Effect of an Adjudicator’s Decision

EFFECT OF AN ADJUDICATOR’S DECISION

(1) Overview

6.01 Once an adjudicator’s decision has been delivered, the successful party will generally be expecting the unsuccessful party to comply with that decision, for example by payment of monies or compliance with a declaration. Whether the unsuccessful party complies with the adjudicator’s decision, or whether the decision is summarily enforced by the courts, the decision of the adjudicator has many important effects. This chapter explores those general effects; identifies how an adjudicator’s decision can become permanently binding on the parties; explores the circumstances in which there can be a set-off against a payment due pursuant to a decision; and discusses the prohibition on the readjudication of a dispute which is substantially the same as a dispute which has previously been determined.

(2) General Effects of an Adjudicator’s Decision

6.02 An adjudicator’s decision:

1. Is private between the parties and cannot be used as a precedent in any dispute between other parties unless there are express contract terms to the contrary.

2. Is temporarily binding, and this will extend to include matters which may properly be inferred from the decision.

3. Must be complied with by the parties until the dispute is finally determined (which may be by litigation, arbitration, or agreement), subject to any successful challenge to enforceability.

4. Does not alter a contractual right or liability but temporarily determines rights and liabilities until final determination.

5. Creates a new contractual cause of action for non-compliance.

6. Will ordinarily give rise to a separate contractual entitlement to immediate payment without set-off.

7. Prohibits any re-adjudication of a dispute which is substantially the same as the dispute determined.

Private between the Parties

6.03 Adjudication is a dispute resolution procedure that arises as a result of a contractual relationship and the outcome cannot therefore affect anyone who is not a party to the adjudication, either directly or by use as a precedent in other proceedings.1 However, the temporarily binding nature of an adjudicator’s decision does mean that it acts as a precedent in any subsequent disputes between the same parties. Unlike decisions of the courts, which are available for public review, decisions by adjudicators in the United Kingdom are not published.2 Some adjudication agreements or construction contracts specifically make the adjudication proceedings and outcome confidential. In the absence of express contractual terms, any information or document provided in connection with the adjudication (including the decision itself) is not confidential unless the party supplying it has indicated it is to be treated as confidential.3

6.04 Adjudicators’ decisions are therefore more akin to arbitral awards than court judgments, as arbitral awards are generally not available to the public.4 However, adjudication decisions are not wholly analogous to decisions made under the Arbitration Act 1996. For example, there is no statutory equivalent in the Housing Grants Construction and Regeneration Act 1996 (‘the 1996 Act’), or in its 2009 amendments, of s. 66 of the Arbitration Act 1996, which provides that an arbitral award may, with the leave of the court, be enforced in the same way as a judgment or order of the court. There is no procedure for the entry of an adjudicator’s decision as a judgment.5 Instead, the right to enforce an adjudicator’s decision is purely contractual:

37. The decision of an adjudicator is not like an award of an arbitrator or the judgment of a court and directly enforceable. It is enforceable at all simply because by their contract the parties have agreed to comply with it or to give effect to it. This is so whether the parties have expressly agreed in their contract to a procedure for adjudication, as in the present case, or whether the relevant provisions of The Scheme for Construction Contracts have been implied into their contract by virtue of the provisions of Housing Grants, Construction and Regeneration Act 1996 s. 114(4).6

Temporarily Binding until Final Determination

6.05 Section 108(3) of the Act requires a construction contract to provide that the decision of the adjudicator is binding until the dispute is finally determined by legal proceedings, arbitration, or agreement of the parties. The Court of Appeal described the effect of this provision in the following way:

26. … The adjudicator’s decision, although not finally determinative, may give rise to an immediate payment obligation. That obligation can be enforced by the courts. But the adjudicator’s determination is capable of being reopened in subsequent proceedings. It may be looked upon as a method of providing a summary procedure for the enforcement of payment provisionally due under a construction contract.7

6.06 If the adjudication regime in a construction contract does not contain clauses to satisfy the mandatory requirements of the Act, the rules of the Scheme apply.8 Paragraph 23(2) of the Scheme encompasses the requirements of s.108(3) of the Act, requiring the parties to comply with a decision of an adjudicator until the dispute is finally determined.

