The Association, Cooperation, Partnership, and Trade Agreements Before the EU Courts: Embracing Maximalist Treaty Enforcement?

III

The Association, Cooperation, Partnership, and Trade Agreements Before the EU Courts: Embracing Maximalist Treaty Enforcement?

1. Introduction

This chapter assesses the EU Courts’ case law in what has been the vast bulk of their activity concerning EU Agreements, namely, the Association, Cooperation, Partnership, and Trade Agreements (henceforth, for ease of reference, Trade Agreements). This body of case law, a total of 184 cases,1 developed at a remarkable rate following the early batch of cases that culminated with the bold Kupferberg ruling. This chapter aims to redress an existing gap in the literature whereby particular EU Trade Agreement judgments are singled out for praise or criticism without situating them within the broader framework of the case law. This accordingly also creates a key pillar for the empirically grounded overall assessment of the judicial treatment accorded EU Agreements which constitutes a core objective of this book. It is only in this fashion that one can assess whether the lofty judicial language commencing with Haegeman II, and for many the promise that the full enforcement arsenal of EU law would be unleashed for policing this additional category of EU law, has been adhered to in judicial practice.

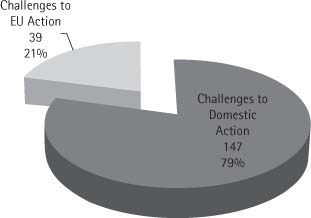

The chapter is divided into two main sections. The first assesses preliminary rulings, where the bulk of EU Court activity has occurred (131 cases), and the second direct actions, that is, actions commencing and terminating before the EU Courts in Luxembourg (53 cases).

2. Preliminary Rulings

The preliminary rulings jurisprudence in the EU Trade Agreement context can be divided into two core categories involving, respectively, challenges to domestic action or to EU action.

2.1 Challenges to domestic action

The Trade Agreement case law challenging domestic measures can be divided into three categories concerning, respectively, provisions pertaining, first, to trade in goods, where the EU Trade Agreement jurisprudence commenced, secondly, to movement of persons which rapidly became the dominant sources of litigation activity, and, thirdly, to a small generic category concerning neither of the aforementioned provisions.

2.1.1 Provisions pertaining to goods

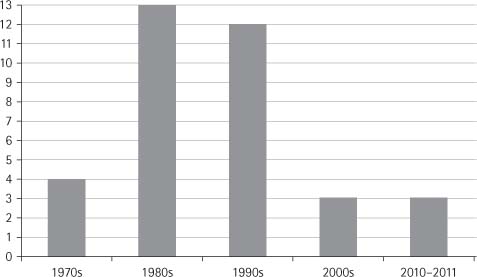

The case law concerning provisions pertaining to goods has given rise to 35 rulings, 27 of which have come since Kupferberg. The number of rulings by decade is represented in Figure III.1, with only six having arisen since 1997.

Through to the emphatic Kupferberg ruling in 1982 only two specific EU Agreement provisions had been expressly found directly effective: the customs duty prohibition in the Yaound Convention (Bresciani), and the fiscal discrimination prohibition in both the Greek Association Agreement and the Portugal Trade Agreement (Pabst and Kupferberg). These types of provision have given rise to a further six preliminary rulings, two pertaining to the customs duty prohibition,2 and four for the fiscal discrimination prohibition.3 In none were the questions framed in terms of direct effect and in all six the ECJ provided interpretations without expressly conceptualizing matters in such terms.

