Conventions Relating to Pollution Incident Preparedness, Response, and Cooperation (Gabino Gonzalez and Frédéric Hébert)

CONVENTIONS RELATING TO POLLUTION INCIDENT PREPAREDNESS, RESPONSE, AND COOPERATION

Gabino Gonzalez and Frédéric Hébert

Preface

This chapter has been prepared by the Regional Marine Pollution Emergency Response Centre for the Mediterranean Sea (REMPEC) with a view to providing an updated worldwide outlook of the conventions relating to pollution incident preparedness, response and co-operation and the related institutional arrangements. The information set out in this document has been reviewed by the majority of the international and regional organizations concerned, however, some data validation has not been received prior to its publication.

REMPEC is grateful to the International Maritime Organization (IMO), the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and its Regional Seas Programme Coordinating Office, the Caribbean Regional Co-ordinating Unit (CAR/RCU), the Regional Marine Pollution Emergency, Information and Training Centre (REMPEITC-Caribe), the East Asian Seas Regional Coordinating Unit, the Eastern African Regional Coordinating Unit (EAF/RCU), the Western Indian Ocean Marine Pollution Regional Coordination Centre), the Marine Environmental, the Northwest Pacific Action Plan (NOWPAP) Regional Coordinating Unit and the Marine Environmental Emergency Preparedness and Response Regional Activity Centre (MERRAC), the Regional Organization for the Protection of the Marine Environment (ROPME) Sea Area, the Marine Emergency Mutual Aid Centre (MEMAC), the Regional Organization for the Conservation of the Environment of the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden, the Marine Emergency Mutual Aid Centre (EMARSGA), the Permanent Commission for the South Pacific (CPPS), the Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme (SPREP), the Pacific Regional Environment Programme South Asia Co-operative Environment Programme (SACEP), the Central American Commission on Maritime Transport (COCATRAM), the Artic Council Emergency Prevention, Preparedness and Response Working Group (EPPR), the Secretariat of the Antarctic Treaty, the Secretariat of Helsinki Commission (HELCOM), the Secretariat of the Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the Caspian Sea (Teheran Convention), the Secretariat of OSPAR Commission, the Global oil and gas industry association for environmental and social issues (IPIECA), the Global Initiative for West and Central Africa (GI-WACAF) and the International Tanker Owner Pollution Federation (ITOPF) for their contributions in the preparation of this review.

7.1 Introduction

In March 1967, the tanker Torrey Canyon ran aground off the coast of Cornwall in the southwest of England, spilling some 121,000 tonnes of oil into the sea. It was the biggest marine pollution disaster in history at the time. Perhaps for the first time, the general public was made aware of the threat the marine transport of oil and other products poses to the marine environment.

Since the Torrey Canyon spill, the spate of accidents that have occurred shows that the threat from accidental marine pollution remains (Amoco Cadiz, 1978, off Brittany, France; Kark V, 1989, off the Atlantic coast of Morocco; Exxon Valdez, 1989, Prince William Sound, Alaska, USA; Haven, 1991, Genoa, Italy; Braer, 1993, Shetland Islands, UK; Sea Empress, 1996, Milford Haven, Wales, UK; Nakhodka, 1997, off Honshu Island, Japan; Erika, 1999, off Brittany, France; Prestige, 2002, off Galicia, Spain; and Hebei Spirit, 2007, south of Seoul, South Korea).

The International Maritime Organization (IMO) is the United Nations (UN) specialized agency with responsibility for the safety and security of shipping and the prevention of marine pollution by ships. The IMO has for decades established international conventions and protocols focusing on the governance of the maritime sector, including specific instruments relating to pollution incident preparedness, response and cooperation such as the International Convention on Oil Pollution, Preparedness, Response and Co-operation (OPRC Convention). On the other hand, the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), very active at regional level through the Regional Seas Programmes, was established to manage global environmental challenges, including, inter alia, marine environmental pollution. Within the framework of the Regional Seas Programmes, regional legal instruments concerning pollution incident preparedness, response and cooperation have been adopted, taking into account regional specificities.

This chapter sets out the timeline and evolution of the international and regional regulatory regime governing marine environment protection and provides information on the landmark conventions that have, over time, served to first establish and then further strengthen and improve the protection of the marine environment from the adverse effects of shipping.

An analysis of the content of these instruments and their geographical coverage identifies areas requiring further development. It also highlights the complementarity of international (OPRC Convention) and regional frameworks (eg Regional Seas Programmes) and the importance of common efforts, approaches, and initiatives engaged by their respective governing bodies, in close cooperation with other stakeholders.

Since 1969, several mechanisms have been established with a view to assisting governments around the globe. This chapter presents how international and regional legal instruments are implemented, taking into account regional specificities, and provides an outlook of inter-governmental coordination bodies, programmes, and initiatives involving other non-governmental stakeholders, including the oil and shipping industry, that support governments in meeting the requirements established under international and regional legal instruments.

7.2 International Legal Framework Overview

7.2.1Background

It has always been recognized that the best way of improving safety at sea is by developing international regulations that are followed by all shipping nations and from the mid-19th century onwards a number of such treaties were adopted. Several countries proposed that a permanent international body should be established to promote maritime safety more effectively, but it was not until the establishment of the United Nations itself that these hopes were realized. In 1948 an international conference in Geneva adopted a convention formally establishing the International Maritime Organization (IMO) (originally named Inter-Governmental Maritime Consultative Organization, or IMCO, which was changed in 1982 to IMO). The IMO Convention entered into force in 1958 and the new Organization met for the first time the following year.

