Staying Enforcement

STAYING ENFORCEMENT

(1) Introduction

8.01 The substantive grounds on which the enforcement of an adjudicator’s decision may be resisted are discussed in Chapters 9, 10, and 11. However, in circumstances where such grounds do not exist and the decision is therefore enforecable, a party may still be able to avoid the obligation to make a payment in respect of the decision by seeking either a stay of execution of the order enforcing the award, or by seeking a stay of the enforcement proceedings themselves. These approaches, whilst having the same practical effect, are procedurally distinct and are dealt with separately in each section in this chapter.

8.02 RSC Order 471 grants the court a wide discretion to stay the execution of a judgment or order where there are ‘special circumstances’ rendering it ‘inexpedient’ to enforce a judgment:

(1) Where a judgment is given or an order made for the payment by any person of money and the court is satisfied on an application made at the time of the judgment, or order, or at any time thereafter by the judgment debtor or other party liable to execution –

(a) that there are special circumstances which render it inexpedient to enforce the judgment or order…

… the court may by order stay the execution of the judgment or order… either absolutely or for such period and subject to such conditions as the court thinks fit.

8.03 Where there is an enforceable adjudicator’s decision the court will order summary judgment. However, a stay of execution of that order prevents the successful party from doing anything with that order until some further order is made lifting the stay (or any conditions attached to the stay cease to apply). The most frequent basis for applying for a stay of execution is the impecuniosity of the successful party.2 Even though they are entitled to summary judgment in the amount sought, where there is a sufficiently real risk that they may be unable to repay the sum awarded in the event that the temporarily binding adjudicator’s decision is later overturned in court or arbitral proceedings, then it is considered inexpedient to require payment to be made.

8.04 As to staying the enforcement proceedings themselves, if parties have agreed a particular method by which disputes are to be resolved, then a court has an inherent jurisdiction to stay court proceedings brought in breach of that agreement,3 even where that agreement is a general agreement to refer disputes to alternative dispute resolution.4 However, in most adjudication enforcement cases, the courts have refused to stay, or even adjourn, summary enforcement proceedings pending other proceedings. The extent to which this principle may apply to court proceedings to enforce an adjudicator’s award and whether such proceedings should be stayed for the enforcement to be decided by alternative means is discussed in the final section of this chapter.

(2) Stay of Execution of Enforcement Order on Grounds of Impecuniosity

8.05 Stays may be granted where the unsuccessful party convinces the court that the successful party’s impecuniosity is such that payment should not be made. The key principles in such a consideration are as follows:

1. The degree of impecuniosity is all important. If the successful party is in liquidation or does not dispute its insolvency, a stay will usually be granted. If there is no proper evidence of financial vulnerability, a stay will be denied. There are many shades of impecuniosity between these two extremes.

2. A stay on grounds of impecuniosity may not be granted where:

(a) the successful party is not in a significantly worse financial position than at the time the contract was entered into; or

(b) the successful party’s financial condition was due to the failure to be paid the money awarded in the adjudicator’s decision.

3. The onus is on the unsuccessful party seeking the stay to adduce evidence of a very real risk of future non-payment.

4. There may be cost ramifications if a party wrongly challenges the enforceability of a decision and seeks a stay in circumstances where no such position is tenable.

Insolvency Rules

8.06 Rule 4.90 of the Insolvency Rules provides:

(1) This rule applies where, before the company goes into liquidation there have been mutual credits, mutual debts or other mutual dealings between the company and any creditor of the company proving or claiming to prove for a debt in the liquidation.

(2) An account shall be taken of what is due from each party to the other in respect of the mutual dealings and the sums due from one party shall be set off against the sums due from the other.

…

(4) Only the balance (if any) of the account is provable in the liquidation. Alternatively (as the case may be) the amount shall be paid to the liquidator as part of assets.

