005) UKHL 22; (2005) 2 AC 467, the House of Lords confirmed that D’s belief must be reasonable. Giving the leading judgment, Lord Bingham said that ‘It is of course essential that the defendant should genuinely, that is actually, believe in the efficacy of the threat by which he claims to have been compelled. But there is no warrant for relaxing the requirement that the belief must be reasonable as well as genuine.’

A recent case demonstrates that, if D’s belief is genuine — but unreasonable — then it will not support a plea of duress.

CASE EXAMPLE

S (2012) EWCA Crim 389; (2012) 1 Cr App R 31

S was charged with abducting her own daughter, L, contrary to s 1 of the Child Abduction Act 1984. S was divorced from L’s father, but both parents shared custody. Under the terms of the divorce, neither parent was allowed to take L out of the country without the prior permission of the other parent or the High Court. In fact, S took her daughter to Spain without permission. S was tracked down in Gibraltar and ordered to return L to the United Kingdom, which she did. At her trial, S pleaded duress (of circumstances), based on her belief that there was an imminent risk of serious physical harm to L from sexual abuse from L’s father. This was rejected, and the Court of Appeal upheld the guilty verdict. Sir John Thomas said that ‘there could be no reasonable belief that a threat was imminent nor could it be said that a person was acting reasonably and proportionately by removing the child from the jurisdiction in order to avoid the threat of serious injury’.

The second objective aspect is that D’s belief must have given him ‘good cause’ to fear death or serious injury. Thus, even if D genuinely (and reasonably) believed that death or serious injury would be done to him but, objectively (ie in the opinion of the jury), death or serious injury was unlikely, then the defence fails.

The second question

This question is objective, although certain characteristics of D will be attributed to the reasonable person. In Graham (1982), Lord Lane CJ said:

JUDGMENT

‘As a matter of public policy, it seems to us essential to limit the defence of duress by means of an objective criterion formulated in terms of reasonableness … The law [of provocation] requires a defendant to have the self-control reasonably to be expected of the ordinary citizen in his situation. It should likewise require him to have the steadfastness reasonably to be expected of the ordinary citizen in his situation.’

Thus, if the ordinary person, sharing the characteristics of D, would have resisted the threats, the defence is unavailable. The relevant characteristics will include age and sex and, potentially at least, other permanent physical and mental attributes which would affect the ability of D to resist pressure and threats. In Hegarty (1994) Crim LR 353, however, the Court of Appeal held that the trial judge had correctly refused to allow D’s characteristic of being in a ‘grossly elevated neurotic state’, which made him vulnerable to threats, to be considered as relevant. Similarly, in Horne (1994) Crim LR 584, the Court of Appeal agreed that evidence that D was unusually pliable and vulnerable to pressure did not mean that these characteristics had to be attrib-uted to the reasonable man. In Bowen (1996) Crim LR 577, the Court of Appeal said that the following characteristics were obviously relevant:

Age, as a young person may not be so robust as a mature one.

Age, as a young person may not be so robust as a mature one.

Pregnancy, where there was an added fear for the unborn child.

Pregnancy, where there was an added fear for the unborn child.

Serious physical disability, as that might inhibit self-protection.

Serious physical disability, as that might inhibit self-protection.

Recognised mental illness or psychiatric condition, such as post-traumatic stress disorder leading to learnt helplessness. Psychiatric evidence might be admissible to show that D was suffering from such condition, provided persons generally suffering them might be more susceptible to pressure and threats. It was not admissible simply to show that in a doctor’s opinion D, not suffering from such illness or condition, was especially timid, suggestible or vulnerable to pressure and threats.

Recognised mental illness or psychiatric condition, such as post-traumatic stress disorder leading to learnt helplessness. Psychiatric evidence might be admissible to show that D was suffering from such condition, provided persons generally suffering them might be more susceptible to pressure and threats. It was not admissible simply to show that in a doctor’s opinion D, not suffering from such illness or condition, was especially timid, suggestible or vulnerable to pressure and threats.

Finally, D’s gender might possibly be relevant, although the court thought that many women might consider that they had as much moral courage to resist pressure as men. The Court of Appeal dismissed D’s appeal holding that a low IQ — falling short of mental impairment or mental defectiveness — could not be said to be a characteristic that made those who had it less courageous and less able to withstand threats and pressure. The decision in Bowen to allow evidence of post-traumatic stress disorder leading to learnt helplessness as a characteristic is interesting, and not particularly easy to reconcile with the earlier decisions of Hegarty and Horne. A jury faced with the question, ‘Would the ordinary person, displaying the firmness reasonably to be expected of a person of the defendant’s age and sex suffering from learnt helplessness have yielded to the threat?’ is almost certain to answer in the affirmative, except if the threat was very trivial indeed.

