Cell Phones

Introduction

The cellular service market is an economically significant market that has substantially enhanced consumer welfare. From 1990 to 2009, the U.S. market grew from 5 million subscribers to 291 million subscribers. At the time of this writing, 93 percent of Americans have a cell phone, and an increasing number of households have given up their landlines and rely entirely on wireless communications. Annual revenues of the four national carriers—AT&T, Verizon, Sprint, and T-Mobile—total over $180 billion.

While acknowledging these successes and welfare benefits, the focus of this chapter is on the failures of this market. We’ll see how carriers design their contracts in response to the systemic mistakes and misperceptions of their customers. In doing so, they impose welfare costs on consumers, reducing the net benefit that consumers derive from wireless service. We’ll focus on three design features common to most cellular service contracts:

• three-part tariffs;

• lock-in clauses; and

• sheer complexity.

As you have no doubt noticed, a major theme of this book is that the interaction between consumer psychology and market forces results in contracts that feature complexity and deferred costs. Lock-in clauses and three-part tariffs together generate cost deferral. Lock-in clauses enable bundling of handsets and cellular service. This bundling allows carriers to offer free or subsidized phones—an upfront benefit—recouping costs at the back end through the price of cellular service. This cost deferral is motivated by consumers’ demand for short-term perks and their relative inattentiveness to long-term costs. The underestimation of long-term costs is amplified by the three-part tariff, which responds to and exacerbates the effect of misperceptions that lead consumers to underestimate the cost of cellular service. Sheer complexity is the third of the three design features that contribute to market failure.

A. Three Design Features

The basic pricing scheme of the common cellular service contract is a three-part tariff comprising (1) a monthly charge, (2) a number of voice minutes that the monthly charge pays for, and (3) a per-minute price for minutes beyond the plan limit. The three-part tariff is a rational response by sophisticated carriers to consumers’ misperceptions about their cell phone usage. Consumers choose calling plans based on a forecast of future use patterns. The problem is that many consumers do not have a very good sense of these use patterns—some underestimate whereas others overestimate their future usage. The three-part tariff is advantageous to carriers because it exacerbates the effects of consumer misperception, leading consumers to underestimate the cost of cellular service.

The overage-fee component of the three-part tariff targets the underestimators. These consumers underestimate the probability of exceeding the plan limit and incurring an overage fee. As a result, they underestimate the total cost of the cellular service. The other components of the three-part tariff, the monthly charge and the fixed number of minutes that come with it, target the over-estimators. These consumers think that they will use most or all of their allotted minutes. They therefore expect to pay a per-minute price equal to the monthly charge divided by the number of allotted minutes. In fact, the over-estimators use far fewer minutes and end up paying a much higher per-minute price. In this way, then, over-estimators also underestimate the cost of cellular service.

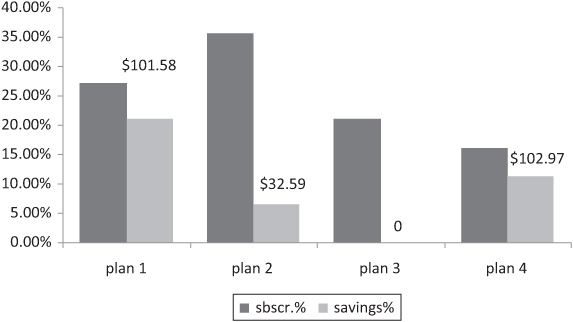

Carriers seem to be aware of these misperceptions. As a pricing manager a top U.S. cellular phone carrier explained, “people absolutely think they know how much they will use and it’s pretty surprising how wrong they are.”1 The prevalence of consumer misperception can be empirically confirmed by using a unique dataset of subscriber-level monthly billing and usage information for 3,730 subscribers at a single wireless provider. These data enable calculation of not only the total cost of wireless service under each consumer’s chosen plan, but also the total amount that the consumer would have paid had he chosen other available plans. Thus, one can determine the plan that best fits actual cell phone usage. The data show that over 65 percent of consumers chose the wrong plan. Some chose plans with an insufficient number of allotted minutes, whereas others chose plans with an excessive number of allotted minutes. Subscribers exceeded their minute allowance 17 percent of the time by an average of 33 percent, suggesting underestimation of use. And, during the 81 percent of the time when the allowance was not exceeded, subscribers used only 47 percent of their minute allowance on average, suggesting overestimation.

