INTRODUCTION TO CRIMINAL LAW

Introduction to criminal law

AIMS AND OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter you should be able to:

Understand the basic origins and purposes of criminal law

Understand the basic origins and purposes of criminal law

Understand the definitions and classifications of criminal law

Understand the definitions and classifications of criminal law

Understand the basic workings of the criminal justice system

Understand the basic workings of the criminal justice system

Understand the basic concept of the elements of actus reus and mens rea in criminal law

Understand the basic concept of the elements of actus reus and mens rea in criminal law

Understand the burden and standard of proof in criminal cases

Understand the burden and standard of proof in criminal cases

Understand how human rights law may have an effect on criminal law

Understand how human rights law may have an effect on criminal law

This book deals with substantive criminal law. Substantive criminal law refers to the physical and mental element (if any) that has to be proved for each criminal offence. It also includes the general principles of intention and causation, the defences available and other general rules such as those on when participation in a crime makes the person criminally liable. Substantive criminal law does not include rules of procedure or evidence or sentencing theory and practice. However, these are equally important parts of the criminal justice system.

This chapter, therefore, gives some background information on criminal law. The purpose of the criminal law is considered, as well as how we know what is recognised as a crime, and the sources of criminal law. There are also brief sections explaining the courts in which criminal offences are tried, and the purposes of sentencing. The penultimate section of this chapter explains the burden and standard of proof in criminal cases. The final section looks at the effect of human rights law on criminal law.

1.1 Purpose of criminal law

The purpose of criminal law has never been written down by Parliament and, as the criminal law has developed over hundreds of years, it is difficult to state the aims in any precise way. However, there is general agreement that the main purposes are to:

protect individuals and their property from harm

protect individuals and their property from harm

preserve order in society

preserve order in society

punish those who deserve punishment

punish those who deserve punishment

However, on this last point, it should be noted that there are also other aims when a sentence is passed on an offender. These include incapacitation, deterrence, reformation and reparation.

In addition to the three main aims of the criminal law listed above, there are other points which have been put forward as purposes. These include:

educating people about appropriate conduct and behaviour

educating people about appropriate conduct and behaviour

enforcing moral values

enforcing moral values

The use of the law in educating people about appropriate conduct can be seen in the drink-driving laws. The conduct of those whose level of alcohol in their blood or urine was above specified limits has only been criminalised since 1967. Prior to that, it had to be shown that a driver was unfit to drive as a result of drinking. Since 1967, there has been a change in the way that the public regard drink-driving. It is now much more unacceptable, and the main reason for this change is the increased awareness, through the use of television adverts, of people about the risks to innocent victims when a vehicle is driven by someone over the legal limit.

1.1.1 Should the law enforce moral values?

This is more controversial, and there has been considerable debate about whether the law should be used to enforce moral values. It can be argued that it is not the function of criminal law to interfere in the private lives of citizens unless it is necessary to try to impose certain standards of behaviour. The Wolfenden Committee reporting on homosexual offences and prostitution (1957) felt that intervention in private lives should only occur in order to:

preserve public order and decency

preserve public order and decency

protect the citizen from what is offensive or injurious

protect the citizen from what is offensive or injurious

provide sufficient safeguards against exploitation and corruption of others, particularly those who are especially vulnerable

provide sufficient safeguards against exploitation and corruption of others, particularly those who are especially vulnerable

Lord Devlin disagreed. He felt that ‘there are acts so gross and outrageous that they must be prevented at any cost’. He set out how he thought it should be decided what type of behaviour be viewed as criminal by saying:

QUOTATION

How are the moral judgments of society to be ascertained … It is surely not enough that they should be reached by the opinion of the majority; it would be too much to require the individual assent of every citizen. English law has evolved and regularly uses a standard which does not depend on the counting of heads. It is that of the reasonable man. He is not to be confused with the rational man. He is not to be expected to reason about anything and his judgment may be largely a matter of feeling … for my purpose I should like to call him the man in the jury box …

