THE CIVIL PROCESS

THE CIVIL PROCESS 5

Jarndyce [v] Jarndyce drones on. This scarecrow of a suit has, in the course of time, become so complicated that no man alive knows what it means. The parties to it understand it least; but it has been observed that no two Chancery lawyers can talk about it for five minutes without coming to a total disagreement as to all the premises. Innumerable children have been born into the cause; innumerable young people have married into it; innumerable old people have died out of it. Scores of persons have deliriously found themselves made parties in Jarndyce [v] Jarndyce, without knowing how or why; whole families have inherited legendary hatreds with the suit. The little plaintiff or defendant, who was promised a new rocking horse when Jarndyce [v] Jarndyce should be settled, has grown up, possessed himself of a real horse, and trotted away into the other world. Fair wards of court have faded into grandmothers; a long procession of Chancellors has come in and gone out … there are not three Jarndyces left upon the earth perhaps, since old Tom Jarndyce in despair blew his brains out at a coffee-house in Chancery Lane; but Jarndyce [v] Jarndyce still drags its dreary length before the Court, perennially hopeless [Bleak House, 1853, Charles Dickens].

Many critics believe that the adversarial system has run into the sand, in that, today, delay and costs are too often disproportionate to the difficulty of the issue and the amount at stake. The solution now being followed to that problem requires a more interventionist judiciary: the trial judge as the trial manager [Henry LJ, Thermawear v Linton (1995) CA].

5.1 INTRODUCTION

The extent of delay, complication and therefore expense of civil litigation may have changed since the time of Dickens’ observations about the old Court of Chancery, but how far the civil process is as efficient as it might be is a matter of some debate. In October 2010, governmental plans proposed that the Ministry of Justice’s budget be cut by 23 per cent. The staffing of courts is already inadequate but 14,250 of these frantically demanding jobs will go, leaving the residual workforce to toil in an arguably hopeless Sisyphean challenge.

In 2007, Judge Paul Collins, London’s most senior county court judge, said (February, Law in Action, BBC Radio 4) that low pay and high turnover among staff meant that serious errors were commonplace and routinely led to incorrect judgments in court. He said that with further cuts looming ‘we run the risk of bringing about a real collapse in the service we’re able to give to the people using the courts’.

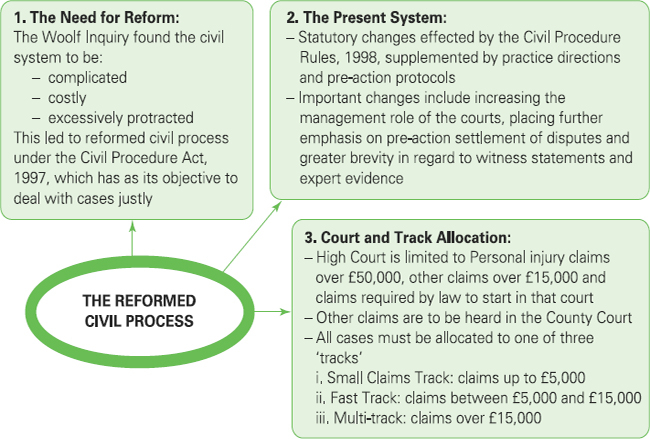

5.2 THE NEED FOR REFORM

A survey by the National Consumer Council in 1995 found that three out of four people in serious legal disputes were dissatisfied with the civil justice system (Seeking Civil Justice: A Survey of People’s Needs and Experiences, 1995, NCC). Of the 1,019 respondents, 77 per cent claimed the system was too slow, 74 per cent said it was too complicated and 73 per cent said that it was unwelcoming and outdated.

According to the Civil Justice Review (CJR) 1988, delay in litigation ‘causes continuing personal stress, anxiety and financial hardship to ordinary people and their families. It may induce economically weaker parties to accept unfair settlements. It also frustrates the efficient conduct of commerce and industry’. Despite some of the innovations in the five years following that CJR, the problems continued.