As the UN-specialized agency responsible for the safety and security of shipping and the protection of the marine environment from its adverse effects, headquartered in London, United Kingdom, the IMO has 169 Member States and 3 Associate Members. The IMO’s primary purpose is to develop and maintain a comprehensive regulatory framework for shipping and its remit today includes safety, environmental concerns, legal matters, technical cooperation, maritime security and the efficiency of shipping. The work of the IMO is conducted through five committees and these are supported by a number of technical subcommittees.

7.2.2 IMO Conventions

The IMO is the source of approximately sixty legal instruments that guide the regulatory development of its Member States to improve safety at sea, facilitate trade among seafaring states, and protect the marine environment.

Following its establishment, the IMO initially introduced a series of measures designed to prevent tanker accidents and to minimize their consequences. The Organization also tackled the environmental threat caused by routine operations, such as the cleaning of oil cargo tanks and the disposal of engine room wastes, which, in tonnage terms, is a bigger menace than accidental pollution.

In 1954, the first international treaty that aimed to protect the sea from pollution by oil tankers, the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution of the Sea by Oil, 1954 (OILPOL), was adopted, with the IMO taking over responsibility for it in 1959. However, it was not until 1967, when the Torrey Canyon ran aground off the coast of the United Kingdom, that the enormity and scale of the problem was fully understood, serving as a driver for change. Until then, many people had believed that the seas were big enough to cope with any pollution caused by human activity.

The Torrey Canyon incident raised certain questions about the measures then in place to prevent oil pollution from ships. It also made the world aware of the inadequacies for providing compensation to those affected, following accidents at sea. For the next several years, initiatives were taken to find solutions to these questions, mainly through the IMO.

In the aftermath of the Torrey Canyon incident, which revealed the need to set up a regime for the coastal States responding to an oil pollution accident on the high sea, the IMO introduced the International Convention Relating to Intervention on the High Seas in Cases of Oil Pollution Casualties (1969 Intervention Convention), adopted on 29 November 1969 and in force since 6 May 1975.

The Convention affirms the right of a coastal State to take such measures on the high seas as may be necessary to prevent, mitigate or eliminate danger to its coastline or related interests from pollution by oil, or the threat thereof, following from a maritime casualty. The coastal State is, however, empowered to take only such action as is necessary and, after due consultations with appropriate interests, including, in particular, the flag State or States of the ship or ships involved, the owners of the ships or cargoes in question and, where circumstances permit, independent experts appointed for this purpose.

A coastal State which takes measures beyond those permitted under the Convention is liable to pay compensation for any damage caused by such measures. Provision is made for the settlement of disputes arising from the application of the Convention. The Convention applies to all seagoing vessels, except warships or other vessels owned or operated by a State and used on Government non-commercial service. The 1969 Intervention Convention also applied to casualties involving pollution by oil, but did not cover casualties involving other types of substances. In view of the increasing quantity of other substances, mainly chemical, carried by ships, some of which would, if released, cause serious hazard to the marine environment, the 1969 Brussels Conference recognized the need to extend the Convention to cover substances other than oil. The 1973 London Conference on Marine Pollution therefore adopted the Protocol relating to Intervention on the High Seas in Cases of Marine Pollution by Substances other than Oil. This extended the regime of the 1969 Intervention Convention to substances which are either listed in the Annex to the Protocol or which have characteristics substantially similar to those substances. The 1973 Protocol entered into force in 1983 and was amended in 1996 and 2002, to update the list of substances attached to it.

The Torrey Canyon was also a major driver for the establishment of the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL), the main international convention covering prevention of pollution of the marine environment by ships from operational or accidental causes, which was adopted on 2 November 1973 at the IMO. As the 1973 MARPOL Convention had not yet entered into force, the MARPOL Protocol adopted in 1978 absorbed the parent Convention. The combined instrument entered into force on 2 October 1983. In 1997, a Protocol which entered into force on 19 May 2005, was adopted to amend the Convention and a new Annex VI addressing air pollution from ships was added. MARPOL has been updated by amendments through the years. The Convention includes regulations aimed at preventing and minimizing pollution from ships—both accidental pollution and that from routine operations—and currently includes six technical Annexes. Special Areas with strict controls on operational discharges are included in most Annexes. MARPOL regulates the discharges at sea of harmful substances from ships and covers pollution of the sea by oil (Annex I), by noxious liquid substances in bulk (Annex II), by harmful substances carried by sea in packaged form (Annex III), by sewage from ships (Annex IV), and by garbage from ships (Annex V). This much amended instrument remains the flagship pollution prevention treaty amongst the array of IMO instruments.

Regulation 37 of Annex I of MARPOL with regards to oil pollution prevention, in particular, requires that oil tankers of 150 tons gross tonnage or more and all ships of 400 tons gross tonnage or more carry an approved shipboard oil pollution plan (SOPEP). The International Convention on Oil Pollution Preparedness, Response and Co-operation, 1990, further detailed below also requires such a plan for certain ships. Regulation 17 of Annex II of MARPOL makes similar stipulations for all ships of 150 tons gross tonnage and above carrying noxious liquid substances in bulk, which are required to carry on board an approved marine pollution emergency plan for noxious liquid substances. The latter should be combined with a SOPEP, since most of their contents are the same and the combined plan is more practical than two separate ones in case of an emergency. To make it clear that the plan is a combined one, it should be referred to as a shipboard marine pollution emergency plan (SMPEP).