8.1.8 The scope of the defence

Duress (either by threats or circumstances or both) has been accepted as a defence to manslaughter (Evans and Gardiner (1976) VR 517, an Australian case); causing GBH with intent (Cairns (1999)); criminal damage (Crutchley (1831) 5 C & P 133); theft (Gill (1963)); handling stolen goods (Attorney-General v Whelan (1934) IR 518) and obtaining property by deception (Bowen (1996)). It has also been accepted as a defence to the following: perjury (Hudson and Taylor (1971)); drug offences (Valderrama-Vega (1985)); firearms offences (Pommell (1995)); driving offences (Willer (1986) 83 Cr App R 225;Conway (1988); Martin (1989) 1 All ER 652); hijacking (Abdul-Hussain (1999); Safiand others (2003)); kidnapping (Safiand others) and breach of the Official Secrets Act (Shayler (2001) EWCA Crim 1977; (2001) 1 WLR 2206: see below). Indeed, it seems that duress (both forms) will be accepted as a defence to any crime except murder and attempted murder (and possibly some forms of treason).

Murder

The case of Dudley and Stephens (1884) 14 QBD 273 is often cited as authority for the proposition that necessity is not a defence to murder (a view not accepted by the Court of Appeal (Civil Division) in Re A (Children) (Conjoined Twins: Surgical Separation) (2000) EWCA Civ 254; (2000) 4 All ER 961, a case which will be discussed

in section 8.2). Dudley and Stephens was, however, relied upon by Lords Hailsham, Griffiths and Mackay in Howe and Bannister (1987) as authority for the proposition that the defence of duress by threats was also unavailable to those charged with murder.

CASE EXAMPLE

Dudley and Stephens (1884) 14 QBD 273

D and S had been shipwrecked in a boat with another man and a cabin boy. After several days without food or water, they decided to kill and eat the boy, who was the weakest of the four. Four days later they were rescued. On the murder trial, the jury returned a special verdict, finding that they would have died had they not eaten the boy (although there was no greater necessity for killing the boy than anyone else). Lord Coleridge CJ agreed with the last point, adding that as the mariners were adrift on the high sea, killing any one of them was not going to guarantee their safety, and thus it could be argued that it was not necessary to kill anyone. D and S were sentenced to hang, but this was commuted to six months imprisonment after Queen Victoria intervened and exercised the Royal Prerogative.

In Howe and Bannister, the Lords gave various reasons for withdrawing the defence of duress by threats from those charged with murder.

The ordinary man of reasonable fortitude, if asked to take an innocent life, might be expected to sacrifice his own. Lord Hailsham could not ‘regard a law as either “just” or “humane” which withdraws the protection of the criminal law from the innocent victim, and casts the cloak of protection on the cowards and the poltroon in the name of a concession to human frailty’.

The ordinary man of reasonable fortitude, if asked to take an innocent life, might be expected to sacrifice his own. Lord Hailsham could not ‘regard a law as either “just” or “humane” which withdraws the protection of the criminal law from the innocent victim, and casts the cloak of protection on the cowards and the poltroon in the name of a concession to human frailty’.

ACTIVITY

Self-test question

Discuss whether the law should require heroism. Refer back to Lord Lane’s test in Graham (approved in Howe and Bannister) which sets a standard of the ‘sober person of reason-able firmness’. If the reasonable man would have killed in the same circumstances, why should D be punished — with a life sentence for murder — when he only did what anyone else would have done?

One who takes the life of an innocent cannot claim that he is choosing the lesser of two evils (per Lord Hailsham).

One who takes the life of an innocent cannot claim that he is choosing the lesser of two evils (per Lord Hailsham).

This may be true if D alone is threatened; but what if D is told to kill V and that if he does not, a bomb will explode in the middle of a crowded shopping centre? Surely that is the lesser of two evils? The situation where D’s family are threatened with death if D does not kill a third party is far from uncommon.

The Law Commission (LC) recommended in 1977 that duress be a defence to murder. That recommendation was not implemented; this suggested that Parliament was happy with the law as it was.

