Sovereignties in dispute: the Komagata Maru and spectral indigeneities, 1914

Chapter 8

Sovereignties in dispute

The Komagata Maru and spectral indigeneities, 19141

Introduction

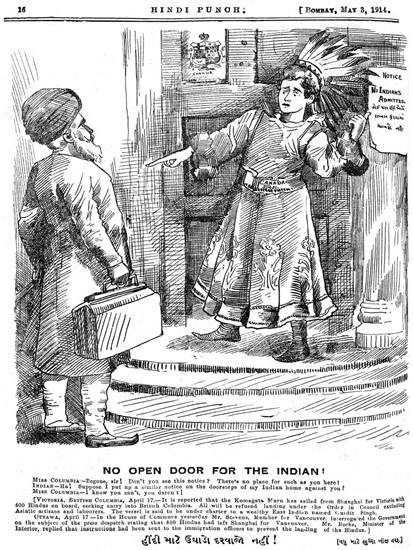

This chapter begins with the premise that indigenous dispossession and prohibitions on Indian migration in the British Empire were overlapping and conjoined legal practices that demand closer and more careful attention. To develop this argument, I focus on the 1914 journey of the Komagata Maru – a Japanese steamship that carried 376 Punjabi migrants from Hong Kong to Shanghai, Moji to Yokohama, and across the Pacific to its final destination in Vancouver, Canada. To date, the ship’s voyage – particularly the response it generated in North America – has been well documented by historians and others. The ship’s failed journey has become iconic; epitomizing the apogee of Canadian immigration restrictions and the emergence of new modes of governing mobility across the empire, exposing the racial contours of imperial subjecthood, and revealing the arduous conditions confronting migrants from Punjab who journeyed to North America in the early twentieth century.2 These are important and compelling histories. They foreground the Dominion’s longstanding efforts to fulfil its vision as a ‘white Canada’ and the legal regimes it used to do so. Although the Dominion had aspired to protect its borders from Indian migrants since at least 1908, the Komagata Maru was the first ship to be successfully sent back from Canadian waters. Its return to Calcutta instituted a racial regime of immigration prohibitions and regulations that remained in effect until 1947, when India finally gained independence from Britain.3 Notwithstanding the significance of these accounts, however, there are alternative histories to be written and additional questions to be asked, ones that bring indigenous dispossession and non-European migration more squarely within historical view. For example, how was indigeneity evoked in transcontinental struggles over the Komagata Maru? Why did colonial authorities and British Indian migrants introduce indigenous peoples into debates over mobility, migration and Dominion sovereignty, and to what effect?

For Marilyn Lake and Henry Reynolds, the large-scale migration of Europeans, Chinese and Indians to South Africa, the Americas and Australia was made possible only through the systematic displacement of indigenous peoples and the destruction of their communities. Migration, they argue, ‘rested on and required Aboriginal dispossession’.4 Yet, this provocative claim awaits further development. Lake and Reynolds offer little insight as to how aboriginal dispossession intersected with immigration regulations and prohibitions and how these processes differed with respect to European and non-European migrants. Migration from India and China, for instance, was not on the same footing as European migration but was premised on racial and territorial displacement and emplacement. As the Dominions dispossessed and destroyed aboriginal communities, they also restricted and eventually barred entry to Chinese and Indian migrants. Ultimately, these dual modes of exclusion legitimized Europeans as the rightful inheritors of the land.5 However, the force of Dominion sovereignty, I argue below, did not always necessitate the complete erasure of indigenous peoples. Placing histories of indigenous dispossession alongside those of British Indian migration opens other optics of mobility, settlement and sovereignty where the figure of indigeneity appears fleetingly and intermittently.6 In legal and political struggles over the Komagata Maru, indigeneity was evoked by colonial authorities and imperial subjects, albeit for different purposes and to achieve distinct effects. Importantly, what I call spectral indigeneities were never introduced by indigenous peoples on their own terms or for their own purposes. As we shall see, the deployment of indigeneity was not intended to signify real indigenous peoples. Nor was it to represent actual indigenous communities.7 Rather, spectral indigeneities, I argue, formed a recur rent motif and represented a nonhistorical temporality that was evoked by colonial authorities and British subjects to advance competing claims to sovereignty.8