The Torrey Canyon incident also provided a major stimulus to the establishment of a regime providing compensation to those who had suffered financially as a result of oil pollution. As a result, two treaties were adopted, in 1969 and 1971, which enabled victims of oil pollution to obtain compensation much more simply and quickly than had ever been possible before. The original Conventions were the 1969 International Convention on Civil Liability for Oil Pollution Damage (‘1969 CLC’) and the 1971 International Convention on the Establishment of an International Fund for Compensation for Oil Pollution Damage (‘1971 Fund Convention’). Both treaties were amended in 1992, and in October 2000, in the wake of the Erika accident off the coast of France, the limits of both the 1992 CLC and 1992 Fund Convention were further increased. Discussions on the establishment of a regime offering an even higher level of compensation continued after the Erika incident. The need for such a fund was confirmed by the Prestige incident that occurred in Spain. As a result, a new Protocol creating the International Supplementary Fund for Compensation for Oil Pollution Damage (‘Supplementary Fund’), was adopted in May 2003. This new ‘third tier’ Fund, which was closely modelled on the 1992 Fund, was designed to address the concerns of those States that were of the view that the enhanced 1992 CLC and Fund limits were still insufficient to meet in full all valid claims arising from a major tanker accident. The Supplementary Fund substantially increased the limits of compensation available to Parties to roughly one billion US dollars.

As MARPOL came into being in the 1970s and as the international compensation regime was established and matured, there was still little attention to the role, responsibilities and needs for cooperation in preparing for and responding to incidents of major pollution.

In the aftermath of the Torrey Canyon, the IMO urged governments to establish arrangements for dealing with oil pollution accidents. In November 1968, the IMO Assembly adopted three important interrelated resolutions:

–Resolution A.148 (ES.IV), National Arrangements for Dealing with Significant Spillages of Oil

–Resolution A.149 (ES.IV), Regional Co-operation in Dealing with Significant Spillages of Oil

–Resolution A.150 (ES.IV), Research and Exchange of Information on Methods for Disposal of Oil in Cases of Significant Spillages

The concern that pollution arising from maritime accidents should be mitigated by cooperative action between neighbouring States was again reiterated by the IMO in its November 1979 Assembly Resolution A.448 (XI), by which governments were urged first to develop or improve national contingency arrangements to the extent feasible and, secondly, to develop, as appropriate, joint contingency arrangements at a regional, subregional, or sectoral level or on a bilateral level.

The first regional agreements for cooperation in combating oil pollution in case of emergency were adopted:

–by the coastal States of the North Sea (Agreement for Cooperation in Dealing with Pollution of the North Sea by Oil and Other Harmful Substances, ie Bonn Agreement), in 1969,

–by the Mediterranean coastal States (The Protocol concerning Co-operation in Combating Pollution of the Mediterranean Sea by Oil and other Harmful Substances in Cases of Emergency to the Barcelona Convention) in 1976, and

–by Bahrain, I.R. Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, in 1978 (The Protocol concerning Regional Co-operation in Combating Pollution by Oil and Other Harmful Substances in Cases of Emergency).

These instruments prepared with the support of IMCO (IMO), preceded the International Convention on Oil Pollution, Preparedness, Response and Co-operation (OPRC) and were used as references for the drafting of this international instrument.

The 1989 Exxon Valdez incident that occurred in Alaska was an important driver for change. Within one year of its occurrence, Governments came together and the OPRC Convention was adopted in November 1990 and came into force in May 1995. This Convention provided an international framework for cooperation and mutual assistance in preparing for and responding to major oil pollution incidents and required States to plan and prepare by developing national emergency response structures in their respective countries, and by maintaining adequate capacity and resources to address oil pollution emergencies.

Specifically, the OPRC Convention includes requirements for oil pollution emergency plans for ships, offshore units, sea ports and oil handling facilities operating in State waters, and procedures for reporting oil pollution incidents when these occur. The Convention also requires the establishment of national emergency system, including the development of a national contingency plan and the designation of a competent national authority and a national operational contact points. Possibly the most important aspect of the OPRC Convention is the international cooperation dimension, which enables a Party to request international assistance from other State Parties. Through the provisions concerning regional arrangements, States are urged to develop bilateral and multilateral agreements for preparedness and response to increase national capacity in the event of major pollution incidents.

Although oil spills remain the largest threat due to the volumes transported, the risk of incidents involving chemicals or ‘hazardous and noxious substances’ (HNS) continued to increase steadily with the increasing volume of chemicals transported by sea. These substances also often represent a higher degree of hazard than petroleum products, not only to the marine environment, but also to human health. Acknowledging the growing threat from the carriage of HNS by sea, in 2000, the IMO adopted the Protocol on Preparedness, Response and Co-operation to Pollution Incidents by Hazardous and Noxious Substances, 2000 (OPRC-HNS Protocol), which applies to hazardous and noxious substances other than oil, that is, chemical substances. The OPRC-HNS Protocol, which entered into force in 2007, follows the principles and provides the same basic framework for cooperation and mutual assistance as provided by the OPRC Convention.

