Variations in Member State Use of Preliminary References

2

VARIATIONS IN MEMBER STATE USE OF PRELIMINARY REFERENCES

1. Overview

This chapter examines various questions concerning the reference patterns of Member State courts. In what follows, we first set out to examine in which Member States the courts actually use the preliminary reference procedure and in which Member States the courts do not (section 2). We then examine a number of different explanations that have been put forward in order to explain the perceived disparity with regard to the different Member State courts’ willingness to refer (section 3). On the basis of these examinations, we point out what, in our opinion, can be concluded with regard to the identification of factors that are relevant in explaining the apparent differences in propensity to make preliminary references (section 4).

2. The Distribution of Preliminary References among the Member States

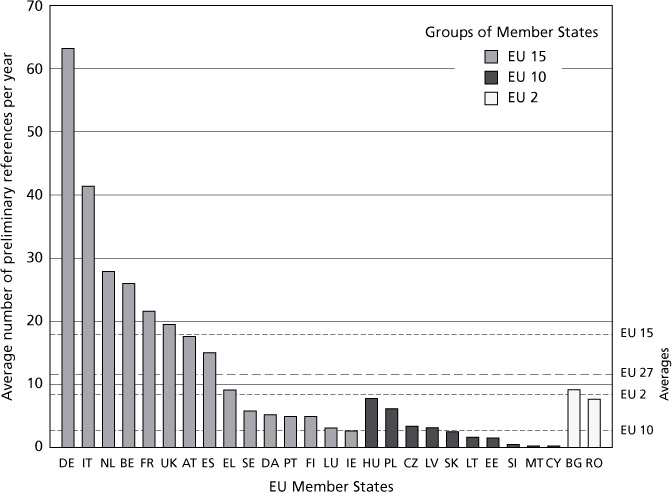

Figure 2.1 shows the average annual number of preliminary references for the 27 Member States (not including Croatia).

Figure 2.1 shows a wide variation in the number of preliminary references from courts of the different Member States. In general the number of references from the EU15 courts is markedly higher than the number of references from the EU10 and EU2 courts. This difference is a reflection of the fact that there is normally a certain time lag before the full weight of a new Member State is reflected in the Court’s case-load. In other words, the number of preliminary references from the courts of a given Member State is usually significantly lower in the first years of membership. Indeed, this is also reflected in the fact that the differences between new and old Member States are much less significant at the time of writing the second edition of this work as compared to the situation in 2009 when the first edition of the present work was finalized.2 Moreover, the number of references also varies appreciably within each of these three groups of Member States. In section 3 we discuss possible explanations for why this is so.

Figure 2.1 Average number of preliminary references per year in Member States1

3. Why Do Courts in Some Member States Refer More than Others?

3.1. Overview

As we have seen in the preceding section, there are considerable variations in the number of references stemming from the different Member States. Essentially, a preliminary reference presupposes two things: first, there must be a case before a Member State court that gives rise to EU law issues that may form the basis for a reference; second, the judge or judges sitting on the bench of the national court in question must decide to actually make a reference. The first condition concerns structural factors, whereas behavioural factors are the basis for the second. Basically, the behavioural factors concern which Member State courts are reference-averse and which courts are prone to refer. However, in order to make such comparison, it is necessary first to clarify what role is played by the structural factors.3

Imagine, for argument’s sake, that in Member State A there are 200,000 court cases annually that may give rise to a preliminary reference, whereas in Member State B there are only 10,000 such cases, and in Member State C there are none. In this situation it would seem to be a trite observation that, even if Member States B and C produce fewer preliminary references than does Member State A, this is not (necessarily) a reflection of Member States B and C courts not being prepared to use the preliminary reference procedure. Moreover, if we compare the number of court proceedings between, for instance, Malta and Germany, these differ very considerably.

Therefore, when assessing national judges’ willingness to engage the Court of Justice in cases pending before them it would be misleading to simply make the comparison on the basis of the actual number of references from the courts of, say, Germany and Malta. Instead, the comparison must be based on the number of preliminary references relative to the number of court cases that give rise to EU law issues in the Member States in question. In this regard we are faced with the challenge that there are no reliable figures for the number of national court proceedings giving rise to issues of EU law, and that ascertaining such figures with precision is virtually impossible. First, only a fraction of the total number of Member State court rulings is published. Second, only ‘a court or tribunal’, as defined in Article 267 TFEU, may make a preliminary reference, and this definition differs from the Member State definitions of ‘a court or tribunal’, thereby affecting the suitability of Member State statistics regarding the number of national cases.4 Whilst acknowledging the inherent deficiencies of the available data, we will nevertheless attempt to examine the Member State courts’ use of the preliminary reference procedure based on these data. Later, in section 3.2, we will consider different structural factors which may affect the number of cases that may lead to a reference. Whereupon, in section 3.3, we will consider the behavioural factors that have been held to influence national courts’ willingness to make a reference where a given case may give rise to a reference.

