LEGAL STRUCTURES OF BUSINESS ORGANISATIONS

Legal structures of business organisations

AIMS AND OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter you should be able to:

Categorise private businesses in the UK according to legal structure

Categorise private businesses in the UK according to legal structure

Recognise unincorporated business organisation legal structures

Recognise unincorporated business organisation legal structures

Recognise incorporated business organisation legal structures

Recognise incorporated business organisation legal structures

Understand the different types of registered companies available

Understand the different types of registered companies available

Identify the key differences between private and public companies

Identify the key differences between private and public companies

Understand that not all public companies have shares listed on a stock exchange

Understand that not all public companies have shares listed on a stock exchange

Compare and contrast the main features of partnerships, LLPs and registered companies

Compare and contrast the main features of partnerships, LLPs and registered companies

Appreciate the variety of legal structures used in the social economy

Appreciate the variety of legal structures used in the social economy

Identify the special features that attach to community interest companies compared to ordinary registered companies

Identify the special features that attach to community interest companies compared to ordinary registered companies

Understand EU-level organisational legal structures introduced for use by businesses and in the social economy

Understand EU-level organisational legal structures introduced for use by businesses and in the social economy

This book is about business organisation law in the UK, specifically the law applicable to companies registered under the Companies Acts formed to own and conduct one or more businesses run for profit. The aim of this chapter is to put business organisations structured as registered companies into context.

First, profit-making business organisations are categorised according to their legal structure and size. The appropriateness of using the legal structure adopted by a business organisation to determine the applicability of certain mandatory laws such as public disclosure is questioned. The different legal structures through which businesses may be conducted in the UK are then examined, looking first at unincorporated, then incorporated business forms.

Due to the increasing political, social and economic importance of not-for-profit organisations, or ‘social enterprises’, interest is growing at both national and European Union (EU) level in the legal structures used in this ‘third sector’ or ‘civil society’. Although detailed consideration of these legal structures is outside the scope of this book, it is important to be aware of this development and the penultimate section of this chapter looks at some of the more popular legal structures used in the UK in the third sector. Finally, in the last section of this chapter, we look at EU initiatives in relation to business organisations and civil society entities.

2.2 Categorising private businesses in the UK

2.2.1 Categorisation of private businesses by legal structure

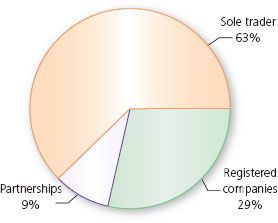

According to statistics published by BIS there were approximately 4.9 million private business enterprises in the UK at the beginning of 2013, a figure that excludes government and non-profit organisations. Of these, 63 per cent are sole traders, less than 9 per cent are partnerships and almost 29 per cent are registered companies.

A number of difficult issues arise in attempting to achieve accurate and comparable statistics which render the figures that follow indicative rather than definitive numbers. Subject to this proviso, if we focus on private business enterprises in which more than one person is involved, either as an owner or employee, the total number of enterprises drops from 4.9 million to around 1.2 million, approximately 25 per cent of business enterprises. This reflects two key facts. First, a fact that might not come as a surprise is that of 3.1 million sole traders, only 9 per cent employ another person or persons. What might come as a surprise, however, is that over half of all companies (57 per cent) are ‘one man band’ companies, that is, they have only one person, the owner, working in them. The term ‘working’ is used here rather than ‘employed’ because as a matter of law the owner, who will be a shareholder and a director, may or may not also be an employee of the company.

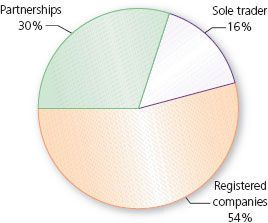

When one man band enterprises are excluded (70 per cent of the total population of businesses), the proportion of the business enterprises using each of the three most popular legal structures changes considerably. Companies are the most popular legal structure, at 54 per cent of the total, followed by partnerships at 30 per cent and sole traders make up 16 per cent of the total.

The limited liability partnership (LLP) does not feature in the national statistics referenced above. The LLP is a legal structure available only since 2001 and whilst as at March 2006 approximately 17,500 were registered, that figure has more than tripled to stand at 56,000 as at May 2014. Notwithstanding the limited number the LLP is an important structure to understand, not least because of its popularity amongst professionals, including lawyers. The LLP is the legal structure of choice for firms of accountants and solicitors. It is discussed at section 2.4.2.