Figure III.1 Preliminary rulings challenging domestic action and concerning goods-related provisions in EU Trade Agreements (35 cases, 1970–2011 (03/10/11))

As far as the non-fiscal discrimination provision is concerned, in the first two cases the Court’s reading preserved the national measure at issue.4 The second of the cases, Metalsa, is the more significant for current purposes. It concerned whether an interpretation accorded to Article 110 TFEU applied to its counterpart in the Austria Trade Agreement.5 The Commission and the Member State whose legislation was at stake successfully argued, invoking Polydor, against such an interpretative transposition. The ECJ concluded that the interpretation accorded the EU provision was based on the aims of the Treaty including the establishment of a common market which were not part of the Austria Agreement and was accordingly unwilling to countenance the same interpretation.6 The third case, the Texaco ruling, saw the ECJ asked effectively whether a certain charge was consistent with the customs duty prohibition (Art 6) and the fiscal discrimination prohibition (Art 18) in the Sweden Agreement and Agreements containing corresponding provisions. Little attention was given to the customs duty prohibition, but the ECJ invoked Kupferberg and the identical fiscal discrimination prohibition at issue in that case in concluding that the charge was contrary to Agreements containing provisions similar to the fiscal discrimination prohibition in the Sweden Agreement. The fourth was a recent domestic damages action in which the ECJ curiously expressly asserted that it only needed to engage with the scope of the non-fiscal discrimination provision of the first Yaoundé Convention (Art 14) and not its direct effect.7 A reading of that provision was proffered preserving the validity of the relevant domestic tax in this context.8

In both the customs duty prohibition cases the interpretations given made it clear that domestic measures breached EU Agreements. The first, Legros, established that certain ‘dock dues’ constituted a charge having an equivalent effect to a customs duty in breach of the EU Treaty. France argued, invoking Polydor, that it did not follow that this also rendered it a prohibited charge under the Sweden Agreement. The Court underscored that the Agreement would be deprived of much of its effet utile if the term were interpreted as having a more limited scope than its EU law counterpart. The second case made it clear that this interpretative transposition of the term ‘charge’ applied to all EU Trade Agreements containing such a prohibition.9

On several occasions prior to Kupferberg, the ECJ interpreted provisions in EU Trade Agreements on quantitative restrictions (QRs) and measures having equivalent effect to quantitative restrictions (MEQRs) without first asking whether they were directly effective or conferred rights.10 The five additional preliminary rulings continued in this vein11 but one is worthy of additional comment. In Bulk Oil a UK court asked several questions concerning the Cooperation Agreement with Israel.12 At issue was the then UK policy precluding exports of crude oil to certain countries, a policy to which a contract between two firms had linked a sale and which led to litigation and the reference for a preliminary ruling. The relevance of the Cooperation Agreement to this sensitive dispute was easily dispensed with. The ECJ, following the UK and Commission submissions, concluded that it did not contain provisions expressly prohibiting export QRs/MEQRs.13 The case shares a clear parallel with the Polydor judgment in that a judicial interpretation preserving the national measure at issue was proffered while sidestepping the express direct effect question, including its particularly controversial horizontal manifestation.14

Nine cases have concerned rules of origin provisions, in none of which did the domestic court frame its question in terms of direct effect, instead seeking only interpretations of provisions in disputes in which disgruntled traders challenged decisions of, inter alia, customs authorities.15 In one, the ruling made clear that the domestic customs authority decision was invalid but without addressing the relevant Agreement.16 Of the remaining eight, in seven the Court interpreted the relevant provisions without, like the Advocate General before it, framing matters in terms of direct effect.17 The remaining case, where direct effect was explored, merits additional comment.

The 1994 Anastasiou judgment saw the ECJ and the Advocate General expressly respond to the UK and Commission submissions that the provisions invoked were not directly effective concerning, as they did, administrative cooperation between customs authorities; a rather counter-intuitive argument given that the Court had already proffered interpretations of similar provisions in Agreements with Switzerland, Yugoslavia, and Austria18 that effectively proscribed domestic customs authorities decisions. The explanation for such argumentation lies in the controversial nature of the dispute. It concerned a judicial challenge based on the Cyprus Association Agreement—which Greece supported before the ECJ—to the UK practice of permitting certain imports from the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus19 to benefit from the Agreement’s preferential tariffs.