3.2. Structural Factors Possibly Determining National Courts’ Abilities to Make Preliminary References

3.2.1. Introduction

In this section we analyse to what extent the variations in the absolute number of references may be explained by differences in the number of cases that could form the basis of a reference (structural factors). An answer to this question will also act as an indication as to the extent to which it is possible to explain variations in references by circumstances that are unrelated to possible differences in the relative willingness of the various courts to make preliminary references (behavioural factors). Thus, first we analyse the relevance of Member State population size (section 3.2.2). Next we consider willingness to litigate in the different Member States (section 3.2.3). And finally we examine Member State compliance with EU law (section 3.2.4). Examining these three factors is not novel in itself. Rather, what is novel is to examine them together, and in particular our attempt at combining them to see whether—jointly—they may provide a better explanation of the variations (section 3.2.5).5 The Member State jurisdictions differ in many respects, including also in ways that may appreciably influence the actual number of preliminary references—without necessarily being related to the judges’ willingness to make such references. These special factors we briefly consider in section 3.2.6. Finally, in section 3.2.7, we state to what extent, in our opinion, our examination supports the view that structural factors may provide part of the explanation of the variations in preliminary references amongst the different Member State courts.

3.2.2. Differences in population size

In smaller countries, there are fewer people and undertakings to initiate legal proceedings, and thereby create the basis for a preliminary reference, than in larger countries. Therefore, all things being equal, it seems reasonable to expect that the number of cases in which there is a basis for making a preliminary reference is somehow correlated with the size of a Member State’s population.6

Moreover, the larger a Member State’s population, the more attractive it will normally be as a market for exporters in other Member States. The incentive to challenge impediments to trade is, therefore, greater with regard to the legislation of the larger Member States than with regard to that of the smaller ones. The greater the number of such legal challenges, the more cases there will be that may lead to a preliminary reference. Indeed, it has been calculated that, of the 832 references concerning free movement of goods that had been made up to 1998, 303 concerned challenges to German legislation. Whereas this could indicate that German legislation has been particularly protectionist, another explanation could be that the German market’s considerable size has led to a greater interest for those trading the goods in challenging those parts of German legislation that allegedly impede trade.7

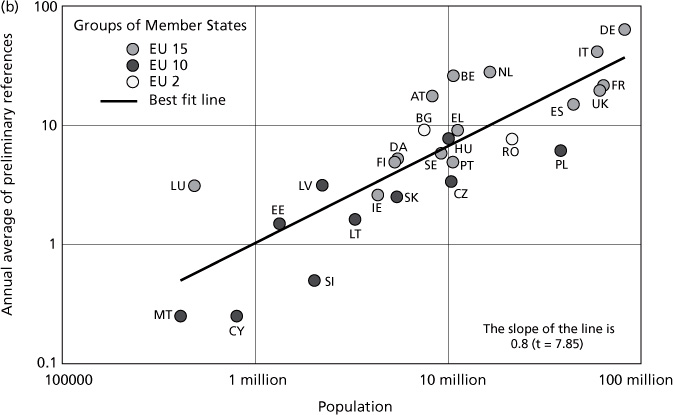

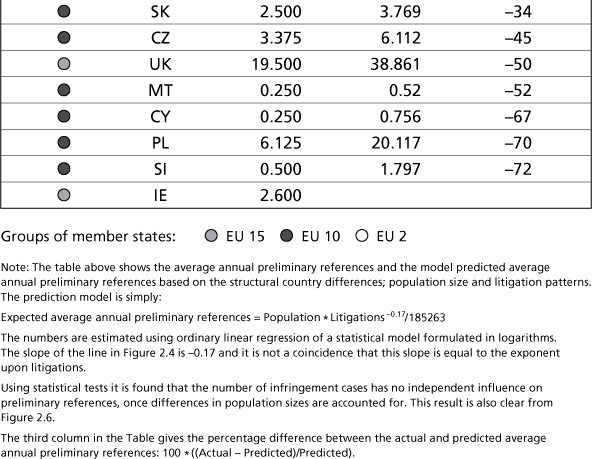

It may be difficult to see from a classical column diagram, like the one in Figure 2.2a, whether there appears to be any correlation between population size and the number of references. However, if we transform Figure 2.2a into a double logarithmic coordinate system (see Figure 2.2b), we will see that, apparently, there is such correlation.

