Reform and challenges: the future of the United Nations

Chapter 7

Reform and challenges: the future of the United Nations

“If the United Nations is to survive, those who represent it must bolster it; those who advocate it must submit to it; and those who believe in it must fight for it.”1 Norman Cousins, a prominent journalist and peace advocate, uttered these words in 1956. They continue to resonate today, for the UN is hardly a perfect institution. It is structurally flawed and operationally cumbersome. It often lacks the means of implementation even as it may serve as the source of excellent ideas. Its different programs often duplicate work that might be better done by one centralized agency. In short, the UN is in need of reform and support if it is to have a meaningful future.

These issues—reforming the system and obtaining wide international support—are neither new nor separate. Ever since the early 1990s, there has been talk about the need to reform the UN Security Council in order to make it more democratic and representative. Nor was it an accident that the last decade of the twentieth century saw a massive litany of initiatives—or “agendas”—that addressed the key functions of the UN system: peace, democracy (and human rights), and development. In the twenty-first century hardly a day has gone by without complaints and arguments over the way development aid is administered, human rights are not effectively promoted, peace operations are not producing sustained results, and a few countries, most notably the United States, are treating the UN as a mere tool of their policy that can be used, abused, or ignored as those in power in Washington see fit.

And yet, very few would seriously suggest scrapping the UN altogether. It remains indispensable but in need of reform. But how can this impossible hybrid that represents the widely different interests of virtually all inhabitants of this globe be improved? What can be done to enhance the UN’s effectiveness in safeguarding international security and helping war-torn societies get back on their feet? In what way could the UN’s development policies be changed to improve the chances of success in the long struggle against poverty and all its undesirable side effects? How can the UN safeguard both human security and human rights in a more assertive manner?

Need for reform: the Security Council

How could the Security Council be made more effective as an instrument of solving international disputes? How could it be made more representative of the global community? The question of reforming the UNSC tends to focus on two intertwined issues: veto and membership.

Proposals abound. In the early 1990s a number of countries floated around the idea of abandoning the veto and doubling the size of the Security Council membership. In this way, countries like Germany, Japan, India, and Brazil (all strong candidates for membership) argued, UNSC would become more reflective of the changed global constellation of power.

Two obvious problems, still hindering serious reform two decades later, became evident. First, any attempt to remove the veto was bound to be vetoed. There is no realistic provision within the UN Charter that would allow the removal of the veto right without the P-5’s unanimous consent. But why would China, France, Great Britain, Russia, or the United States give up this obvious trump card? Moreover, the veto had been conceived in order to keep the five countries, especially the United States, in the organization by enabling them to block decisions they would have found against their national interests.

Second, the addition of new permanent members—with or without the right of veto—has run into many objections from countries that either feel they should be in serious contention for such a privileged position and/or have a strained relationship with a potential candidate country. Many Europeans, for example, object to Germany’s membership; Argentina sees little merit in having Brazil elevated to new heights; and Pakistan looks at India’s council bid with distinct animosity.

This, basically, means that the Security Council is destined to remain undemocratic and virtually unchanged. While its composition may be tinkered with, there is not going to be a dramatic overhaul; an addition of a few new members is possible, but is the creation of permanent seats for certain countries (such as those just mentioned) possible? The P-5 will not give up their powers voluntarily.

Yet, one should not despair. Reforming the veto power of permanent Security Council members—or adding new members to the UNSC—is a much debated and potentially important possibility. But how necessary is it? It alone provides no miracle cure. UNSC resolutions are almost always compromises, vetoes have been used fairly sparingly over the past six decades, in part because the need to veto is negotiated away, or a mere threat of a veto may lead to the proposal being withdrawn.

In the end, reforming how the UNSC works is hardly the only way of improving the UN’s overall effectiveness. In fact, it addresses only a small part of the issues plaguing the organization at the moment and hardly touches upon the “real” issues of the day. For the international security challenges faced by the UN today are vastly different than those in earlier decades. As reflected in the Secretary-General’s High Panel Report on Global Security Challenges, the world of the twenty-first century is confronted by such concerns as nuclear terrorism, state collapse, and the rapid spread of infectious disease. Viewed in this context, debates over the size of the Security Council and the ins and outs of the veto right are hardly the most pressing issues in the field of international security.

High-Level panel on threats, challenges, and change

In September 2003, noting that “the events of the past year have exposed deep divisions among members of the United Nations on fundamental questions of policy and principle,” UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan created the panel to ensure that the United Nations remains capable of fulfilling its primary purpose as enshrined in article 1 of the charter—“to take effective collective measures for the prevention and removal of threats to the peace.”