Figure 2.1 Private business enterprises in the UK 2013.

Figure 2.2 Private business enterprises with two or more persons in the UK 2013.

2.2.2 Categorisation of private businesses by size

Business enterprises are increasingly considered in terms of micro, small and medium enterprises (SMEs) on the one hand and large enterprises on the other with increasing political focus on SMEs. Support for SMEs is one of the European Commission’s priorities for economic growth, job creation and economic and social cohesion. Eligibility for EU measures such as community programmes, grants and loans very often depends upon an enterprise meeting the SME criteria. In the EU, SMEs are believed to account for more than 99 per cent of all business enterprises and 67 per cent of all employment. The corresponding figures in the UK are 99.9 per cent and 59 per cent, although, again, care must be taken in interpreting the figures as they are not directly comparable due to different underlying methodologies used to compile them. What appears to be clear is that in the twenty-first century to date, both in the UK and the EU, new jobs have been created primarily by SMEs, not by large companies.

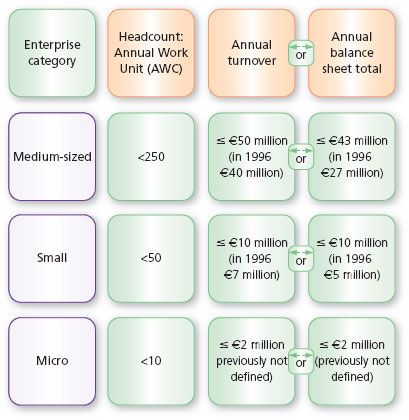

No single consistent definition of the term SME exists. Where the term is used, the meaning should always be confirmed. For grant and loan purposes the EU defines SME as ‘micro, small and medium-sized enterprises’ (making it an odd abbreviation since the introduction of the ‘micro’ category) (see Commission Recommendation of 6 May 2003 (2003/361/EC) OJ L 124 p. 36).

The three criteria used by the EU to assess whether an enterprise is micro, small or medium-sized for these purposes are the number of employees (or headcount), the annual turnover (the sum received for goods and services in a year) and the annual balance sheet total (the total value of the assets or property of the enterprise, less the amount it owes). An enterprise must meet the employee threshold and one of the other two criteria thresholds to come within a particular category. Any enterprise that employs 250 or more individuals is a large enterprise, not an SME, regardless of its income or assets. The thresholds current as at April 2012 are set out in Figure 2.3.

Figure 2.3 EU definition of SME for loan and grant purposes from 1 January 2005.

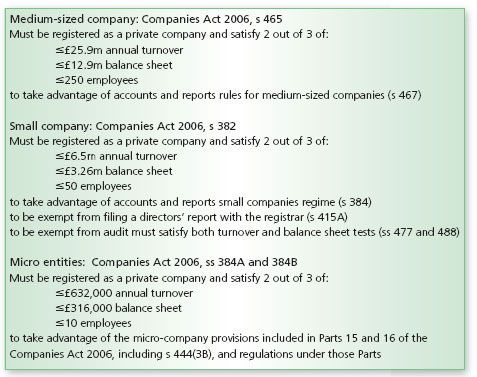

The EU also classifies businesses into micro, small and medium-sized undertakings for the purpose of accounting and reporting obligations (see Directive 2013/34/EU), for which the thresholds are different from those for SME enterprises described above. The thresholds relevant to accounting are reflected in Figure 2.4 as they underpin the UK figures in the Companies Act 2006 and UK regulations implementing the relevant EU accounting directives (including the Companies Act 2006 (Amendment) (Accounts and Reports) Regulations 2008 (SI 2008/393), the Large and Medium-sized Companies and Groups (Accounts and Reports) Regulations 2008 (SI 2008/410) (as amended), the Small Companies and Groups (Accounts and Reports) Regulations 2008 (SI 2008/409) (as amended) and the Small Companies (Micro-Entities’ Accounts) Regulations 2013 (SI 2013/3008)).

2.2.3 Categorisation relevant to determining applicable laws

Size, to some extent, determines the legal rules applicable to a company registered under the Companies Acts and to an LLP. The Companies Act 2006, for example, applies less rigorous public disclosure and audit requirements to micro entities and small and medium-sized companies, as those terms are defined in the Companies Act 2006 (as amended). The requirements to qualify as a micro entity or small or medium-sized company for these purposes are set out in Figure 2.4.