During this same general timeframe the International Convention on Liability and Compensation for Damage in Connection with the Carriage of Hazardous and Noxious Substances by Sea, 1996 (HNS Convention), which extended the compensation and liability framework to chemical substances, was adopted in May 1996. The Convention aims to ensure adequate, prompt, and effective compensation for damage to persons and property, costs of clean-up and reinstatement measures and economic losses caused by the maritime transport of hazardous and noxious substances (HNS), but has yet to enter into force, as of November 2015.

To overcome this challenge and some of the other issues thought to be acting as barriers to ratification of the HNS Convention, a draft Protocol was adopted in 2010 to address the practical problems that were believed to have prevented States from ratifying the Convention. In spite of the new measures introduced to facilitate and promote the ratification of the HNS Convention, as of November 2015, it has yet to meet its entry into force conditions.

The liability and compensation regime was extended once more through the introduction of the International Convention on Civil Liability for Bunker Oil Pollution Damage (Bunkers Convention), that for the first time, following its entry into force in 2008, provided compensation from spills of bunker fuel from vessels other than tankers carrying persistent oils (as represented by the CLC and Funds Conventions).

7.2.3The OPRC Convention main requirements

The OPRC Convention encompasses ten key elements which are also found in other regional instruments as further detailed in the following chapters:

–Oil pollution emergency plans (Article 3): Operators of offshore unit, authorities in charge of ports, and oil handling facilities under the jurisdiction of the Party to the Convention are required to have an oil pollution emergency plan. Such plans shall be coordinated with the national system. Ships are also required to have on board an oil pollution emergency plan in accordance with practices provided for in existing international Conventions (Regulation 37 of Annex I of MARPOL and Regulation 17 of Annex II of MARPOL requiring shipboard oil pollution plans (SOPEP)).

–Oil pollution reporting procedures (Article 4): Persons in charge of ships, offshore units, sea ports and oil handling facilities, maritime inspection vessels or aircraft, and pilots of civil aircraft are requested to report any discharge of probable discharge of oil or the presence of oil.

–Action on receiving an oil pollution report (Article 5): Upon receipt of the pollution report, immediate assessment is required. Information on the assessment and action taken shall be communicated to States whose interests are affected or likely to be affected. This information shall also be communicated directly to the IMO or through the relevant regional organization or arrangements, when the severity of such oil pollution incident so justifies.

–National and regional systems for preparedness and response (Article 6): Designation of competent authorities for oil spill preparedness and response, receipt and transmission of pollution report and for deciding to render assistance are minimum requirements of the Convention together with the establishment of a national contingency plan. In addition, this Article call for a minimum level of pre-positioned oil spill combating equipment, a programme of training and exercise, a communication plan, and a mechanism to coordinate response.

–International Co-operation in pollution response (Article 7): Subject to capabilities and availability of resources, Parties agree to cooperate and provide advisory services, technical support, and equipment upon the request of the affected country.

–Research and development (Article 8): The Convention calls for exchange of information on research and development relating to the enhancement of the state-of-the-art of oil pollution preparedness and response and encourages dialogue and the development of standards for compatible techniques and equipment.

–Technical cooperation (Article 9): Parties are required to provide support on training personnel, transfer of technology, equipment and facilities, and joint research and development programmes.

–Promotion of bilateral and multilateral cooperation in preparedness and response (Article 10): The Convention call for the establishment of bilateral and multilateral agreements for oil pollution preparedness and response.

–Institutional arrangements (Article 12): the IMO is designated to perform functions and activities related to information services, education and training, technical services and technical assistance.

–Reimbursements of cost of assistance (Annex): Guidance is provided on the reimbursement of costs of assistance in accordance with the provisions of the International Oil Pollution Compensation Funds Conventions.

7.2.4 UNCLOS

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which entered into force on 16 November 1994, provides the umbrella or common framework for the development of laws and policies for managing the world’s oceans. This Convention expressly recognizes regional cooperation on marine environmental protection and management in cases of accidental marine pollution. Article 198 requires that if a State becomes aware of cases in which the marine environment is in danger of being damaged or has been damaged by pollution, it must immediately notify other States likely to be affected by such damage and the competent international organizations. Article 199 requires that affected States shall cooperate with the competent international organizations, to the extent possible, in eliminating the effects of pollution and preventing or minimizing the damage. States are further required to jointly develop and promote contingency plans for responding to marine pollution incidents. The regional agreements developed for combating accidental marine pollution use these principles.

7.3 Regional Legal Framework Overview

7.3.1Background

By the early 1970s, the world became increasingly aware of environmental issues and as a consequence, environmental concerns were also increasing. There was also a general feeling that pollution, in particular marine pollution, should be tackled at an international level. This global concern culminated in the organization of the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment in Stockholm in 1972. Of particular relevance to the issue of international cooperation and mutual assistance to combat marine pollution, was the recommendation for governments to take early action to adopt ‘effective national measures for the control of all significant sources of marine pollution and concentrate and coordinate their actions regionally and where appropriate on a wider international basis’.

A direct result of the Stockholm Conference was the December 1972 decision of the United Nations General Assembly to establish, in 1973, the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). The Governing Council of UNEP subsequently identified ‘Oceans’ as one of its priority areas in which efforts would be focused and activities developed.

The UNEP Governing Council also endorsed a regional approach to the control of marine pollution and management of marine coastal resources and requested that regional action plans be developed. As a consequence, UNEP’s Regional Seas Programme was initiated in 1974.