Historically, change has come very slowly and gradually to the legal system. The report of the CJR was largely ignored and, with the exception of a shift in the balance of work from the High Court to the county court (under the Courts and Legal Services Act (CLSA) 1990), no major changes came from its recommendations. The whole process began again with the Woolf Review of the civil justice system. In March 1994, the Lord Chancellor set up the Woolf Inquiry to look at ways of improving the speed and accessibility of civil proceedings, and of reducing their cost. Lord Woolf was invited by the government to review the work of the civil courts in England and Wales. He began from the proposition that the system was ‘in a state of crisis … a crisis for the government, the judiciary and the profession’. The recommendations he formulated – after extensive consultation in the UK and in many other jurisdictions – form the basis of major changes to the system that came into effect in April 1999. David Gladwell, head of the Civil Justice Division of the Lord Chancellor’s Department (LCD), stated (Civil Litigation Reform, 1999, LCD, p 1) that these changes represent ‘the greatest change the civil courts have seen in over a century’.

In the system that Lord Woolf examined, the main responsibility for the initiation and conduct of proceedings rested with the parties to each individual case, and it was normally the plaintiff (now claimant) who set the pace. Thus, Lord Woolf also noted:

Without effective judicial control … the adversarial process is likely to encourage an adversarial culture and to degenerate into an environment in which the litigation process is too often seen as a battlefield where no rules apply. In this environment, questions of expense, delay, compromise and fairness have only a low priority. The consequence is that the expense is often excessive, disproportionate and unpredictable; and delay is frequently unreasonable [Access to Justice, Interim Report, 1995, p 7].

The system had degenerated in a number of other respects. Witness statements, a sensible innovation aimed at ‘cards on the table’, began after a very short time to follow the same route as pleadings, with the drafter’s skill often used to obscure the original words of the witness. In addition, the use of expert evidence under the old system left a lot to be desired:

The approach to expert evidence also shows the characteristic range of difficulties: instead of the expert assisting the court to resolve technical problems, delay is caused by the unreasonable insistence on going to unduly eminent members of the profession and evidence is undermined by the partisan pressure to which party experts are subjected.

When Lord Woolf began his examination of the civil law process, the problems facing those who used the system were many and varied. His Interim Report published in June 1995 identified these problems. He noted, for example, that:

… the key problems facing civil justice today are cost, delay and complexity. These three are interrelated and stem from the uncontrolled nature of the litigation process. In particular, there is no clear judicial responsibility for managing individual cases or for the overall administration of the civil courts. Just as the problems are interrelated, so too the solutions, which I propose, are interdependent. In many instances, the failure of previous attempts to address the problem stems not from the solutions proposed but from their partial rather than their complete implementation [Access to Justice, Interim Report of Lord Woolf, 1995].

Many potential litigants are deterred from taking action by the high costs. It is also relevant to remember that whichever party loses the claim must pay for his own expenses and those of the other side; a combined sum which will, in many cases, be more than the sum in issue. An appeal to the Court of Appeal will increase the costs even further (in effect, fees and expenses for another claim) and the same may be true again if the case is taken to the Supreme Court (formerly House of Lords). There is in such a system a great pressure for parties to settle their claims. The CJR found that 90–95 per cent of cases were settled by the parties before the trial.

The cost of taking legal action in the civil courts has been gigantic. Two cases cited by Adrian Zuckerman in an address to Lord Woolf’s Inquiry illustrate the point. In one, a successful claim by a supplier of fitted kitchens to stop a £10,000 a year employee from taking up a job with a competitor cost the employer £100,000, even though judgment was obtained in under five weeks from the start of the proceedings. The expense of this case was in fact double the stated amount when the cost of the Legal Aid Fund’s bill for the employee’s defence was added to the total. In another case, a divorced wife had to pay £34,000 in costs for a judgment that awarded her £52,000 of the value of the family home.

It was the spiralling costs of civil litigation, to a large extent borne by the taxpayer through legal aid, which prompted the Lord Chancellor to move to cap the Legal Aid Fund. The legal aid budget rose from £426 million in 1987–88 to £1,526 million in 1997–98.

The system of civil procedure entails a variety of devices. Very complex cases may require the full use of many of these devices, but most cases could be tried without parties utilising all the procedures. Exorbitant costs and long delays often resulted from unduly complicated procedures being used by lawyers acting for parties to litigation. Zuckerman has argued that this problem arose from the fact that the legal system was evolved principally by lawyers with no concern for cost efficiency. In both the High Court and the county court, the system allowed parties to quarrel as much over procedural matters as the actual merits of the substantive dispute. In one case, for example, the issue of whether a writ had been properly served on the other side had to be considered by a Master (the High Court judicial officer empowered to deal with procedural matters) and then on appeal, by a judge, and then on another appeal, by the Court of Appeal. Thus, cost and delay could build up before the parties even arrived at the stage of having their real argument heard. If a claim or defence was amended, the fate of the amendment could take two appeal hearings to finally resolve. The pre-trial proceedings often degenerated into an intricate legal contest separate from the substantive issue.