In addition to the three-part tariff pricing structure, most calling plans come with a free or substantially discounted phone and a long-term contract with an early termination fee (ETF) that effectively locks the consumer in for a substantial time period—typically two years. These lock-in clauses and the accompanying ETFs can also be explained as a market response to the imperfect rationality of consumers. Imperfectly rational consumers underestimate the cost of lock-in, since they underestimate the likelihood that switching providers will be beneficial down the road. Switching providers may be beneficial, for example, if current service is not as good as promised, monthly charges are higher than expected (due to the misperception of use levels discussed above), or another carrier is offering a better deal.

The lock-in that is enforced by the ETF also facilitates the common practice of bundling phones and service. The long-term revenue stream that lock-in guarantees enables carriers to offer free or subsidized phones. Rational consumers, knowing that they will pay for this “free” phone in the long term, would not be enticed by a free-phone offer. Imperfectly rational consumers, on the other hand, discount the long-term cost and seek out “free” phone offers.

Finally, the third design feature that contributes to the behavioral market failure is the sheer complexity of the cell phone contracts. Cellular service contracts are complex and multidimensional. Choosing among numerous contracts can be a daunting task. The three-part tariff itself is complex. Lock-in clauses and ETFs add further complexity. In addition, the true cost of a calling plan depends on numerous other features. For example, most plans offer unlimited night and weekend calling, but carriers offer different definitions of “night” and “weekend.” Also, consumers must choose between unlimited in-network calling, unlimited calling to five numbers, unlimited Walkie-Talkie, rollover minutes, and more. Finally, different carriers offer different ranges of handsets, handset subsidies vary, and so on. Complexity is further increased when family plans are added to the mix, data services are added to voice services, prepaid plans are considered in addition to postpaid plans, and so forth. According to one industry estimate, the cellular service market boasts over 10 million plan and add-on combinations.

This level of complexity can itself be viewed as a contractual design feature that responds to the imperfect rationality of consumers. Complexity allows providers to hide the true cost of the contract. Imperfectly rational consumers do not effectively aggregate the costs associated with the different options and prices in a cell phone contract. Inevitably, consumers will focus on a subset of salient features and prices, and ignore or underestimate the importance of the remaining non-salient features and prices. In response, providers will increase prices or reduce the quality of the non-salient features. This, in turn, will generate or free up resources for intensified competition on the salient features. Competition forces providers to make the salient features attractive and the salient prices low. This can be achieved by adding revenue-generating, non-salient features and prices. The result is an endogenously derived high level of complexity and multidimensionality. Interestingly, consumer learning can exacerbate the problem. When consumers learn the importance of a previously non-salient feature, carriers have a strong incentive to come up with a new one, further increasing the level of complexity.

B. Rational-Choice Explanations?

Before we can draw normative and prescriptive implications from these behavioral theories, we must consider whether the more traditional rational-choice model can explain the same design features. If the rational-choice model comes up short, then we have good reason to appeal to behavioral economics to assess the appropriate policy response.

The leading rational-choice explanation for three-part tariffs views these tariffs as mechanisms for price discrimination or market screening among rational consumers with different ex ante demand characteristics. The price-discrimination argument rests on specific assumptions about the distribution of consumer types—assumptions that are not borne out in the cell phone market. With the distribution of types that we actually observe, providers selling to rational consumers would not offer three-part tariffs.

