DIRECTORS’ DUTIES: CONFLICT OF INTEREST DUTIES

Directors’ duties: Conflict of interest duties

AIMS AND OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter you should be able to:

Distinguish:

Distinguish:

a director contracting (or having an interest in a contract) with his company

a director contracting (or having an interest in a contract) with his company

other conflict of interest situations

other conflict of interest situations

Understand the scope and operation of the two general conflict of interest duties:

Understand the scope and operation of the two general conflict of interest duties:

duty to avoid conflicts of interest (s 175)

duty to avoid conflicts of interest (s 175)

duty not to accept benefits from third parties (s 176)

duty not to accept benefits from third parties (s 176)

Identify director/company transactions for which shareholder approval is required

Identify director/company transactions for which shareholder approval is required

Identify when a director is required to declare his interest in a transaction to the board of directors

Identify when a director is required to declare his interest in a transaction to the board of directors

Recognise that the acts of a director may constitute breach of more than one duty

Recognise that the acts of a director may constitute breach of more than one duty

Analyse a fact situation and identify:

Analyse a fact situation and identify:

the behaviour of each director involved

the behaviour of each director involved

the directors’ duties that may have been breached by each director

the directors’ duties that may have been breached by each director

any statutory provisions governing company contracts with directors or persons connected with directors that may have been contravened

any statutory provisions governing company contracts with directors or persons connected with directors that may have been contravened

As indicated in the introduction to Chapter 11, this chapter covers two essential parts of our study of directors’ duties and the key statutory provisions governing company contracts with directors and persons connected with directors. The overall scheme of our study is as follows:

legislative reform (Chapter 11);

legislative reform (Chapter 11);

to whom the duties are owed (Chapter 11);

to whom the duties are owed (Chapter 11);

management duties (Chapter 11);

management duties (Chapter 11);

conflict of interest duties (Chapter 12);

conflict of interest duties (Chapter 12);

statutory provisions governing company contracts with directors and persons connected with directors (Chapter 12);

statutory provisions governing company contracts with directors and persons connected with directors (Chapter 12);

remedies and relief for breaches and contraventions (Chapter 13);

remedies and relief for breaches and contraventions (Chapter 13);

‘Conflict of interest duties’, as that term is used in this book, are the duties imposed on directors primarily to discourage them from acting not only in their own self-interest but also in the interest of any person other than the company, including a person to whom they may also owe a duty. Arguably the duty in s 173 to exercise independent judgment, considered in Chapter 11, would be better placed in this chapter, as a conflict of interest duty, based on its role in regulating a director faced with duties both to the company and a third party (often the director’s nominating shareholder). Its inclusion in the previous chapter, as a management duty, emphasises its role in requiring a director to actually exercise his judgment in the course of management, rather than abdicating responsibility.

The essential learning point is that directors’ duties are cumulative. A single act can be evidence of breach of a number of different duties. Section 179 states clearly, ‘more than one of the general duties may apply in any given case’.

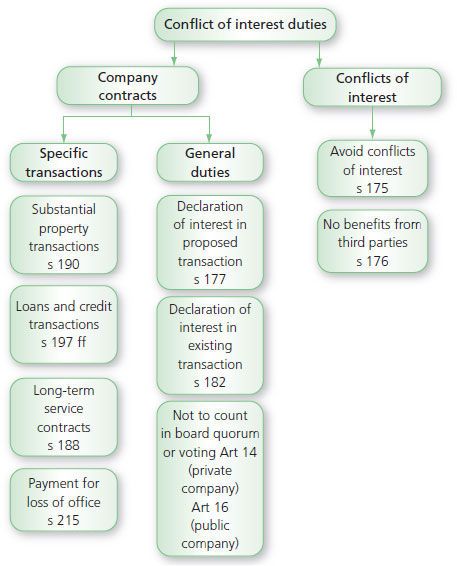

Duties regulating self-interested actions by directors fall into two categories: duties in relation to conflicts of interests and duties in relation to contracting with the company. Each category contains general duties. Additional statutory provisions govern specific types of contracts directors enter into with their companies. An overview of conflict of interest duties and key statutory provisions governing company contracts with directors and persons connected with directors can be seen in Figure 12.1. In this chapter we deal with the two general duties governing directors’ conflicts of interest that do not involve company contracts before turning to the duty imposed on directors to disclose interests in company contracts and specifically regulated company contracts.

Figure 12.1 Directors’ conflict of interest duties.

12.2 Directors’ conflicts of interest

Directors’ conflicts of interests are governed by two general duties, the duty to avoid conflicts of interest (s 175) and the duty not to accept benefits from third parties (s 176).