The CJR 1988 recommended unification of the county courts and the High Court. It accepted the need for different levels of judiciary, but argued that having different levels of courts was inefficient. This recommendation carried what Roger Smith, then director of the Legal Action Group, called an ‘unspoken sting’, namely, that a divided legal profession could hardly survive a unified court. The Bar rebelled and the judiciary were solidly opposed to such change. The recommendation was not legislated.

The CLSA 1990, following other recommendations in the CJR, legislated for large numbers of cases in the High Court being sent down to the county courts to expedite their progress. No extra resources were given to the county courts to cope with the influx of cases and so, not surprisingly, there has been a growing backlog of cases and a poorer quality of service in the county courts. This problem may well have worsened rather than been helped by the introduction of the Civil Procedure Rules (CPR), as more cases are now heard in the county courts.

There were tactical reasons why parties were tempted to use the full panoply of procedural rules. The rule that ‘costs follow success’ (that is, the losing side usually has to pay the legal costs of the other side) can operate to encourage the building up of expense. Wealthy litigants could employ protracted procedures in an effort to worry poorer opponents to settle on terms determined by the former. Conditional fee arrangements (see below, at 14.11) have made very little impact on the system, so lawyers who are paid by the hour regardless of success are unlikely to be especially anxious about the speed and efficiency of their work.

5.3 THE NEW CIVIL PROCESS

Following the Civil Procedure Act 1997, the changes have been effected through the new Civil Procedure Rules (CPR) 1998, which came into force on 26 April 1999. These rules replaced the Rules of the Supreme Court 1965 and the County Court Rules 1981. The Rules are divided into parts and practice directions. There are also pre-action protocols. Each part deals with a particular aspect of procedure and within each part is a set of rules laying down the procedure relating to that aspect. Also, under most parts can be found new practice directions that give guidance on how the rules are to be interpreted. In addition, the rules are kept under constant review and there are regular updates; in January 2010, the fifty-first update was issued and in March 2010 the fifty-second. The former introduced many changes and the latter a small number. The fifty-third update was issued on 1 October 2010 and the fifty-fourth was introduced on 20 October 2010 with minor changes. The fifty-fifth update was introduced on 6 April 2011. This update has introduced a number of changes, which include part 45 to allow HM Revenue and Customs (HMRC) a fixed costs award for the recovery of money in the county court where the matter is conducted by an HMRC officer. Of major importance has been the accessibility of the CPR, which can be found on the LCD website, including practice directions and updates. A further method of improving the civil process has been the introduction of pre-action protocols for certain types of case, which are designed to increase the opportunity for settling cases as early in the proceedings as possible by improving communication between the parties and their advisers. The rules are quoted as, for example, ‘rule 4.1’, which refers to Part 4, r 1 of the CPR.

The reforms work towards conflict resolution as the main purpose for civil legal proceedings, rather than a case being a prolonged opportunity for lawyers to demonstrate a range of legalistic skills.

The principal parts of all of these new rules and guidelines are examined below.

The main features of the new civil process are as follows.

The Case Control

The progress of cases is monitored by using a computerised diary monitoring system. Parties are encouraged to co-operate with each other in the conduct of the proceedings; which issues need full investigation and trial are decided promptly and others disposed of summarily.

Court Allocation and Tracking

The county courts retain an almost unlimited jurisdiction for handling contract and tort claims. Where a matter involves a claim for damages or other remedy for libel or slander, or a claim where the title to any toll, fair, market or franchise is in question then the proceedings cannot start in the county court unless the parties agree otherwise. Some matters are expressly reserved to the county court such as Consumer Credit Act claims and money claims under £25,000.

Issuing proceedings in the High Court is now limited to personal injury claims with a value of £50,000 or more; other claims with a value of more than £25,000; claims where an Act of Parliament requires a claim to start in the High Court; or specialist High Court claims. The Ministry of Justice issued an Impact Assessment on 29 March 2011 to review the above financial limits.

Cases are allocated to one of three tracks for a hearing, that is, small claims, fast track or multitrack, depending on the value and complexity of the claim.