Lock-in clauses can arise when consumers are rational. This happens when sellers incur substantial per-consumer fixed costs and liquidity-constrained consumers cannot afford to pay upfront fees equal to these fixed costs. However, in the cell phone market, while fixed costs are high, they are also endogenous. Carriers invest up to $400 in acquiring each new customer, but much of these customer-acquisition costs are attributed to the free or subsidized phones that carriers offer. This raises a series of questions. Why do carriers offer free phones and lock-in contracts? Why not charge customers the full price of the phone to avoid the lock-in? How many consumers cannot afford to pay for a phone up-front? For how many of these liquidity-constrained consumers is the carrier the most efficient source of credit? The rational-choice model can explain the presence of lock-in clauses, but only in a subset of contracts.

The rational-choice explanation for complexity is straightforward: Consumers have heterogeneous preferences, and the complexity and multidimensionality of the cellular service offerings cater to these heterogeneous preferences. But while this heterogeneity likely explains some of the observed complexity in the cell phone market, it cannot fully account for the staggering level of complexity exhibited by the long menus of multidimensional contracts available to consumers. Even for the rational consumer, acquiring and comparing information on the range of complex products is a time-consuming and costly undertaking. At some point, the costs exceed the benefit of finding the perfect plan. Comparison-shopping is deterred, and the benefits of the variety and multidimensionality are left unrealized. It seems that in the cell phone market, the optimal level of complexity has been exceeded.

C. Welfare Costs

The design of cellular service contracts is best explained as a rational response to the imperfect rationality of consumers. Consumer mistakes and providers’ responses to these mistakes hurt consumers and generate welfare costs. For example, consumers who misperceive their future use patterns choose the wrong three-part tariff; that is, they do not choose the plan that would minimize their total costs. Extrapolating from the sample of 3,730 subscribers described above, the total annual reduction in consumer surplus from the three-part tariff structure exceeds $13.35 billion. Moreover, while the average annual harm per consumer, $47.68, is small, this average masks potentially important distributional implications. The $13.35 billion harm is not evenly divided among the 250 million U.S. cell phone owners. Many of these subscribers choose the right plan. Even among those who choose the wrong plan, there is substantial heterogeneity in the magnitude of their mistakes. Each year, 42.5 million consumers make mistakes that cost them at least 20 percent of their total yearly wireless bill, or $146 per consumer annually. The distribution of mistakes implies a potentially troubling form of regressive redistribution, since revenues from consumers who make mistakes keep prices low for consumers who do not make mistakes.

Other welfare costs are a consequence of lock-in. Lock-in prevents efficient switching and thus hurts consumers. Switching is efficient when a different carrier or plan provides a better fit for the consumer. One survey found that while 47 percent of subscribers would like to switch plans, only 3 percent do so. The rest are deterred by the ETFs. Lock-in can also slow the beneficial effects of consumer learning and prolong the costs of consumer mistakes, since even consumers who learn from experience cannot benefit from their new-found knowledge by immediately switching to another carrier’s plan. (Insofar as carriers allow consumers to switch among their own monthly plans, consumers can benefit from learning.) In addition to these direct costs, lock-in may inhibit competition, adding a potentially large indirect welfare cost. Since lock-in may prevent a more efficient carrier from attracting consumers who are locked into a contract with a less efficient carrier, it can deter new carriers from entering the market.2

Complexity is another detriment to welfare. The high level of complexity of cell phone contracts can reduce welfare in two ways. First, consumers tend to make more mistakes in plan choice when the menus are complex, and these mistakes reduce consumer welfare. Second, complexity inhibits competition by discouraging comparison-shopping. By raising the cost of comparison-shopping, complex contracts reduce the likelihood that a consumer will find it beneficial to carefully consider all available options. Without the discipline that comparison-shopping enforces, cellular service providers can behave like quasi-monopolists, raising prices and reducing consumer surplus.

D. Market Solutions and Their Limits

Do these behavioral market failures result from imperfect competition in the cell phone market? The simple answer is “no.” In fact, enhanced competition would likely make the identified design features more pervasive and the resulting welfare costs higher. If consumers misperceive their future use levels, competition will force carriers to offer three-part tariffs. If consumers are myopic, competition will force carriers to offer free phones and cover the cost of the subsidy with lock-in contracts. Finally, if consumers ignore less salient price dimensions of complex, multidimensional contracts, competition will force carriers to shift costs to these less salient price dimensions. When demand for cellular service is driven by imperfect rationality, competitors must respond to this biased demand; otherwise, they will lose business and be forced out of the market. Accordingly, given consumers’ imperfect rationality, ensuring robust competition in the cellular service market would not in itself solve the problem.

