Mainstreaming Wellbeing: An Impact Assessment for the Right to Health

Mainstreaming Wellbeing: An Impact Assessment for the Right to Health

The World Health Organization has written that ‘without health, other rights have little meaning’ (Jamar 1994). Over the past decade, the full ramifications of this statement have become clearer, as the health and human rights movement has endeavoured to establish conceptual and analytical bridges between the two disciplines of health and human rights, to create a field of discourse that goes to the very essence of human wellbeing.

That discourse now faces the challenge of evolving itself from the conceptual to the operational, so that the linkages between health and human rights are explicitly recognised and incorporated in decision-making processes. There is therefore a rising call for new methodologies that can advance this ongoing evolution. A right-to-health impact assessment has been suggested as one such methodology, on the basis that it might provide decision makers across sectors with an evidence-based mechanism for analysing and anticipating the effects of their decisions.

This chapter seeks to explore that possibility by examining the experiences of health impact assessment and human rights impact assessment and considering whether a right-to-health impact assessment offers anything more than these existing methodologies. These considerations belie complex conceptual and methodological issues, and the chapter offers some preliminary thoughts on the issues with which the health and human rights movement will need to grapple as it continues its struggle to mainstream human wellbeing.

Health as a Human Right

Written in 1946, the Constitution of the World Health Organization (WHO) contains in its preamble one of the most enduring statements of health as ‘a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being’ and its conception as a fundamental human right (Toebes 1999, 36). While this definition catapulted health into the human rights framework, there has been a degree of inconsistency in the articulation of the right to health and the more delimited right to the ‘highest attainable standard of health’ in the human rights documents that have emerged since that time (Leary 1994). Such inconsistency can be partly attributed to the lack of conceptual clarity that has been associated with the normative content and scope of the right to health. As one of the bundle of economic, social and cultural rights, it was long overlooked on the basis that it was too vague and predominantly aspirational (Alston and Quinn 1987, 159; Meier 2006, 733; Chapman 1998, 390). However, in more recent times, the health and human rights movement has sought to revolutionise the linkages between health and human rights, and to give much-needed substance to the right to health as enshrined in international human rights law (Mann 1994; Gruskin and Tarantola 2005).

Through this process, there is now an understanding that the right to health is an inclusive one, and is inextricably related to and dependent on the realisation of other rights, which are also essential determinants of human wellbeing (CESCR 2000, para 3; Toebes 2001, 175). There is also a growing consensus that, notwithstanding the qualifying principles of progressive realisation and resource availability, the right to health has a core content that imposes immediate obligations upon states. That core content mandates state adherence to the fundamental principles of non-discrimination and participation (CESCR 2000, paras 11, 18 and 19) and compels states to provide minimum essential levels of primary health care, food, housing, sanitation and essential drugs, and to adopt and implement a national public health strategy (CESCR 2000, para 43). At the same time, the interrelated and essential elements of availability, accessibility, acceptability and quality provide a concrete standard against which state conduct can be measured (CESCR 2000, para 12; Toebes 2001, 177; Asher 2004, 37).

The right to health has therefore been invested with a substantive meaning that is capable of being operationalised. Such an evolution, from conceptual to operational, is essential if the right to health is to move beyond a slogan to something that has meaningful and useful application in the real world. This task presents a series of significant challenges, and the United Nations Special Rapporteur for Health has articulated the need for new techniques that are capable of engaging with relevant players, including policy makers and health practitioners, so as to mainstream the right to health (Hunt 2007a, paras 9 and 26; Farmer and Gastineau 2002, 663; Roth 2004). Impact assessment, particularly a right-to-health impact assessment, has been suggested as one such technique (Hunt 2007b, para 44; Gruskin et al. 2007, 453).

Health Impact Assessment

The past decade has seen the emergence of health impact assessment (HIA), which has been defined as:

… a combination of procedures, methods and tools by which a policy, program or project may be judged as to its potential effects on the health of a population, and the distribution of those effects within the population.