12.2.1 Duty to avoid conflicts of interest

SECTION

‘175 Duty to avoid conflicts of interest

(1) A director of a company must avoid a situation in which he has, or can have, a direct or indirect interest that conflicts, or possibly may conflict, with the interests of the company.

(2) This applies in particular to the exploitation of any property, information or opportunity (and it is immaterial whether the company could take advantage of the property, information or opportunity).

(3) This duty does not apply to a conflict of interest arising in relation to a transaction or arrangement with the company.

(4) This duty is not infringed –

(a) if the situation cannot reasonably be regarded as likely to give rise to a conflict of interest; or

(b) if the matter has been authorised by the directors.

(5) Authorisation may be given by the directors –

(a) where the company is a private company and nothing in the company’s constitution invalidates such authorisation, by the matter being proposed to and authorised by the directors; or

(b) where the company is a public company and its constitution includes provision enabling the directors to authorise the matter, by the matter being proposed to and authorised by them in accordance with the constitution.

(6) The authorisation is effective only if –

(a) any requirement as to the quorum at the meeting at which the matter is considered is met without counting the director in question or any other interested director, and

(b) the matter was agreed to without their voting or would have been agreed to if their votes had not been counted.

(7) Any reference in this section to a conflict of interest includes a conflict of interest and duty and a conflict of duties.’

A director of a company is quite likely, at some point in his directorship, to find himself in a situation in which his duty to advance the interests of the company comes into conflict with his personal interest or a duty he owes to another person. An example of a situation with the potential to give rise to a conflict is where a director wishes to take up an opportunity that has been offered to but declined by the company. Other examples are where a director is on two or more boards of directors and one company is a major customer, supplier or competitor of the other.

Multiple directorships are common in the UK, especially amongst non-executive directors of large quoted companies. Consequently, the power to authorise conflict situations and thereby remove them from the statutory duty of a director to avoid a situation in which he has, or can have, a direct or indirect interest that conflicts, or possibly may conflict, with the interests of the company is of great practical importance.

Director authorisation

Section 175 permits the board of directors to authorise conflicts of interest. This is in contrast to the pre-2006 Act law which reserved the power to authorise conflicts of interest to the shareholders unless the articles provided otherwise (which they regularly did). Note that the power of the shareholders to authorise conflicts has been preserved by s 180(4)(a). The conditions for availability of s 175(5) authorisation are different for private and public companies.

Private company director authorisation of conflicts

The s 175(5) power of directors to authorise conflicts is automatic for private companies registered on or after 1 October 2008, provided nothing in its articles (constitution) invalidates such authorisation (s 175(5)(a)). Important transitional provisions state that director authorisation will only apply to private companies incorporated before that date where the shareholders have resolved (before, on or after 1 October 2008) that authorisation may be given in accordance with s 175(5) (see para 47(3) of Sched 4 to the Companies Act 2006 Fifth Commencement Order (SI 2007/3495)).

Public company director authorisation of conflicts

The board of a public company is only permitted to authorise conflicts pursuant to s 175(5) if the articles (constitution) include a provision enabling the directors to do so.

Entry into force of s 175 was delayed until 1 October 2008 to enable private companies to consider the matter and, if they so required, amend their articles to provide that director authorisation pursuant to s 175(5) was not permitted. Public companies, on the other hand, were to consider providing in their articles that directors may authorise conflicts pursuant to s 175(5).

Conditions for effective director authorisation

Section 175(6) governs the conditions of effective director authorisation. Any requirement as to the quorum at the meeting at which the matter is considered must be met without counting the director in question or any other interested director, and the matter must be agreed to without their voting or it must be the case that it would have been agreed to if their votes had not been counted. Note also that authorisation must be obtained in advance of acting in what would otherwise be a conflict of interest matter. When deciding whether or not to authorise a conflict, a director must, of course, act in accordance with all of the duties he owes to the company. He will be in breach of s 172, for example, if he votes to authorise a conflict if he does not consider, in good faith, that the authorisation would be most likely to promote the success of the company.

What is a conflict of interest?

Guidance in the 2006 Act

The 2006 Act contains no definition of conflict of interest. When, then, will a conflict of interest exist for the purposes of the s 175 duty?

Section 175(7) spells out that a conflict of interest includes a conflict of interest and duty and a conflict of duties.

Section 175(7) spells out that a conflict of interest includes a conflict of interest and duty and a conflict of duties.

Section 175(3) provides that a conflict arising in relation to a transaction or arrangement with the company is not a conflict covered by s 175 (regulation of these transactions and the scope of s 175(3) are considered in section 12.3, see in particular the example at the end of 12.3.2).

Section 175(3) provides that a conflict arising in relation to a transaction or arrangement with the company is not a conflict covered by s 175 (regulation of these transactions and the scope of s 175(3) are considered in section 12.3, see in particular the example at the end of 12.3.2).