Figure 2.4 Micro entities and small and medium-sized companies for Companies Act 2006 purposes.

Rather than size, however, by far the more important factor determining the legal rules that apply to a private business is the legal form it takes, and, within the category of registered companies limited by shares, whether it is a private company (Ltd or Limited) or a public company (plc). This key distinction is drawn at various points throughout this book and the differences are summarised in Table 2.1 later in this chapter.

Increasingly, laws are being developed to regulate companies with shares traded on stock markets. This makes it very important to distinguish between those companies with, and those without, shares traded on a stock market. Great care needs to be taken here, as a number of terms are used in law to determine the scope of application of particular legal provisions. ‘Quoted company’ (s 385), ‘traded company’ (s 360C) and ‘listed company’ come to mind (all of which terms are considered in section 2.4.1). Always check to which type of company particular laws apply.

Also, be aware that the use of a term in law may be very different from its general (non-legal) usage. For example, in general usage, the term ‘quoted’ refers to shares traded on any stock market. The London Stock Exchange, for example, defines shares listed on AIM (the second most important market for shares in London) as ‘quoted’. In contrast, the term ‘quoted company’ as defined in the Companies Act 2006, includes companies with shares traded on the Main Market of the London Stock Exchange (and certain other markets) but does not include companies with shares traded on AIM. Figure 2.6, which appears later in this chapter, represents the Companies Act 2006 definition of quoted company figuratively.

The appropriateness of legal-form based regulation is open to question. For example, why should a large partnership be subject to no public disclosure rules when a similarly sized company is required to make extensive information, including details about its owners, directors and share capital, and annual accounts and reports available to the public? It is noteworthy that the first company statute, the Joint Stock Company Act 1844, required any new business organisation with more than 25 members to register as a company, a threshold lowered to 20 by the Joint Stock Company Act 1856. Large business organisations (size being gauged by reference to the number of owners) were thereby subject to public disclosure requirements. The size limit of 20 on partnerships (the only effective alternative legal structure) was eroded by more and more exceptions over the years until it was finally abolished in 2002. Today, there is no limit on the number of partners a partnership can have.

Public disclosure to enable scrutiny is acknowledged to be an important and effective tool to drive best practice in business organisation governance in the public interest. The public interest is increasingly concerned with business organisation governance, environmental protection, the impact of business on the community, and the interests of stakeholders in businesses other than owners and creditors. As the interests served by public disclosure are expanded, it may be more appropriate for disclosure obligations to be triggered by size of business rather than by the legal structure adopted as this would ensure that large businesses are subjected to adequate scrutiny.

It is arguable that size is a more appropriate basis on which to impose a more onerous legal regime, rather than legal rules being triggered based on registration as a private or public company or based on a company being quoted, traded or listed. Quoted companies are subject to the most onerous narrative reporting under the Companies Act 2006, for more on which, see Chapter 17. As company law becomes more concerned with a variety of stakeholders in addition to shareholders and creditors, the public/private, quoted/unquoted, traded/untraded and listed/unlisted company distinctions may be eclipsed by categorisation by size as the trigger for the application of more onerous company laws.

A current and important relevant trend before the credit crunch was for private equity firms to acquire larger and larger companies. If the company acquired is a quoted company, its shares may be withdrawn from being traded on a stock market (usually the Main Market of the London Stock Exchange), and removed from the official list. This removes the company from both the higher level of public disclosure imposed on quoted companies by the Companies Act 2006 tiered disclosure regime and the public disclosure obligations imposed by securities regulation on companies with shares traded on a stock market, the result being less effective public scrutiny. An example of this was the acquisition in June 2007 of Alliance Boots plc, the company that owns the Boots high street chain of chemists, by AB Acquisitions Limited, a company controlled by private equity funds. Since its acquisition, its shares are no longer traded on a stock market, it is no longer a quoted, traded or listed company, and Alliance Boots plc has been re-registered as a private company: Alliance Boots Ltd.

2.3 Unincorporated business organisation legal structures

Unincorporated organisations are organisations that are not persons, in the eyes of the law, separate from their members. They are not corporate entities or artificial legal persons. Businesses run for profit that are not organised as corporate entities almost all take the form of sole traders or partnerships. Each of these business forms is considered in this section. Unincorporated organisations that are not sole traders or partnerships are often referred to as ‘unincorporated associations’. As running a business to make profits is not usually the principal purpose of these organisations (most of them are clubs or co-operatives), they are considered later in this chapter along with other social enterprise private legal structures (see section 2.6).

sole trader

An individual who is in business on his own account, i.e. he is not in partnership, nor does he trade through a corporate body

No ‘core’ business organisation law exists relevant to sole traders or ‘sole practitioners’ (the term preferred by professionals) because there is no organisation to regulate. A sole trader is an individual who offers goods or services to others in return for payment. In the context of distinguishing a sole trader from an employee, a sole trader is referred to as an ‘independent contractor’.