The Documentation and Procedures

Most claims will be begun by a multipurpose form and the provision of a response pack, and the requirement that an allocation questionnaire is completed is intended to simplify and expedite matters.

5.3.1 THE CIVIL PROCEDURE RULES

The CPR are the same for the county court and the High Court. The vocabulary is more user-friendly, so, for example, what used to be called a ‘writ’ will be a ‘claim form’ and a guardian ad litem will be a ‘litigation friend’.

Although in some ways all the fuss about the new CPR being so far-reaching creates the impression that the future will see a sharp rise in litigation, the truth may be different. During the last ten years, the sort of civil litigation that people mean when they speak about ‘compensation culture’ has gone down, not up. There are, incontrovertibly, thousands fewer such claims in the courts now than ten years ago. The Queen’s Bench Division of the High Court is the court that deals with all substantial claims in personal injury, breach of contract, and negligence actions. According to official figures (Judicial and Court Statistics 2010, Ministry of Justice, 30 June 2011), 153,624 writs and originating summonses were issued by the court in 1995. By 2010, however, the number of annual actions issued was down to 16,600. The number of claims issued in the county courts (which deal with less substantial civil disputes in the law of negligence) has also fallen. In 1998, the number of claims issued nationally was 2,245,324 but in 2010 it was 1,617,000.

5.3.2 THE OVERRIDING OBJECTIVE (CPR PART 1)

The overriding objective of the CPR is to enable the court to deal justly with cases. It applies to all of the rules and the parties to a case are required to assist the court in pursuing the overriding objective. Further, when the courts exercise any powers given to them under the CPR, or in interpreting any rules, they must consider and apply the overriding objective. The first rule reads:

1.1(1) These rules are a new procedural code with the overriding objective of enabling the court to deal with cases justly.

This objective includes ensuring that the parties are on an equal footing and saving expense. When exercising any discretion given by the CPR, the court must, according to r 1.2, have regard to the overriding objective and a checklist of factors, including the amount of money involved, the complexity of the issue, the parties’ financial positions, how the case can be dealt with expeditiously and fairly, and by allotting an appropriate share of the court’s resources while taking into account the needs of others. In future, as Judge John Frenkel observes (‘On the road to reform’ (1998)), ‘the decisions of the Court of Appeal are more likely to illustrate the application of the new rules to the facts of a particular case as opposed to being interpretative authorities that define the meaning of the rules’.

5.3.3 PRACTICE DIRECTIONS

Practice directions (official statements of interpretative guidance) play an important role in the new civil process. In general, they supplement the CPR, giving the latter fine detail. They tell parties and their representatives what the court will expect of them in respect of documents to be filed in court for a particular purpose, and how they must co-operate with the other parties to their action. They also tell the parties what they can expect of the court, for example, they explain what sort of sanction a court is likely to impose if a particular court order or request is not complied with. Almost every part of the new rules has a corresponding practice direction. They supersede all previous practice directions in relation to civil process.

5.3.4 PRE-ACTION PROTOCOLS

The pre-action protocols (PAPs) are an important feature of the reforms. They exist for cases of clinical disputes (formerly called medical/clinical negligence, but now extended to cover claims against dentists, radiologists, and so on) and personal injury, disease and illness, construction and engineering disputes, defamation, professional negligence, housing disrepair, housing possession following rent arrears, housing possession following mortgage arrears, low value personal injury claims in road traffic accidents and judicial review. Further protocols are likely to follow.

In the Final Report on Access to Justice (1996), Lord Woolf stated (Chapter 10) that PAPs are intended to ‘build on and increase the benefits of early but well informed settlements’. The purposes of the PAPs, he said, are:

(a) to focus the attention of litigants on the desirability of resolving disputes without litigation;

(b) to enable them to obtain the information they reasonably need in order to enter into an appropriate settlement;

…

(d) if a pre-action settlement is not achievable, to lay the ground for expeditious conduct of proceedings.

