Muslim Profiles Post-9/11: Is Racial Profiling an Effective Counter-terrorist Measure and Does It Violate the Right to be Free from Discrimination?

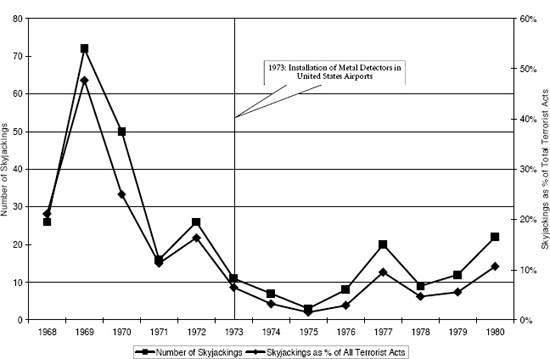

Figure 1. The Economic Model of Profiling

If the police are, in fact, searching more young Muslim men and getting to Time 3, where the offending rate of young Muslim men is lower than that of whites—1.3 versus 1.7 per 100 million—then the police must be bigoted: the only reason that a police officer would search more young Muslim men than at the Time 2 equilibrium—that is, would search, say, 80 per cent young Muslim men and 20 per cent whites, instead of the Time 2 distribution of 60/40—is if the officer had a taste for discrimination resulting in higher utility even though fewer young Muslim men are offending and thus fewer searches are successful.47

The three hypothetical distributions of searches between young Muslim men and all others—at Times 1, 2, and 3—correspond to three different sets of internal group search rates. These three scenarios also represent three different types of policing: colour-blind policing at Time 1 where the police take no account of race and therefore do not seek greater efficiency by targeting higher offenders; efficient police profiling at Time 2 where the police have sought to improve their hit rates by targeting higher offenders to the point of equilibrium; and excessive profiling or bigoted policing at Time 3 where the police are now searching more (beyond the point of efficiency) members of the lower-offending group. The three time points are represented in Figure 1.

The economic model represented by Figure 1 suggests that profiling increases the success rate of police investigations and reduces the overall societal level of offending with the same police resources. Naturally, additional judicial resources would be needed to process the increased detection of terrorist activities, although one expects that those costs would be offset by the harm that is prevented.

B. Elasticity among the Non-profiled and Possible Substitution Effects

Rational choice theory entails, however, that members of a profiled group are not the only ones who will respond to changes in policing. Members of the non-profiled group also change their behaviour as a result of the decreased cost of crime—but in their case, by increasing their offending. So, for instance, if the US taxing authorities target drywall contractors and car dealers for audits of their tax returns—as they did in the mid-1990s—we can expect that there will be less tax evasion by drywall contractors and car dealers because their cost of tax evasion has increased. But at the same time, we can expect that some, say, accountants and bankers will realise that they are less likely to be audited and may therefore cheat a bit more on their taxes. Similarly, if the highway patrol targets African-American motorists for stops and searches—again, there is evidence for this in several states in the United States—then we can expect African-American motorists to respond by offending less. But by the same token, white motorists may begin to offend more as they begin to feel increasingly immune from investigation and prosecution.

Similar substitution effects hold true in the terrorism context as well. It happened in Israel, for instance, when young girls and women started becoming suicide bombers. As Jonathan Tucker, a counter-terrorism expert has explained:

At first, suicide terrorists [in Israel] were all religious, militant young men recruited from Palestinian universities or mosques. In early 2002, however, the profile began to change as secular Palestinians, women, and even teenage girls volunteered for suicide missions. On March 29 2002, Ayat Akhars, an 18-year-old Palestinian girl from Bethlehem who looked European and spoke Hebrew, blew herself up in a West Jerusalem supermarket, killing two Israelis. Suicide bombers have also sought to foil profiling efforts by shaving their beards, dyeing their hair blond, and wearing Israeli uniforms or even the traditional clothing of orthodox Jews.48

In this sense, the opponents of racial profiling are also correct—and, also, as a matter of ‘statistical fact’. If we assume elasticity among rational actors, then profiling will increase offending among members of the non-profiled group. This has led many counter-terrorism experts to question or deny outright the effectiveness of profiling. As Bruce Hoffman has stated, ‘profiling of suicide bombers is no longer effective. Suicide attacks can be young or old, male or female, religious or secular’.49 It has led other counter-terrorism experts and practitioners, such as New York City Police Commissioner Raymond Kelly, to avoid profiling on traits that can substitute easily. As Malcolm Gladwell explains, ‘It doesn’t work to generalize about a relationship between a category and a trait when that relationship isn’t stable—or when the act of generalizing may itself change the basis of the generalization.’50 To avoid these ‘unstable’ traits, police chief Kelly does not rely on race but instead on traits like nervousness and inconsistency—traits that are more permanently associated with criminal offending and that do not lend themselves to substitution.