The Regional Seas Programme (RSP) aims to address the accelerating degradation of the world’s oceans and coastal areas through the sustainable management and use of the marine and coastal environment, by engaging neighbouring countries in comprehensive and specific actions to protect their shared marine environment. It has accomplished this by stimulating the creation of Regional Seas programmes sound environmental management, to be coordinated and implemented by countries sharing a common body of water.

The major objective of the setting up of the RSP was to promote regional marine pollution control programmes in areas that, for geographical, ecological, or political reasons, were perceived to have common elements and interest.

The programme has steadily grown and today covers eighteen regions of the world, representing virtually all the world’s oceans and seas.

The following six of the individual RSPs are directly administered by the UNEP Division of Environmental Policy Implementation (DEPI), meaning that UNEP has been given responsibility for secretariat functions, usually through a Regional Coordinating Unit established in the region. The six RSPs are as follows:

For these RSPs, UNEP is also accountable for administering the Trust Funds and provides financial and budgetary services, as well as technical backstopping and advice, and hence is more closely and directly involved in all their projects and activities.

For the following Non-UNEP administered RSPs, other independent (regional) organizations host and/or provide the Secretariat function:

In these cases, their financial and budgetary services (Trust Funds) are managed by the programmes themselves. However, the regional activities continue to form a part of the global RSP, which in turn continues to act as a platform for cooperation and coordination.

Another category of RSP includes the following independent programmes, which have not been established under the auspices of a UNEP RSP:

These entities nevertheless participate in the global meetings of the Regional Seas (RS), share experiences and exchange policy advice and support to the developing RSPs.

The role of the global RSP is to enhance linkages, coordination, and synergies within and amongst global, regional, and partner programmes, organizations, and actors. In return, the regional programmes support the implementation of the global RS strategic directions, and report regularly on progress.

The approach taken in developing UNEP’s RSP is an action plan tailored to the needs and priorities of a region, but it can also be applied to other regions.

In most cases the Action Plan is underpinned by a legal framework, in the form of a regional Convention and associated Protocols on specific problems.

Implementation should be tailored to the regional and local specificities. The holistic approach defined by UNEP addresses all sources of pollution affecting the marine environment. Consequently, all programmes reflect a similar approach, yet each has been tailored by its own governments and institutions to suit their particular environmental challenges.

A regional Sea Programme Action Plan is built on five interdependent components:

–An environmental assessment: the state of the marine environment is monitored through a continuous coordinated pollution research programme and exchange of information to identify the problems that need priority attention in the region.

–An environmental management component, involving integrated planning of activities related to developing and managing coastal areas, aimed at controlling and preventing pollution.

–A legal component consisting of an umbrella convention embodying the general commitments of the Parties to the Convention, supported by technical and specific Protocols dealing with specific issues such as: land based pollution; preparedness and response to accidental marine pollution; dumping, and seabed activities, all of which are aimed at strengthening cooperation among States in managing the regional pollution problems identified and committing the States to an active programme.

–An institutional component, consisting of regular meetings of Contracting Parties to the regional convention, which provides an intergovernmental forum for consultation and decision-making and a regional coordinating mechanism consisting of a Regional Coordinating Unit and/or Regional Activity Centres that service specific programmes and act as a secretariat for the Action Plan or parts of it.

–A financial instrument that underpins the other four parts and ensures the financing for the implementation of the Action Plan.

The UNEP’s Regional Seas Branch based at the Nairobi Headquarters provides the oversight of the RSPs. Regional Coordination Units (RCUs), often aided by Regional Activity Centres (RACs), oversee the implementation of the programmes and aspects of the regional Action Plans, such as marine emergencies, information management, and pollution monitoring.

As the United Nations’ specialized agency concerned with the prevention of pollution from ships, the IMO plays an important contributory role in UNEP’s RSP. A strong relationship has been established between the two entities as set out in chapter IV.1.

The regions where action plans and conventions have or are being developed are set out below in Table 7.1 and are further detailed in the following sections.

Table 7.1Regional Action Plans and Conventions adopted

| Region | Convention and Action Plan | Adoption |

| The Baltic Region | Helsinki Convention | 1974 |

| HELCOM Baltic Sea Action Plan | 2007 | |

| The Mediterranean | Barcelona Convention | 1975 |

| Region | Mediterranean Action Plan | |

| The ROPME Area | Kuwait Convention | 1978 |

| Action Plan for the Protection and Development of the Marine Environment and the Coastal Areas | ||

| The West and Central | Abidjan Convention | 1981 |

| African Region | Action Plan for theWest and Central African Region | |

| The Wider Caribbean | Cartagena Convention | 1983 |

| Region | Action Plan for the Caribbean Environment Programme | |

| The East Asian Seas | No Convention | 1981 |

| Region | East Asian Seas Action Plan | |

| The South-East Pacific | Lima Convention | 1981 |

| Region | South-East Pacific Action Plan | |

| The Red Sea and Gulf of | Jeddah Convention | 1982 |

| Aden Region | Action Plan for the Conservation of the Marine Environment and Coastal Areas in the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden | |

| The South Pacific Region | Noumea Convention | 1986 |

| SPREP Action Plan | 1991 | |

| The Eastern African | Nairobi Convention | 1985 |

| Region | East African Action Plan | |

| The North-East Atlantic | OSPAR Convention | 1992 |

| Region | OSPAR Convention Action Plan | |

| The Black Sea Region | Bucharest Convention | 1992 |

| Strategic Action Plan for the Environmental Protection and Rehabilitation of the Black Sea | 1996 | |