But it is a mistake to take the level of imperfect rationality as given. As we have seen in previous chapters, competition, coupled with consumer learning, can reduce levels of bias and misperception and thus trigger a shift to more efficient contractual design. In fact, the cellular service market has exhibited numerous examples of such market correction in recent years and now boasts a large set of products and contracts that cater to more sophisticated consumers.

At the same time, however, the evolution of the market demonstrates limits on the power of consumer learning to correct behavioral market failures. For example, the market has responded to greater consumer awareness of the costs of underestimated use among consumers who have experienced the sting of large overage charges. Since 2008, the major carriers have been offering unlimited calling plans that arguably respond to demand generated by this heightened consumer awareness. Yet, while overage fees make it easy to learn the cost of underestimated use, the costs of overestimated use are more difficult to learn since they are not so obviously penalized. The result of this uneven learning is unlimited plans rather than the optimal two-part tariff pricing scheme comprised of a fixed monthly fee and a constant per-minute charge.

Innovations like these suggest that the market has an impressive capacity to correct for consumer misperceptions. Yet, market solutions are imperfect. Not all biases are easily purged by learning. Not all consumers learn equally fast, as evidenced by the limited adoption of many design innovations. The speed of consumer learning and the market’s response matter, since welfare costs are incurred in the interim period. Moreover, when consumers learn to overcome one mistake, or when a previously hidden term becomes salient, carriers have an incentive to trigger a new kind of mistake or to add a new non-salient term. Even if consumers always catch up eventually, this cat-and-mouse game imposes welfare costs on consumers.

E. Policy Implications

While market solutions are imperfect and welfare costs remain, the potential for self-correction in the cellular service market merits a regulatory stance that facilitates rather than impedes market forces; disclosure regulation. The proposal we’ll explore deviates from existing disclosure regulation and from most other proposals for heightened disclosure regulation. Current disclosure regulation and other proposals focus on the disclosure of product-attribute information; namely, information on the different features and price dimensions of cellular service. The proposal we’ll explore, by contrast, emphasizes the disclosure of use-pattern information, which as you’ll recall from earlier chapters is information on how the consumer will use the product. To fully appreciate the benefits and costs of a cellular service contract, consumers must combine product-attribute information with use-pattern information. For example, to assess the costs of overage fees, it is not enough to know the per-minute charges for minutes not included in the plan, as proposed in the Cell Phone User Bill of Rights. Consumers must also know the probability that they will exceed the plan limit and by how much. Use-pattern information can be as important as product-attribute information. The disclosure regime should be redesigned to ensure that consumers have access to both.

There are two possible approaches to disclosure regulation, approaches that are not mutually exclusive. The first approach focuses on designing simple disclosures that can be easily understood and utilized by imperfectly rational consumers. In particular, carriers should provide total-cost-of-ownership (TCO) information, which is the total amount paid by the consumer, given the consumer’s specific use patterns. This information should be provided as an annual disclosure, such as on the year-end summary, to account for month-to-month variations in use. The TCO disclosure combines product-attribute information (pricing information) with information on the specific consumer’s use patterns. This disclosure could be further supplemented by information on alternative service plans that would reduce the total price paid by consumers given their current use patterns.

The second approach to disclosure regulation re-conceptualizes disclosure, targeting the disclosed information not directly at consumers but rather at sophisticated intermediaries. Under this approach, carriers would provide comprehensive, individualized use information in electronic, database form. Imperfectly rational consumers will not try to analyze this information on their own. Instead, they will forward the information to sophisticated intermediaries. By combining the use information with the attribute information they collect on product offerings across the cell phone market, the intermediaries would be able to help each consumer find the plan that best suits his or her specific use patterns.