6.07 The adjudicator’s decision gives rise to a separate contractual obligation to comply with the decision.9 Proceedings to enforce an adjudicator’s decision are proceedings to enforce that contractual obligation.10 Failure to comply with a valid adjudicator’s decision is a new breach of contract and a cause of action arises at the date when the relevant party should have complied with the adjudicator’s decision.11

Time for Compliance

6.08 As an adjudicator’s decision is temporarily binding, the parties must comply with it, whether it relates to an order for payment or a declaratory decision by the adjudicator.12 If conducted under the Scheme, in the absence of directions from the adjudicator as to time for performance, the decision is to be complied with immediately upon delivery.13 This means that the parties should comply with the decision without debate or question. If a peremptory order is made under paragraph 23(1) of the Scheme that does not affect the time for compliance.14

6.09 However, if the losing party intends to challenge the enforceability of the decision, then there is no requirement that it should comply with the decision before being able to advance its case that the decision is unenforceable:

19. … Naturally the Act assumes that such a final determination is likely to follow the decision. That is consistent with the concept of adjudication whereby a dispute would be resolved during the course of a contract and only resurrected for final determination, if required, at a later stage. ‘Pay now; argue later’, as some are wont to say. In my judgment there is nothing in the Act (or the Scheme, if applicable) which requires a party who wishes to challenge a decision of an adjudicator to comply with it before being able to advance its case, any more than a party is precluded from subsequently challenging a decision, having complied with it .…15

6.10 On the contrary, a party intending to resist enforcement on the basis that the adjudicator’s decision is a nullity should not make any payment in respect of the decision, as to do so may result in the paying party being considered to have made an election that the decision is valid.16

Final Determination

6.11 Subject to any time bars (whether contractual or statutory), or an agreement to accept an adjudicator’s decision as final, a party may commence legal proceedings or, if the contract contains an arbitration clause, an arbitration, for final determination of the dispute. In the meantime, unless the losing party has reason to resist enforcement of the adjudicator’s decision,17 it must comply with it, including making payment of any amounts awarded by the adjudicator.

6.12 Disputes referred to adjudication commonly involve the consideration of substantial factual material and any proceedings for final determination will be equally fact-heavy. A losing party seeking finality will therefore typically have to start a court claim (or arbitration if there is an arbitration agreement).18 However, if there is no arbitration agreement and there is a point decided by the adjudicator that can be finally determined as a matter of law without a factual enquiry (for example, a point of contractual construction) then it may be possible, by the issuing of a Part 8 claim, to have that point finally determined, potentially at the same time as any summary judgment proceedings for enforcement.19

6.13 Where a party issues proceedings for an adjudicator’s decision to be overturned, then the cause of action is heard anew and the adjudicator’s decision has no bearing on the case unless the parties agree otherwise, nor does it reverse the burden of proof in any subsequent litigation. In other words, it is not incumbent on the losing party to show that the adjudicator’s decision was not justified: City Inn Ltd v Shepherd Construction Ltd (2001) (Key Case).20

6.14 An adjudicator’s decision does not create or modify a right or liability under the contract in question but is equivalent to a determination or upholding of rights or liabilities under the contract.21 An adjudicator’s decision is an expression as to liability (and usually quantum); it does not alter or replace the original cause of action that was the subject of the dispute, since the underlying cause of action survives and neither merges into, nor is superseded by, the disputed adjudicator’s decision.22 Therefore, if the adjudicator’s decision is found to be a nullity, the parties do not lose their original cause of action, subject to any express finality provisions in the contract.23

6.15 In the event that it is found on final determination that there has been an overpayment as a result of a payment made pursuant to an adjudicator’s decision, that overpayment can be recovered either by way of claim pursuant to an implied term that any overpayment is to be repaid in such circumstances or in restitution24 (NB: not followed in [2013] EWHC 1322 (TCC)).