C. The Central Theoretical Puzzle

The fact that there may be elasticity and thus substitution among the non-profiled, however, does not end the debate about profiling. It does not mean that profiling is ineffective. Some substitution is inevitable. The real question is: how much substitution can we expect and will it outweigh the benefits of profiling? The central theoretical question is, in other words, how do the elasticities of the two groups compare? How does the elasticity of the profiled group compare to that of the non-profiled group?

The trouble with the economic model is that it assumes both groups are equally elastic to policing. This is reflected in the earlier graph by the parallel shape of the two offending curves. But this assumes away the central theoretical question. What matters most for the effectiveness of racial profiling is precisely the comparative elasticity of the two groups. If the targeted group members have lower elasticity of offending to policing—if their offending is less responsive to policing than other groups—then targeting them for enforcement efforts will increase the overall amount of crime in society because the increase in crime by members of the non-profiled group will exceed the decrease in crime by members of the profiled group. In raw numbers, the effect of the profiling will be greater on the more elastic non-profiled group and smaller on the less elastic profiled group.

Again, this is true as well in the terrorism context. The central question here is how responsive young Muslim men are to police profiling practices and whether they are less elastic than non-Muslim men and women. If they are less responsive overall, then targeted policing may actually increase total incidents of terrorism by encouraging the non-profiled group members to engage in terrorist acts—since the price to them has decreased. This would enable and encourage terrorist organisations to recruit more heavily from outside the profiled group—women, white men and others who do not look like young Muslim men.

It is precisely the comparative elasticities of offending to policing that determine whether and to what extent there is substitution between members of the profiled and non-profiled groups. This is the central puzzle, but at this theoretical level, there is no good reason to assume that the higher-offending group is as responsive or more responsive to policing than members of the non-profiled groups. After all, we are assuming that the two groups have different offending rates. Whether it is due to different socio-economic backgrounds, to religious fanaticism, to education, culture, or upbringing, non-spurious profiling rests on the non-spurious assumption that one group of individuals offends more than the other, holding everything else constant. If their offending is different, then why would their elasticity be the same? If members of the profiled group are offending more because they are more religious, then might they also be less elastic to policing? There is no a priori reason why the group that offends more should be more or as elastic than the other.

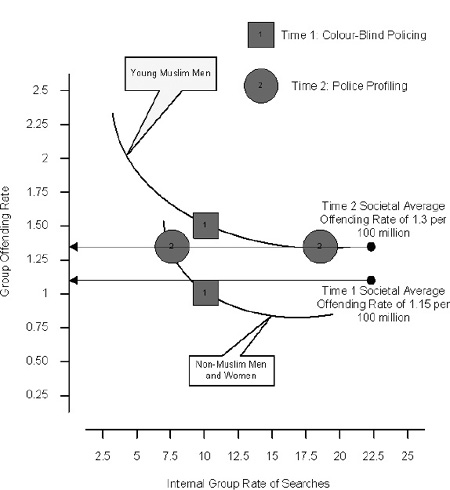

The bottom line, then, is that if the profiled group has lower elasticity of offending to policing, profiling that group will probably increase the amount of terrorism in the long-term. I have demonstrated this elsewhere with mathematical equations,51 but the proof is captured well and more simply by modifying the earlier graph to reflect different elasticities (see Figure 2). In essence, as long as the equilibrium point in offending at Time 2 is achieved above the average offending rate at Time 1, the profiling will produce increased crime in society.

In the terrorism context, the elasticity of offending represents only one form of possible substitution. There are other forms that can also result in an increased long-term rate of attacks, including, for instance, the use of different terrorist modes of attack that are less susceptible to detection by profiling. The central empirical issues, then, are: (1) whether and to what extent the group of profiled individuals (young, Arab-looking males) are elastic to policing; (2) whether and to what extent the group of non-profiled individuals (non-Arab-looking young men and all other men and women) are elastic to policing; (3) more importantly, how those elasticities compare; and (4) whether there are different forms of substitution that might also occur.

Figure 2. A Model of Profiling with Different Elasticities

E. Empirical Research on Counter-terrorism Measures

On these central questions, there is no reliable empirical evidence. There is no empirical research on elasticities, especially comparative elasticities, nor on substitution effects in the context of racial profiling.52 The only forms of substitution that have been studied empirically in the counter-terrorism context involve substitution as between different methods of attack and different timing of attacks.