The judgment commenced with invocation of the direct effect test for EU Agreements which provides that a provision ‘must be regarded as having direct effect when, regard being had to its wording and the purpose and nature of the agreement itself, the provision contains a clear and precise obligation which is not subject, in its implementation or effects, to the adoption of any subsequent measure.’20 Applying the test, the Court pointed to the aim of the Agreement, which was the progressive elimination of obstacles to trade, and the rules of origin play an essential role in determining which products benefit from preferential treatment. The rules were asserted, without explanation, to lay down clear, precise, and unconditional obligations. Two of the earlier EU Agreement rules of origin cases were cited, with the ECJ noting that this by implication showed that similar provisions could be applied by national courts. It was accordingly concluded that the provisions had direct effect.

Anastasiou shed important light on the ECJ’s then emerging approach to EU Agreements. The judicial approach to EU law provisions has been characterized (in Chapter I) as a maximalist model in which, amongst other things, the link between individual rights stricto sensu and direct effect was gradually discarded. Anastasiou sat comfortably within that evolving framework. The provisions concerned administrative cooperation between importing and exporting customs authorities rather than, as the UK and Commission’s logic would have it, individual rights for traders and producers of Republic of Cyprus goods enforceable before domestic courts. Expressly rejecting this argument indicated that the judicial approach to EU Agreements was developing in line with the approach to EU law proper. As Judge Pescatore once argued, direct effect is the normal state of the law and ultimately it is a question of whether a rule is capable of judicial adjudication.21 This presumption of justiciability equally appeared to be taking hold in certain dimensions of the Trade Agreement jurisprudence.

Four further cases involving the finer points of customs law have also arisen, in none of which were the questions or the responses framed in terms of direct effect.22 One, Deutsche Shell,23 was notable in that a German court asked several questions pertaining, inter alia, to a Transit Agreement with EFTA States and a recommendation of the Joint Committee established to administer it. The Court first asserted its interpretative jurisdiction over non-mandatory measures of bodies established by EU Agreements, considering them to be directly linked to the Agreement itself and thus forming part of the EU legal order.24 The ECJ ruled that it was not precluded from ruling on the interpretation of a non-binding measure in Article 267 proceedings,25 and whilst acknowledging that Joint Committee recommendations do not confer domestically enforceable individual rights, national courts were obliged to take them into consideration.26

An Italian consumption tax on bananas from non-member countries generated litigation in Italian courts which sought preliminary rulings on the compatibility of the legislation mainly with the common commercial policy.27 The Italian magistrates had not put forth any question as to the compatibility with EU Trade Agreements, but both the Commission and traders invoked EU Agreements. The ECJ gave a strong signal that the legislation breached the Lomé Convention (Art 139(2)), and that domestic courts should disregard national law incompatible with EU provisions contained in Agreements conferring rights on individuals. The manner in which the ruling was framed would inevitably invite further rulings and a different Italian court asked whether the Lomé Conventions confer domestically enforceable rights and whether the consumption tax was incompatible therewith.28 Italy argued that the Lomé Conventions did not contain provisions conferring domestically enforceable individual rights.29 But the other intervening Member State, the Commission, and the Advocate General, all appropriately pointed to the Bresciani judgment on a predecessor Agreement. The ECJ predictably reiterated Bresciani in holding that the Lomé Convention at issue may contain provisions conferring domestically enforceable individual rights. The relevant standstill clause was then held to be worded in clear, precise, and unconditional terms upon which individuals could rely and which precluded tax increases on banana imports from ACP States.30

Finally, in Katsivardas a Greek court asked whether an individual trader could plead the incompatibility of a national law with the most-favoured-nation clause in a Cooperation Agreement with several Latin American countries.31 The ECJ predictably reiterated an earlier ruling rejecting the direct effect of the equivalent provision in the successor Agreement;32 a decision considered equally valid for the most-favoured-nation clause of the predecessor Agreement.

