Government Policies and the Shipbuilding Industry

Chapter 19

Government Policies and the Shipbuilding Industry

Joon Soo Jon*

1. Introduction

The health of the global economy is the most important factor governing the international shipbuilding industry but national economic policies play a crucial role in determining the extent to which a country’s shipbuilding industries develop and thrive or, alternatively, decline and possibly disappear. Together, national and international factors can be referred to as the macro economic environment. If the economic climate is unfavourable then industrial organisations, including shipbuilders, will face painful problems and may even have to close their production facilities.

While the macro economic environment sets the conditions that will either allow a shipbuilding industry to thrive, or not, the choices made, decisions taken, by each individual shipbuilding business are crucial to its survival and prosperity. Good decisions at the enterprise level can partially offset an unfavourable macro structural environment.

Government policies in promoting shipbuilding industry are largely implemented through various types of financial assistance such as direct financial aid and or by guaranteeing loans.

Therefore, the main objective of this chapter is to review the historic development of successful shipbuilding countries and provide informative cases for reference in the face of changing national and global circumstances. The structure of this chapter is as follows. The next section focuses on the impact of Government intervention on the shipbuilding industry. Section 3 considers the global shift in the shipbuilding industry and structural changes in this market. Section 4 examines the role of government in developing or supporting the shipbuilding industry. Section 5 explores the impact of recent changes in economic environment on the leading shipbuilding countries such as Japan, South Korea and China. The final section presents the summary and conclusions.

2. The Impact of Government Intervention on the Shipbuilding Industry

2.1 Shipbuilding enterprise

Shipbuilding enterprises can be categorised as falling into two distinct groups: those that engage purely in shipbuilding and those that are diversified enterprises where shipbuilding is only one of a portfolio of interests that may have very little in common. In addition there is also an important distinction to be made between shipbuilders that are private firms and those that are state corporations.

There are strengths and drawbacks associated with being either an independent shipbuilding enterprise or the shipbuilding arm of a conglomerate. Not surprisingly both structures are frequently found within a national shipbuilding industry. Shipbuilders belonging to diversified corporations have the advantage of being able to rely on corporate resources for expansion and support which are independent of the state of the shipbuilding market. Consequently, in periods of shipping recession, the shipbuilding member of the group can call upon reserves acquired in other market areas to overcome short-term cash flow difficulties. Moreover, this shipbuilder may be able to use group resources to modernise its production facilities at a time when independent shipbuilding firms are being obliged to cut back their overheads and capacity. This enables the shipbuilding member of the group to boost its competitive position compared to other shipbuilders. The flexibility inherent in the within-group transfer of resources to the benefit of shipbuilding operations has been important to the success of Japanese and South Korean shipbuilders.

Access to well organised and funded marketing, and research and development, can be another advantage of being part of a conglomerate. But there is one more, less easily quantifiable, but very important, advantage to being in a big group. Conglomerates have political clout. These diversified, large companies command respect and influence in industrial, financial and political circles. This can mean easier access to capital markets and more sympathetic treatment by politicians, than could be expected by a dedicated shipbuilding company. These factors add up to substantial competitive advantage for conglomerate members.

There is, though, a downside to being part of a conglomerate. Although a shipbuilding subsidiary should theoretically benefit from the resources its parent group devotes to R&D and marketing, the bureaucracy surrounding those functions in a large conglomerate may in practice offset any gains.

Unfortunately, a hierarchical, overly-bureaucratic form of organisation can easily lead to inflexible decision making and rivalry between the managements of member organisations. This can lead to individuals vying for power within the hierarchy of corporate head-office rather than working for the good of the shipbuilding enterprise.

Enterprises solely focused on shipbuilding can, on the other hand, be much more flexible and resilient. As Todd notes:

“They [dedicated shipbuilders] tend to be more loosely organized and more flexible and responsive to changing circumstances in consequence. The independent shipbuilding firm may continue in shipbuilding operations because it simply has no choice – other than closure – whereas the shipbuilding subsidiary may find itself steadily undermined because its corporate parent feels that greater profits can be made by switching assets out of shipbuilding into a more lucrative field. No matter how dedicated the shipbuilding managements of the subsidiary, their subservience to the greater corporate interest takes precedence over their sectoral interests and conceivably, group shipbuilding operations may be phased out not because they are lacking in viability but owing to their low profitability relative to other group interests. It is fair to say that unless the independent shipbuilder can grow to such a position that resources become little or no object, the chances of survival cannot be assured.”1

2.2. Impact of government intervention

The state is not necessarily, or even usually, a disinterested observer of the shipbuilding scene. Governments often intervene in their shipbuilding industries. Intervention can range from macro economic management to direct intervention at enterprise level.