(ECHP 1999)

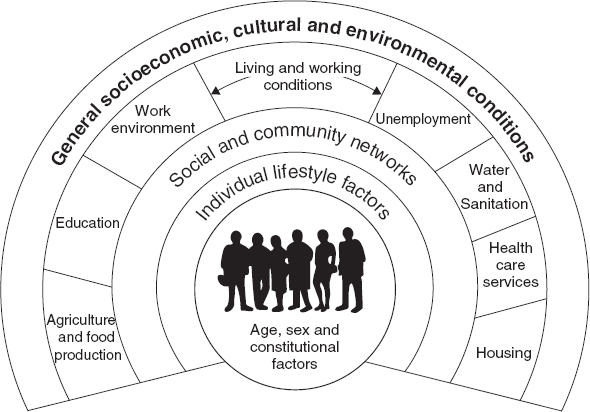

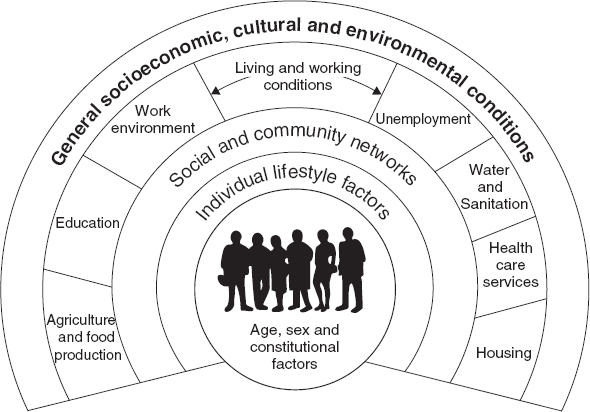

While HIA traces its origins to earlier methodologies of impact assessment, such as environmental impact assessment and social impact assessment, it also owes much of its existence to public health practitioners who perceived the potential of HIA as a means of promoting ‘healthy public policy’ (Kemm and Parry 2004, 16; Mahoney and Durham 2002; Mittelmark 2000). Through the influence of these practitioners, HIA has embraced a broad definition of health and has developed a clear understanding that the wellbeing of people is dependent on a spectrum of factors (ECHP 1999). These determinants of health have been illustrated as layers of influence, as depicted in Figure 14.1 (Dahlgren and Whitehead 1991).

Figure 14.1 Layers of Infference

By adopting this multidimensional model of health, HIA recognises that most policies or programs, including those in non-health sectors, have the potential to impact significantly through these layers of influence (Lock 2006, 11). In doing so, HIA advocates for a multidisciplinary approach to health, so that the responsibility for health is necessarily expanded to a range of sectors that would not otherwise give explicit consideration to health-related issues.

At the same time, this model of health enables HIA to provide a practical means of assessing potential health impacts. The links between health outcomes and health determinants are complex and multifactorial, so that it is often impossible to identify clear causal relationships. HIA offers a mechanism for overcoming that complexity by considering impacts in terms of health determinants rather than health outcomes, and by examining those determinants as categories and subcategories which correspond to the layers of influence depicted in Figure 14.1 (Lock 2006, 11). An assessment of the likely impact of a proposal on the various categories of determinants then provides a basis for drawing conclusions as to anticipated effects on the health of a community (Birley 2002).

Another significant dimension of HIA is health equity, and its recognition that the impacts of a policy or program will rarely be uniform throughout a population. HIA is therefore concerned to identify both the potential impacts of a proposal on the health of a population and the distribution of those impacts within the population. To that end, HIA has developed its capacity to ascertain how a proposal will impact on different population groups, including whether it might compound the distribution of existing health inequalities or impose new health burdens on specific groups (Taylor et al., 2003; Harris-Roxas et al. 2004).

One of the key methodologies for identifying such health inequalities is the use of a participatory approach to HIA, which allows those most likely to be affected by an intervention to identify the anticipated impacts on their state of wellbeing (ECHP 1999; Douglas et al. 2001, 152; Elliot et al. 2004, 81). It also democratises both the process of HIA and the decisions that HIA seeks to influence, by emphasising community participation in a transparent process for the formulation, implementation and evaluation of policies that affect the community (Kemm 2005; ECHP 1999). In this way, the process of HIA becomes as important as its outcomes, as it provides an empowering and consensus-building experience for community participants (Taylor et al. 2003; Kemm 2005; Mahoney and Durham 2002; Mahoney and Potter 2005, 19; Gillis 1999; O’Mullane 2007).

