EUROPEAN HUMAN RIGHTS LAW AND THE HUMAN RIGHTS ACT 1998

7

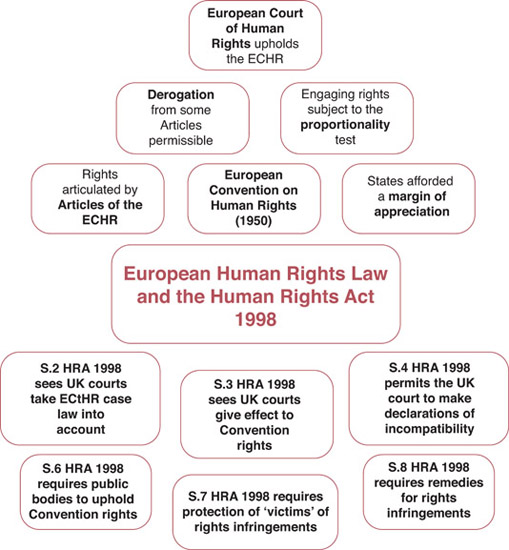

European human rights law and the Human Rights Act 1998

7.1 The European Convention on Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms

7.1.1 The Council of Europe was founded in 1949 with the goal of post-war harmonisation across Europe. The Council accepted the UN Declaration of Human Rights 1948 as a model for a European charter and the European Convention on Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (ECHR) came into force on 3 December 1953.

7.1.2 The Convention established a European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), which sits at Strasbourg. It may convene as a committee of three judges, as a chamber of seven, or in Grand Chamber of all 17 judges.

7.2 Particular rights from the ECHR and its Protocols

7.2.1 Applications to the Court may be brought by States, an individual, groups of individuals and non-governmental organisations. The applicant must be personally affected by the issue.

7.2.2 Under Article 35 of the Convention, an applicant cannot proceed to the ECtHR until all domestic remedies available are first exhausted. An application must be made within six months of the final decision of the highest court having jurisdiction.

| Article | Right |

| 2 | Right to life Allowable exceptions excuse unintentional death as result of violent situations, e.g. to quell riots, acting in self-defence but force used must be ‘no more than absolutely necessary’ |

| 3 | Freedom from torture, inhuman and degrading treatment |

| 4 | Freedom from slavery and forced labour Does not include compulsory labour as part of lawful detention |

| 5 | Right to liberty and security of person Applies except in accordance with lawful arrest or detention |

| 6 | Right to a fair trial before an independent and impartial tribunal Protects the presumption of innocence Provides for minimum rights to receive information and prepare defence Special circumstances can be justified where publicity would prejudice national security or the interests of justice, e.g. protection of juveniles |

| 7 | Prohibition of retrospective criminal law |

| 8 | Respect for private and family life Interference with this right by the State is permitted only if necessary in a democratic society including in the interests of: National security; Public safety; Economic well-being of the State; Prevention of disorder and crime; Protection of health and morals; and Protection of the rights and freedoms of others |

| 9 | Freedom of thought, conscience and religion Interference with this right by the State is permitted only if necessary in a democratic society including in the interests of: Public safety; Public health and morals; and Protection of the rights and freedoms of others The protection of the right to privacy is limited |

| 10 | Freedom of expression Interference with this right by the State is permitted only if necessary in a democratic society including in the interests of: National security; Territorial integrity; Public safety; Prevention of disorder and crime; Protection of health and morals; Protection of the reputation or rights of others; and Prevention of the disclosure of information received in confidence or to maintain the authority and impartiality of the judiciary |

| 11 | Freedom of assembly and association Interference with this right by the State is permitted only if necessary in a democratic society including in the interests of: National security; Public safety; Prevention of disorder and crime; Protection of health and morals; and Protection of the rights and freedoms of others |

| 12 | Freedom to marry and found a family Rights must be exercised according to the State’s laws on marriage |

| 13 | Right to an effective remedy |

7.2.3 Article 14 does not provide a substantive right but that the rights and freedoms of the Convention are to be enjoyed by all, regardless of race, age, sex, language or other classification. A case cannot be founded purely upon Article 14; discrimination on the application of a substantive right must be shown.

7.2.4 In addition to the Convention rights, there are Protocols that:

- • alter the machinery of the Convention; and

- • add rights to the Convention, which are optional and only come into force between ratifying States.

| Protocol | Coverage |

| First | Article 1 – right to peaceful enjoyment of possessions Article 2 – education Article 3 – holding of regular and free elections |

| Fourth | Article 1 – prohibits imprisonment for breach of contract Article 2 – right to freely move Article 3 – prohibits expulsion of nationals and provides for right to enter the country of nationality Article 4 – prohibits collective expulsion of non-nationals UK signed but has not ratified this Protocol Sixth Requires parties to restrict the application of the death penalty to times of war or ‘imminent threat of war’ |

| Seventh | Article 1 – right to fair procedures for lawfully resident foreigners facing expulsion Article 2 – right to appeal in criminal matters Article 3 – compensation for victims of miscarriages of justice Article 4 – prohibits the re-trial of anyone who has already been finally acquitted or convicted of a particular offence Article 5 – equality between spouses UK has not signed this Protocol |

| Twelfth | Applies the indefinite grounds of prohibited discrimination to the exercise of any legal right and to the actions and obligations of public authorities UK has not signed this Protocol |

| Thirteenth | Total abolition of the death penalty |

| Fourteenth | Permits the filtering of cases that have less chance of succeeding along with those that are similar to cases brought previously against the same State Case will not be considered admissible where an applicant has not suffered a ‘significant disadvantage’ Came into force on 1 June 2010 |