Lord Devlin, The Enforcement of Morals (Oxford University Press, 1965)

There are two major problems with this approach. First, the decision of what moral behaviour is criminally wrong is left to each jury to determine. This may lead to inconsistent results, as there is a different jury for each case. Second, Lord Devlin is content to rely on what may be termed ‘gut reaction’ to decide if the ‘bounds of toleration are being reached’. This is certainly not a legal method nor a reliable method of deciding what behaviour should be termed criminal. Another problem with Lord Devlin’s approach is that society’s view of certain behaviour changes over a period of time. Perhaps because of the lack of agreement on what should be termed ‘criminal’ and the difficulty of finding a satisfactory way of legally defining such behaviour, there is another problem in that the courts do not approach certain moral problems in a consistent way. This can be illustrated by conflicting cases on when the consent of the injured party can be a defence to a charge of assault. The first is the case of Brown (1993) 2 All ER 75.

CASE EXAMPLE

Brown (1993) 2 AII ER 75

Several men in a group of consenting adult sado-masochists were convicted of assault causing actual bodily harm (s 47 Offences Against the Person Act 1861) and malicious wounding (s 20 Offences Against the Person Act 1861). They had carried out in private such acts as whipping and caning, branding, applying stinging nettles to the genital area and inserting map pins or fish hooks into the penises of each other. All of the men who took part consented to the acts against them. There was no permanent injury to any of the men involved and no evidence that any of them had needed any medical treatment. The House of Lords considered whether consent should be available as a defence in these circumstances. It took the view that it could not be a defence and upheld the convictions.

Lord Templeman said:

JUDGMENT

‘The question whether the defence of consent should be extended to the consequences of sado-masochistic encounters can only be decided by consideration of policy and public interest … Society is entitled and bound to protect itself against a cult of violence. Pleasure derived from the infliction of pain is an evil thing. Cruelty is uncivilised.’

Two of the judges dissented and would have allowed the appeals. One of these judges, Lord Slynn, expressed his view by saying:

JUDGMENT

‘Adults can consent to acts done in private which do not result in serious bodily harm, so that such acts do not constitute criminal assaults for the purposes of the 1861 [Offences Against the Person] Act. In the end it is a matter of policy in an area where social and moral factors are extremely important and where attitudes could change. It is a matter of policy for the legislature to decide. It is not for the courts in the interests of paternalism or in order to protect people from themselves to introduce into existing statutory crimes relating to offences against the person, concepts which do not properly fit there.’

The second case is Wilson (1996) Crim LR 573, where a husband had used a heated butter knife to brand his initials on his wife’s buttocks, at her request. The wife’s burns had become infected and she needed medical treatment. He was convicted of assault causing actual bodily harm (s 47 Offences Against the Person Act 1861) but on appeal the Court of Appeal quashed the conviction. Russell LJ said:

JUDGMENT

‘[W]e are firmly of the opinion that it is not in the public interest that activities such as the appellant’s in this appeal should amount to a criminal behaviour. Consensual activity between husband and wife, in the privacy of the matrimonial home, is not, in our judgment, a proper matter for criminal investigation, let alone criminal prosecution. In this field, in our judgment, the law should develop upon a case by case basis rather than upon general propositions to which, in the changing times we live, exceptions may arise from time to time not expressly covered by authority.’

The similarities in the two cases are that both activities were in private and the participants were adults. In Brown there were no lasting injuries and no evidence of the need for medical treatment, whereas in Wilson the injuries were severe enough for Mrs Wilson to seek medical attention (and for the doctor to report the matter to the police). The main distinction which the courts relied on was that in Brown the acts were for sexual gratification, whereas the motive in Wilson was of ‘personal adornment’. Is this enough to label the behaviour in Brown as criminal? (See sections 8.9.3 and 8.9.4 for further discussion of the decision in Brown and also the decision of the European Court of Human Rights in the case.)