2.1.2 Provisions pertaining to the movement of persons

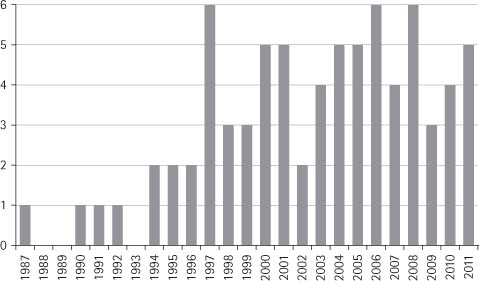

Provisions pertaining to the movement of third country nationals in EU Trade Agreements have given rise to 77 rulings with only one prior to 1987 (Razanatsimba). The activity since the second of these rulings in 1987—a trickle of cases in the early 1990s and growing substantially since then—is represented in Figure III.2:

Figure III.2 Preliminary rulings challenging domestic action and concerning persons-related provisions in EU Trade Agreements (76 cases, 1987–2011 (03/10/11))

This case law can be broken down into four core categories that will each be taken in turn.

2.1.2.1 Provisions specific to the Turkey Agreement

Revisiting Demirel and Sevince Provisions pertaining to the movement of Turkish nationals first arose in the Demirel judgment.33 A Turkish woman who entered Germany on a short visitation visa and lived with her husband, a lawfully employed Turkish worker, challenged an expulsion order. The German court asked whether certain Turkey Agreement provisions prohibited these new restrictions affecting resident Turkish workers. The UK and Germany argued that the free movement of workers provisions of this mixed agreement were commitments entered into by the Member States exercising their own powers and which the ECJ was not competent to interpret. The ECJ responded by holding that Article 217 TFEU empowered the EU to guarantee commitments in all fields, of which free movement of workers was one, covered by the Treaty of Rome. It in effect viewed the EU as having exercised that competence in concluding this Agreement via Article 217 TFEU.34

The now classic two-part direct effect test was articulated and its application commenced with the ECJ pointing to the various stages of the Agreement. Looking to its structure and content, it was found to be characterized by setting out the Association’s aims and guidelines for their attainment without establishing the detailed rules for doing so and with decision-making powers for their attainment being conferred on the Association Council. Turning to the specific provisions invoked, the first (Art 12) provided that the Contracting Parties agreed to be guided by the EU Treaty provisions on free movement of workers for the purposes of progressively securing freedom of movement of workers, while the second, in a Protocol to the Agreement (Art 36), provided that this was to be secured in progressive stages and that the Association Council was to decide on the necessary rules.35 The conclusion that followed was that these provisions set out a programme and were not sufficiently precise and unconditional.

Four Member States and the Commission had intervened against direct effect, and the Advocate General reached the same conclusion, in a textually irreproachable argument. Implementing decisions for the said rules had simply not been forthcoming. And a Reyners-type conclusion where, in the internal EU law context, the Court was unwilling to let the absence of explicitly textually envisaged implementation measures impede ‘one of the [EU’s] fundamental legal provisions’ was never a likely eventuality.36 Implementation of the free movement of workers objectives of the Agreement had been thrown wildly off track as a result of the global economic shocks of the 1970s and their consequences for the labour requirements of West European industry, combined with the 1980 coup in Turkey and Greece’s EU accession.

Nevertheless, the Association Council adopted Decision 2/76 pertaining mainly to the access to employment of Turkish workers and their family members which was superseded in 1980 by Decision 1/80 which expressly sought to revitalize the Association. These two Decisions were the subject of litigation shortly after Demirel. The Sevince ruling concerned a Turkish national challenging a residence permit refusal, invoking the two Association Council Decisions, in a Dutch court which referred questions as to their interpretation.37 The two intervening Member States, the Netherlands and Germany, were split on jurisdiction; the former siding with the Commission in arguing that Association Council Decisions were acts of the institutions for which there was preliminary ruling jurisdiction, and the latter contesting this by arguing that the Association Council is an autonomous institution with a different identity to that of the EU institutions. This was a powerful textual objection to jurisdiction, however, less than a year earlier in a direct action in which Germany had not intervened, it was held that a particular Turkey Association Council Decision, being directly connected with the Agreement, formed from its entry into force an integral part of the EU legal system.38 The ECJ invoked that ruling and further held, citing Haegeman II, that since it has jurisdiction to give preliminary rulings insofar as Agreements are acts adopted by the institutions it likewise has jurisdiction over the interpretation of decisions adopted by authorities established by Agreements and with responsibility for their implementation. That the latter proposition does not in itself follow from the former, obviously did not trouble the Court. And Germany would take little consolation that the textually indefensible argument that such Decisions are indeed acts of the EU institutions was not adopted,39 given that the practical consequences are indistinguishable.40