8.07 The obligation to implement an adjudicator’s decision without delay does not prevail over a party’s entitlements upon the insolvency of another party, such as mutual setting off of accounts under 4.90 of the Insolvency Rules.5

8.08 Accordingly, whilst the general principle is that adjudicators’ decisions are to be enforced without cross-claim or set-off, where the judgment creditor (or the successful party from the adjudication) is insolvent, that rule is displaced. If this were not so there would be a real risk that payment in respect of an adjudicatior’s decision, which is intended only to be temporarily binding, would lead to unfairness. In particular, if the adjudicator’s decision were to be reversed in a subsequent final determination of the dispute in litigation or arbitration, it would be very unlikely that the money paid over pursuant to the adjudicator’s decision could be recovered from the insolvent party. This may amount to ‘special circumstances’ under Order 47(1)(a) justifying a stay of enforcement of the decision. If no stay was granted, the judgment debtor (or unsuccessful party from the adjudication) would be denied its rights to a full reckoning under the Insolvency Rules and would run the real risk of receiving only a limited dividend, usually as an unsecured creditor—all as a consequence of a temporarily binding decision. Therefore, where there is sufficient evidence to establish impecuniosity, summary judgment enforcing the adjudicator’s decision is likely to be entered but a stay of execution of that judgment will be ordered.

8.09 The Court of Appeal explained the reasoning for this approach in its decision in Bouygues (UK) Ltd v Dahl-Jensen (UK) Ltd (2000)6 in which Dahl-Jensen was in liquidation:

33. … If Bouygues is obliged to pay to Dahl-Jensen the amount awarded by the adjudicator, those monies, when received by the liquidator of Dahl-Jensen, will form part of the fund applicable for distribution amongst Dahl-Jensen’s creditors. If Bouygues itself has a claim under the construction contract, as it currently asserts, and is required to prove for that claim in the liquidation of Dahl-Jensen, it will receive only a dividend pro rata to the amount of its claim. It will be deprived of the benefit of treating Dahl-Jensen’s claim under the adjudicator’s determination as security for its own cross-claim. …

35. … In circumstances such as the present where there are latent claims and cross-claims between parties, one of which is in liquidation, it seems to me that there is a compelling reason to refuse summary judgment on a claim arising out of an adjudication which is necessarily provisional. All claims and cross-claims should be resolved in the liquidation in which full account can be taken and a balance struck. That is what r.490 of the Insolvency Rules 1986 requires.

36. It seems to me that those matters ought to have been considered on the application for summary judgment. But the point was not taken before the judge and his attention was not, it seems, drawn to the provisions of the Insolvency Rules 1986. Nor was the point taken in the notice of appeal. Nor was it embraced by counsel for the appellant with any enthusiasm when it was drawn to his attention by this Court. In those circumstances—and in the circumstances that the effect of the summary judgment is substantially negated by the stay of execution which this court will impose—I do not think it right to set aside an order made by the judge in the exercise of his discretion. I too would dismiss this appeal.

Principles of Stay of Execution

8.10 In Wimbledon Construction Company 2000 Ltd v Vago (2005) (Key Case),7 Judge Coulson set out the following principles as relevant to an application for staying enforcement on the grounds of impecuniosity:

26. … (a) Adjudication … is designed to be a quick and inexpensive method of arriving at a temporary result in a construction dispute.

(b) In consequence, adjudicators’ decisions are intended to be enforced summarily and the claimant (being the successful party in the adjudication) should not generally be kept out of his money.

(c) In an application to stay the execution of summary judgment arising out of an Adjudicator’s decision the court must exercise its discretion under Order 47 with considerations (a) and (b) firmly in mind (see AWG).

(d) The probable inability of the claimant to repay the judgment sum (awarded by the Adjudicator and enforced by way of summary judgment) at the end of the substantive trial, or arbitration hearing, may constitute special circumstances within the meaning of Order 47 rule 1(1)(a) rendering it appropriate to grant a stay (see Herschel).

(e) If the claimant is in insolvent liquidation, or there is no dispute on the evidence that the claimant is insolvent, then a stay of execution will usually be granted (see Bouygues and Rainford House).

(f) If the evidence of the claimant’s present financial position suggested that it is probable that it would be unable to pay the judgment sum when it fell due, that would not usually justify the grant of a stay if:

(i) the claimant’s financial position is the same or similar to its financial position at the time the relevant contract was made (see Herschel); or

(ii) the claimant’s financial position is due, either wholly or in significant part, to the defendant’s failure to pay those sums which were awarded by the Adjudicator (see Absolute Rentals).