| The Northwest Pacific | No Convention | 1994 |

| Region | Northwest Pacific Action Plan | |

| The South Asian Seas | No Convention | 1995 |

| Region | Action Plan for the South Asian Regional Seas Programme | |

| Caspian Sea Region | Tehran Convention | 2003 |

| Action Plan for the protection and sustainable development of the marine environment of the Caspian Sea | ||

| North-East Pacific Region | Antigua Convention | 2002 |

| Northeast Pacific Action Plan | ||

| South-West Atlantic Region | – | |

| Arctic Region | – |

7.3.2Regional Seas Programmes administered by UNEP

7.3.2.1 Mediterranean Sea

Following the establishment of the UNEP Regional Seas Programme in 1974, the Mediterranean became the first region to adopt a Regional Action Plan (Mediterranean Action Plan (MAP)) in 1975. This was quickly followed by the adoption of the Convention for the Protection of the Mediterranean Sea against Pollution (Barcelona Convention) in 1976, which entered into force in 1978, and a succession of seven landmark Protocols.

In 1976, a Conference of Plenipotentiaries representing sixteen Mediterranean coastal States and the European Communities adopted the Convention for the Protection of the Mediterranean Sea Against Pollution (Barcelona Convention), which aims at protecting the marine environment and coastal zones through prevention and reduction of pollution, and as far as possible, elimination of pollution, whether land or sea-based. The Barcelona Convention was adopted together with two specific Protocols:

–The 1976 Protocol for the Prevention of Pollution of the Mediterranean Sea by Dumping from Ships and Aircraft, which was amended in 1995. It became known as The Protocol for the Prevention of Pollution of the Mediterranean Sea by Dumping from Ships and Aircraft or Incineration at Sea (Dumping Protocol); and

–The 1976 Protocol concerning Co-operation in Combating Pollution of the Mediterranean Sea by Oil and other Harmful Substances in Cases of Emergency (Emergency Protocol) in force since 12 February 1978. The 1976 Protocol was replaced by the Protocol concerning Co-operation in Preventing Pollution from Ships and, in Cases of Emergency, Combating Pollution of the Mediterranean Sea (Prevention and Emergency Protocol) to include the prevention of pollution by ships, it was adopted in 2002 and entered into force on 17 March 2004.

The MAP legal framework was enriched over the years with five additional Protocols addressing specific aspects of Mediterranean environmental conservation as follows:

–The Protocol for the Protection of the Mediterranean Sea Against Pollution from Land-based Sources, adopted in 1980, and amended in 1996 and now known as The Protocol for the Protection of the Mediterranean Sea Against Pollution from Land-based Sources and Activities (LBS Protocol), in force since 11 May 2008;

–The Protocol Concerning Mediterranean Specially Protected Areas (SPA Protocol), adopted in 1982, and replaced by the Protocol concerning Specially Protected Areas and Biological Diversity in the Mediterranean (SPA and Biodiversity Protocol), adopted in 1995 and in force since 12 December 1999;

–The Protocol on the Prevention of Pollution of the Mediterranean Sea by Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and their Disposal (Hazardous Wastes Protocol), adopted in 1996 and in force since 18 January 2008;

–The Protocol for the Protection of the Mediterranean Sea Against Pollution Resulting from Exploration and Exploitation of the Continental Shelf and the Seabed and its Subsoil (Offshore Protocol), adopted in 1994, in force since 23 March 2011;

–The Protocol on Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM Protocol), adopted in 2008 and in force since 24 March 2011.

The introduction of the concept of sustainable development with the approach of the Rio Conference in 1992 led the Member States of the Barcelona Convention to draw up an Agenda 21 for the Mediterranean. This concept, adapted to the Mediterranean context, forms an integral part of the objectives of the MAP. In June 1995, the Mediterranean Action Plan, which was adopted in 1975, was replaced by the Action Plan for the Protection of the Marine Environment and the Sustainable Development of the Coastal Areas of the Mediterranean (renamed MAP Phase II). The legal instruments were updated to reflect and ensure coherence with the progress made in international environmental law, and are set forth in Table 7.2.