Figure 2.2a Annual average of preliminary references relative to population size8

Figure 2.2b EU Member States by population and annual average of preliminary references

Figures 2.2a/b arguably show that, when one takes account of the difference in Member State population size, the variations diminish significantly. Hence, the figures appear to rather strongly support our assumption that there is a certain link between population size and the number of preliminary references made from each Member State. The slope of the regression line indicates that a 10 per cent difference in population sizes between two countries is associated with an 8 per cent difference in the number of preliminary references, and the t-statistic is 7.85 thereby indicating a statistically significant relation between the two variables.

Nevertheless, the figures vary widely, even for countries that have more or less the same population size. For example, German and Italian courts make more than twice as many preliminary references per inhabitant as do French and UK courts. Likewise, in relative terms, Austrian, Belgian, and Dutch courts make three to five times more references than do Irish and Portuguese courts, while courts in the Nordic countries lie somewhere midway between these two groups. Thus, while Member State size is arguably a factor that partly explains the differences in the number of preliminary references, other factors must also be taken into account.

3.2.3. Litigation patterns

As already indicated, a second factor that arguably may influence the number of cases in which questions of EU law arise before the national courts, and thereby provide the basic condition sine qua non for a national court to consider when making a reference, is the fact that in some Member States there is a relatively lower tendency to resolve disputes through the courts than by the use of other means. Or to put this in different terms, the litigation rate may vary significantly among the Member States.

In order to consider the assumption that a high rate of litigation in a Member State, all things being equal, correlates with a high number of preliminary references we may first turn to the number of judges relative to population size as an indicator for a Member State’s willingness to litigate. Thus, in a study by Blank, van der Ende, van Hulst, and Jagtenberg of the number of (non-lay) judges per 100,000 inhabitants in 11 EU jurisdictions, it was found that, at one extreme, Denmark had the lowest number of judges relative to population size (six per 100,000). At the other end of the table, Germany, with 23 judges per 100,000 head of population, in relative terms, had about four times as many judges.9 This may be compared with the average annual preliminary references per 10 million inhabitants of 9.5 for Denmark and 7.7 for Germany. Among the other Member States considered in the study, Poland, Italy, Belgium, and Sweden also had about 20 judges per 100,000 inhabitants. Austria and Belgium, which both have particularly high numbers of references relative to population size, also both have relatively high numbers of national judges per inhabitants. These figures arguably lend some support to the view that there is a certain association between a Member State’s rate of litigation (here, number of judges relative to population size) and the number of references originating in the Member State, although it is equally clear that this support is far from unambiguous.10

Perhaps a more straightforward way of examining whether a high rate of litigation in a Member State, all things being equal, correlates with a high number of preliminary references is to compare the actual number of court cases in a Member State with the number of preliminary references originating in that Member State. This approach is, however, faced with several challenges. First, as already explained in section 3.1, the Court of Justice applies an EU notion of Article 267 TFEU’s reference to ‘court or tribunal’. This implies that many quasi-judicial bodies that are not viewed as courts in the various national legal systems are nevertheless competent to make preliminary references.11 In some Member States, these quasi-judicial bodies may account for a very considerable number of cases, including those raising questions of EU law, while in others they do not. Second, due to the marked inadequacy of the available data on the different types of cases we have had to base ourselves on data for only civil cases.12 Third, the data provided earlier do not indicate the proportion of national court cases that give rise to issues of EU law before the various Member State courts, but this information does not appear to be available by other means.