The Court then turned to the specific provisions which both Germany and the Netherlands, in contrast to the Commission, argued were not directly effective. The provisions at stake provided Turkish workers with certain rights depending on the length of their employment in the relevant Member State (Art 2(1)(b) of Decision 2/76 and Art 6(1) of Decision 1/80) and prohibited the introduction of new employment access restrictions (Art 7 of Decision 2/76 and Art 13 of Decision 1/80). It was held that Association Council Decision provisions would have to satisfy the same direct effect conditions as those applicable to the Agreement itself. The ECJ merely paraphrased the first batch while referring to them as upholding ‘in clear, precise and unconditional terms, the right of a Turkish worker …’, whilst the second batch were referred to as ‘contain[ing] an unequivocal standstill clause’. Direct application was held to be confirmed by the purpose and nature of the Association Council Decisions and the Turkey Agreement. The fact that the Decisions were intended to implement the Turkey Agreement provisions recognized as programmatic in Demirel was also noted, the logic seemingly being that they serve to concretize the programmatic norms. Following the Advocate General, several arguments against direct effect were then rejected: first, provisions in the Decisions providing that the procedure for applying the relevant provisions are to be established under national law did not empower Member States to restrict the application of precise and unconditional rights granted to Turkish workers by the Decisions; secondly, provisions in the Decisions providing that the Contracting Parties are to take any measures required for implementation merely emphasizes the obligation to implement in good faith; thirdly, the non-publication of the Decisions may prevent their application to a private individual but not their enforcement by a private individual vis-à-vis a public authority; fourthly, the safeguard provisions only apply to specific situations. Direct effect of the relevant provisions was then confirmed.41

The self-interest of the two States putting forward the direct effect objections is not difficult to discern: of the Turkish citizens residing in the EU some 90 or so per cent did so in Germany (in the mid-1980s),42 with the largest percentage of the remainder residing in the Netherlands. But such self-interest should not detract from the cogency of some of the arguments advanced. Provisions clearly calling for both EU and domestic implementing measures had not been pursued; the safeguards clause was of a unilateral nature and did not require any authorization from the Association Council; and the EU institutions had not published the two Decisions at issue which could be seen as indicative of the non-judicially applicable status intended.43 Given these factors, it would be difficult to conclude that the Contracting Parties (in reality the Member States) intended Association Council Decisions to be directly effective.44 The judgment evoked a similar dynamic to the maximalist enforcement model characterizing internal EU law, a model which, as in Sevince and Kupferberg, has frequently developed in the face of powerful contrary submissions from Member States. For precisely this reason, it has been criticized as a manifestation of judicial activism employing dubious reasoning.45

Post-Sevince case law on Articles 6 and 7 of Decision 1/80 The Court has addressed direct questions from national courts pertaining to the Association Council Decision provision (Art 6(1)) first held directly effective in Sevince on 21 occasions,46 and in addition offered a detailed interpretation of that provision in responding to a question on a different provision.47 Of these 22 cases, six included national court questions regarding Article 7 of Decision 1/80.48 The first paragraph of Article 7 concerns certain employment entitlements for family members of Turkish workers conditional on the length of their legal residence, and the second concerns employment entitlements for Turkish workers’ children conditional on their completion of vocational training in the Member State and one of their parents having completed a three-year period of legal employment there. It is useful at this point to digress momentarily with respect to the conceptually and substantively similar Article 7 line of case law. Aside from the aforementioned six judgments that also saw questions raised regarding Article 7, there have been an additional 11 cases in which national courts have raised Article 7.49 Thus, together this Article 6 and Article 7 jurisprudence has yielded a further 33 post-Sevince judgments. Both paragraphs of Article 7 were held directly effective in two cases in which the national courts did not frame their questions in such terms but appeared to assume they were directly effective; the Court’s reasoned justification amounted to an assertion that, like Article 6(1), the relevant provisions clearly, precisely, and unconditionally embodied the rights of Turkish workers’ children and conferred rights on their family members and were directly effective like Article 6(1).50 This was perhaps a foregone conclusion given the previous direct effect finding in Sevince on the related Article 6 question, but it remains noteworthy that direct effect was so casually established (and via Chamber rulings).