Finality by Agreement

6.16 Section 108(3) provides that the parties may agree to accept the decision of the adjudicator as finally determining the dispute.

6.17 There is no reason why parties to construction contracts cannot agree that they will be finally bound by the decision of the adjudicator either at any time before the adjudication is commenced (for example by express drafting in the construction contract itself or the adoption of particular adjudication rules which state that the decision would have that effect) or at any time during or after the adjudication.

6.18 Like any other contractual agreement, the courts would be unlikely to interfere with the contractual freedom of parties to agree the decision of an adjudicator was to be final.25 Similarly, a court will not enforce an adjudicator’s decision through summary judgment if the dispute that was the subject of the decision has been compromised after (or indeed before) an adjudicator has delivered his decision.26 In such circumstances, the defendant will have a complete defence to the claimant’s application, and the claimant will, in all likelihood, be liable for the costs of the summary judgment application and any hearing to determine the defence of compromise.27 However, a settlement agreement will not be a defence to enforcement proceedings where a party has defaulted on that settlement agreement.28

Contractual Finality Provisions

6.19 One example of a finality provision in the construction contract is where the parties agree that a decision shall become final unless certain steps, such as commencing arbitration or litigation, are taken within an identified period of time. However, in the absence of any such agreement, the only possible time limit to a party seeking final determination of a matter previously referred to adjudication is the relevant statutory time bar to the right to bring a claim in respect of a cause of action imposed by the Limitation Act 1980.

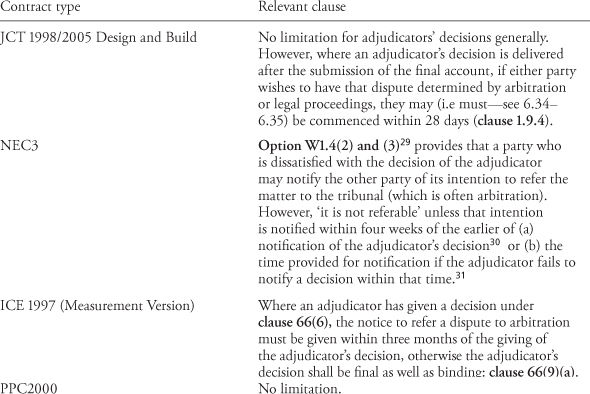

6.20 Some of the standard-form construction contracts provide a time limit for the commencement of litigation or arbitration following an adjudicator’s decision, as can be seen in Table 6.1.

Table 6.1 Standard-form Contract Time Limits

6.21 The courts’ approach to interpreting these clauses appears to favour certainty and finality. In Jerram Falkus Construction Ltd v Fenice Investments (No. 4) (2011) (Key Case),32 Coulson J upheld the interpretation of clause 1.9.4 that said any adjudication decision given after the Final Account or Final Statement must be challenged within 28 days of the decision.33 The failure to give notice within that 28 days meant the adjudication decision became final and could not be challenged. In Anglian Water Services Ltd v Laing O’Rourke Utilities Ltd (2010),34 the finality provisions in clause 93.1 of NEC2 were found to be compatible with the 1996 Act as the requirement to adjudicate disputes as a mandatory first step before seeking final determination did not fetter the right to adjudicate at any time and could be operated consistently with the other provisions of the Scheme.

6.22 However, such finality provisions may be construed as not requiring strict compliance with the letter of the provision where one of the parties to the contract has become the subject of an administration order or is in liquidation. In Straw Realisations (No. 1) Ltd (formerly known as Haymills (contractors) Ltd (in administration) v Shaftsbury House (Developments) Ltd 35 there was a provision that a decision would become final unless a notice was served within three months of the decision stating that the dispute was to be referred for final determination. A letter within three months of the decision that simply indicated that the claim for payment was considered unenforceable and rejected (but did not expressly give notice of intention to refer to legal proceedings) was held to satisfy the provision.