The individual who is the sole trader is the party to contracts, owns all the property he or she uses in the course of trade or business, and receives all the income and profits from the business. A sole trader can contract with individuals to help in the business, whether by entering into a contract for services with an independent contractor or a contract of employment (a contract of service) with an employee. In the latter case, the individual sole trader is the employer. Approximately 9 per cent of sole traders employ others in their business.

The individual who is the sole trader is also the person sued if anything goes wrong in the course of the business. If a judgment is obtained against the individual, all of his or her assets (whether personal or used in the business) are available to settle or pay that judgment debt.

No legal person, separate from the individual, is created, therefore the sole trader carries on an unincorporated business. The individual cannot be an employee of the business because he cannot contract with himself. Both of these points mean that, in contrast to establishing a company through which to conduct a business, there is little opportunity for a sole trader to minimise his or her tax liability. A sole trader is taxed as a self-employed person and the profit from carrying on the business is subject to income tax. If the individual has taxable income from outside the business, perhaps interest on his or her savings in a Building Society, the business profits are added to that income and the rates of tax (50 per cent, 40 per cent and 20 per cent) are applied to the total income.

Setting up in business as a sole trader is easy. The sole trader simply needs to register as self-employed with Her Majesty’s Revenue & Customs (HMRC). Any laws applicable to the particular type of business or practice in which the sole trader is involved also need to be complied with. A sole trader who employs others must register for PAYE purposes and if earnings of the business are expected to exceed the relevant threshold (£81,000 per annum in 2014–15) a sole trader will also need to register for value added tax (VAT) purposes. No information about a sole trader’s business needs to be made available to the public: a sole trader has financial and business privacy.

Individuals who wish to own and manage a business on their own can choose to conduct that business as a sole trader or through a company. The decision of an individual to establish a company may, however, be customer led, and, to this extent, less a choice of the individual rather than a trading necessity. Potential customers, preferring to contract with a company to provide the services of an individual rather than contracting directly with that individual, may exclude sole traders from consideration when deciding to whom to award a contract. The reasoning behind this practice, prevalent in the IT industry, is that customers do not wish to incur the consequences of an individual being found to be an employee. An employee has far more rights against the customer/employer than arise out of a contract for services with a service delivering company. Furthermore, an employer must pay employer national insurance (13.8 per cent in 2014–15) on the earnings of an employee, and incur the administrative cost and inconvenience of deducting employee national insurance contributions and income tax from an employee’s earnings and paying the deducted sum to HMRC under the ‘pay as you earn’ (PAYE) system.

partnership

The relation which subsists between persons carrying on a business in common with a view of profit

General partnerships

Partnership is a legal relationship defined in the Partnership Act 1890 (in this section, ‘the Act’). The Act has set out the basic structure of partnership law with no significant substantive change for over a century. There are no necessary formalities required to create a partnership.

SECTION

‘Partnership Act 1890, section 1(1)

Partnership is the relation which subsists between persons carrying on a business in common with a view of profit.’

Whether or not a partnership exists is decided by applying the statutory test to the facts. Whether an express (written or oral) or implied agreement is entered into or not, if two or more persons carry on a business together (‘in common’), with the intention of making a profit, a partnership will exist because the arrangement falls within s 1(1) of the Act. The relationship between the members of a company is not a partnership, a point put beyond doubt by s 1(2).

Section 2 contains rules to help to decide whether or not a partnership exists. These rules deal with sharing profits (prima facie evidence of partnership, s 2(3)), and sharing income and ownership of property (neither, in themselves, enough to evidence a partnership, ss 2(2) and 2(1) respectively). The Act defines partners collectively as a firm (s 4).

The Act continues, setting out internal rules governing relations between the partners themselves, and external rules governing relations between the partnership and those dealing with the partnership. Most internal rules in the Act are not mandatory rules but default or ‘opt-out’ rules, that is, rules that apply unless the partners agree otherwise. Agreement otherwise can be oral or evidenced by behaviour but is most commonly evidenced by a written contract between the partners setting out the main terms on which the partnership is to operate. Written partnership agreements range from very simple to massively detailed documents. Law firm partnership agreements are typically very long and involved.