Certain key traits emerge from this batch of 33 judgments on Articles 6 and 7. First, in none were the questions expressly framed in terms of direct effect and yet in 26 rulings the ECJ has either asserted or expressly reiterated its direct effect holding, and in the remaining seven, whilst the language of direct effect was not expressly employed, reference to the conferral of rights by the relevant provisions was.51 Secondly, in 26 cases the domestic action challenged came from Germany.52 Germany has intervened in all bar two of the cases,53 usually seeking, mostly unsuccessfully, a restrictive reading.54 Thus, in the first post-Sevince case, the Kus case concerning Article 6(1), as well as seeking unsuccessfully to reiterate the argument against jurisdiction over Association Council Decisions employed in Sevince, Germany contested any inherent correlation between a right of access to employment and a residence permit.55 The ECJ, however, relied on the 1964 Free Movement of Workers Directive (64/221/EEC), and a judgment on the EU free movement provisions,56 in holding that a right of residence is indispensable to access to paid employment and concluded that a Turkish worker who fulfilled the Article 6(1) requirements could rely on it to obtain both a work permit and residence permit renewal. The judgment was equally notable for finding that the reason a Turkish worker is legally resident is irrelevant to the renewal of a work permit.57

Sharpston appropriately underscored the significance of this ruling:

Traditionally Member States retain the right to determine, not only access to their territory, but also the right to stay and reside there. That right has already disappeared in relation to [EU] nationals exercising rights of free movement. Now … third country nationals claiming rights under an association agreement may also acquire entrenched rights, which defeat the ordinary immigration policy of the Member State concerned.58

The Kus reading expressly linking the work permit and residence permit was transposed in the very next judgment to Article 7(2) concerning the rights of the children of Turkish workers, as was the finding, contrary to German submissions, that the right to respond to employment offers was not conditioned upon the grounds on which entry was originally granted.59

Of the remaining Article 6 and Article 7 cases, many involved transposing internal EU law principles and/or the Court responding with bold interpretations frequently in the face of contrary Member State submissions. The 1995 Bozkurt ruling was particularly significant, for here the ECJ first emphasized that it was essential to transpose as far as possible the principles enshrined in the Treaty provisions on free movement of workers to Turkish workers enjoying rights conferred by Decision 1/80. It is true that Article 12 of the Agreement expressly refers to the Contracting Parties agreeing to be guided by the EU Treaty free movement of workers provisions for progressively securing freedom of movement for workers,60 but it is contestable whether this provides a sufficient anchor for the extent of judicially created interpretative borrowing.61 In Bozkurt itself, in line with the Commission and contrary to the four intervening Member States, the internal EU law meaning of legal employment was transposed to Article 6(1) of Decision 1/80,62 later followed by the EU meaning of a ‘worker’ and a ‘family member’ being transposed, respectively, to Article 6(1) and Article 7 of Decision 1/80.63 In Tetik it was concluded, in line with Commission submissions but in opposition to the Advocate General and the submissions from the three intervening Member States (Germany, the UK, and France) and the Land Berlin, that a Turkish worker who fulfilled the four-year legal employment period in Article 6(1) did not forfeit rights by leaving employment on personal grounds and searching for new employment for a reasonable period;64 strikingly, the analogy with internal EU law concerned a case outlining that EU nationals should be given a reasonable time to apprise themselves of offers of employment but without acknowledging or explicating how this was relevant when dealing with someone entering the host State for the first time as opposed to someone already employed in the relevant State.65 Nor are these rights forfeited through temporary interruptions resulting from both suspended and non-suspended prison sentences, the Court having sought to interpret the public policy, public security, or public health exception in Decision 1/80 (Art 14(1)) analogously with the almost identically phrased Article 45(3) TFEU exception.66