6.23 The calculation of the relevant period of time must be interpreted in accordance with the particular facts and contractual provision. Where an adjudicator provided an initial decision, for example on matters such as jurisdiction, before providing his decision on the substantive dispute, and the contract required notice of final determination within a period of time from the ‘determination’ of the adjudicator, that time period ran from the final decision by which he discharged his functions: Midland Expressway Ltd and ors v Carillion Construction Ltd and ors (No. 3) (2006).36 Jackson J found that the natural interpretation of ‘determination’ in the contract did not refer to ‘any earlier ruling or decision which the adjudicator may make along the way’:

87. … The adjudication process, as provided for by the 1996 Act … is intended to be a speedy and efficient procedure. It would be contrary to the purpose of this procedure and it would not make commercial sense if time starts to run … at any point in the course of the adjudication. This might lead to the need for successive actions. It might also lead to the need for litigation while the adjudication is still in progress. Furthermore, such litigation might turn out to be fruitless or unnecessary after the adjudicator has given his final decision.

Effect of the Decision in Subsequent Adjudications

6.24 An adjudicator appointed in a subsequent adjudication has no jurisdiction to set aside, revise, or vary his previous decision(s) or those of any other adjudicator. Accordingly, findings of fact or law on issues in previous adjudication decisions will be binding on the parties and a subsequent adjudicator alike, as long as that issue was part of the dispute referred in the previous adjudication so that the adjudicator was given jurisdiction to decide the issue37 and the decision is not otherwise unenforceable, or the parties agree otherwise.

6.25 It is possible for parties to agree to be bound by a constituent part of a decision or any process of reasoning adopted in the course of reaching a conclusion on the overall dispute.38 However, where the reasoning within that decision is not an essential component of, or basis for that decision, it will not be binding.39

6.26 An adjudicator may consider facts and matters considered in previous adjudications in reaching a conclusion, without trespassing on the previous decision.40 However, if he reaches a different conclusion based on these same facts and the same cause of action, then that decision will be unenforceable.41

Compliance with Matters Properly Inferred

6.27 The parties may also temporarily be bound by consequences that follow naturally from an adjudicator’s decision. The most common consequences to flow from adjudicators’ decisions concern extensions of time and their effect on the employer’s entitlement to levy liquidated and ascertained damages, or the contractor’s entitlement to claim prolongation costs and/or other loss and expense.42 Thus, where an adjudicator has decided a ten-week extension of time was due, the parties would have to abide by that decision. This would mean that the employer could not deduct liquidated damages for that period; however, there could still be an argument between the parties as to what, if any, compensation was payable to the contractor.43 Each case will turn on its facts and precisely what the adjudicator decided.44 See also the discussion about setting off liquidated damages against an adjudicator’s decision at 6.43 below (and following).

6.28 An obligation to comply with matters which ‘follow logically’ from an adjudicator’s decision was enforced where an adjudicator’s decision contained ‘inexorable logic’ which meant that the claimant had been overpaid by the defendant even though no sums were actually awarded;45 and where the adjudicator made a declaration as to the net value of the final account without giving a direction to pay the amounts due.46

6.29 However, in another case the court declined to find that payment of liquidated damages flowed naturally from an adjudicator’s decision that certificates of non-completion were to be issued. The adjudicator had declined to make any financial award or determination of the financial consequences in respect of liquidated damages in the absence of such certificates.47 Similarly, whilst the natural corollary of an adjudicator’s decision may be to increase the number of expended hours in a ‘pain/gain’ calculation, where there is disputed evidence as to how that ‘pain’ is calculated, a deduction for that sum will not necessarily follow logically from the adjudicator’s decision.48