Section 175(1) refers to the duty to avoid a situation in which the director has, or can have, a direct or indirect interest that conflicts, or possibly may conflict, with the interests of the company, yet s 175(4) states that the duty does not apply if the situation cannot reasonably be regarded as likely to give rise to a conflict of interest.

Section 175(1) refers to the duty to avoid a situation in which the director has, or can have, a direct or indirect interest that conflicts, or possibly may conflict, with the interests of the company, yet s 175(4) states that the duty does not apply if the situation cannot reasonably be regarded as likely to give rise to a conflict of interest.

Section 175(2) reinforces that the duty applies in particular to the exploitation of any property, information or opportunity.

Section 175(2) reinforces that the duty applies in particular to the exploitation of any property, information or opportunity.

Section 175(2) goes on to state that it is immaterial whether the company could take advantage of the property, information or opportunity, yet again, it is difficult to reconcile this with the duty not applying if the situation cannot reasonably be regarded as likely to give rise to a conflict of interest (s 175(4)).

Section 175(2) goes on to state that it is immaterial whether the company could take advantage of the property, information or opportunity, yet again, it is difficult to reconcile this with the duty not applying if the situation cannot reasonably be regarded as likely to give rise to a conflict of interest (s 175(4)).

Beyond the clues in s 175 as to when a conflict of interest will exist, it is instructive to examine pre-2006 Act conflict of interest cases to have a sense of when a director will be found to have a conflict of interest for the purposes of s 175. Many cases have concerned directors exploiting corporate opportunities themselves after they have left the company, which raises the question when do directors who leave a company cease to be subject to the duty. In other cases, the company has not been in a position to exploit the opportunity itself, or has decided not to. Each of these situations is considered in turn in the following paragraphs.

Corporate opportunities and directors who leave or are in the process of leaving the company

Section 170(2) specifically provides that a person who ceases to be a director continues to be subject to the duty in s 175, ‘as regards the exploitation of any property, information or opportunity of which he became aware at a time when he was a director’. What is not always clear is whether such exploitation is, as a matter of fact, a conflict of interest. Two types of cases dealing with directors who leave companies and take up opportunities the companies consider they should not have exploited for their own benefit are where a director leaves deliberately in order to acquire an opportunity previously sought by and for the company, and where a director is forced out of a company. In relation to the first of these scenarios, the law is strictly applied.

| Canadian Aero Service Ltd v O’Mally (1973) 40 DLR (3d) 371 Two directors, the president and vice president of the company, tried to obtain a contract on behalf of the company and were active participants in the negotiations. They then resigned, formed a new company and acquired the contract for the new company. Held: The directors were liable to account to their former company for the profits made. This was a diversion of a maturing business opportunity that the company was actively pursuing. Laskin J stated that even after his resignation a director is precluded from exploiting the opportunity ‘where the resignation may fairly be said to have been prompted or influenced by a wish to acquire for himself the opportunity sought by the company, or where it was his position with the company rather than a fresh initiative that led him to the opportunity which he later acquired’. | |

In contrast, there may be no conflict where a director performs services for a customer of the company in competition with the company, even whilst he is a director, if he is in the process of being forced out of the company. Starting from the principle illustrated in London and Mashonaland Exploration Co Ltd v New Mashonaland Exploration Co Ltd [1891] WN 165, that there is no completely rigid rule that a director may not be involved in the business of a company which is in competition with another company of which he is a director, the Court of Appeal in Plus Group Ltd v Pyke [2002] 2 BCLC 201 (CA) considered it possible for a director’s duty to be ‘reduced to vanishing point’ on the facts because he had been squeezed out of any management role in the company. In those circumstances, a director who set up a new company to compete with the company and performed services for a major client of the company, was held not to be in breach of duty.

In Foster Bryant Surveying Ltd v Bryant & Savernake Property Consultants Ltd [2007] 2 BCLC 239 (CA), the Court of Appeal explored the duty of a director between resigning (he was effectively forced out of a company) and his resignation taking effect in the context of a customer of the company wishing to continue to secure the services of the director. Rix LJ’s judgment is worth reading for its clear review of the ‘corporate opportunity’ authorities. He focused on the need for a link between the resignation and the obtaining of the business by the director, i.e. the resignation must be part of a dishonest plan. He stated that the standards of loyalty, good faith and the no-conflict rule should be tested in each case by many factors, i.e. a fact-intensive investigation was required to determine liability for breach. Amongst the factors to be considered in that enquiry are:

position or office held;

position or office held;

nature of the corporate opportunity;

nature of the corporate opportunity;

its ripeness;

its ripeness;

its specificness;

its specificness;

the director’s or managerial officer’s relation to it;

the director’s or managerial officer’s relation to it;

the amount of knowledge possessed;

the amount of knowledge possessed;

the circumstances in which it was obtained;

the circumstances in which it was obtained;

whether it was special or, indeed, even private;

whether it was special or, indeed, even private;

the factor of time in the continuation of fiduciary duty where the alleged breach occurs after termination of the relationship with the company;

the factor of time in the continuation of fiduciary duty where the alleged breach occurs after termination of the relationship with the company;

the circumstances under which the relationship was terminated, that is whether by retirement or resignation or discharge.