The panel, consisting of former high-level government officials from around the globe, delivered its report in 2004. It identified six clusters of global threats:

The panel highlighted the fact that the UN was in a position to deal with all such threats, but that it needs to:

Revitalize the General Assembly and the Economic and Social Council

Restore credibility to the Commission on Human Rights

Strengthen the role of the Secretary General in questions of peace and security

Increase the credibility and effectiveness of the Security Council—the panel emphasized the need for “making its composition better reflect today’s realities”

Create a Peacebuilding Commission

Some of these suggestions have since been carried out, most notably the creation of the Peacebuilding Commission in 2006.

Need for reform: peace operations

The drive toward reforming the UN’s peace operations gathered force in the 1990s. A number of questions have been repeatedly raised. How to make most of a limited number of troops in difficult situations? How to prevent possible abuses of power—in the form of sexual exploitation and human trafficking—by the peacekeepers themselves? How to make sure that a peace operation does not interfere in a country’s democratic process and thus create new problems? How to do all this while preventing a repeat of the tragic events in Bosnia, Rwanda, and Somalia in the 1990s?

These and other questions were addressed in the 2000 Brahimi Report on Peacekeeping. The report, not unexpectedly, pointed out the obvious lack of resources that hampered many UN peace operations, emphasized the need for clear and realistic mandates, and heralded the insufficient general strategic planning of operations. But it also, and perhaps most significantly, flagged the need to develop “a rapid deployment capacity” for UN peacekeepers. The report itself provided the backdrop for the creation of the UN Peacebuilding Commission in 2006.

Despite the establishment of this commission, progress and reform along the lines of the Brahimi Report remains limited fifteen years after its initial delivery. To be sure, there are more peacekeepers in more places funded by slightly more money. But UN peace operations rarely benefit from an integrated support network. Equally important, they lack resources and depend, most of the time, on the ability of the Secretary-General to raise money for a specific operation.

Moreover, as the case of Darfur has yet again shown, the UN cannot simply impose a peacekeeping force on an unwilling host government. Instead, in order to compensate for the lack of political muscle and manpower, the UN has been forced to “outsource” some of its peacekeeping to such regional organizations as the African Union (which represented the bulk of peacekeepers stationed in Sudan after 2007). The results, as far as Darfur can stand as a case study, are hardly comforting: between 2003 and 2007 an estimated 400,000 people were killed while at least 2 million refugees fled Darfur. Talk of genocide and comparisons to Rwanda in 1993–94 were rampant.

Whether such tragedies as Darfur could have been avoided with a more intrusive and aggressive UN policy is difficult to ascertain. Without the support of its member states, and particularly the P-5 of the Security Council, no operational capability would have been meaningful. Nor does the Darfur experience of outsourcing peacekeeping to regional organizations mean that such a practice cannot be successful; NATO’s role in Bosnia seems to provide the exact opposite lesson.

In the end, when contemplating the lessons of past peacekeeping and how to make future operations more effective, one comes back to a key point in the Brahimi Report: the need for a rapid deployment capacity. How else but with an ability to send peacekeepers to different corners of the globe at short notice can the UN respond to a sudden crisis? Without such capacity it will always be rendered a second-class outfit called upon to police difficult situations or clean up the mess left by “serious” fighting.

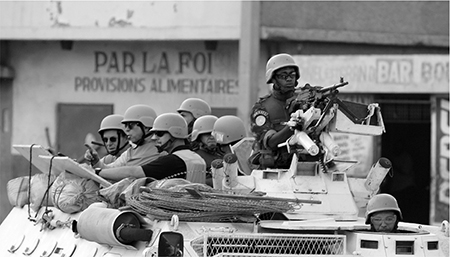

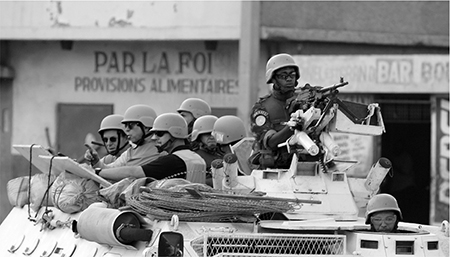

12. Jean-Marie Guéhenno, Under-Secretary-General for Peacekeeping Operations, and Juan Gabriel Valdés, special representative of the Secretary-General and head of the United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti, accompany a Brazilian patrol in Bel-Air, a hillside slum in Port-au-Prince ravaged by armed bandits in 2005.