The protocols were drafted with the assistance of The Law Society, the Clinical Disputes Forum, the Association of Personal Injury Lawyers and the Forum of Insurance Lawyers. Most clients in personal injury and clinical dispute claims want their cases settled as quickly and as economically as possible. The new spirit of co-operation fostered by the Woolf reforms should mean that fewer cases are pushed through the courts. The PAPs are intended to improve pre-action contact between the parties and to facilitate better exchange of information and fuller investigation of a claim at an earlier stage. Both clinical disputes and personal injury PAPs recommend:

• the claimant sending a reasonably detailed letter of claim to the proposed defendant, including details of the accident/medical treatment/negligence, a brief explanation of why the defendant is being held responsible, a description of the injury and an outline of the defendant’s losses. Where the matter involves a road traffic accident, the name and address of the hospital where treatment was received along with the claimant’s hospital reference number should be provided. Unlike a ‘pleading’ in the old system (which could not be moved away from by the claimant), there will be no sanctions applied if the proceedings differ from the letter of claim. However, as Gordon Exall has observed (‘Civil litigation brief’ (1999) SJ 32, 15 January), letters of claim should be drafted with care because any variance between them and the claim made in court will give the defendant’s lawyers a fruitful opportunity for cross-examination;

• the defendant in personal injury cases should reply to the letter within 21 days of the date of posting, identify insurers if applicable and if necessary identify specifically anything omitted from the letter. The healthcare provider in clinical dispute cases should acknowledge the letter within 14 days of receipt and should identify who will be dealing with the matter. The defendant/healthcare provider then has a maximum of three months to investigate/provide a reasoned answer and tell the claimant whether liability is admitted. If it is denied, reasons must be given;

• within that three-month period or on denial of liability, the parties should organise disclosure of key documents. For personal injury cases, the protocol lists the main types of defendant’s documents for different types of cases. If the defendant denies liability, then he should disclose all the relevant documents in his possession, which are likely to be ordered to be disclosed by the court. In clinical dispute claims, the key documents will usually be the claimant’s medical records, and the protocol includes a proforma application to obtain these;

• the personal injury PAP also includes a framework for the parties to agree on the use of expert evidence, particularly in respect of a condition and prognosis report from a medical expert. Before any prospective party instructs an expert, he should give the other party a list of names of one or more experts in the relevant specialty that he considers are suitable to instruct. Within 14 days, the other party may indicate an objection to one or more of the experts; the first party should then instruct a mutually acceptable expert. Only if all suggested experts are objected to can the sides instruct experts of their own. The aim here is to allow the claimant to get the defendant to agree to one report being prepared by a mutually agreeable nonpartisan expert. The clinical dispute PAP encourages the parties to consider sharing expert evidence, especially with regard to quantum (that is, the amount of damages payable);

• both PAPs encourage the parties to use alternative dispute resolution (ADR) or negotiation to settle the dispute during the pre-action period.

At the early stage of proceedings, when a case is being allocated to a track (that is, small claims, fast track or multitrack), after the defence has been filed, parties will be asked whether they have complied with a relevant protocol, and if not, why not. The court will then be able to take the answers into account when deciding whether, for example, an extension of time should be granted. The court will also be able to penalise poor conduct by one side through costs sanctions – an order that the party at fault pay the costs of the proceedings or part of them.

5.4 CASE CONTROL (CPR PART 3)

Case control by the judiciary, rather than leaving the conduct of the case to the parties, is a key element in the reforms resulting from the Woolf Review. The court’s case management powers are found in Part 3 of the CPR, although there is a variety of ways in which a judge may control the progress of the case. A judge may make a number of orders to give opportunities to the parties to take stock of their case-by-case management conferences, check they have all the information they need to proceed or settle by pre-trial reviews, or halt the proceedings to give the parties an opportunity to consider a settlement. When any application is made to the court, there is an obligation on the judge to deal with as many outstanding matters as possible. The court is also under an obligation to ensure that witness statements are limited to the evidence that is to be given if there is a hearing, and expert evidence is restricted to what is required to resolve the proceedings. Judges receive support from court staff in carrying out their case management role. The court monitors case progress by using a computerised diary monitoring system which:

• records certain requests, or orders made by the court;

• identifies the particular case or cases to which these orders/requests refer, and the dates by which a response should be made; and

• checks on the due date whether the request or order has been complied with.

Whether there has been compliance or not, the court staff will pass the relevant files to a procedural judge (a Master in the Royal Courts of Justice, a district judge in the county court), who will decide if either side should have a sanction imposed on them.