8.11 These principles have been endorsed in many cases and help to ensure that stays are granted in circumstances ‘consistent with the overriding objective, [where] the justice of the case demands it’.8 The application of these principles will depend on the facts of each case. There will be some cases in which it would be ‘wholly unjust and inequitable if the judgment sum was not the subject of a stay of execution’.9 There are some instances where justice is better served when the stay is made over only part of the judgment sum,10 or where it is made conditional upon monies being paid into court rather than allowing the defendant the benefit of the sums during the period of the stay.11

Types of Financial Hardship

8.12 The first question to be considered on an application for a stay of execution based on impecuniosity is whether the type and/or level of financial hardship is such that the claimant will be unable to repay any sums paid to it pursuant to the adjudication decision. As described above, where the judgment creditor is in liquidation, the Court of Appeal has confirmed there are grounds to either refuse summary judgment or to stay execution.12 However, there are many different types of financial hardship along the continuum between solvency and liquidation, and this provides scope for the court to exercise its discretion. A stay application must be supported by evidence of impecuniosity, usually in the form of up-to-date financial information relating to the company seeking enforcement.13 However, it is relevant to consider not just the latest accounts but also the current trading position and future trading prospects of the successful party.14

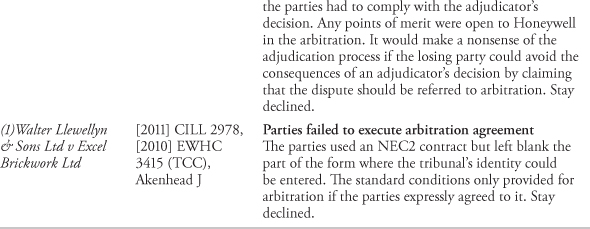

8.13 As can be seen in Table 8.1, the courts have considered many types of financial hardship, from company voluntary arrangements15 to floating charges over assets,16 credit references showing ‘maximum risk’ and county court judgments,17 or accounts and credit rating indicating a high risk of insolvency.18 Applications for stays were denied in each of these circumstances.

8.14 In fact, there have only been a handful of successful applications for stays, including where the judgment creditor:

1. Was in administrative receivership, and monies were paid into court.19

2. Had gone through incomplete winding-up procedures as at the date of the application for summary judgment (when the court stayed the enforcement pending the hearing of a winding-up petition 14 days later).20

3. Had significant debts, an unsatisfied county court judgment, and the judgment debtor had a significant adjudication decision which it could set off against the decision in question.21

4. Was in administration by order of the court22 or in accordance with Schedule B1 of the Insolvency Act 1986.23

8.15 In Straw Realisations (No. 1) Ltd v Shaftsbury House (Developments) Ltd (2010)24 Edwards-Stuart J set out the applicable principles to the different types of financial difficulties:

(1) A clause in a contract that purports to supersede the obligation to comply with an adjudicator’s decision, in this case the provision for a mutual setting off of the accounts between the parties on the happening of certain events as set out in clause 8.5 and an obligation only to pay the balance and the restriction on any further payments, cannot prevail over an obligation to comply with the decision of an adjudicator: see Ferson v Levolux and Verry v Camden.

(2) If, at the date of the hearing of the application to enforce an adjudicator’s decision, the successful party is in liquidation, then the adjudicator’s decision will not be enforced by way of summary judgment: see Bouygues v Dahl Jensen and Melville Dundas. The same result follows if a party is the subject of the appointment of administrative receivers: see Melville Dundas.

(3) For the same reasons, I consider that if a party is in administration and a notice of distribution has been given, an adjudicator’s decision will not be enforced.

(4) If a party is in administration, but no notice of distribution has been given, an adjudicator’s decision which has not become final will not be enforced by way of summary judgment. In my view, this follows from the decision in Melville Dundas as well as being consistent with the reasoning in Integrated Building Services v PIHL.

(5) If the circumstances are as in paragraph (4) above but the adjudicator’s decision has, by agreement of the parties or operation of the contract, become final, the decision may be enforced by way of summary judgment (subject to the imposition of a stay). I reach this conclusion because I do not consider that the reasoning of the majority in Melville Dundas extends to this situation.

(6) There is no rule of English law that the fact that a party is on the verge of insolvency (‘vergens ad inopiam’) triggers the operation of bankruptcy set-off: see Melville Dundas, per Lord Hope at paragraph 33. However, the law in Scotland appears to be different on this point (perhaps because the Scottish courts do not enjoy the power to grant a stay in such circumstances).

(7) If a party is insolvent in a real sense, or its financial circumstances are such that if an adjudicator’s decision is complied with the paying party is unlikely to recover its money, or at least a substantial part of it, the court may grant summary judgment but stay the enforcement of that judgment.