Not Asiatics, Aryans, or ‘Native Indians’

One month after the Komagata Maru arrived and anchored in Vancouver Harbour, tensions between local authorities, the ship’s passengers and Vancouver’s Punjabi residents continued to escalate. Facing pressure from the imperial government and the ship’s supporters in London, India and elsewhere in the empire, and with no clear resolution in sight, the Dominion of Canada conceded that one passenger could come ashore as a legal test case to assess the constitutionality of the Dominion’s Immigration Act. These legal proceedings were to determine, once and for all, the fate and future of the ship and its passengers: could they stay in Canada, or were they to be sent back to Hong Kong, India or another British jurisdiction? Of central import were three newly enacted orders-in-council: the first disallowed the entry of unskilled labourers and/or artisans, the second required each ‘Asian’ entrant to be in possession of $200 upon arrival, and the third necessitated that passengers make a ‘continuous journey’ from their place of origin to Canada.9

The ship was chartered in Hong Kong by Gurdit Singh who left India in 1885 at the youthful age of twenty-six. He followed his father and brother to Malaya and later Singapore where he was involved in various pursuits including railway contracting. Gurdit Singh insisted that his primary decision to charter the Komagata Maru was to assist his fellow Indians who were stranded in Hong Kong and endeavouring to reach Canada. However, the journey’s broader imperative, he made clear from the outset, was to pose a legal challenge to the Dominion of Canada’s claims to sovereignty. By transporting Indian migrants across the Pacific to Vancouver, the voyage was to defy the racial inclusions and exclusions through which British subjecthood and mobility was determined. ‘We are British subjects and as devoted to the King as the nobleman in Park Lane or the coster in Whitechapel, [and] possibly more devoted than either,’ Gurdit Singh declared. ‘We are members of the Empire and we feel we have a right to live where we like within the bounds of the Empire.’10 The immigration hearing and the legal proceedings that followed were to address whether the passengers could lawfully stay in Canada. Was Canada legally authorized to deny entry to British-Indian subjects, or was the Dominion bound by legal and political obligations determined by the British Crown? Were the orders-in-council, which demanded passengers make a continuous journey and which targeted ‘unskilled labourers’ and ‘Asiatics’, discriminatory? And finally, were those aboard the Komagata Maru members of the ‘Asiatic race’ or were they ‘Aryans’ with filial ties to Europeans?

J. Edward Bird and K. C. Cassidy, two Vancouver lawyers who had previously represented the Punjabi community in recent immigration matters, were recruited by a group of local Punjabis known as the local ‘shore committee’.11 After perusing passenger lists, Bird and Cassidy identified Munshi Singh, a twenty-six-year-old farmer from the village of Gulupore in the Hoshiarpur District of Punjab, as the most suitable litigant. When the Board of Inquiry heard his case on 25 June 1914, the decision was unanimous: Munshi Singh belonged to ‘one of the prohibited classes enumerated in section 3 of the [Immigration] Act’. In the Board’s view, Munshi Singh contravened all three orders-in-council. At the time of his arrival in Vancouver, he had only $20, not the requisite $200, in his possession. Though claiming to be a farmer in Punjab, in Canada, the Board surmised, he would probably have been an unskilled labourer. Finally, the ship left Hong Kong and made numerous stops en route to Vancouver. Thus, Munshi Singh ‘had not come to Canada by continuous journey’.12 Based on these findings, the Board concluded that he and his fellow passengers should be deported.13