The Law Commission (LC) recommended in 1977 that duress be a defence to murder. That recommendation was not implemented; this suggested that Parliament was happy with the law as it was.

Parliament’s lack of legislative activity in various aspects of criminal law, despite numerous promptings from the LC and others, is notorious (eg failure to reform non-fatal offences, discussed in Chapter 11). So its failure to adopt one LC proposal should not be taken to indicate Parliament’s satisfaction instead of its intransigence.

But D still faces being branded as, in law, a ‘murderer’, and a morally innocent man should not have to rely on an administrative decision for his freedom.

To recognise the defence would involve overruling Dudley and Stephens. According to Lord Griffiths, the decision was based on ‘the special sanctity that the law attaches to human life and which denies to a man the right to take an innocent life even at the price of his own or another’s life’.

To recognise the defence would involve overruling Dudley and Stephens. According to Lord Griffiths, the decision was based on ‘the special sanctity that the law attaches to human life and which denies to a man the right to take an innocent life even at the price of his own or another’s life’.

The basis of the decision in Dudley and Stephens is in fact far from clear. It would be possible to recognise a defence of necessity to murder without overruling Dudley and Stephens.

Lord Griffiths thought the defence should not be available because it was ‘so easy to raise and may be difficult for the prosecution to disprove’.

Lord Griffiths thought the defence should not be available because it was ‘so easy to raise and may be difficult for the prosecution to disprove’.

This argument applies to most defences! It also ignores the fact that in Howe and Bannister itself, the jury had rejected the defence and convicted. Indeed, Lord Hailsham said that ‘juries have been commendably robust’ in rejecting the defence on other cases.

Lord Bridge thought that it was for Parliament to decide the limits of the defence.

Lord Bridge thought that it was for Parliament to decide the limits of the defence.

Why should this be? Duress is a common law defence, so the judges should decide its scope.

CASE EXAMPLE

Howe and Bannister (1987) AC 417

D, aged 19, and E, aged 20, together with two other men, one aged 19, and the other, Murray, aged 35, participated in the torture, assault, and then strangling of two young male victims at a remote spot on the Derbyshire moors. At their trial on two counts of murder and one of conspiracy to murder, they pleaded duress, arguing that they feared for their lives if they did not do as Murray directed. He was not only much older than the others but had appeared in court several times before and had convictions for violence. D and E were convicted of all charges, and their appeals failed in the Court of Appeal and House of Lords.

Howe and Banister was followed in Wilson (2007) EWCA Crim 1251; (2007) 2 Cr. App. R. 31, where the Court of Appeal confirmed that duress was never a defence to murder, even though D was a 13-year-old boy. D and his father E murdered E’s neighbour, V, using various weapons. At trial, D pleaded duress, on the basis that E had threatened him with violence if he did not participate. The defence was rejected. Lord Phillips CJ stated:

JUDGMENT

‘There may be grounds for criticising a principle of law that does not afford a 13-year-old boy any defence to a charge of murder on the ground that he was complying with his father’s instructions, which he was too frightened to refuse to disobey. But our criminal law holds that a 13-year-old boy is responsible for his actions and the rule that duress provides no defence to a charge of murder applies however susceptible D may be to the duress.’

First, duress would, in principle, have been available (Cairns (1999)).

First, duress would, in principle, have been available (Cairns (1999)).

Second, the Graham/Bowen test would have applied. The jury would have been asked to decide (1) whether D may have been impelled to act as he did because, as a result of what he reasonably believed E had said or done, he had good cause to fear that if he did not so act E would kill or seriously injure him; (2) whether a sober 13-year-old boy of reasonable firmness might have taken part in the attack.

Second, the Graham/Bowen test would have applied. The jury would have been asked to decide (1) whether D may have been impelled to act as he did because, as a result of what he reasonably believed E had said or done, he had good cause to fear that if he did not so act E would kill or seriously injure him; (2) whether a sober 13-year-old boy of reasonable firmness might have taken part in the attack.

Duress and attempted murder

In Howe and Bannister, Lord Griffiths said, obiter, that the defence of duress was not available to charges of attempted murder. This was confirmed in Gotts (1991) 2 All ER 1, where Lord Jauncey said that he could ‘see no justification in logic, morality or law in affording to an attempted murderer the defence which is withheld from a murderer’.