the circumstances under which the relationship was terminated, that is whether by retirement or resignation or discharge.

Companies that cannot or do not wish to pursue a corporate opportunity

The strict principle that a fiduciary may not benefit from a corporate opportunity even where the company could not have benefited from the opportunity itself, infamously applied to a solicitor and trustee in Boardman v Phipps [1967] 2 AC 46, has been applied to company directors in what was the leading case on conflict of interest before the 2006 Act, Regal (Hastings) Ltd v Gulliver [1967] 2 AC 134.

CASE EXAMPLE | ||

| Regal (Hastings) Ltd v Gulliver [1967] 2 AC 134 The board of directors of Regal (Hastings) Ltd, acting together and honestly, bought shares in a subsidiary of the company set up to facilitate the sale of the company’s business. Regal (Hastings) Ltd had been given the option to acquire the shares but lacked the finances to do so. On the subsequent sale of the company and the partly owned subsidiary, the directors made profits on their shares in the subsidiary company. The new owners of the company brought proceedings against the directors to recover those profits. Held: The directors had not disclosed their intention to acquire the shares to the shareholders and obtained the approval of the shareholders to their action. Accordingly, the directors were in breach of the duty not to make a secret profit. | |

The reference in s 175 to it being immaterial whether the company could take advantage of the property, information or opportunity alleged to have been exploited by the director can be traced back to this case. Yet later cases, such as Foster Bryant, showed the willingness of the courts to take a ‘common sense and merits based approach … which reflects the equitable principles at the root of these issues’ (per Rix LJ). As we have seen, this more flexible approach is also reflected in s 175 insofar as s 175(4)(a) states that the duty is not infringed if the situation ‘cannot reasonably be regarded as likely to give rise to a conflict of interest’. It is clear that Regal (Hastings) Ltd v Gulliver would be decided in the same way were it to come to court today and s 175 applied to determine whether or not the directors were liable to account for the profits they made based on a breach of the duty not to put themselves in a position in which their personal interest and the interests of the company conflicted.

Further strict applications of the rule occurred in Philip Towers v Premier Waste Management Ltd [2011] EWCA Civ 923 (CA) and Bhullar v Bhullar [2003] 2 BCLC 241 (CA). In Bhullar two directors of a small company, which was not currently developing any further land, bought land in which the company would otherwise have been interested, for development by themselves personally. Although he approved the quotation below from the dissenting judgment of Lord Upjohn in the leading case of Boardman v Phipps [1967] 2 AC 46 (HL), Jonathan Parker LJ went on to find the directors liable for breach of duty, as ‘reasonable men looking at the facts would think there was a real sensible possibility of conflict’.

| ‘The phrase “possibly may conflict” requires consideration. In my view it means that the reasonable man looking at the relevant facts and circumstances of the particular case would think that there was a real sensible possibility of conflict, not that you could imagine some situation arising which might, in some conceivable possibility in events not contemplated as real sens! ible possibilities by any reasonable person, result in a conflict.’ | |

That it is no defence to a claim for breach of s 175 that the company would not have been able to exploit the misappropriated opportunity itself was recently confirmed in Penny-feathers Ltd v Pennyfeathers Property Co Ltd [2013] EWHC 3530 (Ch), a case involving the development of a large plot of land in the Isle of Wight.

Shareholder consent and acquiescence to pursuit of corporate opportunities by directors

In a number of cases the court has been called upon to consider the defence of shareholder consent to directors pursuing corporate opportunities. The authorities were reviewed and the defence was successful in the recent case of Sharma v Sharma [2013] EWCA Civ 1287 in which Jackson LJ (with whom the other members of the Court of Appeal agreed) summarised the principles as follows:

JUDGMENT | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||

12.2.2 Duty not to accept benefits from third parties

SECTION

‘176 Duty not to accept benefits from third parties

(1) A director of a company must not accept a benefit from a third party conferred by reason of –

(a) his being a director, or

(b) his doing (or not doing) anything as director.

(2) A ‘third party’ means a person other than the company, an associated body corporate or a person acting on behalf of the company or an associated body corporate.’