In response to the Board’s decision, Bird and Cassidy filed a writ of habeas corpus claiming that Munshi Singh ‘was refused permission to land’, was ‘ordered to be deported in the said vessel’ and was ‘being detained against his will as a prisoner on the said ship’.14 The writ was denied. However, Bird and Cassidy were granted an appeal at the British Columbia Court of Appeal. Here, their strategy was to question the Dominion’s sovereignty by placing the Immigration Act within a wider imperial context. The Canadian parliament, they alleged, had the right to exclude aliens but could not rightfully ‘authorize the detention and deportation of a British subject who presents himself at a port in Canada claiming the right to enter Canada as an immigrant’.15 On 6 July 1914, after only two days, the five appellate court judges reached a unanimous decision. They rejected Munshi Singh’s appeal. The Immigration Act, they agreed, was neither unconstitutional nor discriminatory; the three orders-in-council were well within the Dominion’s jurisdiction, and Canada could rightfully exclude Asiatics if she chose to do so. The British North America Act, opined Chief Justice Macdonald, awarded the ‘Parliament of Canada sovereign power over immigration’.16 The Dominion, Justice Irving added, ‘has a right also to make laws for the exclusion and expulsion from Canada of British subjects whether of Asiatic race or of European race, irrespective of whether they come from Calcutta or London’.17 Justice McPhillips reiterated this position, claiming that the ‘only privileged persons are those who in accordance with natural justice should be allowed free entry – by any nation – being her own Canadian citizens and persons who have Canadian domicil [sic]’.18

In making their appeal, Bird and Cassidy questioned whether the three orders-in-council were applicable to the case at hand. First, they claimed that the continuous journey provisions were irrelevant. British Indians, it was well known, regarded themselves to be part of a wider imperial fraternity that spanned continents. In its investigation into the circumstances surrounding the ship’s failed journey, the Komagata Maru Committee of Inquiry commissioned in Calcutta, explained that the ‘average Indian makes no distinction between the Government of the United Kingdom, that of Canada, and that of British India or that of any colony’. To him, these authorities are ‘all one and the same’.19 Espousing similar views, Bird and Cassidy argued that Munshi Singh ‘came direct from Hong Kong, and is a British subject’. As ‘a citizen of the Empire and therefore a native of the whole of it’, he is also ‘a native of Hong Kong’, which is part of the British Empire.20 Therefore, his ‘journey from that place to this was a “continuous journey from the country of which he is a native” and his ticket “a through ticket” therefrom’.21 As a ‘citizen of the Empire’, where political and legal distinctions between India, Hong Kong and Canada were immaterial, Munshi Singh arrived by way of continuous journey. Moreover, he was not an ‘Asiatic’, nor an ‘unskilled laborer’.22

The idiom of imperial citizenship that gained momentum in the early twentieth century, held ambiguous and contradictory meanings. As Sukanya Banerjee observes, it brought ‘to light formulations of citizenship before the inception of the nation-state’, while pointing to ‘the ways in which the British Empire itself provided the ground for claiming citizenship even as the thrust of these claims implicitly critiqued British colonial practices’.23 Imperial citizenship was mobilized as a basis from which to make claims to sovereignty and mobility and to critique the Dominion’s immigration policies. It provided one expression through which British Indians could forcefully assert their own demands for inclusion and equality within the imperial family. It also engendered an unequivocal condemnation of Dominion sovereignty. Since Munshi Singh was ‘a citizen of the empire’ who did not differentiate between colonial jurisdictions, the continuous journey provisions, Bird and Cassidy concluded, were inapplicable and irrelevant. However, the British Columbia Court of Appeal rejected their argument. Notwithstanding Munshi Singh’s understandings of the empire as a contiguous horizon, Justice Martin clarified that ‘the expression “country of which he is a native” is used in a geographical and not racial or national sense, and therefore, does not assist the applicant’.24 The appellant, the court concluded, was a resident of India and not of Hong Kong or of the empire, and thus did not come to Canada via continuous journey as legally required.