7.2.5 Some illustrative examples of ECtHR decisions on the scope of the substantive rights under the Convention in the context of the United Kingdom include:

| Article 2 | |

| Case | Decision |

| Paton v UK (1980) | Right to life begins at birth |

| McCannv UK (1996) | Inappropriate control and organisation over a covert military operation resulted in the ‘more than was absolutely necessary’ deaths of suspected terrorists |

| Pretty v UK (2001) | There is no right to assisted suicide |

| Evans v UK (2007) | The right to refuse an ex-partner the ability to use embryos does not violate Article 2 (or Article 8, see below) |

| Article 3 | |

| Case | Decision |

| East African Asians v UK (1983) | Immigration controls based on racial discrimination amount to degrading treatment |

| DvUK(1 997) | Deportation of an individual to a country lacking suitable health care that could result in their death violates the Article |

| Chahal v UK (1996) | A person cannot be forcibly returned to their country of origin when they are likely to face torture, inhuman or degrading treatment |

| A v Secretary of State for the Home Department (No. 2) (2005) | Evidence obtained by torture in another country cannot be used in the courts |

| Article 5 | |

| Case | Decision |

| Johnson v UK (1996) | Failure to release a mentally ill patient because of lack of suitable accommodation breaches the Article |

| T and Vv UK (1999) | Setting sentence periods without an opportunity for the lawfulness of the continued detention to be judicially reviewed breaches the Article |

| Murray v UK (1994) | The State must have ‘reasonable suspicion’ of an offence to justify detention |

| Caballero v UK (2000) | Automatic denial of bail for some offences breaches the Article |

| O’Harav UK (2001) | Arrested persons must be brought before a judge in a prompt and timely manner |

| Article 6 | |

| Case | Decision |

| Osman v UK (1998) | Striking out a negligence claim against the police on the grounds of public policy breached the Article |

| T and V v UK (1999) | Trying juveniles in an adult court violates the Article |

| Steel and Morris v UK (2005) | Denial of legal aid to defend a libel action brought by McDonald’s breached the Article |

| Article 8 | |

| Case | Decision |

| Dudgeon v UK (1982) | Prohibition under statute of homosexual acts between male adults in Northern Ireland amounted to a breach of the Article |

| Malone v UK (1984) | Tapping of a private telephone without a warrant breached the Article |

| McMichael v UK (1995) | If interference with family life is justified in the interests of a child, the family member’s rights must still be protected |

| Lustig-Prean and Beckett v UK (2000) | Banning homosexuals in the armed forces breached the Article |

| Gillan and Quinton v UK (2010) | Section 44 of the Terrorism Act 2000 was not in accordance with the law because the power to stop and search dispensed with the condition of reasonable suspicion |

| Article 10 | |

| Case | Decision |

| Sunday Times v UK (1979) | The common law on contempt of court was too imprecise and unsatisfactory to justify the granting of an injunction and this was a breach of the Article. The UK changed the law by passing the Contempt of Court Act 1981 |

| The Observer and The Guardian v UK (1991) | The continuation of injunctions against the publication of Spycatcher had breached the Article because they were no longer justifiable since the information was no longer confidential |

| Goodwin v UK (1996) | A court order under the Contempt of Court Act 1981 to disclose a journalist’s sources violated the Article |

7.2.6 Some more recent cases involving the United Kingdom in the ECtHR are addressed in Chapter 16 on human rights grounds of judicial review.

7.3 Derogation

7.3.1 Derogation by a State is not permitted in respect of all Convention rights. Only in specific circumstances (e.g. a state of emergency) can a State inform the Council of Europe that it will take steps that do not conform to its obligations. For example, in 2002 the United Kingdom entered a new derogation in respect of Article 5 in order to legitimise detention of non-nationals pending determination of their asylum status.

7.3.2 Reservations may be entered only before ratification. Under a reservation, the State will accept the obligations of a particular Convention right, subject to the application of its domestic legislation then in force.

7.4 The proportionality principle

7.4.1 The Convention itself makes reference to the need to uphold rights whilst ensuring that the community, the State and individuals are not thereby damaged.

7.4.2 The exercise of a right must therefore be proportionate to the effects of such exercise on others. Similarly, the response of the State to an administrative or legislative necessity must be proportionate to the desired outcome.

7.4.3 The application of the proportionality principle as a ground of judicial review is addressed in more detail in Chapter 16, Human rights grounds for judicial review, along with other considerations of the different steps in making human rights-based claims for judicial review.

7.5 The margin of appreciation

7.5.1 While a State has positive obligations under the Convention, the Council and the Court recognise that there should be a degree of discretion permitted, on the basis that each State is uniquely placed to gauge the necessity for limitations on Convention rights within its territory. This degree of discretion over engaging rights is known as the ‘margin of appreciation’ each State is afforded when the Court considers potential violations of the Convention by that State.