The remainder of this chapter is organized as follows:

• Part I provides background information on the cell phone and the cellular service market.

• Part II describes the key features of common cellular service contracts.

• Part III develops the behavioral-economics theory that explains these contractual design features, after concluding that rational-choice explanations fall short.

• Part IV discusses welfare implications.

• Part V considers the efficacy of market solutions.

• Part VI turns to policy, offering guidelines for enhanced disclosure regulation.

I. The Cell Phone and the Cellular Service Market

A. The Rise of the Cell Phone

1. Technology

The key technological innovation that underpins cellular communications is the cellular concept itself. A cellular system divides each geographic market into numerous small cells, each of which is served by a single, low-powered transmitter. This allows the system to reuse the same channel or frequency in non-adjacent cells in order to avoid interference. Thus, multiple users can simultaneously make use of the same frequency. Sophisticated technology locates subscribers and sends incoming calls to the appropriate cell sites, while complex handoff technologies allow mobile consumers to move seamlessly between cells.3

High demand for cellular service has prompted the development of digital technology, which generates enhanced capacity without degrading service quality. Two kinds of capacity-increasing technological solutions have emerged. The first employs time-slicing technology; signals associated with several different calls are aggregated within the same frequency by assigning to each user a cyclically repeating time slot in which only that user is allowed to transmit or receive. Time-slicing techniques include Bell Labs’ time division multiple access (TDMA) and Global System for Mobile (GSM), which are used by AT&T and T-Mobile, and Integrated Digital Enhanced Network (iDEN), which is used by Nextel. Spread spectrum techniques, by contrast, spread many calls over many different frequencies while using highly sophisticated devices to identify which signals belong to which calls and decode them for end users. The family of digital standards employing spread spectrum technology is known as Code Division Multiple Access (CDMA). CDMA standards are used by Verizon and Sprint. The introduction of these digital cellular technologies, starting in the early 1990s, marked the advance from first-generation (1G) systems to second-generation (2G) systems. Third-generation (3G) systems, which began to operate in the U.S. in 2002, incorporate more advanced technologies that provide the increased speed and capacity necessary for multimedia, data, and video transmission, in addition to voice communications. And now fourth-generation (4G) systems are being deployed.

2. History

Although the key concepts essential to modern cellular systems were conceived in 1947, the Federal Communications Commission’s (FCC) refusal to allocate substantial frequencies to mobile radio service meant that significant development of cellular telephone services was delayed for several decades. It was not until the early 1980s that the FCC allocated 50 MHz of spectrum in the 800 MHz band to cellular telephone service. The FCC rules created a duopoly of two competing cellular systems in each of 734 “cellular market areas”—one owned by a non-wireline company and one owned by the local wireline monopolist in the area. Each carrier received 25 MHz of spectrum. The first set of cellular licenses, which pertained to the thirty largest urban markets (the Metropolitan Service Areas or MSAs) were allocated by comparative hearings. However, the FCC was so overwhelmed by the number of applicants that in 1984 Congress authorized the use of a lottery system to allocate spectrum in the remaining markets. By 1986, all the MSA licenses had been allocated, and by 1991 licenses had been allocated in all markets. As demand for cellular service rapidly increased over subsequent years, the FCC allocated more spectrum to wireless communications. New spectrum has been allocated by auction rather than lottery ever since Congress gave the FCC authority to issue licenses through auctions in the 1993 Budget Act, a move designed to raise revenues and cut down on delays associated with the lottery system.4