In the new system, the litigants have much less control over the pace of the case than in the past. They will not be able to draw out proceedings, or delay in the way that they once could have done, because the case is subject to a timetable. Once a defence is filed, the parties get a timetable order that includes the prospective trial date. The need for pre-issue preparation is increased, and this benefits litigants because, as Professor Hazel Genn’s research has shown (Hard Bargaining: Out of Court Settlement in Personal Injury Claims (1987)), in settled personal injury actions, 60 per cent of costs were incurred before proceedings. The court now has a positive duty to manage cases. Rule 1.4(1) states that ‘The court must further the overriding objective by actively managing cases’. The rule goes on to explain what this management involves:

1.4(2) Active case management includes –

(a) encouraging the parties to co-operate with each other in the conduct of the proceedings;

(b) identifying the issues at an early stage;

(c) deciding promptly which issues need full investigation and trial and accordingly disposing summarily of the others;

(d) deciding the order in which issues are to be resolved;

(e) encouraging the parties to use an alternative dispute resolution procedure if the court considers that appropriate …;

(f) helping the parties to settle the whole or part of the case;

(g) fixing timetables or otherwise controlling the progress of the case;

(h) considering whether the likely benefits of taking a particular step justify the cost of taking it;

(i) dealing with as many aspects of the case as it can on the same occasion;

(j) dealing with the case without the parties needing to attend court;

(k) making use of technology; and

(l) giving directions to ensure that the trial of a case proceeds quickly and efficiently.

It is worth noting here that district judges and deputy district judges have had extensive training to promote a common approach (see above, at 5.4). Training is being taken very seriously by the judiciary. District judges now occupy a pivotal position in the civil process.

Part 3 of the CPR gives the court a wide range of substantial powers. The court can, for instance, extend or shorten the time for compliance with any rule, practice direction or court order, even if an application for an extension is made after the time for compliance has expired. It can also hold a hearing and receive evidence by telephone or ‘by using any other method of direct oral communication’.

The Association of District Judges, the Association of Personal Injury Lawyers and the Forum of Insurance Lawyers, who meet at six-monthly intervals to discuss how the operation of the CPR might be improved ((2000) 13 LSG 11), agreed that telephone hearings work very well (on the whole), but contested interim applications are often not suitable for telephone hearings and should not be disguised as case management conferences. Furthermore, not all courts have yet received the right equipment to be able to conduct a telephone hearing. The district judge cannot be put in the role of a go-between, which happens in some judges’ rooms where there is no conference facility but one party has attended in person and the opponent is on the other end of a standard telephone.

Part 3 of the CPR also gives the court powers to:

• strike out a statement of case;

• impose sanctions for non-payment of certain fees;

• impose sanctions for noncompliance with rules and practice directions;

• give relief from sanctions.

There is, though, a certain flexibility built into the rules. A failure to comply with a rule or practice direction will not necessarily be fatal to a case. Rule 3.10 of the CPR states:

Where there has been an error of procedure such as a failure to comply with a rule or practice direction:

(a) the error does not invalidate any step taken in the proceedings unless the court so orders; and

(b) the court may make an order to remedy the error.

The intention of imposing a sanction will always be to put the parties back into the position they would have been in if one of them had not failed to meet a deadline. For example, the court could order that a party carries out a task (like producing some sort of documentary evidence) within a very short time (for example, two days) in order that the existing trial dates can be met.

5.4.1 CASE MANAGEMENT CONFERENCES

Case management conferences may be regarded as an opportunity to ‘take stock’. Many of these are now conducted by telephone. There is no limit to the number of case management conferences that may be held during the life of a case, although the cost of attendance at such hearings against the benefits obtained will always be a consideration in making the decision. They will be used, among other things, to consider:

• giving directions, including a specific date for the return of a listing questionnaire;

• whether the claim or defence is sufficiently clear for the other party to understand the claim they have to meet;

• whether any amendments should be made to statements of case;

• what documents, if any, each party needs to show the other;

• what factual evidence should be given;

• what expert evidence should be sought and how it should be sought and disclosed; and

• whether it would save costs to order a separate trial of one or more issues.

5.4.2 PRE-TRIAL REVIEWS

Pre-trial reviews will normally take place after the filing of listing questionnaires and before the start of the trial. Their main purpose is to decide a timetable for the trial itself, including the evidence to be allowed and whether this should be given orally; instructions about the content of any trial bundles (bundles of documents including evidence, such as written statements, for the judge to read) and confirming a realistic time estimate for the trial itself.

