Facing wars, confronting threats: the UN Security Council in action

Chapter 3

Facing wars, confronting threats: the UN Security Council in action

If the purpose of the UN was to save mankind from the destruction that had overshadowed the history of the first half of the twentieth century, measuring its success depends on one’s perspective. On the one hand, it could be argued that since no World War III has erupted, the founders had created a successful organization. On the other hand, not a day has gone by since 1945 without a deathly military conflict somewhere on the globe. Many such conflicts have transpired and continued with the full knowledge of the United Nations Security Council (UNSC). In short, the UN may have played a role in saving mankind from the devastation of global war, but it has not come close to eliminating the scourge of war from our planet.

Nor is it clear whether the absence of global military confrontation has had much to do with the UN and its executive body, the Security Council. It can be argued that the existence and proliferation of nuclear weapons acted as a deterrent against a direct military confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union. The potential consequences of such a war—a rapid annihilation of one’s own country—removed the incentive to go to war far more effectively than any deliberations at the UN. But the United States and the USSR were more than happy to intervene in military conflicts around the globe that did not seem likely to escalate into a direct superpower confrontation. After the Cold War new antagonisms emerged, most evidently within the context of the United States’ call for regime change in Iraq in 2002–03.

This does not mean that the Security Council was or is irrelevant. It simply underlines the fact that at its very founding, this central organ of the UN could be effective only when the so-called P-5 were in agreement. In fact, the UNSC has on numerous occasions exercised an important role as a global troubleshooter. Taking into account the dependence of the UNSC on the unanimity of its five permanent members—and hence on the national interests of China, France, Great Britain, Russia (formerly the Soviet Union), and the United States—it has actually been remarkably successful and active. Ideally, the Security Council’s role should not be purely reactive. It should also be able to address potential threats and prevent them from materializing. The relationship between UNSC and the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), sometimes referred to as the UN’s “nuclear watchdog,” is a good example of the potential that the UN has for making a positive impact on international security in the twenty-first century. There is probably no other issue besides the possibility of a nuclear holocaust to bring peoples and countries together. Yet the attempt to safeguard against the proliferation of such weapons has been a half-hearted success at best. Once again, national interests have clashed with global security concerns to produce a series of imperfect compromises and temporary solutions.

Political constraints: the veto conundrum

In theory, the Security Council has few limits to its power. Its remit is broad; its resolutions are binding on all members of the UN. In short, if the UNSC decided something—to impose sanctions against a country or to enforce a ceasefire in a conflict area—the order would have to be implemented. One could not, in other words, ignore the collective will of the P-5 that effectively determines the decisions of the UNSC. But finding such collective will has often been an elusive quest. The question of national sovereignty is at the top of the list, and it is something that those who are “more equal” than others—that is, the P-5—hold particularly dear. And since they have the right to veto decisions, they are likely to do so should a proposed resolution be against their national interest.

Veto power (“Great Power unanimity”)

Each UN Security Council member has one vote. Decisions on procedural matters (for example, whether an issue is to be discussed by the UNSC at all) require the support of at least nine of the fifteen members. Decisions on substantive matters (for example, a decision calling for direct measures to settle an international dispute, or to employ sanctions) also require nine votes, but these must include the votes of all five permanent members. This is the rule of “Great Power unanimity,” often referred to as the “veto” power.

In theory the nonpermanent members of the UNSC also hold a collective veto power: if at least eight of them vote collectively against a resolution (whether procedural or substantive) they can block a resolution even if all the permanent members vote for it. This so-called sixth veto has existed only since 1965, when the number of nonpermanent members was increased from six to ten. Although all P-5 members have used their veto power repeatedly, the sixth veto has yet to be employed.

The P-5’s right of veto has complicated the UNSC’s work more than any other issue. Indeed, the fact that five nations—out of a total of 193—have a privileged position seems absurd. If the People’s Republic of China (and, more absurdly, between 1949 and 1971 the small island of Taiwan, known as the Republic of China), France, Great Britain, Russia, and the United States can agree on a course, then the UN can act. If they do not—or if only one of them decides that a certain resolution is objectionable—then the UNSC is effectively paralyzed.

Thus, the use of the veto can actually prevent the UN from enforcing measures to end a war. This was the case, for example, in December 1971, when the Soviet Union vetoed a UN resolution calling for a ceasefire in a war between India and Pakistan. By doing so the Soviets were helping India to continue its military advances against Pakistan, a firm American ally in the Cold War. Truth be told, Pakistan had won few friends because of its repression of an independence movement in what was soon to become the independent nation of Bangladesh (but was until 1971 formally known as East Pakistan). Yet the Pakistani government was perfectly within its rights when it complained that the international community was failing to enforce a peaceful resolution and, in effect, left the outmaneuvered Pakistanis no alternative but to surrender (which they did on December 16, 1971). Witnessing his country’s hardships from New York, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, the foreign minister of Pakistan, erupted in front of a UN Security Council meeting: “Let’s build a monument for the veto. Let’s build a monument for impotence and incapacity.”1

Chart 3.1 Use of the Veto.

During the Cold War the USSR was the most frequent user of the veto. After first using it in 1970, however, the United States has taken over this role. Yet, as the chart shows, the P-5 have almost ceased exercising this privilege since the end of the Cold War.

To be sure, the General Assembly has often issued resolutions despite a P-5 veto. But such resolutions simply do not carry the authority necessary to outweigh a stubborn permanent UNSC member. Nor does the fact that the nonpermanent members of the UNSC hold a theoretical “sixth veto” since the expansion of Security Council membership in the 1960s make the body either more effective or less driven by great power prerogatives.