The reference in Russell LJ’s judgment to changing times acknowledges that soci-ety’s view of some behaviour can change. There can also be disagreement about what morals should be enforced. Abortion was legalised in 1967, yet some people still believe it is morally wrong. A limited form of euthanasia has been accepted as legal with the ruling in Airedale NHS Trust v Bland (1993) 1 All ER 821, where it was ruled that medical staff could withdraw life support systems from a patient, who could breathe unaided but was in a persistent vegetative state. This ruling meant that they could withdraw the feeding tubes of the patient, despite the fact that this would inevitably cause him to die. Many people believe that this is immoral, as it denies the sanctity of human life.

All these matters show the difficulty of agreeing that one of the purposes of criminal law should be to enforce moral standards.

1.1.2 Example of the changing nature of criminal law

As moral values will have an effect on the law, what conduct is criminal may, therefore, vary over time and from one country to another. The law is likely to change when there is a change in the values of government and society. A good example of how views on what is criminal behaviour change over time can be seen from the way the law on consensual homosexual acts has changed.

The Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885 criminalised consensual homosexual acts between adults in private. It was under this law that the playwright Oscar Wilde was imprisoned in 1895.

The Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885 criminalised consensual homosexual acts between adults in private. It was under this law that the playwright Oscar Wilde was imprisoned in 1895.

The Sexual Offences Act 1967 decriminalised such behaviour between those aged 21 and over.

The Sexual Offences Act 1967 decriminalised such behaviour between those aged 21 and over.

The Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994 decriminalised such behaviour for those aged 18 and over.

The Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994 decriminalised such behaviour for those aged 18 and over.

In 2000 the Government reduced the age of consent for homosexual acts to 16, though the Parliament Acts had to be used as the House of Lords voted against the change in the law.

In 2000 the Government reduced the age of consent for homosexual acts to 16, though the Parliament Acts had to be used as the House of Lords voted against the change in the law.

We will now move on to consider where the criminal law comes from.

1.2 Sources of criminal law

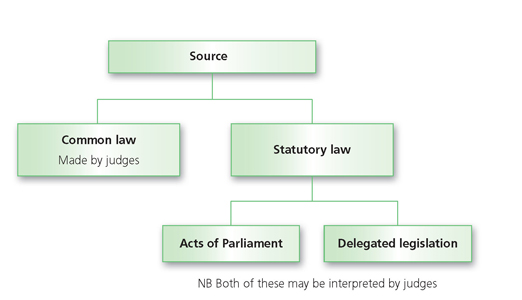

The two main areas from which our criminal law is derived are case decisions (common law) and Acts of Parliament.

1.2.1 Common law offences

The courts have developed the criminal law in decisions over hundreds of years. In o some instances offences have been entirely created by case law and precedents set by judges in those cases. An offence which is not defined in any Act of Parliament or delegated legislation is called a common law offence. Murder is such an offence. The classic definition of murder comes from the seventeenth-century jurist, Lord A Coke. This definition has continually been refined by judges, including some important decisions during the 1980s and 1990s. Other common law offences include manslaughter and assault and battery. Equally, some defences have been entirely created by the decisions of judges. The defences of duress, duress of circumstances, automatism and intoxication all come into this category.

One problem with common law offences is that they can be very vague. This is illustrated by the common law offence of outraging public decency. This offence has arisen so rarely that there have even been debates about whether it actually exists, but it was used in two separate cases in the 1990s. The first case was Gibson and another (1991) 1 All ER 439.

CASE EXAMPLE

Gibson and another (1991) 1 All ER 439

In this the first defendant had created an exhibit of a model’s head with earrings which were made out of freeze-dried real human foetuses. He intended to convey the message that women wear their abortions as lightly as they wear earrings. This model was put on public display in the second defendant’s art gallery. Both men were convicted of outraging public decency and their convictions were upheld by the Court of Appeal.