Rules require that, where a party is represented, a representative ‘familiar with the case and with sufficient authority to deal with any issues likely to arise must attend every case management conference or pre-trial review’.

Both the Chancery Guide and the Queen’s Bench Guide provide that where it is estimated that a case will last more than 10 days or where a case warrants it the court may consider directing a pre-trial review.

5.4.3 STAYS FOR SETTLEMENT (CPR PART 26) AND SETTLEMENTS (CPR PART 36)

Under the new CPR, there is a greater incentive for parties to settle their differences. Part 36 sets out the procedure for either party to make offers to settle. A Part 36 offer can be made before the start of proceedings and also in appeal proceedings.

The party making the offer is called the ‘offeror’ and the party receiving it is called the ‘offeree’. Under the revised Part 36 rule where an offer relates to settlement of a money claim it is no longer possible to accompany the offer with the payment of funds into court. This provision applies irrespective of who the offeror is and whether that party has the means or assets to pay. When a Part 36 offer is accepted by the claimant the defendant must pay the sum offered within 14 days (unless the parties agree to extend the time period), failing which the claimant can enter judgment.

The court will take into account any pre-action offers to settle when making an order for costs. Thus, a side that has refused a reasonable offer to settle will be treated less generously in the issue of how far the court will order their costs to be paid by the other side. For this to happen, the offer must be one which is made to be open to the other side for at least 21 days after the date it was made (to stop any undue pressure being put on someone with the phrase ‘take it or leave it, it is only open for one day then I shall withdraw the offer’).

If an offer to settle is to be made in accordance with Part 36 it must be made in writing and state that it is intended to have the consequences of Part 36. Where the defendant makes the offer, it must specify a period of not less than 21 days within which the defendant will be liable for the claimant’s costs if the offer is accepted. In addition either party’s offer must state whether it relates to the whole or part of the claim, or to an issue which arises in it and if so to which part or issue and whether any counterclaim is taken into account. The revised Part 36 rule allows the parties to withdraw any offer after the expiry of the ‘relevant period’ as defined in Rule 36.3.1.c without the court’s permission. However, before the expiry of the ‘relevant period’ it is possible for a Part 36 offer to be withdrawn or its terms changed to be less advantageous to the ‘offeree’ only with the court’s permission.

Several aspects of the new rules encourage litigants to settle rather than take risks in order (as a claimant) to hold out for unreasonably large sums of compensation, or try to get away (as a defendant) with paying nothing rather than some compensation. The system of Part 36 payments or offers does not apply to a claim allocated to the small claim track but, for other cases, it seems bound to have a significant effect. Part 36 applies prior to a small claims track allocation and on reallocation from this track to the other two tracks.

Thus, if at the trial, a claimant does not get more damages than a sum offered by the defendant, or obtain a judgment more favourable than a Part 36 offer, the court will, unless it considers it unjust to do so, order the claimant to pay any costs incurred by the defendant after the latest date for accepting the payment or offer without requiring the court’s permission, together with interest on those costs.

Similarly, where at trial, a defendant is held liable to the claimant for a sum at least equal to the proposals contained in a claimant’s Part 36 offer (that is, where the claimant has made an offer to settle), the court may order the defendant to pay interest on the award at a rate not exceeding 10 per cent above the base rate for some or all of the period, starting with the date on which the defendant could have accepted the offer without requiring the court’s permission. In addition, the court may order that the claimant be entitled to his costs on an indemnity basis together with interest on those costs at a rate not exceeding 10 per cent above base rate for the period from the latest date when the defendant could have accepted the offer without requiring the court’s permission.

The court has a general and overreaching discretion to make a different order for costs than the normal order under Part 44.

District Judge Frenkel has given the following example:

Claim, £150,000 – judgment, £51,000 – £50,000 paid into court. The without prejudice correspondence shows that the claimant would consider nothing short of £150,000. The claimant may be in trouble. The defendant will ask the judge to consider overriding principles of Part 1 ‘Was it proportional to incur the further costs of trial to secure an additional £1,000?’. Part 44.3 confirms the general rule that the loser pays but allows the court to make a different order to take into account offers to settle, payment into court, the parties’ conduct including pre-action conduct and exaggeration of the claim [(1999) 149 NLJ 458].