The more recent history of the cellular service market in the U.S. is one of consolidation. As noted above, the industry began with the local structural duopolies that were created by the FCC’s lottery mechanism. With different firms operating in different geographical markets, the national market initially included a large number of players. The number of firms increased further as the FCC auctioned off more and more radio spectrum for cell phone use. But this high level of market dispersion did not last long. The FCC placed few restrictions on the ability of firms to merge across markets, and a long history of voluntary merger and acquisition activity followed. Soon a handful of firms—AT&T Wireless, Cingular, Nextel, Sprint, T-Mobile, and Verizon Wireless—gained a dominant position as nationwide carriers. Consolidation activity increased in 1999, as national carriers sought to fill in gaps in their coverage areas and increase the capacity of their networks while regional carriers sought to enhance their ability to compete with the nationwide operators. Consolidation was further facilitated by the FCC’s 2003 decision to abolish the regulatory spectrum cap that had limited the amount of spectrum that a company could own in any one geographical market, since this opened the door to mergers by companies with overlapping coverage areas. Most significantly, in October 2004, Cingular and AT&T Wireless merged to become AT&T Wireless, while in December 2004 Sprint and Nextel merged to become Sprint Nextel.5

3. Economic Significance

The FCC estimates that at the end of 2009, there were 291 million cellular service subscribers in the U.S., which corresponds to a nationwide penetration rate of 93 percent. The market has been growing rapidly, albeit with signs that the market is approaching saturation. Cellular service providers added 11.1 million new subscribers in 2009, 16.6 million in 2008, 21.2 million in 2007, 28.8 million in 2006, 28.3 million in 2005, 24.1 million in 2004, and 18.8 million in 2003. An historical perspective underscores the stellar growth of the market; 286 million subscribers were added between June 1990 and the end of 2009. While cell phones complement landline phones for most users, a significant and increasing number of users view the cell phone as a partial or even complete replacement for the traditional, landline phone. In the first half of 2010, an estimated 26.6 percent of households used only wireless phones, up from 4.2 percent at the end of 2003.6

The high revenues enjoyed by carriers provide an indication of the magnitude of the cellular service market. In the second quarter of 2011, Verizon posted wireless revenues of $17.3 billion, AT&T $15.6 billion, Sprint $7.5 billion, and T-Mobile $5.1 billion.7 Total quarterly wireless revenues for the four national carriers were $45.5 billion, which potentially translates into total annual wireless revenues of $182 billion, ignoring seasonal variations. Wireless telecommunications have become the largest source of profit for nearly all major telecommunication providers. For example, Verizon’s wireless services are about twice as profitable as its wireline offerings.8 Looking at revenues from spectrum auctions is also instructive. In 2006, the FCC’s Auction No. 66 raised a total of $13.7 billion in net bids from wireless providers for 1,087 spectrum licenses in the 1710–1755 MHz and 2110–2155 MHz bands.9 In 2008, the FCC’s Auction No. 73 raised a total of $19.0 billion in net bids from wireless providers for 1,099 licenses in the 698–806 MHz band (known as the “700 MHz Band”).10

Investment in telecommunications infrastructure in general—and one could argue cellular technology in particular—promotes economic growth by reducing the costs of interaction, expanding market boundaries, and enhancing information flow. Specifically, cellular technology can create value by facilitating communication between individuals who are on the move, thus helping individuals to better coordinate their activities and respond to unforeseen contingencies. Wireless services also boost growth by expanding telephone networks to include previously disenfranchised consumers through prepaid service that is unavailable for fixed lines. Analysts estimate that the decades-long delay in the development of cellular networks after the discovery of the cellular concept cost the U.S. economy around $86 billion (measured in 1990 dollars).11

B. The Cellular Service Market

1. Structure

The U.S. cellular service industry is dominated by four “nationwide” facilities-based carriers: AT&T Wireless, Verizon Wireless, Sprint Nextel, and T-Mobile. At the end of 2010, each had networks covering at least 250 million people. AT&T had 95.5 million subscribers, Verizon 94.1 million, Sprint Nextel 49.9 million, and T-Mobile 33.7 million.12

In addition to the national carriers, there are a number of regional carriers, including Leap, U.S. Cellular, and MetroPCS. There is also a growing resale sector, consisting of providers who purchase airtime from facilities-based carriers and resell service to the public, typically in the form of prepaid plans rather than standard monthly tariffs.