Two important examples of simple default rules regularly opted out of and in many cases replaced by long and complex provisions, are (1) the capital and profit sharing rule, and (2) the management rule, both found in s 24 of the Act.

SECTION

‘Partnership Act 1890, s 24

(1) All the partners are entitled to share equally in the capital and profits of the business, and must contribute equally towards the losses whether of capital or otherwise sustained by the firm …

(5) Every partner may take part in the management of the partnership business.’

In law, partnerships are not legal persons or entities distinct from the partners. A partnership is an unincorporated association. A partnership cannot own legal property: the property is owned by the partners (using a trust in many cases to vest the legal title in a limited number of partners to be held for all partners). Nor can a partnership enter into a contract. Contracts, even those which appear on the face of the contractual document to be with a firm, or the partnership because the firm is named as the party to the agreement, are in fact contracts with the individuals who are the partners in the firm. The Law Commission has described the unincorporated legal status of partnerships as ‘a throwback to the nineteenth century’ and an anomaly which it considers it long past time to end. As discussed later in this section, however, the government has chosen not to implement the Law Commission’s proposals for partnerships to be incorporated organisations.

The unincorporated status of partnerships makes the external rules that apply between partners and third parties critically important. In default of agreement to the contrary, partners have authority to bind the other partners in the firm to contracts: partners are agents of one another. Moreover, s 9 confirms that every partner in a firm is liable, jointly with the other partners, for all debts and obligations of the firm incurred whilst he is a partner. Section 10 extends this liability to cover wrongful acts or omissions of any partner acting in the ordinary course of the partnership business. A partner’s liability is unlimited (although see limited partnerships, below, for the special case where a non-managing partner can limit his contribution to the sum invested in the partnership).

Unlike companies and LLPs, partnerships are not subject to public disclosure obligations. This is an important factor for those who choose to operate their business as a partnership. With the abolition of the restriction on the size of partnerships, it is arguable that, for large partnerships, this absence of public disclosure should be revisited.

A partnership is automatically dissolved every time there is a change of partner, a state of affairs described by the Law Commission in 2003 as, ‘far removed from the ordinary perceptions of those involved’.

QUOTATION

‘Any change in the membership of a firm, whether the withdrawal of a partner or the admission of a new partner, “destroys the identity of the firm”. The “old” firm is dissolved. If the surviving partners continue in partnership (with or without additional partners) a “new” firm is created. The new firm can take over the assets of the old one and assume its obligations. This involves a contractual arrangement between members of the old firm and the new firm, to continue the old firm’s business. In addition, the transfer of an obligation will normally require the consent of the creditor. Continuing a partnership’s business in this way does not continue the partnership itself. Even an agreement in advance that partners will continue to practise in partnership on the retirement of one of their number does not prevent the partnership which practises the day after the retirement from being a different partnership from that in business on the previous day.’

Law Commission, ‘Partnership Law’ (Law Com No 283, 2003) at para 2.6

One of the main aims of this chapter is to draw attention to distinguishing features between partnerships and registered companies. Transferability of shares is a key characteristic of registered companies. Shareholders are able to sell their shares, that is, they can, in effect, withdraw their investment in the company, without affecting the company’s financial position. The shareholder exits the company by receiving his investment back from the new owner of the shares. Transferability exists for shareholders of companies with publicly traded shares but is not always a reality for the owner of private company shares for which it can be very difficult to find a buyer. This ability of the company to continue unaffected by changes in ownership is in stark contrast to partnerships. Or at least it is in theory. In practice, tax rules combined with appropriate provisions in partnership agreements can mean that whilst in theory a change in partners operates to terminate a partnership, in fact, the partnership business is not wound up and the business continues largely as before, with one less or one more partner.

Limited liability is often portrayed as the principal distinction between partnerships and registered companies. More recently, however, business organisation law theorists have turned their attention to ‘entity shielding’ or, as it is also called, ‘affirmative asset partitioning’. Entity shielding describes the situation in which the assets or property of a business organisation are protected from the claims of the owner’s personal creditors. Entity shielding is strong in registered companies. The assets are owned by the company and if a shareholder owes money to a personal creditor, that creditor cannot enforce the debt against the company. Nor can the shareholder force the company to wind up and pay out the value of his shares to him to enable him to pay his creditors. The company is protected as a going concern.