As HIA enters its second decade of experience, while many of the underlying principles of HIA have gained general acceptance, HIA practitioners have identified that if HIA is to achieve its ultimate goal of promoting healthy public policy, a vital challenge will be its ability to become entrenched within the decision-making process (Kemm 2005; Banken 2003; Davenport et al. 2006). Assuming HIA is up to this challenge, HIA has the potential to facilitate an awareness and understanding of health and its determinants across policy spheres and, in doing so, to introduce the core values of equity and democracy into decision-making processes. Expressed in these terms, it is not difficult to recognise that in bringing health into the consciousness of decision makers, HIA is also emphasising many of the core values that underpin the right to health. However, the concept of health as a human right has received little explicit consideration within HIA methodologies. In terms of impact assessment, that discussion has been left to the relatively embryonic field of human rights impact assessment.

Human Rights Impact Assessment

Much of the activity around human rights impact assessment (HRIA) has been in the field of business and human rights, as a result of the recent calls for businesses to take active steps to avoid human rights violations within their spheres of influence. HRIA has been perceived as one means of operationalising this call to action, with a number of different HRIA tools being developed to assist businesses in assessing the human rights impacts of their activities.

For example, the International Business Leaders Forum and the International Finance Corporation (IBLF/IFC) have collaborated in developing a self-assessment tool for businesses (IBLF/IFC 2007; Ersmaker 2007). The tool emphasises consultation with stakeholders, and encompasses eight steps sequencing from knowledge building to impact assessment, to final monitoring and evaluation (IBLF/IFC 2007, 40). In its summary of the human rights issues that may require assessment, IBLF/IFC categorises rights by those of workers, communities and customers (IBLF/IFC 2007, Appendix 4). Within each of these categories, the right to health is addressed in terms of the entitlement of workers to protection from risks to their health and safety in the workplace; the right of communities to be protected from adverse impacts on their health and safety arising from a company’s operations; and the obligation on companies to ensure that their products are not detrimental to the health of customers.

The human rights concerns associated with corporate involvement in foreign investment projects have also prompted Rights and Democracy to propose the use of HRIA for such projects (Rights and Democracy 2005; 2007; Brodeur 2007). The methodology developed by Rights and Democracy is intended as a community-led impact assessment of existing investment projects, and has been the subject of five reported case studies (Rights and Democracy 2007, 35). With respect to the right to health, the results of the case studies usefully illustrate how dependent the outcome of the assessment process is on the substantive meaning given to the underlying right. While Rights and Democracy cites the WHO definition of health, the main focus of its right-to-health questions is the impact of a project on health care and health services, as assessed using the criteria of accessibility, availability, acceptability and quality (Rights and Democracy 2005, 53). As a result, the consideration given to the right to health in the reports of the case studies is limited and in two of the five case studies an impact on the right to health is not identified at all as a concern.

The Halifax Initiative Coalition has also proposed the use of HRIA to develop a rights-based approach to trade and finance (Halifax Initiative Coalition 2004). The Coalition has outlined an impact assessment process that applies a human rights framework to existing impact assessment methodologies, such that the values of accountability, participation, equity and sustainability are placed at the core of the assessment process (Halifax Initiative Coalition 2004, 17). This approach is intended to produce an integrated impact assessment that identifies potential cultural, economic, social, civil and political rights impacts of a proposed project (Halifax Initiative Coalition 2004, 14).

There has also been consideration given to the use of HRIA to inform government decision-making processes. One of the earliest proposals was expounded by Larry Gostin and Jonathan Mann, who envisaged the use of HRIA in the formulation and assessment of public health policies (Gostin and Mann 1994). Their proposed tool was designed to provide policy makers with a systematic approach to exploring the human rights dimensions of such policies, and to assist them in balancing the public health benefits of a policy against its human rights burdens on individuals. In doing so, the tool recognised that human rights and public health may have competing priorities, and required assessors to explore how those priorities could be counterpoised (Watchirs 2002, 723).