The second case was very different. This was Walker (1995) Crim LR 44, where the defendant had exposed his penis to two girls in the sitting room of his own house. The Court of Appeal allowed the defendant’s appeal against his conviction, as the place where the act occurred was not open to the public. The prosecution’s choice of charge seems odd, but presumably the fact that there had been very few cases made it difficult for them to know whether it was necessary to prove only that other people had been outraged or whether, as decided by the Court of Appeal, it had to be in a place where there was a real possibility that members of the general public might witness the act. In fact in Walker there were other more suitable offences with which the defendant could have been charged.

In some instances the courts will develop the law and then it will be absorbed into a statute. This happened with the defence of provocation (a defence to murder). It had been developed through case law but was then set out in the Homicide Act 1957. Even where there is a definition in an Act of Parliament, the courts may still have a role to play in interpreting that definition and drawing precise boundaries for the crime.

1.2.2 Statutory offences

Today the majority of offences are set out in an Act of Parliament or through delegated legislation. About 70 to 80 Acts of Parliament are passed each year. In addition there is a considerable amount of delegated legislation each year, including over 3, 000 statutory instruments created by Government Ministers.

Most offences today are statutory ones. Examples include theft, robbery and burglary which are in the Theft Act 1968. Criminal damage is set out in the Criminal Damage Act 1971. The law on sexual offences is now largely contained in the Sexual Offences Act 2003. The various offences of fraud are set out in the Fraud Act 2006.

Note that, even when offences have been created by Acts of Parliament or delegated legislation, judges still play a role in interpretation. Different sources of law are shown in Figure 1.1.

1.2.3 Codification of the criminal law

One of the main problems in criminal law is that it has developed in a piecemeal way and it is difficult to find all the relevant law. Some of the most important concepts, such as the meaning of ‘intention’, still come from case law and have never been defined in an Act of Parliament. Other areas of the law rely on old Acts of Parliament, such as the Offences Against the Person Act which is nearly 150 years old. All these factors mean that the law is not always clear. In 1965 the Government created a full-time law reform body called the Law Commission. The Law Commission has the duty to review all areas of law, not just the criminal law. By s 3(1) of the Law Commissions Act 1965 the Commission was established to:

SECTION

‘… take and keep under review all the law. with a view to its systematic development and reform, including in particular the codification of such law, the elimination of anomalies, the repeal of obsolete and unnecessary enactments, the reduction of the number of separate enactments and generally the simplification and modernisation of the law’.

The Law Commission decided to attempt the codification of the criminal law to include existing law and to introduce reforms to key areas. A first draft was produced in 1985, and this was followed by consultation which led to the publication of A Criminal Code for England and Wales (1989) (Law Com No 177).

The two main purposes of the code were regarded as:

bringing together in one place most of the important offences

bringing together in one place most of the important offences

establishing definitions of key fault terms such as ‘intention’ and ‘recklessness’

establishing definitions of key fault terms such as ‘intention’ and ‘recklessness’

The second point would also have helped Parliament in the creation of any new offences as it would be presumed that, when using words defined by the code in a new offence, it intended the meanings given by the criminal code unless they specifically stated otherwise.

The Draft Criminal Code has never been made law. Parliament has not had either the time or the will for such a large-scale technical amendment to the law. Because of this the Law Commission has since 1989 tried what may be called a ‘building-block’ approach, under which it has produced reports and draft Bills on small areas of law in the hope that Parliament would at least deal with the areas most in need of reform.

In its Tenth Programme in 2008 the Law Commission removed the codification of criminal law from its law reform programme. It stated that it continued to support the objective of codifying the law and would continue to codify where it could. However, it considered that it needs to redefine its approach and intends to simplify areas of the criminal law as a step towards codification.