This chapter looks at two ways governments can intervene to shape the development of a national shipbuilding industry. One way open to the state is to order the building of warships. Through its allocation of naval contracts, the state often appears to be supporting shipbuilding as a kind of implicit regional policy. Awarding warship orders to particular yards can be a way of protecting employment. The balance between ordering motivated by such social factors and objective assessment of national defence needs, seems to vary over time.

The other way is formulating policies to promote the shipbuilding industry in direct and indirect ways. Government’s role in developing the shipbuilding industry has mainly focused on the financial assistance in various forms.

Governments act as credit guarantors for the construction of ships at their domestic shipyards and often cooperate with shipyards in devising new forms of financial inducement to shipowners to place orders. These can take the form of disguised subsidies to directors. Also a government-sponsored shipbuilding programme with favourable financing (in terms of interest rate and repayment period) provides a great impetus to the development of the domestic shipbuilding industry.

3. The Global Shift of the Shipbuilding Industry

3.1 Structural change in world shipbuilding

In the early 1990s South Korean shipbuilders embarked on an ambitious expansion strategy, despite warnings from the rest of the global shipbuilding industry that the move threatened price stability by creating a large excess of capacity compared to supply. The expansion of the South Korean capacity included new building docks at Hyundai Heavy Industry, modifications at Samsung allowing the building of VLCCs and similarly sized vessels and the construction of the large, modern VLCC capable Halla yard at Mokpo.

Japanese shipbuilders responded by booking large numbers of orders at comparatively lower prices. The price competitiveness of the Japanese shipbuilding industry then deteriorated due to a sharp rise in the yen which rose at one time to as high a level as ¥95 per US dollar. This strengthening of the yen led Japanese yards to buy foreign materials and equipment where possible. Meanwhile the world orderbook increased, mainly due to demand for large-size bulkers and containerships.

Trends of world economy, good or bad, generally begin to produce their effect on shipping with a time lag of around one year, and on shipbuilding one year later than shipping.

3.1.1. Japan

The profitability of the Japanese shipbuilding industry is greatly dependent on exchange rate with the US dollar. Because ship prices are usually denominated in US dollars the sharp appreciation of the yen meant that prices realised by the Japanese yards effectively fell dramatically.

In 1994, the yen rose further to a daunting level of ¥95 per US dollar. Although it then returned to ¥100, these successive surges in the yen caused the shipbuilding industry to become less and less price competitive. However, since the late 1990s the weakening Japanese Yen has once again strengthened the price-competitiveness of Japanese shipbuilders.

3.1.2 South Korea

The OECD shipbuilding working party group considered South Korea’s capacity expansion for the first time at a meeting held in January 1995. A representative of the South Korean government said that the government had no legal basis to impose any restraint on expansion by private firms because a matter of this sort was entirely left to the independent judgment of each private enterprise. While the expansion was happening the gap that had existed between Japan and South Korea in the areas of non-price competitiveness, such as technological skills and quality where Japan claimed to lead, was closing.

South Korea succeeded in achieving a level of quality comparable to that of Japan, at least as far as the hull structure is concerned. This was achieved as result of the large amount of experience gained throughout the 1980s, building diverse types of ships and marine structures. But South Korea still lags behind Japan in such areas as marine engines and ship-related equipment.

3.1.3 Western Europe

Germany has finally stabilised its economy following the economically difficult, reunification. The country’s shipbuilding industry, which had been not been particularly dynamic in the 1980s gradually revived throughout the 1990s with an expanding order book.

Orders were at a healthy level during most of the decade, with the national industry especially strong in the container ship and passenger vessel sectors. By the beginning of the 2000s, however, Germany was facing major problems. In 2001 deliveries amounted to 55 ships, totalling just over 1m gt. But very few orders were taken during that year with government-related contracts playing an important part in the survival of many yards. A number of yards also started to look more at conversions and refurbishments to compensate for a lack of newbuilding orders.

Germany had become vulnerable because of its specialistion. Korean shipbuilders were increasingly able to beat German owners on price for container ship orders while the sharp downturn in the cruise industry, exacerbated by the 11 September terror attacks, hit passenger ship builders like Meyer Werft very hard.

Denmark is another important EU shipbuilding country. Odense Shipyard is by far the country’s largest, and is particularly well known for its high productivity attained through sophisticated computerisation and robotics. A large portion of its order book comes from A P Moller, one of the biggest ship owners in Europe.

3.1.4 Other countries

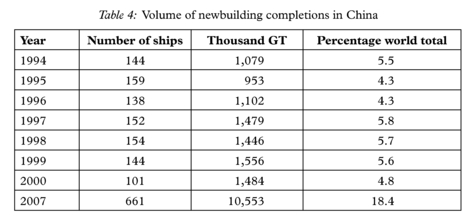

China has ranked as the third largest shipbuilding country, after Japan and South Korea, since 1992. In 1995, China constructed the New Dalian dockyard, with one building capable of building 250,000 dwt ships.