In contrast, the personal creditors of a partner can demand a payout of the partner’s share of the assets to meet the debts that the partner, in his personal capacity, owes to them. The only entity shielding that exists in the context of a partnership is ‘weak’ entity shielding in that the claims of personal creditors of a partner are subordinated to the claims of the creditors of the partnership: the creditors of the partnership must all have been paid in full before partnership assets can be used to pay personal debts of any of its partners. The different degrees of entity shielding in partnerships and companies has been described as an even more important distinction than limited liability (Hansmann, Kraakman and Squire 2007).

Following detailed review, comprehensive proposals for reform of partnership law, including a draft Bill, were put forward in 2003 by the Law Commission (see Law Com No 283). The most significant aspect of the proposals was that partnerships, whether general or limited (on which see below), should be separate persons, i.e. incorporated business organisations. Note, however, that the Law Commission did not propose limited liability for partners. Even if the proposals were to be adopted, partners would remain personally responsible, without limit, for the debts and other liabilities of the partnership.

Following DTI (now BIS) consultation on the economic impact of the proposals, in July 2006, the government announced its decision not to implement the proposals in respect of general partnership law ‘for the moment’. As at April 2012, no steps had been taken to implement the proposals in either England or Scotland in relation to general partnerships.

limited partnership

A partnership having one or more but not all limited partners, i.e. sleeping partners whose liability in the event of the partnership’s insolvency is limited to the amount that such partner has agreed to contribute

Limited partnerships

Limited partnerships are unincorporated firms provided for by the Limited Partnership Act 1907. They should not be confused with limited liability partnerships (LLPs). LLPs are incorporated entities provided for by the Limited Liability Partnership Act 2000 and are considered at section 2.4.2.

Limited partnerships are partnerships with at least one general partner and one limited partner, although there can be more of each type of partner, who contribute an agreed sum to the partnership and are not liable for the debts and obligations of the firm beyond that amount. Limited partners may not participate in management of the partnership and have no power to bind the firm.

Limited partnerships must be registered at Companies House and the registrar of companies issues a certificate of registration. The names of all of the partners (general and limited) and the sums contributed by limited partners are available for public inspection but there is no requirement for a limited partnership to file accounts. Approximately 1,000 limited partnerships per annum have been registered in recent years and as at the start of 2014, just under 24,000 limited partnerships were registered at Companies House. Since 1987 (when certain tax guidelines were agreed to by HMRC), limited partnerships have been popular with private equity firms for use as venture capital funds to acquire companies. Like general partnerships, limited partnerships are fiscally transparent, meaning that they are not treated as entities distinct from the partners for tax purposes.

The government’s initial indication, in 2006, that it proposed to implement the Law Commission proposals that limited partnerships should become legal entities led to a legislative proposal, in 2008, to substantially rewrite the Limited Partnership Act 1907. As a result of the consultation, very few of the changes were found to be unequivocally supported resulting in BIS adopting what it describes as a ‘modular approach’ to reform. The ensuing Legislative Reform (Limited Partnerships) Order 2009 (SI 2009/1940) effected very limited changes, the two main changes being making a certificate of registration conclusive evidence that a limited partnership has been formed at the date shown on the certificate; and introduction of a requirement that all new limited partnerships include ‘Limited Partnership’ or ‘LP’ or equivalent at the end of their names. Further expected reforms as part of a programme of modernising limited partnership law have not emerged at the time of writing but in the 2013 Budget the government stated its intention to carry out further consultation, particularly in relation to the potential for those setting up limited partnerships to elect to have separate legal personality.

Quasi-partnership companies

‘Quasi-partnership company’ is not a legally defined term. Company law sometimes acknowledges the fact that a business that is owned and conducted by a registered company has been:

established with partnership expectations, including, in particular, the expectation that all owners are entitled to participate in management; and

established with partnership expectations, including, in particular, the expectation that all owners are entitled to participate in management; and

run by the owners as if it were a partnership, for example, by all owners taking a part in management.

run by the owners as if it were a partnership, for example, by all owners taking a part in management.