CASE EXAMPLE

Gotts (1991) 2 All ER 1

D, aged 16, had been threatened with death by his father unless he tracked his mother down to a refuge and killed her. D did as directed but, although seriously injured, his mother survived. The trial judge withdrew the defence and D was convicted. The Court of Appeal and House of Lords upheld his conviction.

ACTIVITY

Self-test question

D1, with intent to do serious harm, attacks and kills V. He appears to be guilty of mur-der and would have no defence of duress to murder (Howe and Bannister (1987)) and would face life imprisonment. D2, with intent to do serious harm, attacks V and causes serious injury but not death. He could plead duress to a charge under s 18 OAPA 1861 (Cairns (1999)) and, if successful, would receive an acquittal. (D2 could not be convicted of attempted murder because this requires proof of intent to kill.) D1 and D2 have the same mens rea, but one is labelled a murderer and faces a long prison term; the other escapes with no punishment at all. Is this justifiable? Bear in mind that the difference between the two cases is simply whether V survives, which is subject to a number of variables (V’s age and state of health, the quality of medical treatment available, etc).

Reform

In its 2005 Consultation Paper, A New Homicide Act? the LC suggested that duress should be made available as a partial defence to murder. However, by the time of their 2006 Report, Murder, Manslaughter and Infanticide, the LC had changed their position and instead recommended that duress should be a full defence to both murder and attempted murder. This would entail abolishing the principles established by the House of Lords in Howe and Banister (1987) and Gotts (1991). It remains to be seen whether the government, and Parliament, will support the LC. The Ministry of Justice Consultation Paper, Murder, Manslaughter and Infanticide: Proposals for Reform of the Law (July 2008), made no reference to these proposals.

8.1.9 The development of duress of circumstances

Duress of circumstances has really only received official recognition from the appel-late courts in the last 25 years. The first cases all, coincidentally, involved driving offences.

Willer (1986). D was forced to drive his car on the pavement in order to escape a gang of youths who were intent on attacking him and his passenger. The Court of Appeal allowed D’s appeal against a conviction for reckless driving, on the basis of duress of circumstances. Watkins LJ said that D was ‘wholly driven by force of circumstance into doing what he did and did not drive the car otherwise than under that form of compulsion, ie under duress.’

Willer (1986). D was forced to drive his car on the pavement in order to escape a gang of youths who were intent on attacking him and his passenger. The Court of Appeal allowed D’s appeal against a conviction for reckless driving, on the basis of duress of circumstances. Watkins LJ said that D was ‘wholly driven by force of circumstance into doing what he did and did not drive the car otherwise than under that form of compulsion, ie under duress.’

Conway (1988). D again successfully appealed against a conviction for reckless driving. He had driven his car at high speed to escape what he thought were two men intent on attacking his passenger (in fact they were police officers).

Conway (1988). D again successfully appealed against a conviction for reckless driving. He had driven his car at high speed to escape what he thought were two men intent on attacking his passenger (in fact they were police officers).

Martin (1989). D’s conviction for driving while disqualified was quashed. He had only driven his car after his wife became hysterical and threatened to kill herself if D did not drive his stepson to work.

Martin (1989). D’s conviction for driving while disqualified was quashed. He had only driven his car after his wife became hysterical and threatened to kill herself if D did not drive his stepson to work.

DPP v Bell (1992) Crim LR 176. D’s conviction for driving with excess alcohol was quashed. He had only got into his car and driven it (a relatively short distance) in order to escape a gang who were pursuing him.

DPP v Bell (1992) Crim LR 176. D’s conviction for driving with excess alcohol was quashed. He had only got into his car and driven it (a relatively short distance) in order to escape a gang who were pursuing him.

DPP v Davis; DPP v Pittaway (1994) Crim LR 600. Both appellants had convictions for driving with excess alcohol quashed on the basis that they had only driven to escape perceived violence from other people.

DPP v Davis; DPP v Pittaway (1994) Crim LR 600. Both appellants had convictions for driving with excess alcohol quashed on the basis that they had only driven to escape perceived violence from other people.

In Conway, Woolf LJ (as he then was) spelled out the ingredients of the new defence as follows:

JUDGMENT

‘Necessity can only be a defence… where the facts establish “duress of circum-stances”, that is, where [D] was constrained to act by circumstances to drive as he did to avoid death or serious bodily injury to himself or some other person … This approach does no more than recognise that duress is an example of necessity. Whether “duress of circumstances” is called “duress” or “necessity” does not matter. What is important is that it is subject to the same limitations as the “do this or else” species of duress.’