Poland built VLCCs back in the 1970s but not in recent years. Since the demise of communism, its yards have been successful in attracting newbuilding orders from Greece and Western Europe. Although existing shipbuilding facilities are old, domestic supplies of marine equipment, including main and auxiliary engines makes the Polish shipbuilding industry largely self-sufficient. This insulates them from currency fluctuations and allows them to book orders at lower prices. An upward trend in the volume of ship construction has become apparent since 1992 as a means to earn foreign currency reserves through ship exports.

Brazil is another country with shipbuilding potential. However its shipbuilding programme has suffered from economic turmoil and a shortage of funds. Although Brazil has technological skills comparable with the international standards for building large-size vessels, including DH (double hull) tankers, the real problem lies in its price competitiveness. In an attempt to rectify this Brazil is promoting the rationalisation of its yards. In 1995 the merger of ISIBRAS(Ishikawajima do Brasil) Yard and Verolme was the largest ever in Brazil.

Structural changes are emerging on a global scale in the shipbuilding industry over the second half of the 1990s and 2000s, while at the same time being affected by structural changes in the shipping industry.

3.2 Demand and ship cycles

Ship costs are strongly affected by the costs of procuring materials and labour in the shipyards. Moreover, shipyard expenses and production costs in general are very sensitive to technological change – a supply factor. Technological change, however, has implications, which extend from supply to demand factors.

Great store was put on the effects of innovation on the competitiveness of industrial organizations.2 According to this theory, shipbuilders fall into the technological leader category and attract a growing market share as a result of their progressive practices. Those categorised as technological laggards, though, are compelled to react to innovation to retain a share of the market.

Obviously, technological change is having a dramatic impact on demand from both perspectives: the lead firms taking away demand from the laggards and they, in turn, being forced to find compensatory demand largely with government help.

It is important to stress, however, that the level of aggregate merchant ship demand is set independently from the actions of either shipbuilders as a whole, or governments intervening to protect national shipbuilding industries. Aggregate demand is, in fact, the outcome of conditions affecting world trade.

The actions of individual shipbuilding enterprises and individual governments may partially regulate the demand for a small component of world shipbuilding, but they will not greatly affect overall demand conditions. In other words, aggregate demand for shipping is very largely an exogenous factor; something outside of the control of the industry or government institutions.

The approach adopted here is one which sets shipping as the derived demand outcome of world trade conditions. It assumes that, derived broadly, it conforms to two categories: a “traditional” ship cycle manifested through the effects of trade on the production of “typical” ships; and a “modern” ship cycle in which trade effects are expressed in varying ways depending on the type of specialised ship.

Warship production, of course, is influenced by different factors. These vessels not only have their own supply requirements which can be quite different from those pertaining to merchant ships, but they also respond to a peculiar form of derived demand that is very different from the ship cycles affecting merchant ships.

Governments intervene in the market for two main reasons order; to bolster the demand for ships and thereby provide support for an otherwise ailing domestic shipbuilding industry. Governments can also intervene in regional economies, which are suffering from depressed conditions in order to bolster regional development and ameliorate the consequences of locally concentrated unemployment. Ideally, the two objectives complement each other. Ailing shipbuilders receive a boost from government aid, and depressed communities receive a form of employment stabilisation through government support for the job-creation organisations.

Governments are most able to affect demand by ordering warships. Policies using warship procurement as a means of intervention have different effects on shipbuilding than those aimed at stimulating merchant ship demand. This is because demand for commercial vessels is linked to the international trade cycle and is dependent upon the actions of a multitude of mainly private shipping firms. When it comes to warship building, however, national governments are able to control demand, subject to limits on the overall defence budget. Wherever possible, governments support their national shipbuilding industries by placing orders with local yards.

Warship producers are however highly vulnerable to government whims. Overall economic factors also impact on warship building by putting pressure on the national and defence budgets. In practice warship production is, in its own way, as cyclically unstable as commercial shipbuilding. Warship producers can attempt to secure export orders, but in general they are highly dependent on a single, very powerful customer – their government.

4 The Role of Government and Its Policies to Promote the Shipbuilding Industry

4.1 State subsidies, naval shipbuilding

4.1.1 State subsidies

Shipbuilding subsidies have long been, and remain highly controversial. Ship prices are frequently distorted by the effects of state subsidy. One commentary points to the incompatibility of the “heavy over-tonnaging of virtually all types of ships” on the one hand, and the continual scramble to garner newbuilding orders on the other. The motivation for the imbalance between supply and demand is simple and stems from the belief held by all states that their shipbuilders are too important to be allowed to fail. Consequently, “there is great temptation to support ship production beyond ‘normal’ commercial limits. Whatever form it takes, the end-result is a financial subsidy borne by the stat”.3