In addition, important judgments have established that the rights for family members and children are not forfeited because of the attainment of adulthood and independent living. This conclusion was initially reached contrary to German submissions.67 Crucially, it was reiterated against strong opposition from several Member States and a national court contesting such reasoning as incompatible with Article 59 of the Additional Protocol providing for Turkey not to receive more favourable treatment than that granted under EU law between Member States.68 That ruling arguably deprived Article 59 of its natural meaning and was further consolidated when it later held that the child of Turkish workers who had returned with her parents to Turkey and returned alone to Germany ten years later, when over 21, to continue with and duly complete a vocational higher education course, was entitled to rely on the right of access to the employment market and a residence permit.69

A final case worthy of particular mention saw the Court faced with four Member States arguing that Turkish nationals who had not entered the host State as workers could not rely on Article 6(1).70 The strenuous Member State objections, including that an adverse judgment would lead them to restrict their policy of admitting Turkish students and au pairs, were to no avail for in Payir the ECJ held, in line with the Commission submissions but contrary to the Advocate General as concerned students, that being granted leave to enter as an au pair or student cannot deprive them of the status of worker and being duly registered as belonging to the labour force under Article 6(1).

Cases on the standstill clauses in Decision 1/80 and the Additional Protocol The employment restrictions standstill clause (Art 13) held directly effective in Sevince has led to three further preliminary rulings. The first was in Abatay & Sahin where the Court engaged with both that provision and the services and establishment standstill clause in the Additional Protocol (Art 41(1)).71 It held that the former standstill clause was not applicable to the facts,72 while rejecting a textually viable argument that it only operated with respect to those already in lawful employment.73 The services and establishment clause had been held directly effective in the earlier Savas judgment where a UK court put forth questions as to its direct effect and that of Article 13 of the Agreement (the freedom of establishment counterpart to Art 12 which had been held not directly effective in Demirel).74 The five intervening Member States, the Commission, and the Advocate General were against direct effect for the latter provision and the ECJ followed suit invoking the same reasoning as in Demirel.

The two remaining post -Sevince rulings on the employment restrictions standstill clause stemmed from questions from the Dutch Council of State framed in terms of the interpretation of that provision. In the first, the Court did not employ express direct effect language but did underscore that the standstill clause could be relied on before Member State courts, and concluded that it precluded the introduction of national legislation making the granting of residence permits or their extension conditional on disproportionate charges compared to those for EU nationals.75 The second paid no customary lip-service to direct effect.76 The basic issue in Toprak & Oguz was whether national provisions on the acquisition of residence permits introduced after the entry into force of Decision 1/80 and relaxing the provisions applicable on its entry into force could be tightened without being any more restrictive than the rules applicable when Decision 1/80 entered into force. Unsurprisingly, the Member State defending its new regime did so precisely on the ground that the relevant date was when the Decision entered into force (1 December 1980), a position supported by Germany and Denmark. Creative judicial interpretation followed with the Court finding that the relevant date to assess whether new rules gave rise to ‘new restrictions’ was when the new rules were adopted.77 In effect, any liberalization post-1 December 1980, sets a new benchmark from which a Member State can no longer retreat. To reach this conclusion, the Court relied on the objectives pursued by Article 13 as it articulated them, reiterating earlier judgments, creating conditions conducive to the gradual establishment of freedom of movement of workers, the right to establishment, and the freedom to provide services by prohibiting national authorities from creating new obstacles to those freedoms. The critic might well emphasize that none of these objectives are actually directly apparent on a reading of Decision 1/80. That the Court bolstered its conclusion by relying on equally generous interpretations of internal EU law standstill clauses, will be disconcerting for Member States seeking to defend their measures insofar as it further attests to the cross-fertilization from internal to external EU law.78