Rigorous empirical research in the terrorism context traces its origins to a 1978 paper by William Landes that explores the effect of installing metal detectors in airports on the incidence of aircraft hijackings.53 Extending the rational choice framework to terrorist activities, Landes developed an economic model to test whether mandatory screening reduced the likelihood of a terrorist hijacking. Using a dataset of US FAA records of aircraft hijackings from 1961 to 1976, Landes analysed the time intervals between hijackings to measure the frequency of these events. Landes found that ‘increases in the probability of apprehension, the conditional probability of incarceration, and the sentence are associated with significant reductions in aircraft hijackings in the 1961-to-1976 time period’.54 He estimated that between 41 and 67 fewer aircraft hijackings occurred on planes departing from the United States following mandatory screening and the installation of metal detectors in US airports.55

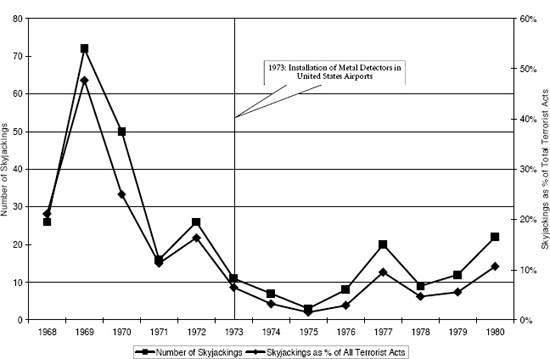

In his 1978 study, Landes used sophisticated quantitative analyses to regress the quarterly totals of aircraft hijackings, as well as time and flight intervals between successive hijackings, on the probability of apprehension. The effect, however, can be visualised here based on data from the RAND-MIPT Terrorism Incident Database Project.56 Figure 3 charts both the number of aircraft hijackings between 1968 and 1980, as well as the proportion of terrorist acts that consisted of hijackings.

The graph clearly demonstrates that mandatory screening and the installation of metal detectors in 1973 coincided with a significant drop in both the absolute number and the proportion of international terrorist acts represented by hijackings. Landes’ research suggests that terrorists’ decisions about whether to engage in terrorist acts are a function of the probability and expected utility of different possible outcomes.

Subsequent research has built on Landes’ framework to explore possible substitution effects. In a 1988 article, Jon Cauley and Eric Im used interrupted time series analysis to explore the impact of the installation of metal detectors on different types of terrorist attacks.57 They found that, although the implementation resulted in a permanent decrease in the number of hijackings, it produced a proportionally larger increase in other types of terrorist attacks.58 In 1993, Walter Enders and Todd Sandler also revisited mandatory screening, showing similarly that, although mandatory screening coincided with a sharp decrease in hijackings, it also coincided with increased assassinations and other kinds of hostage attacks, including barricade missions and kidnappings.59 The introduction of metal detectors, they showed, resulted in a steady increase in other kinds of hostage events—consistent with the idea that ‘terrorist groups substituted away from skyjackings and complementary events involving protected persons and into other kinds of hostage incidents’.60

Figure 3. US Aircraft Hijackings, 1968–80

Still other researchers have found that the implementation of counter-terrorism measures has had no impact on the risk of terrorism-related hijacking attempts. Laura Dugan, Gary LaFree and Alex R Piquero, in their 2005 article, ‘Testing A Rational Choice Model of Airline Hijackings’, have analysed a dataset that included 1,101 attempted aerial hijackings around the world from 1931 to 2003 and explored the effectiveness of a range of counter-terrorism measures—from the installation or metal detectors and tighter baggage and customer screening to increased law enforcement presence and punitive sanctions.61 When these researchers disaggregated their data into terrorist-related and non-terrorist related hijackings, they found that ‘none of the three policies examined were significantly related to the attempts or success of terrorist-related hijackings’.62 They concluded that ‘the counterhijacking policies examined had no impact on the hazard of terrorism-related hijacking attempts. By contrast, we found that metal detectors and increased police surveillance significantly reduced the hazard of nonterrorist-related hijackings.’63

Researchers have also looked at other forms of possible substitution. Retaliatory strikes, like the United States’ strike on Libya on 15 April 1986, resulted in ‘increased bombings and related incidents’;64 but they tended to level off later. As Enders and Sandler explain, ‘The evidence seems to be that retaliatory raids induce terrorists to intertemporally substitute attacks planned for the future into the present to protest the retaliation. Within a relatively few quarters, terrorist attacks resumed the same mean number of events.’65 Enders and Sandler also found that the fortification of US embassies and missions in October 1976 resulted in a reduction of terrorist attacks against US interests but produced a substitution towards assassinations.66 Cauley and Im also analysed the effect of target hardening of US embassies and found that they had an ‘abrupt but transitory influence on the number of barricade and hostage taking events’.67 Their conclusion was that ‘the unintended consequences of an antiterrorism policy may be far more costly than intended consequences, and must be anticipated’.68

However, that is the extent of the solid empirical evidence. The most recent and thorough review of the empirical literature, based on a Campbell Collaborative protocol, identified only seven rigorous empirical studies:

In the course of our review, we discovered that there is an almost complete absence of evaluation research on counter-terrorism strategies. From over 20,000 studies we located on terrorism, we found only seven which contained moderately rigorous evaluations of counter-terrorism programs. We conclude that there is little scientific knowledge about the effectiveness of most counter-terrorism interventions.69

Moreover, there are no empirical studies on racial profiling in the terrorism context. I found only one article, and it is theoretical, not empirical.70