2. Competition

The overlapping geographic coverage of the national and regional providers gives rise to competition between cellular service providers. The FCC estimates that 97.2 percent of people have three or more different operators offering cell phone services in the census blocks where they live, 94.3 percent live in census blocks with four or more operators, 89.6 percent live in census blocks with five or more operators, 76.4 percent live in census blocks with six or more operators, and 27.1 percent live in census blocks with seven or more operators. The FCC measures market concentration by computing the average Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) across 172 Economic Areas (EAs)—aggregations of counties that have been designed to capture the “area in which the average person shops for and purchases a mobile phone, most of the time.” The HHI is a measure of market concentration that ranges from a value of 10,000 in a monopolistic market to zero in a perfectly competitive market.13 In mid-2010, the average HHI, weighted by EA population, was equal to 2,848. An industry with an HHI above 2,500 is considered highly concentrated by the antitrust authorities. And these figures might well underestimate market concentration, since the FCC’s methodology gives equal weight to a mobile carrier assigning cell phone numbers in one county as it does to a carrier that assigns numbers in multiple counties in a given EA.14 Indeed, one analyst calculated an average HHI value exceeding 6,000 with 2005 data, using the amount of spectrum controlled by a carrier in a market as a proxy for market share.15

The relatively high level of concentration in the cell phone market is the product of an ongoing consolidation process. This consolidation is at least partly motivated by a desire to realize economies of scale and enlarge geographic scope. Broad coverage can be provided at lower cost by a single nationwide carrier than by regional carriers through roaming agreements with carriers operating in different geographic areas. In addition, extending the national network spreads fixed costs, such as marketing expenditures and investments in developing new technology, over a wider base of customers. Economies of geographic scope arising from complementarities between markets may also provide an efficiency reason for consolidation.16 However, even if consolidation reduces certain costs, other costs may increase. Consolidation tends to reduce competition and facilitate collusion as the number of multi-market contacts between the dominant national carriers increases.17

The magnitude of entry barriers provides another important measure of competitiveness. If entry barriers are low, even a market with a small number of firms will behave competitively. Government control of spectrum—limiting the amount of spectrum allocated to wireless communications and requiring carriers to obtain a government-issued license—has the potential to create significant barriers to entry. However, the FCC has alleviated many of these concerns recently by increasing the amount of spectrum available for cellular communication services and allowing market forces to determine market structure through elimination of the old structural duopolies and abolition of the spectrum cap. Moreover, the Telecommunications Act and FCC regulations reduce entry barriers by imposing interconnection and roaming obligations. The ability to purchase spectrum on the secondary market further reduces entry barriers.18 Meanwhile, advertising expenditures—amounting to billions of dollars annually19—and the economies of scale and scope described above continue to impose substantial entry barriers.

Switching costs also affect the level of competition. Switching costs in the cellular service market are substantial, although recent developments are reducing these costs. Until recently, most consumers signed long-term contracts with fixed ETFs of approximately $200. But now major carriers are offering contracts with graduated ETFs that decline over the life of the contract. Likewise, historically carriers have allowed only certain approved phones to be used by their subscribers on their network and “locked” the phones they sold to render them incapable of being used on other networks.20 The recent trend, however, is toward open access, which allows more phones onto the network, and recent regulatory action by the Copyright Office clarified that phones can be unlocked.21 Being forced to change phone numbers was also a potentially significant switching cost until it was eliminated by the regulatory requirement that carriers provide local number portability.22 The high churn rates in the cell phone market—between 1.5 percent and 3.3 percent per month in 200923—suggest that switching costs, while potentially substantial, are not prohibitive for many consumers.