Recognition of these characteristics has led judges to develop special rules for such ‘quasi-partnership’ companies. Three areas of company law where this is the case are:

enforcement of a company’s articles of association, specifically, the willingness of the court to permit members of a quasi-partnership company to sue each other directly to enforce the articles of association (Rayfield v Hands [1960] Ch 1);

enforcement of a company’s articles of association, specifically, the willingness of the court to permit members of a quasi-partnership company to sue each other directly to enforce the articles of association (Rayfield v Hands [1960] Ch 1);

Companies Act 2006, s 994 petitions, specifically the willingness of the court to grant a remedy based on a finding that even in the absence of any breaches of rights, the affairs of a quasi-partnership company have been conducted in a manner that is unfairly prejudicial to the interests of one or more members;

Companies Act 2006, s 994 petitions, specifically the willingness of the court to grant a remedy based on a finding that even in the absence of any breaches of rights, the affairs of a quasi-partnership company have been conducted in a manner that is unfairly prejudicial to the interests of one or more members;

Insolvency Act 1986, s 124 applications to wind up a company based on it being just and equitable to do so.

Insolvency Act 1986, s 124 applications to wind up a company based on it being just and equitable to do so.

2.4 Incorporated business organisation legal structures

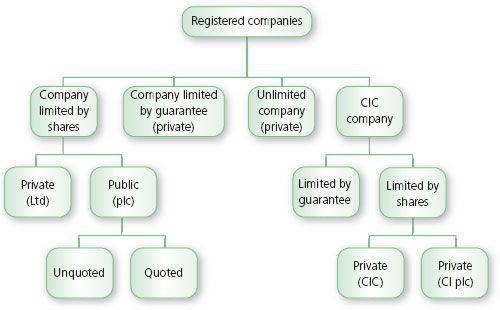

As seen above in section 2.2, if single member businesses are excluded (on the basis that they are not really ‘organisations’), the registered company, the focus of this book, is the most popular legal structure for business organisations in the UK. The types of companies that can be registered in the UK are displayed in Figure 2.5.

Figure 2.5 Types of registered companies.

This book focuses on companies limited by shares, both public and private. Companies limited by guarantee and unlimited companies are dealt with very briefly immediately below and community interest companies (CICs) are considered along with other social enterprise private legal structures (see section 2.6.3).

company limited by guarantee

A company the articles of which contain an undertaking by members to contribute a specified amount on a winding up towards the payment of its debts and the expenses of winding up

Companies limited by guarantee

Section 3(1) of the Companies Act 2006 states that a company is a limited liability company if the liability of its members is limited by its constitution. The liability of members may be limited by shares or limited by guarantee. A company is limited by guarantee if the liability of its members is limited to the amount specified in the articles that the members undertake to contribute to the assets of the company in the event of the company being wound up (s 3(3)).

Companies limited by guarantee are not commonly used in business. They are all private companies but a separate set of Model Articles for Companies Limited by Guarantee has been enacted, alongside those for private and public companies limited by shares (see the Companies (Model Articles) Regulations 2008 (SI 2008/3229)). Traditionally, companies limited by guarantee have been the registered company of choice for charitable companies (meaning companies registered under the Companies Acts with exclusively charitable objects). A new form of incorporated organisation is now available for charities, the charitable incorporated organisation (CIO). Developed to avoid the double burden that charitable companies have long endured, of having to register and file documents with both the Charity Commission and the registrar of companies, the CIO is expected to prove more popular than the company limited by guarantee (CIOs are considered below under social enterprise legal structures, at section 2.6.2).

Interestingly, Network Rail Ltd is a private company limited by guarantee. Formed in 2002 to take over Railtrack and responsibility for the UK’s rail network, it is a not-for-profit organisation that receives significant funds from the government. Nonetheless, it asserts on its website that it ‘operates as a commercial business’ and that the board runs the company ‘to the standards required of a publicly listed company’. Notwithstanding this, in September 2014, Network Rail Ltd will begin to be treated as a central government body (rather than a private body). This has been defended as a reclassification for statistical purposes, based on the fact that only the government bears any significant risk in relation to the company.

unlimited company

A company, the liability of whose members to contribute on a winding up to the company, to enable it to pay it debts, is not limited, by shares, guarantee or otherwise

private company

A registered company that is not a public company

public limited company

A company registered as a public company the name of which ends with the letters plc (or the words represented by those letters in full)

Unlimited companies

Unlimited companies, which must be private companies, are similarly uncommon in business. They are companies, the liability of whose members to contribute on a winding up to the company to enable it to pay its debts is not limited. They sometimes occur in business contexts as part of a tax planning structure due to some overseas tax authorities (including the US revenue service) regarding them as tax transparent, or ‘flow-through’ entities, i.e. ignoring them for tax purposes. In the event of a winding up, the members of an unlimited company are required to contribute sums to the company sufficient for payment of its debts and liabilities (Insolvency Act 1986, s 74(1)).