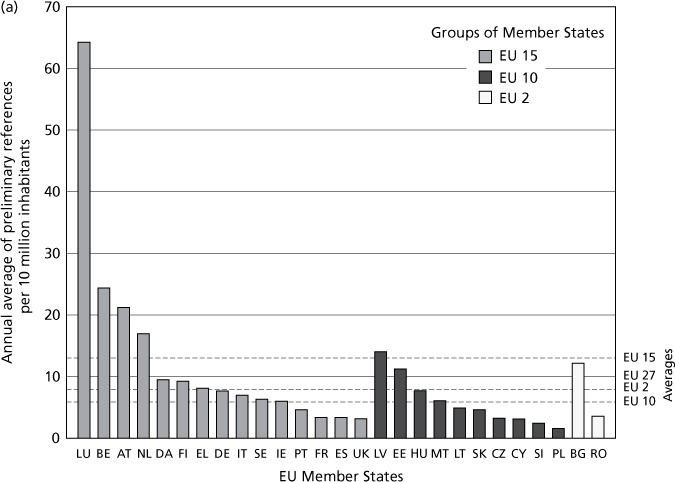

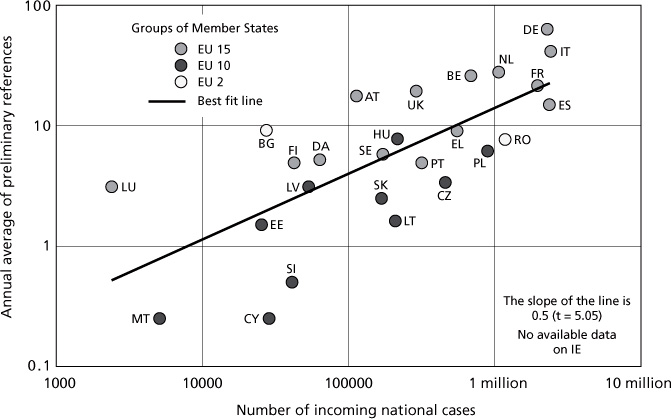

Accepting these provisos, on the face of it seems to show a rather clear correlation between these two factors as will be apparent from Figure 2.3. This finding corresponds with that of Vink, Claes, and Arnold, who equally found that a high national litigation rate generally tends to correlate with a high number of preliminary references from the Member State in question.13

Figure 2.3’s correlation between, on the one hand, litigation pattern and, on the other hand, number of preliminary references, is based on total number of national cases. However, it seems only natural that we may expect more such cases in larger Member States as compared with the smaller ones. The question therefore is whether the correlation remains if we exclude the size of the Member States in our calculation.

Figure 2.3 EU Member States by litigation rates and average annual preliminary references14

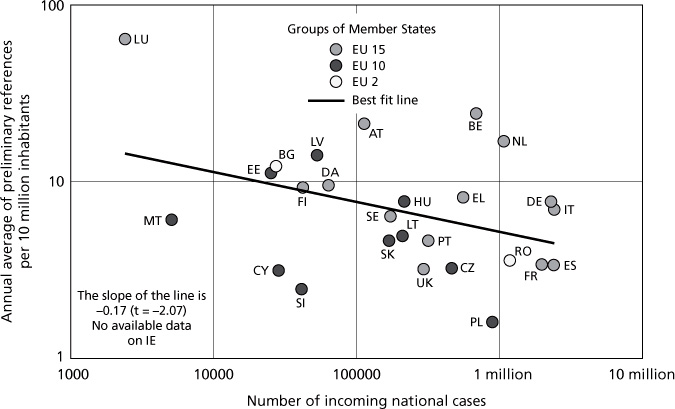

As is apparent from Figure 2.4, the t-value is just above 2 which means that we may consider there to be a significant relation between the two variables. In other words, based on our somewhat inadequate data we find that willingness to litigate seems to provide a partial factor for explaining why some Member States make more preliminary references than others. However, we also observe that this factor only carries rather limited weight since a difference of 100 per cent in the number of incoming cases is associated with a decline in the preliminary references of only 17 per cent, on average.

When considering the weight which may be attributed to the litigation factor, there are several factors beyond the national judges’ control that, in practice, are likely to affect the number of preliminary references from each Member State.

First, national rules on locus standi constitute one such factor, since in some Member States it may be appreciably easier to challenge national legislation and administrative practices than in others.

Second, the establishment under national law of public agencies whose task is to enforce EU law through litigation rather than through ordinary administrative supervision and enforcement may also stimulate an increase in the number of preliminary references.

Figure 2.4 EU Member States by number of incoming national cases and by annual average of preliminary references per 10 million inhabitants

In other words, in itself, the existence of certain Member State institutional actors can lead to more litigation, and thus, other things being equal, to a higher number of preliminary references.15