More recent HRIA activity has focused on the application of HRIA as a means of mainstreaming human rights in policies or programs with international application. For example, the Norwegian Agency for Development Corporation (NORAD) has developed a handbook aimed at integrating human rights into development programs (NORAD 2001), while the Netherlands Humanist Committee on Human Rights (HOM) has similarly proposed the application of HRIA to policy measures of the European Union with an external effect (Radstaake and Bronkhurst 2002). In an early case study undertaken by HOM, the criteria used to assess the right to health, such as mortality rates and access to health-care facilities, suggest that within the overall HRIA process health is given a narrower meaning, with the broader determinants of health left to be considered in the context of other rights (Radstaake and de Vries 2004).

HOM has also developed a ‘Health Rights of Women Assessment Instrument’ (HeRWAI) as an advocacy tool for non-government organisations seeking to influence government policies that affect women’s health (Bakker 2006). The impact of a policy is assessed by considering a set of questions, which are accompanied by a checklist of qualitative indicators. These questions and indicators are derived from a right-to-health framework which recognises that the right to health requires the availability, accessibility, acceptability and quality of health care and other determinants of health; people have the right to participate in decisions that affect their health; and violence against women is a violation of women’s right to health.

In addition to these initiatives, the Commission of the European Communities (CEC) has outlined a methodology for ensuring that legislative proposals are scrutinised for compatibility with the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (CEC 2005a). The CEC’s methodology integrates the assessment of human rights impacts into its existing impact assessment framework by including a series of additional questions into the CEC’s impact checklist. That checklist is divided into economic, environmental and social impacts, with questions directed towards the assessment of fundamental rights being incorporated within those categories, although such questions are not explicitly framed in terms of human rights (CEC 2005a, paras 18–19; CEC 2005b).

Hria and the Right to Health

A clear indication to emerge from a brief review of existing HRIA methodologies is that the consideration expressly given to the right to health within HRIA is relatively limited where the HRIA process is intended to assess the full spectrum of rights enshrined in international human rights law. In these circumstances, despite the interconnectedness and indivisibility of human rights, as a practical matter, HRIA is forced to consider individual human rights in a relatively piecemeal fashion. That is, the most common approach is to identify a given right and attribute to it a series of questions that act as indicators as to the likely impact of the relevant intervention on that right. In ascribing those indicators, to avoid duplication within the HRIA methodology, the questions for each right will generally have a relatively specific focus. Accordingly, in relation to the right to health, questions tend to focus on health in a more biomedical sense. As a consequence, the assessment procedure may not identify that the right to health is likely to be impacted, even though impacts on a number of rights which are themselves determinants of health are predicted.

Of course, given that HRIA needs to be undertaken in the real world, HRIA cannot be all things to all rights, and it is likely that HRIA will tend to focus on certain human rights depending on the circumstances in which it is being applied (Hunt and MacNaughton 2006, 30). The HeRWAI developed by HOM demonstrates how different the assessment procedure looks where the focus of HRIA is specifically trained on health. However, this leads us back to HIA. HIA has developed increasingly well-established methodologies for examining health impacts; it is not distracted by the need to conceptualise impacts in terms of a range of different rights; and there are a number of clear synergies between HRIA and HIA. Indeed, in many ways, HIA is already implicitly operating in relation to a human rights discourse (O’Keefe and Scott-Samuel 2002, 737). These characteristics of HIA might therefore suggest that it is just as able as, and in many circumstances better able than, HRIA to operationalise the right to health.

The Synergies between HIA and HRIA

There are four features of HIA and HRIA that usefully elucidate the synergies between these two forms of impact assessment. First, both HIA and HRIA are generally democratic processes that emphasise the importance of participation. Engagement with relevant stakeholders as part of the assessment process is seen as both an empowering experience for affected communities and a means of gathering evidence about the likely impacts on the community (IBLF/IFC 2007, 6; Rights and Democracy 2007, 18; Halifax Initiative Coalition 2004, 19). In relation to HRIA, in particular, participation is an enabling mechanism, which allows communities to actively assert their human rights (Rights and Democracy 2007, 18). At other levels, it is a key aspect of both HIA and HRIA that people are able to participate in the preparation, implementation and evaluation of the relevant program or policy. Such emphasis on participation means that in both HIA and HRIA, the assessment process is as important as its outcomes.