The UNSC, for better or worse, was and remains an arena of power and realpolitik. And despite attempts to reform it, the body remains, after seven decades, more or less the way it was at the founding: empowered in theory but incapacitated in practice.

Operational constraints: the Military Staff Committee

In order to prevent wars and stop the ones that did erupt, the UN needed a military capacity. How else could the organization throw its weight around but by dispatching troops to a troubled region? How else could the UN force warring parties—unwilling to yield to diplomatic or economic pressure—to cease fighting but by displaying superior military prowess?

The UN Charter addressed these questions. It set up the Military Staff Committee (MSC) as a subsidiary body of the Security Council and charged it with the planning of UN military operations. The MSC was further mandated to assist the Security Council in arms regulation (including, implicitly, the regulation of nuclear arms). Moreover, the MSC was to provide the command staff for a set of air force contingents provided by the P-5. The contingents themselves were to be scattered on UN bases around the globe so that the Security Council could call upon them as needed.

The problem with this plan soon became evident. None of the P-5 saw an independent military force serving their interests. The mistrust and tensions of the early Cold War—including the creation of such military alliances as NATO and the Warsaw Pact—meant that none of the P-5 provided the required forces. Already in July 1948—following two years of negotiations—the MSC reported to the Security Council that it was unable to fulfill its mandate.

Consequently, although it was the only subsidiary body of the Security Council mentioned in the charter, the MSC became “dormant” (or irrelevant, in non-UN language). To be sure, there was a brief revival of interest in the MSC in 1990 when it played a role in coordinating naval operations during the Gulf War. In the end, however, the UN has shifted toward subcontracting the use of force to regional bodies such as NATO (for example in Kosovo) or the African Union (in Darfur) rather than creating a structured and effective military capacity of its own.

After seventy years the MSC still exists as an advisory body that plays a role in the planning and conduct of UN peacekeeping operations. It consists of army, naval, and air force representatives of the P-5. This group meets every two weeks at the UN headquarters in New York. Other UN members are included in meetings regarding peacekeeping operations in which their country’s forces are deployed. But the practical significance of the MSC remains, as it always has been, extremely limited.

Political constraints: Security Council and the Cold War

The record of the UNSC is checkered. To be sure, it deliberated on virtually all international conflicts during the Cold War, such as the Arab-Israeli wars, Korea, Suez, Congo, and Berlin. In all those cases, however, it was contingency—the specific interests of the P-5 (and especially the United States and the Soviet Union)—rather than the principles of the UN Charter that ultimately decided the outcome.

While the veto power of the P-5 extends to a number of areas—including the choice of the UN Secretary-General or the admission of new members to the UN—what truly counts is the way in which the P-5’s privileged position has affected the UN’s ability in matters related to war and peace. Of course, the line even here has often been blurred and the actual measures taken—and resolutions passed or not passed—depended ultimately how and if the interests of the P-5 were influenced by the conflict in question.

For example, the first Soviet use of the veto, in February 1946, was over a resolution regarding the withdrawal of French forces from Syria and Lebanon. The Soviet UN ambassador argued that the regimes slated to take over these countries were essentially French puppet governments. Later in the same year, the UNSC refused to discuss a Siamese complaint about French military activities on its border with Indochina and could not come to an agreement over an investigation regarding the communist-royalist civil war in Greece.

The major division within the Security Council’s P-5 was, though, straightforward and reflected the emergence of the Cold War. On most issues where the veto was used, the Soviet Union stood on one side, the other four members on the other. This, effectively, guaranteed a deadlock on most issues, including such hot concerns as the division of Berlin. In June 1948, the USSR—which occupied East Germany, including all areas surrounding Berlin, after the war—cut off all land connections and supply routes to West Berlin. The American, British, and French forces occupying that part of the German capital (as well as the Germans who lived there) were, essentially, hostages. To overcome the blockade, the United States commenced a massive airlift of food and other supplies. It lasted almost a year.

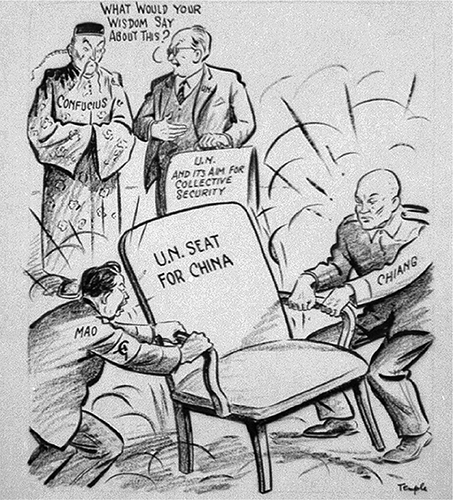

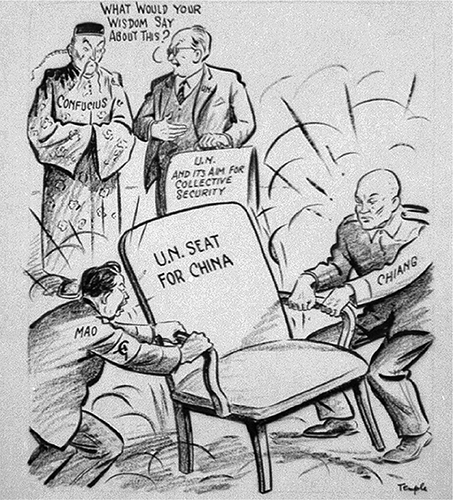

6. A 1953 cartoon illustrates the struggle between Mao Zedong, chairman of the Communist Party in Communist China, and Chiang Kai-Shek, president of Nationalist China, for the “China seat” in the UN.