Evidencing the Impecuniosity

8.16 The burden of proving the impecuniosity is on the party alleging it, who must adduce evidence of ‘a very real risk of future non-payment’.25 The assessment is to be carried out at the likely future date when repayment may be required which necessarily requires a degree of speculation.26 Notwithstanding the duty to cooperate, there is no obligation on the claimant to ‘give widespread disclosure’ of all of its financial information ‘so that the other party can see whether there is something which gives grounds for an application to stay’.27 Where there is no ‘direct evidence’ as to the claimant’s financial status, a court may conclude that if it acceded to a stay application, it would ‘drive a coach and horses through the adjudication scheme’ and ‘frustrate Parliament’s intention’.28

8.17 Judge Seymour considered the evidentiary aspects of an application for a stay in Rainford House Ltd v Cadogan Ltd (in administrative receivership) (2001) (Key Case)29 in which he stated:

11. So far as the question whether to grant a stay of execution is concerned, each case must depend upon its own facts. I agree … that it is for the applicant for any stay to put before the court credible material which, unless contradicted, demonstrates that the claimant is insolvent. However, in my judgment it is not necessary for the applicant for the stay to go further than to put before the court evidence as to the present financial position of the claimant, so that he does not need to shoulder some additional burden of predicting when any challenge to the correctness in fact of the determination of the adjudicator will be heard or of putting before the court positive evidence as to what the financial position of the claimant will then be. Further, I do not consider that the burden which the applicant for a stay bears is that of demonstrating beyond the possibility of error that the claimant will, come the time when the correctness or otherwise of the decision of the adjudicator is determined, be unable to repay the amount determined by the adjudicator to be payable. … [I]t is, in my judgment, appropriate when considering an application for a stay of execution in a case such as the present, to proceed on the basis that once the applicant for a stay has adduced apparently credible evidence which, if uncontradicted, shows that the claimant in the action is then insolvent,

(a) it is for the claimant, if it wishes the court not to draw the inference for which the applicant for the stay contends, to seek to contradict the evidence adduced on behalf of the applicant;

(b) in the absence of evidence to suggest that the position as it appears at the time the application is before the court is likely to alter the inference which should be drawn is that it will not.

8.18 It is clearly important to produce the right amount of evidence to persuade a court that a stay is warranted. In an attempt to overcome this hurdle, in Treasure & Son Ltd v Martin Dawes (2007) (Key Case),30 two forensic independent reports were obtained in support of Mr Dawes’ attempts to stay enforcement. Notwithstanding these creative (and expensive) avenues, the court refused to grant the stay as the claimant was neither insolvent nor bankrupt and there was no persuasive evidence that it would not be in a position to repay the monies in question in the event that an arbitrator came to a conclusion different from the adjudicator’s decision.

8.19 Depending on the allegations of impecuniosity levelled at the claimant in enforcement proceedings, it may wish to seek to defend its financial health through the introduction of its own evidence. Thus, in Avoncroft Construction Ltd v Sharba Homes (CN) Ltd (2008) (Key Case),31 the claimant introduced proof of a parent company guarantee, and the court declined to grant the stay.

Circumstances in which a Stay Is Unlikely to Be Granted

8.20 Even if the court considers that the impecuniosity threshold has been reached, it may not exercise its discretion to order a stay of execution. As identified in paragraph 26(f)(i) of Wimbledon v Vago (Key Case) (see 8.10 above), the courts will not grant a stay where the claimant company is not in a significantly worse financial position at the time it seeks summary judgment than at the time that the contract was made.32 This is because the defendants ‘got the result they contracted for and cannot now use the claimant’s ill-health to avoid judgment’.33 For example, where the claimant company was not even incorporated when the defendant contracted with it, the defendant was not granted a stay of execution, as it contracted ‘with [its] eyes open’ to the claimant’s ‘lack of value and creditworthiness’.34

8.21 The courts have also followed paragraph 26(f)(ii) in Wimbledon v Vago and have refused to grant a stay where non-payment of the sum awarded by the adjudicator materially caused or contributed to the claimant’s financial difficulties.35 Refusal to pay in accordance with an adjudicator’s decision can cause very real hardship for small contractors and may contribute to their problems in paying suppliers, subcontractors, and legal representatives.36

8.22 In Pilon Ltd v Breyer Group PLC (2010),37 Coulson J confirmed:

1. The question is whether the defendant’s non-payment of the sum found due by the adjudicator has caused the claimant’s poor financial position.

2. Allegations of the defendant’s non-payment of sums38 arising under other contracts between the parties was irrelevant.

3. Where the debts of the claimant are not linked to the defendant in any meaningful way, a stay may be granted.