In their attempts to dispute Dominion sovereignty, Bird and Cassidy also queried the meanings and relevance of the term ‘Asiatic’. One order-in-council stipulated that ‘no immigrant of any Asiatic race shall be permitted to land in Canada unless such immigrant possessed $200’.25 The term Asiatic, they argued, was ‘ethnologically incorrect and too indefinite to be capable of application’.26 Munshi Singh, Bird and Cassidy insisted, was ‘not of the Asiatic race’ but of the Aryan one; the order-in-council that excluded Asiatics therefore did not apply to him.27 ‘It was asserted by counsel for the appellant,’ wrote Justice McPhillips, ‘that the Hindus are of the Caucasian race, akin to the English.’28 As with the continuous journey provision, the court rejected this claim. While Justice Martin described ‘Asiatic’ to be a ‘common sense’ term comparable to ‘European’ and ‘Latin-American’ and spoken in everyday conversations with shared consensus, Justice McPhillips introduced a series of expert knowledges, all drawn from British-European sources, to make a similar point.29 The Dominion had ‘the right to deport under the provisions of the Immigration Act and the orders in council irrespective of race’, and ‘irrespective of nationality’, McPhillips claimed.30 Although belonging to the ‘Asiatic’ race was ‘in no way crucial’ to the case at hand, he offered an abbreviated account of the term’s British-European history. When ‘the words “Asiatic race” are used in the order in council’ they are ‘in their meaning, comprehensive and precise enough to cover the Hindu race, of which the appellant is one’, Justice McPhillips stated. ‘[As] early as 1784 an association was formed and named the Asiatic Society in Calcutta, to extend a knowledge of the Sanskrit language and literature.’ According to A. W. Williams, a well-known professor of Indo-Iranian languages at Columbia University, the Asiatic races included ‘the people of India’.31

Justice McPhillips did not stop there. To augment his claim that ‘Asiatics’ included Indians, he turned to the Encyclopedia Britannica (1910) as the authorizing voice on racial distinctions. Here, spectral indigeneity made its first appearance in the case:

The Aryans of India are probably the most settled and civilized of all Asiatic Races.… Asiatics stand on a higher level than the natives of Africa or America, but do not possess the special material civilization of Western Europe.… Asiatics have not the same sentiment of independence and freedom as Europeans. Individuals are thought of as members of a family, state or religion, rather than as entities with a destiny and rights of their own. This leads to autocracy in politics, fatalism in religion, and conservativism in both.32

The order-in-council was purposefully directed at the ‘Asiatic race’, Justice McPhillips wrote. Based on the expert sources he consulted, this included British Indians. Never commenting on the putative superiority of ‘Asiatics’ over indigenous peoples in Africa or America, McPhillips explained that the Dominion’s refusal to allow entry to British Indians was premised on questions of desirability, suitability and assimilability.33 Ultimately, Canada was authorized by the British North America Act to pass laws in the interests of peace, order and good government.34

The five appellate judges agreed that Canada’s Immigration Act was neither unfairly discriminatory nor ultra vires. Justice Irving claimed that the orders-in-council were equally applicable to all, irrespective of race and nationality; they only added to an already long list of exclusions under the existing Immigration Act. Chief Justice McDonald recognized that the order-in-council ‘could not be, and was not intended to have been made operative without discrimination in favour of some races whose legal status to be admitted to Canada was already fixed by statute or treaty’.35 Justice Martin added that ‘the exercise of Federal jurisdiction necessarily often affects civil rights… the most striking illustration of which occurs in connection with quarantine’.36 Charges of racial inequality, such as the ones initiated by Bird and Cassidy, glossed over an integral point: British subjects did not enjoy a shared political or legal status, nor were they entitled to equal treatment across the empire. Justice Martin went even further and emphasized the racial unevenness of imperial belonging by drawing explicit comparisons between British Indians and indigenous peoples. Here, the spectral force of indigeneity emerged again. ‘Much was said about discrimination between the citizens and races of the Empire,’ Justice Martin explained. It ‘was suggested [by Bird and Cassidy] that Canada had not the right to exclude British subjects coming from other parts of the Empire’.37 Discrimination, he clarified, ‘was not a ground of attack upon an Act of Parliament within its jurisdiction’. The enactment and enforcement of legislation, he elaborated, ‘constantly and necessarily involves the different treatment of various classes, even of the Crown’s own subjects’.38 The spectre of indigeneity fortified his insistence on the legality and legitimacy of Canadian sovereignty.