Active case management imposes a duty on the courts to help parties settle their disputes. A ‘stay’ is a temporary halt in proceedings, and an opportunity for the court to order such a pause. Either party to a case can also make a written request for a stay when filing their completed allocation questionnaire. Where all the parties indicate that they have agreed on a stay to attempt to settle the case, provided the court agrees, they can have an initial period of one month to try to settle the case. If the court grants a stay, the claimant must inform the court if a settlement is reached, otherwise at the expiry of the stay it will effectively be deemed that a settlement has not been reached and the file will be referred to the judge for directions as considered appropriate.

The court will always give the final decision about whether to grant the parties more time to use a mediator or arbitrator or expert to settle, even if the parties are agreed they wish to have more time. A stay will never be granted for an indefinite period.

5.4.4 APPLICATIONS TO BE MADE WHEN CLAIMS COME BEFORE A JUDGE (CPR PART 1)

The overriding objective in Part 1 requires the court to deal with as many aspects of the case as possible on the same occasion. The filing of an allocation questionnaire, which is to enable the court to judge in which track the case should be heard, is one such occasion. Parties should, wherever possible, issue any application they may wish to make, such as an application for summary judgment (CPR Part 24), or to add a third party (CPR Part 20), at the same time as they file their questionnaire. Any hearing set to deal with the application will also serve as an allocation hearing if allocation remains appropriate.

5.4.5 WITNESS STATEMENTS (CPR PART 32)

In the Final Report on Access to Justice, Lord Woolf recognised the importance of witness statements in cases, but observed that they had become problematic because lawyers had made them excessively long and detailed in order to protect against leaving out something that later proved to be relevant. He said ‘witness statements have ceased to be the authentic account of the lay witness; instead they have become an elaborate, costly branch of legal drafting’ (para 55).

Witness statements must contain the evidence that the witness will give at trial. They should be drafted in lay language and should not discuss legal propositions. Witnesses will be allowed to amplify on the statement or deal with matters that have arisen since the report was served, although this is not an automatic right and a ‘good reason’ for the admission of new evidence will have to be established.

5.4.6 EXPERTS (CPR PART 35)

The rules place a clear duty on the court to ensure that ‘expert evidence is restricted to that which is reasonably required to resolve the proceedings’. That is to say that expert evidence will only be allowed either by way of written report, or orally, where the court gives permission. Equally important is the rules’ statement about experts’ duties. Rule 35.3 states that it is the clear duty of experts to help the court on matters within their expertise, bearing in mind that this duty overrides any obligation to the person from whom they have received instructions or by whom they are paid.

There is greater emphasis on using the opinion of a single expert. Experts are only to be called to give oral evidence at a trial or hearing if the court gives permission. Experts’ written reports must contain a statement that they understand and have complied with, and will continue to comply with, their duty to the court. Instructions to experts are no longer privileged and their substance, whether written or oral, must be set out in the expert’s report. Thus, either side can insist, through the court, on seeing how the other side phrased its request to an expert.

5.5 COURT AND TRACK ALLOCATION (CPR PART 26)

Part 7 of the CPR sets out the rules for starting proceedings. A new restriction is placed on which cases may be begun in the High Court. The county courts retain an almost unlimited jurisdiction for handling contract and tort claims (that is, negligence cases, nuisance cases but excluding a claim for damages or other remedy for libel or slander unless the parties agree otherwise). Issuing proceedings in the High Court is now limited to:

• personal injury claims with a value of £50,000 or more; other claims with a value of more than £25,000 (this limit is now under review – see paragraph 5.3);

• claims where an Act of Parliament requires proceedings to start in the High Court; or

• specialist High Court claims which need to go to one of the specialist ‘lists’, like the Commercial List, the Technology and Construction List.

The new civil system works on the basis that the court, upon receipt of the defence, requires the parties to complete ‘allocation questionnaires’ (giving all the relevant details of the claim, including how much it is for and an indication of its factual and legal complexity). Under Part 26 of the CPR, the case will then be allocated to one of three tracks for a hearing. These are: (a) small claims track; (b) fast track; and (c) multitrack. Each of the tracks offers a different degree of case management. The multitrack has, since 6 April 2009, a minimum limit of £25,000.01.

The small claims limit is £5,000, although personal injury and housing disrepair claims for over £1,000, illegal eviction and harassment claims will be excluded from the small claims procedure. The limit for cases going into the fast track system is £25,000. Applications to move cases ‘up’ a track on grounds of complexity will have to be made on the allocation questionnaire (see below).