Companies limited by shares

Companies limited by shares have shareholders who own shares in the company. The concept of ‘limited’ is explored in the next chapter, at section 3.5. Essentially, a company is limited by shares if the liability of its members is limited to the amount, if any, unpaid on the shares held by them (s 3(2)). This limit must be set out in the constitution of the company, in the articles of association, and can be found in Article 2 of the relevant model articles. Accordingly, shareholders of a limited company are not required to contribute sums to the company sufficient for payment of its debts and liabilities but are simply required, when called upon to do so, to pay to the company any amount unpaid on the shares held by them.

Companies limited by shares may be public companies or private companies. The principal legal difference between public (plc) and private companies (Ltd or Limited) is that public companies may offer their shares to the public. A private company may not offer its shares to the public (Companies Act 2006, s 755). The main differences between public and private limited companies are set out in Table 2.1.

Certain sections of the Companies Act 2006 are applicable to some public companies (plcs) and not others. Two subdivisions of public companies relevant to the application of the Act are quoted and unquoted companies (s 385) and traded and untraded companies (s 360C).

Quoted companies

Quoted company is the term used in the Companies Act 2006 to identify registered companies with (in simple terms) equity shares traded on a UK or other EEA regulated stock market or one of the two most famous US stock markets, the New York Stock Exchange and NASDAQ (see Companies Act 2006, s 385 for the precise definition of quoted company). Quoted companies are illustrated diagrammatically in Figure 2.6. Important requirements of the Act apply only to quoted companies.

Traded companies

The traded company concept introduced into the Companies Act 2006 with effect from August 2009 as part of implementation in the UK of the Shareholder Rights Directive (2007/36/EC) (by the Companies (Shareholders’ Rights) Regulations 2009 (SI 2009/1632)) is a company with shares that carry the right to vote at a general meeting admitted to trading on a UK or other EEA regulated market (s 360C). It is relevant to shareholder resolutions and meetings.

Companies Act 2006 | |

The name of a public limited company must end with ‘plc’ or ‘public limited company’ and the name of a private limited company with ‘Ltd’ or ‘Limited’. | ss 58 and 59 |

Ltds cannot offer shares to the public. | s 755 |

Ltds can have one director, plcs need a minimum of two. | s 154 |

Ltds can make board decisions informally outside board meetings, plcs must use the directors’ written resolution process to take a decision outside a board meeting. | Model Articles 8 (Ltds) and 17 (plcs) |

No authorised minimum nominal value of allotted share capital for Ltds, £50,000 for plcs of which a minimum of 25% must be paid up. | ss 761 and 763 |

Plcs need a trading certificate before they can do business or exercise any borrowing powers. | s 761 |

A different set of model articles exists for private companies limited by shares and public companies. | s 19(2) and regulations 1 made thereunder |

Ltds need not hold AGMs; they only need meetings to remove directors pursuant to s 168 or remove auditors pursuant to s 510. | n.a. |

Ltds need not have a company secretary. | s 270 |

Ltds can pass shareholder written resolutions. | ss 288–300 |

Ltds can give financial assistance for the purchase of their own shares. | n.a. |

Ltds can purchase and redeem shares out of capital. | s 710 |

Ltds can reduce their share capital without court approval by special resolution and a solvency statement. | ss 641–643 |

Ltds can, if they meet the criteria, qualify for the micro entity, small or medium 1 companies regimes for accounts and reports and, if micro or small, for exemption from audit; plcs do not qualify for either. | ss 384, 384A and 478 s 381 (accounts) s 477 (audit) |

Table 2.1 Key legal differences between private (Ltd) and public (plc) limited companies.

Somewhat unhelpfully, the term traded company was already present in s 146 of the Act, for which purpose it simply means ‘a company whose shares are admitted to trading on a regulated market’. Section 146 enables a person who owns shares on behalf of another to nominate the beneficial owner as the person to receive information from the company, that is, to have ‘information rights’.

UK Listing Authority or UKLA

The Financial Conduct Authority when it acts as the competent authority under Part VI of FSMA 2000, i.e. the UK’s securities regulator