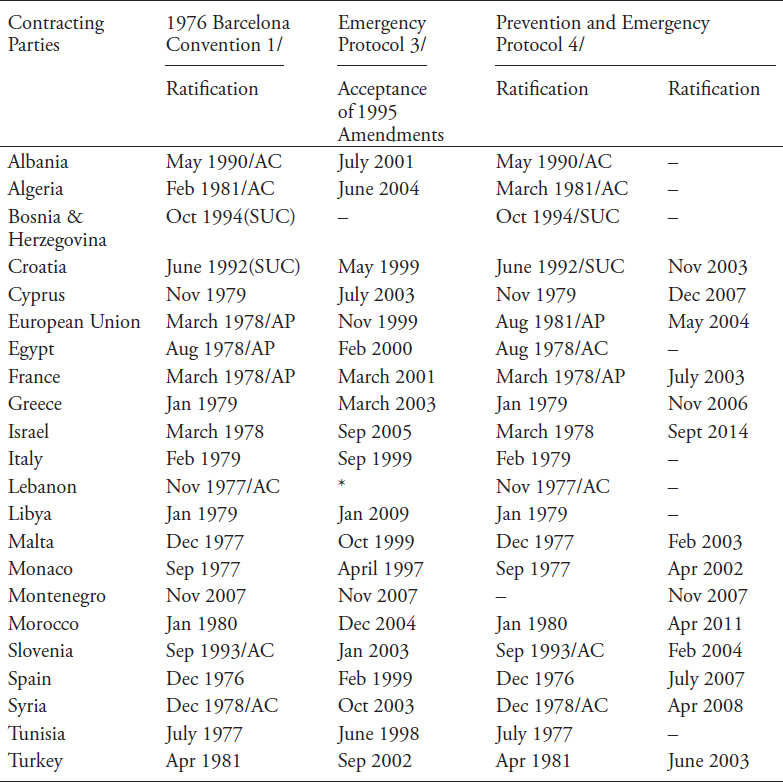

Table 7.2Ratifications of the Barcelona Convention its 1976 Emergency and 2002 Prevention and Emergency

The Contracting Parties to the Barcelona Convention consist of all twenty-one Mediterranean coastal States and the European Union. The status of ratification the Convention and its 1976 Emergency and 2002 Prevention and Emergency Protocols is set out in Table 7.2.

Accession = AC Approval = AP Succession = SUC

The Secretariat’s functions were assigned to UNEP, which subsequently established a coordinating unit in July 1982 for the Mediterranean Action Plan, hostedby Greece in Athens. Apart from its secretariat function, it is also responsible for planning, organization, information, and cooperation with intergovernmental and non-governmental organizations. In addition, Regional Activity Centres (RACs) dealing with specific components of the Mediterranean Action Plan have been set up. The Regional Marine Pollution Emergency Response Centre for the Mediterranean Sea (REMPEC), formerly the Regional Oil Combatting Centre (ROCC), was established in Malta in 1976 to support Contracting Parties in the implementation of the Emergency Protocol and, since 2002, the Prevention and Emergency Protocol.

7.3.2.2 The wider Caribbean region

The Convention for the Protection and Development of the Marine Environment in the Wider Caribbean Region, also called the Cartagena Convention, was adopted in Cartagena, Colombia, on 24 March 1983 and entered into force on 11 October 1986, for the implementation of the Action Plan for the Caribbean Environment Programme (CEP).

The Convention is supplemented by three Protocols:

–Protocol Concerning Co-operation in Combating Oil Spills in the Wider Caribbean Region which was also adopted in 1983 and entered into force on 11 October 1986.

–Protocol Concerning Specially Protected Areas and Wildlife (SPAW) in the Wider Caribbean Region which was adopted on 18 January 1990. The Protocol entered into force on 18 June 2000.

–Protocol Concerning Pollution from Land-Based Sources and Activities which was adopted on 6 October 1999 and entered into force on 13 August 2010.

Although the Contracting Parties designated the Caribbean Coordination Unit (UNEP-CAR/RCU) as Secretariat to the Cartagena Convention, Contracting Parties may use Regional Activity Centres (RACs) for the coordination and implementation of activities in support of the Cartagena Convention and its Protocols and Regional Activity Networks (RANs) for the provision of additional expertise and technical support.

The Cartagena Convention has been ratified by twenty-five Member States in the Wider Caribbean Region, as listed in Table 7.3.

The Assessment and Management of Environmental Pollution (AMEP) Sub-Programme of the Caribbean Environment Programme coordinates activities related to the Protocol Concerning Cooperation in Combating Oil Spills in collaboration with the Regional Marine Pollution Emergency, Information and Training Centre (REMPEITC-Caribe), the regional activity centre, established under the Cartagena Convention to address issues related to oil pollution and response. The Centre was established in Curaçao in 1995 within the framework of the Caribbean Environmental Programme and has been supported by the host Government (Netherlands Antilles and from 2011, Curaçao), as well as continuous secondments from United States and from France and temporary secondments from the

Table 7.3Status of ratification of the Cartagena Convention and the Oil Spill Protocol

| Contracting Parties | Cartagena Convention and its Oil Spill Protocol Ratified/Acceded |

| Antigua and Barbuda | Sept 1986 |

| Bahamas | June 2010 |

| Barbados | May 1985 |

| Belize | Sept 1999 |

| Colombia | March 1988 |

| Costa Rica | Aug 1991 |

| Cuba | Sep 1988 |

| Dominica | Oct 1990 |

| Dominican Republic | Nov 1998 |

| France | Nov 1985 |

| Grenada | Aug 1987 |

| Guatemala | Dec 1989 |

| Guyana | July 2010 |

| Haiti | – |

| Honduras | – |

| Jamaica | Apr 1987 |

| Mexico | Apr 1985 |

| Netherlands | Apr 1984 |

| Nicaragua | Aug 2005 |

| Panama | Nov 1987 |

| St. Kitts and Nevis | June 1999 |

| Saint Lucia | Nov 1984 |

| St. Vincent and the Grenadines | July 1990 |

| Suriname | – |

| Trinidad and Tobago | Jan 1986 |

| United Kingdom | Feb 1986 |

| United States of America | Oct 1984 |

| Venezuela | Dec 1986 |

| European Union | – |

Netherlands and Venezuela. Additional financial support for projects and activities has been provided by the IMO and UNEP-CAR/RCU.

REMPEITC-Caribe developed two Regional oil pollution contingency plans, the Caribbean Island OPRC Plan and the Central America OPRC Plan.