To sum up, while there is reason to believe that the cellular service market is less than perfectly competitive, cellular service providers are actively competing to attract consumers. Declining prices, albeit with a leveling off in recent years, are evidence of such active competition.24 Competition is also observed on non-price dimensions. Competition to attract and retain customers appears to be driving carriers to improve service quality. Carriers pursue a variety of strategies to improve service quality, including network investment to improve coverage and quality and acquisition of additional spectrum.25 While an economic conclusion reached by politically appointed regulators should be taken with a grain of salt, it is noteworthy that the FCC described the cellular service market as one characterized by healthy competition with carriers engaging in “independent pricing behavior, in the form of continued experimentation with varying pricing levels and structures, for varying service packages, with various handsets and policies on handset pricing.”26

3. Related Markets

The cellular service market interacts with other markets, specifically with the market for phones/handsets and with the market for cell phone applications.

a. The Handset Market

The market for handsets is controlled by five firms: Samsung, LG Electronics, Motorola, Apple, and RIM. In the U.S., Samsung enjoys the largest market share, controlling 25.5 percent of the handset market in the second quarter of 2011. LG placed second with 20.9 percent of the market, and Motorola followed with 14.1 percent. Apple and RIM, the maker of BlackBerry, lag behind considerably with 9.5 percent and 7.6 percent of the market, respectively.27

In the U.S., the major cellular service providers exert significant control over the handset market. Internationally, about half of handsets are purchased through carriers and about half are sold directly to consumers through other channels. In the U.S., the vast majority of cell phones—nine out of every ten phones according to one estimate—are sold through a service provider.28 The practice of subsidizing handset prices for consumers who sign long-term service contracts is at least partially responsible for the competitive disadvantage suffered by handset makers looking to sell directly to consumers.

Carriers in the U.S. determine which devices consumers can operate on their networks. The result of this control by service providers is that only a fraction of any given manufacturer’s total line of products is offered. For example, in 2006, of the fifty new products Nokia introduced into the market, U.S. cellular service providers offered a scant few. By allowing only certain approved phones on their networks, carriers influence the design of handsets. Moreover, as a condition of network access, carriers require that developers disable certain services or features that might be useful to consumers, such as call-timers, photo sharing, Bluetooth capabilities, and Wi-Fi capabilities.29

But the balance of power is shifting. Handset brands and models are an increasingly important determinant of a consumer’s choice of service provider. Apple’s launch of the iPhone is a significant example of a handset manufacturer successfully overcoming carrier pressure. More generally, the rapid expansion of the “smartphone” market is enhancing the power of handset makers and companies who provide software for these handsets. An example is the Android operating system, developed by Google.30

In addition, the open-access trend is starting to limit carriers’ control over the handset market.31 Regulation is also playing an important role: One-third of the recently auctioned spectrum comes with a requirement that “cellular networks allow customers to use any phone they want on whatever network they prefer, and be able to run on it any software they want.”32 And, perhaps sensing the inevitable, carriers are beginning to embrace the new open-access business model, reasoning that they can cut costs by eliminating handset subsidies and letting handset manufacturers bear most of the development and customer service costs.33

b. The Applications Market

The major cellular service providers and other mobile data providers have progressively introduced a wide variety of mobile data services and applications, including text and multimedia messaging, ringtones, GPS navigation, and entertainment applications from games to TV and music players.34 Data revenues have been growing—in absolute numbers and as a share of total revenues. In 2009, $42 billion or 27 percent of total wireless service revenues were from data revenues.35

The major carriers exert substantial control over the applications market. Many applications—popularly known as “apps”—are often sold by the carriers as part of the service package. Although some application developers sell their applications directly to consumers, carriers exert considerable influence over the design, content, and pricing of cell phone applications. For example, carriers impose limits on “unlimited use” pricing plans for 3G broadband data services by restricting bandwidth and designating certain applications as “forbidden” in consumer contracts. Carriers also create obstacles for application developers by restricting access to many phone capabilities, imposing extensive qualification and approval requirements before allowing them to develop applications for their cell phone platforms, and by failing to develop uniform standards.36

As sophisticated new applications for cell phones have proliferated, however, handset manufacturers have started to put pressure on carriers to loosen their grip on the applications market. For example, the immense popularity of the iPod music player allowed Apple to persuade AT&T to sell the iPhone to its customers without also offering AT&T’s own line of applications.37

II. The Cellular Service Contract

Cellular service contracts are complex multidimensional contracts. This chapter does not attempt a comprehensive analysis of these contracts.38