In Martin (1989), Simon Brown J said that English law did ‘in extreme circumstances recognise a defence of necessity. Most commonly this defence arises as duress [by threats]. Equally however it can arise from other objective dangers threatening the accused or others. Arising thus it is conveniently called “duress of circumstances”.’ For a time there was a perception that duress of circumstances might be limited to driving offences, but in Pommell (1995), the Court of Appeal confirmed that the defence was of general application. It has subsequently been pleaded (not necessarily successfully) in cases of hijacking (Abdul-Hussain (1999), Safiand others (2003)) and breach of the Official Secrets Act 1989 (Shayler (2001)).

Duress of circumstances and necessity: are they the same thing?

You will have noted that in several of the above cases the courts have tended to describe duress of circumstances and necessity as the same thing. You are referred in particular to Lord Woolf’s comments in Conway (1988) and more recently in Shayler (2001). In the latter case D, a former member of the British Security Service (MI5), was charged (and ultimately convicted of) disclosing confidential documents in breach of the Official Secrets Act 1989. Unusually, his defence (whether it is properly regarded as duress of circumstances or necessity is perhaps a moot point) was considered both by the Court of Appeal and by the House of Lords before the actual trial. Lord Woolf CJ, giving judgment in the Court of Appeal, gave a very strong indication that duress of circumstances and necessity were interchangeable. He stated:

JUDGMENT

‘The distinction between duress of circumstances and necessity has, correctly, been by i and large ignored or blurred by the courts. Apart from some of the medical cases like Re F (1990) 2 AC 1, the law has tended to treat duress of circumstances and necessity as one and the same.’

However, in this book they will be regarded as separate defences. There are two reasons for this.

It is clear that duress, whether by threats or of circumstances, cannot be a defence to murder (or attempted murder). However, according to the case of Re A (Children) (Conjoined Twins) (2000), discussed in section 8.2, ‘necessity’ may be a defence to murder.

It is clear that duress, whether by threats or of circumstances, cannot be a defence to murder (or attempted murder). However, according to the case of Re A (Children) (Conjoined Twins) (2000), discussed in section 8.2, ‘necessity’ may be a defence to murder.

Duress (again whether by threats or of circumstances) exists only where D or someone he is responsible for is in immediate danger of death or serious injury. This is not necessarily the case in necessity, a point for which Re A is again authority.

Duress (again whether by threats or of circumstances) exists only where D or someone he is responsible for is in immediate danger of death or serious injury. This is not necessarily the case in necessity, a point for which Re A is again authority.

KEY FACTS

Key facts on duress

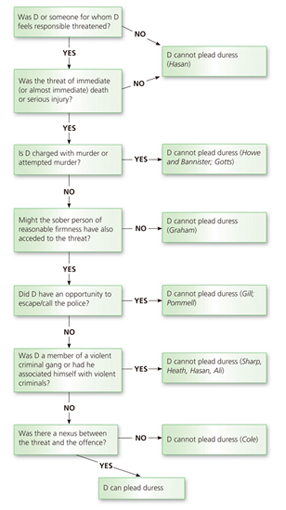

| Elements | Comment | Cases |

| Source of duress | By threats By circumstances | Lynch (1975) Willer (1986), Conway (1988), Martin (1989) |

| Degree of duress | Threat or danger posed must be of death orserious personal injury (including rape). This means physical injury not psychological injury. Threat of exposure of secret sexual orientation insufficient | Hasan (2005), A (2012) Baker and Wilkins (1997) Valderrama-Vega (1985) |

| Duress against whom? | Usually D personally Also includes duress against family Even persons for whom defendant reasonably feels responsible | Graham (1982), Cairns (1999) Ortiz (1986), Conway (1988), Martin (1989) Wright (2000) |

| Imminence | Threat or danger must be believed to be immediate or almost immediate. Defendant should alert police as soon as possible; delay in doing so does not necessarily mean defence fails. | Hasan (2005) Gill (1963), Pommell (1995) |

| Association with crime | Voluntarily joining a violent criminal gang means defendant may not have the defence. Voluntary association with violent criminals has the same effect. Voluntarily joining a violent criminal gang means defendant may not have the defence. Voluntary association with violent criminals has the same effect. | Fitzpatrick (1977), Sharp (1987) Ali (1995), Baker and Ward (1999), Heath (2000) Shepherd |