Second, HIA and HRIA are equally concerned to identify the differential impacts of a proposed intervention. HRIA endeavours to do this through its consideration of the right to non-discrimination. It asks assessors to consider whether an intervention is likely to have a discriminatory effect on a group within a population, either at a general level or in relation to the exercise of specific rights by that group. HIA asks assessors to consider the same issues when it speaks to them in the analogous language of health equity, and seeks to ensure both that existing inequalities are not deepened and that new inequalities are not created by a particular intervention (Braveman and Gruskin 2004).

Third, there is a concurrence between HIA and HRIA in terms of their ability to assess how a policy or program is likely to impact on the broader determinants of health. That is, given the interconnections between health and human rights, when HIA sets out to assess likely impacts on the determinants of health, it is inevitably giving consideration to a similar set of questions as HRIA when it assesses the impact of an intervention on a bundle of identified human rights. Conversely, even though HRIA tends to focus its assessment on a biomedical model of health, it nevertheless implicitly addresses each of the determinants of health by reason of its consideration of those additional rights that are necessary to the full enjoyment of the right to health. Indeed, in many ways, the practice in HIA of categorising and assessing the determinants of health in order to facilitate a systematic method of impact assessment is akin to the methodologies of HRIA, which segregate individual human rights and consider the likely impact on each of those rights.

Finally, both HIA and HRIA advocate for a multidisciplinary approach to impact assessment. While HRIA, in practice, has not developed its methodologies to the same stage as HIA, it is nevertheless clear that HRIA is seeking to assess impacts on rights that span a spectrum of sectors. To do this most effectively, it is necessary to involve practitioners from those other sectors in the assessment process. Similarly, HIA, in its endeavour to assess the impact of a policy or program on the determinants of health, seeks to engage with a broad audience both inside and outside public health. In adopting this intersectoral approach, both HRIA and HIA are concerned not only to call on the technical assistance of experts in a range of disciplines but, even more importantly, also to enhance recognition among decision makers across sectors of the human rights or health implications of their decisions.

These synergies demonstrate that there is considerable affinity between the core values and principles of HIA and HRIA. Yet, it is also clear that, despite this affinity, the focus of HIA remains embedded in the public health space rather than in the human rights paradigm. This, therefore, raises for consideration the question of whether a focus on the right to health rather than health itself offers anything over and above what HIA already provides.

Why an Impact Assessment for the Right to Health?

Accountability

International human rights law is a formal body of law which imposes legal obligations on states. Accordingly, to speak of the right to health is to speak of a legal norm which is embedded in a framework that imposes clear and enforceable duties on states as duty-bearers. A failure to comply with those duties represents a violation of a state’s legal obligation and gives rise to enforceable claims by rights-holders.

Health, as understood from the public health perspective, is not invested with the same legal authority. Public health is quintessentially a social movement, and HIA is therefore a methodology that is founded on notions of social democracy (Mann 1997). This is reflected in the language of public health practitioners who describe HIA as deriving from ‘a belief that governments are benevolent in purpose and have the capacity to play an active role in developing a society based on principles of social justice’ (Mahoney and Durham 2002, 18). Within this paradigm, the failure of a government to act in the interests of good public health may give rise to moral culpability, but does not give rise to any form of legal accountability (Scott-Samuel and O’Keefe 2007, 213).

A method of impact assessment that focuses on the right to health therefore offers a legal framework of accountability that is not available through HIA. Where an assessment is made that a proposed intervention is likely to result in a violation of a government’s legal obligations, government decision makers are legally bound to take action in response to that assessment. This represents a significant advantage over HIA, which is ultimately reliant on the largesse of the decision maker to respond to a negative assessment in an appropriate way. In this regard, the accountability framework provided by a right-to-health impact assessment also has the potential to equip HIA with at least one mechanism for attempting to overcome the difficulties that it has experienced to date with respect to successfully influencing the decision-making process (Hunt and MacNaughton 2006, 13).

International Legal Standards