Past Law Commission reports for reform of the criminal law have included:

Legislating the Criminal Code: Offences Against the Person and General Principles (1993) Law Com No 218

Legislating the Criminal Code: Offences Against the Person and General Principles (1993) Law Com No 218

Legislating the Criminal Code: Intoxication and Criminal Liability (1995) Law Com No 229

Legislating the Criminal Code: Intoxication and Criminal Liability (1995) Law Com No 229

Legislating the Criminal Code: Involuntary Manslaughter (1996) Law Com No 237

Legislating the Criminal Code: Involuntary Manslaughter (1996) Law Com No 237

Fraud (2002) Law Com No 276

Fraud (2002) Law Com No 276

Inchoate Liability for Assisting and Encouraging Crime (2006) Law Com No 300

Inchoate Liability for Assisting and Encouraging Crime (2006) Law Com No 300

Murder, Manslaughter and Infanticide (2006) Law Com No 304

Murder, Manslaughter and Infanticide (2006) Law Com No 304

Participating in Crime (2007) Law Com No 305

Participating in Crime (2007) Law Com No 305

Intoxication and Criminal Liability (2009) Law Com No 314

Intoxication and Criminal Liability (2009) Law Com No 314

Conspiracy and Attempts (2009) Law Com No 318

Conspiracy and Attempts (2009) Law Com No 318

These reports deal with areas of law in which cases have highlighted problems. Although these are areas of law where reform is clearly needed, Parliament has been slow to enact the Law Commission’s reports on reform of specific areas of criminal law. For example there has been no reform of the law on offences against the person or on the defence of intoxication.

However, since 2006 there have been a number of reforms as the result of some of the Law Commission’s reports. In 2006 Parliament passed the Fraud Act partially implementing the proposals on fraud. The Corporate Manslaughter and Corporate Homicide Act 2007 implemented proposals made in Legislating the Criminal Code: Involuntary Manslaughter (1996) Law Com No 237. The Serious Crime Act 2007 implemented the Law Commission’s report Inchoate Liability for Assisting and Encouraging Crime (2006) Law Com No 300. The Bribery Act 2010 implemented the report Reforming Bribery (2008) Law Com No 313.

It is worth noting that most European countries have a criminal code. France’s code pénal was one of the earliest, being introduced by Napoleon in 1810, though there is now a new code, passed in 1992.

1.2.4 Reform of the law

Even if the law were codified, it would still be necessary to add to it from time to time. Modern technology can lead to the need for the creation of new offences. A recent example of this is that it is now a criminal offence to use a handheld mobile phone when driving. Pressure for new laws comes from a variety of sources. The main ones are:

government policy

government policy

EU law

EU law

Law Commission reports

Law Commission reports

reports by other commissions or committees

reports by other commissions or committees

pressure groups

pressure groups

It is also necessary since the passing of the Human Rights Act 1998 to ensure that new laws are compatible with the European Convention on Human Rights.

1.3 Defining a crime

As seen in section 1.1.2, it is difficult to know what standard to use when judging whether an act or omission is criminal. The only way in which it is possible to define a crime is that it is conduct forbidden by the state and to which a punishment has been attached because the conduct is regarded by the state as being criminal. This is the only definition which covers all crimes.

As the criminal law is set down by the state, a breach of it can lead to a penalty, such as imprisonment or a fine, being imposed on the defendant in the name of the state. Therefore, bringing a prosecution for a criminal offence is usually seen as part of the role of the state. Indeed, the majority of criminal prosecutions are conducted by the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS), which is the main state agency for criminal prosecutions. There are other state agencies which bring prosecutions for certain types of offences. For example, the Serious Fraud Office brings cases relating to large scale frauds, and the Environmental Agency handles breaches of law affecting the environment.

It is also possible for a private individual or business to start a prosecution. For example the RSPCA brings prosecutions on offences relating to animal welfare. However, it is unusual for an individual to bring a prosecution. Even where an individual brings a prosecution, the state still can control the case by the CPS taking over the prosecution and then making the decision on whether to continue with the prosecution or not. Alternatively the Attorney-General can stay (ie halt) the proceedings at any time by entering what is called a nolle prosequi without the consent of the prosecutor.