The services and establishment standstill clause first held directly effective in Savas has led to three further preliminary rulings reiterating its direct effect.79 The first (Tum) and second (Soysal) were of considerable consequence. The significance of Soysal, where the standstill clause was held to preclude a German visa requirement for Turkish nationals which did not exist when the Additional Protocol entered into force, is touched on in Section 2.2. In Tum Turkish nationals challenged decisions refusing their entry into UK territory to establish themselves in business and ordering them to leave. This refusal resulted from the application of new immigration rules. Only three Member States intervened, two of which argued, relying on Savas, which convinced the Advocate General, that Member States were exclusively competent to determine who is permitted lawful first entry and that the standstill clause could only be invoked by those lawfully present. The ECJ held that whilst the standstill clause does not confer a right of entry and does not render inapplicable the relevant substantive law it replaces, it operates as a quasi-procedural rule stipulating ratione temporis which Member State legislative provisions apply in this context. Or in plainer English, the standstill clause required the new immigration rules to give way and that those in force in 1973 be applied instead. The Court insisted that this did not call into question Member State competence to conduct their national immigration policy and that the mere fact that the clause imposed a duty not to act which limits their room for manoeuvre did not mean that the very substance of their sovereign competence in respect of aliens was undermined. To many Member States this distinction will ring hollow, for it further intrudes in the applicability of their immigration policy, as far as Turkish nationals are concerned.80

Article 9 of Decision 1/80: Turkish children and access to education and educational benefits The final judgment to consider is the Gürol ruling.81 A German court asked a direct question as to the direct effect and interpretation of the first sentence of Article 9 of Decision 1/80. This provides that Turkish children resident with parents who are or have been legally employed in the Member State are to be admitted to general education, apprenticeship, and vocational training courses under the same educational entry qualifications as children of Member State nationals. Germany and Austria, alongside the Commission and the Advocate General, accepted that the first sentence was directly effective and the Court unsurprisingly followed suit. But, strikingly, it went on to hold the second sentence to be directly effective which provides that ‘They [the children] may in that Member State be eligible to benefit from the advantages provided for under the national legislation in this area.’82 This was drafted in terms that, as academic commentary had suggested, granted such wide latitude to Member States as to rule out direct effect.83 The choice of the verb ‘may’ over an imperative form such as ‘shall’ or ‘will’ should not be overlooked, for it was surely the result of careful consideration at the drafting stage. Not surprisingly, Germany and Austria argued that this wording imposed no obligation, but the Commission asserted otherwise and crucially so held the Court. Non-discriminatory access to courses including those provided abroad, as in Gürol itself, would, it was held, be purely illusory if Turkish children were not assured of an equal right to the relevant grant. This was considered the only interpretation making it possible to attain in full the objective pursued by Article 9 of guaranteeing equal opportunities for Turkish children and those of host State nationals in education and vocational training. But asserting that this is the objective of the provision does not make it so. If that were, indeed, the objective, as contrasted with ensuring equal treatment with respect to entry qualifications, then the expressed intention of the parties could have reflected this directly rather than, as they did, expressly opting not to use imperative language.84 It is no solution for the Court to assert that, like the first sentence, it lays down an obligation of equal treatment when the language chosen is not unconditional. The general rule of treaty interpretation, codified in the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (Art 31) is that a treaty is to be interpreted in good faith in accordance with the ordinary meaning to be given to its terms in their context and in light of its object and purpose. A term should be given its ordinary meaning since it is reasonable to assume that until the contrary is established this is most likely to reflect what the parties intended.85 And it would be unpersuasive to suggest that in Guürol the contrary was convincingly established. Austria and Germany were not alone in their ordinary meaning interpretation, for at least one other Member State has changed its law in the wake of the ruling.86

2.1.2.2 Social security provisions

The seminal Kziber judgment is the fountain from which nearly all later jurisprudential developments pertaining to social security provisions in EU Trade Agreements have stemmed.87