7.3.2.3 The Eastern Africa region

The Conference of Plenipotentiaries on the Protection, Management and Development of the Marine and Coastal Environment of the Eastern African Region held at UNEP headquarters in Nairobi from 17 to 21 June 1985, adopted the Final Act of the conference, which included:

–Convention for the Protection, Management and Development of the Marine and Coastal Environment of the Eastern African Region (Nairobi Convention).

–Protocol Concerning Co-operation in Combating Marine Pollution in Cases of Emergency in the Eastern African Region, and

–Protocol Concerning Protected Areas and Wild Fauna and Flora in the Eastern African Region.

The 1985 Convention and its Protocols entered into force on 30 May 1996.

The Conference of Plenipotentiaries and the Sixth Conference of Parties to the Nairobi Convention, which took place at the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) Offices at Gigiri in Nairobi Kenya, adopted on 31 March 2010:

–Amended Nairobi Convention for the Protection, Management and Development of the Marine and Coastal Environment of the Western Indian Ocean, and

–Protocol for the Protection of the Marine and Coastal Environment of the Western Indian Ocean from Land-Based Sources and Activities.

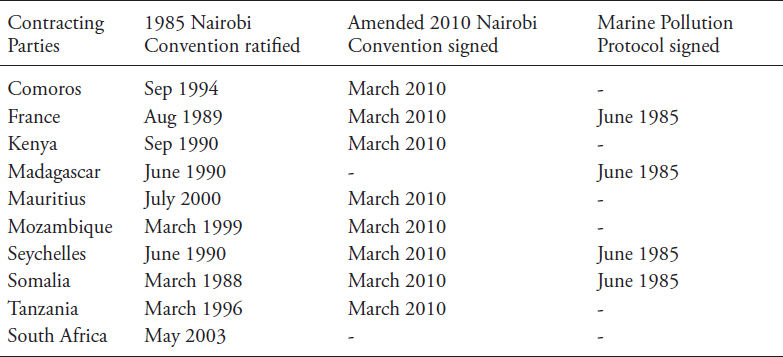

The ten countries of the region ratified the 1985 Nairobi Convention, whilst the Amended Nairobi Convention and the Marine Pollution Protocol have only been signed by some of the countries as set out in Table 7.4 below.

Table 7.4Status of ratification of the 1985 Nairobi Convention, the 2010 Amended Nairobi Convention and the Marine Pollution Protocol

The East African Action Plan was adopted in 1985 and came into force in 1986. It has since been ratified by all ten Eastern African countries. The Eastern African Regional Coordinating Unit, (EAF/RCU) located in the Seychelles, formally adopted in 1997, is responsible for the coordination of actions related to the protection of the marine environment.

Article 9 of the Emergency Protocol designates the Executive Director of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) to carry out those functions and activities.

On 26 October 2004, a National Centre, known as ‘Organe de Lutte contre l’Evènement de Pollution marine par les hydrocarbures’ (OLEP) was established in Madagascar. OLEP assumed responsibility for the coordination of the marine pollution emergency plan for the countries of the Western Indian Ocean.

As an outcome of the Western Indian Ocean Global Environment Facility (GEF) Marine Highway and Coastal and Marine Contamination Prevention Project (WIOMHCCP), implemented by the Indian Ocean Commission (IOC), a Workshop on the Regional Oil Spill Contingency Plan was held in Mauritius in October 2010 and the establishment of a Regional Coordination Centre was agreed. As of February 2013, seven Western Indian Ocean States, including Comoros, Kenya, Madagascar, Mauritius, Mozambique, Seychelles and Tanzania have signed the ‘Agreement on the Regional Contingency Plan for Preparedness for and Response to major Marine Pollution Incidents in the Western Indian Ocean’ and adopted the relevant Regional Contingency Plan.

The bid for South Africa to host the Regional Coordination Centre for Marine Pollution and Hazardous and Noxious Substances Preparedness and Response in the Western Indian Ocean Region was approved in 2011 to support the implementation of the Emergency Protocol.

7.3.2.4 West and Central Africa region

The Conference of Plenipotentiaries on Co-operation in the Protection and Development of the Marine and Coastal Environment of the West and Central African Region held in Abidjan, in March 1981 adopted the Action plan for the West and Central African Region as well as:

–The Convention for Co-operation in the Protection and Development of the Marine and Coastal Environment of the West and Central African Region known as the ‘Abidjan Convention’, and

–The Protocol concerning Co-operation in combating pollution in cases of emergency.

The Abidjan Convention and its Protocol came into force in 1984 following the ratification of these instruments as shown in Table 7.5.

Table 7.5Status of ratification of the Abidjan Convention the Protocol concerning Co-operation in combating pollution in cases of emergency

| Contracting Parties | Abidjan Convention and its Protocol ratified |

| Benin | Oct 1997 |

| Cameroon | March 1983 |

| Congo | Dec 1987 |

| Côte d’Ivoire | Jan 1982 |

| Gabon | Dec 1988 |

| Gambia | Dec 1984 |

| Ghana | July 1989 |

| Guinea | March 1982 |

| Guinea Bissau | Feb 2012 |

| Liberia | March 2005 |

| Mauritania | Apr 2012 |

| Nigeria | June 1984 |

| Senegal | May 1983 |

| Sierra Leone | June 2005 |

| South Africa | May 2002 |

| Togo | Nov 1983 |