1.3.1 Conduct criminalised by the judges

Some conduct is criminalised not by the state but by the courts. This occurs where the courts create new criminal offences through case law. In modern times this only happens on rare occasions, because nearly all law is made by Parliament. An example of conduct criminalised by the courts is the offence of conspiracy to corrupt public morals. This offence has never been enacted by Parliament. Its creation was recognised in Shaw v DPP (1962) AC 220. In this case the defendant had published a Ladies Directory, which advertised the names and addresses of prostitutes with their photographs and details of the ‘services’ they were prepared to offer. In the House of Lords, Viscount Simonds asserted that the offence of conspiracy to corrupt public morals was an offence known to the common law. He also claimed:

JUDGMENT

‘[T]here is in [the] court a residual power, where no statute has yet intervened to supersede the common law, to superintend those offences which are prejudicial to the public welfare. Such occasions will be rare, for Parliament has not been slow to legislate when attention has been sufficiently aroused. But gaps remain and will always remain since no one can foresee every way in which the wickedness of man may disrupt the order of society.’

Another offence which has been recognised in modern times by the judges is marital rape. This was declared a crime in R v R (1991) 4 All ER 481 (see next section for details on this case).

1.3.2 Retroactive effect of case law

It is argued that it is wrong for the courts to make law. It is Parliament’s role to make the law, and the courts’ role is to apply the law. One of the arguments for this view is that Parliament is elected while courts are not, so that lawmaking by courts is undemocratic.

The other argument involves the fact that judge-made law is retrospective in effect. This means that when courts decide a case, they are applying the law to a situation which occurred before they ruled on the law. At the time of the trial or appeal they decide, as a new point of law, that the conduct of the defendant is criminal. That decision thus criminalises conduct which was not thought to be criminal when it was committed months earlier.

This point was considered in R v R, where a man was charged with raping his wife. The court in R v R had to decide whether, by being married, a woman automatically consented to sex with her husband. There had never been any statute law declaring that it was a crime for a man to have sexual intercourse with his wife without her consent. Old case law dating back as far as 1736 had taken the view that ‘by their mutual matrimonial consent the wife hath given up herself in this to her husband, which she cannot retract’. In other words, once married, a woman was always assumed to consent and she could not go back on this. This view of the law had been confirmed as the law in Miller (1954) 2 QB 282, even though in that case the wife had already started divorce proceedings. In R v R the House of Lords ruled that it was a crime of rape when a man had sexual intercourse with his wife without her consent, pointing out that:

JUDGMENT

‘The status of women and the status of a married woman in our law have changed quite dramatically. A husband and wife are now for all practical purposes equal partners in marriage.’

Following the House of Lords’ decision, the case was taken to the European Court of Human Rights in CR v United Kingdom (Case no 48/1994/495/577 (1996) FLR 434) claiming that there was a breach of art 7 of the European Convention on Human Rights. The article states:

ARTICLE

‘No one shall be held guilty of any criminal offence on account of any act or omission which did not constitute a criminal offence under national or international law at the time when it was committed.’

The European Court of Human Rights held that there had not been any breach, as the debasing character of rape was so obvious that to convict in these circumstances was not a variance with the object and purpose of art 7. In fact, abandoning the idea that a husband could not be prosecuted for the rape of his wife conformed with one of the fundamental objectives of the Convention, that of respect for human dignity. (See section 1.9 for further discussion on human rights and criminal law.)

1.4 Classification of offences

There are many ways of classifying offences depending on the purpose of the classification. They are:

by source

by source

by police powers

by police powers

by type of offence

by type of offence

by place of trial

by place of trial

1.4.1 Classifying law by its source

As already explained in section 1.2, law comes from different sources. This distinction is important from an academic point of view. So law can be categorised as:

common law (judge-made)

common law (judge-made)

statutory (defined in an Act of Parliament)

statutory (defined in an Act of Parliament)

regulatory (set out in delegated legislation)

regulatory (set out in delegated legislation)

1.4.2 Categories for purposes of police powers of detention

Police powers to detain a suspect who has been arrested depend on the category of offence. There are three categories:

summary offences

summary offences

indictable offences

indictable offences

terrorism offences

terrorism offences