Arranged and Forced

Chapter 4

Arranged and Forced

Introduction

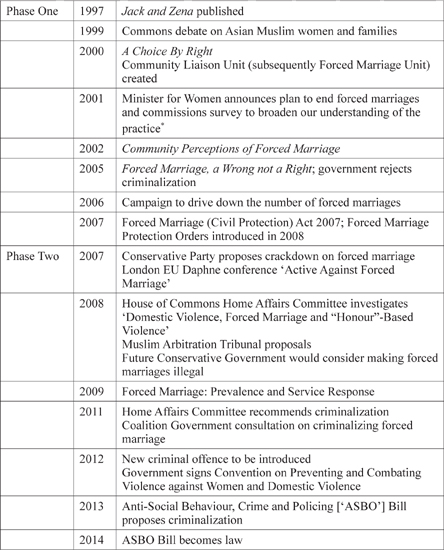

The context for debates about arranged and forced marriages which have taken place widely across Europe has been described in Chapter 1: the growth of minority families with continuing transnational ties to places of origin, who may seek to maintain practices at odds with those of the societies in which they have settled and in conflict with international conventions of gender relations and human rights, a consequent backlash against multiculturalism, amid a deepening crisis of trust regarding Muslims. Chapter 4 examines the progress of the UK debate from the late 1990s to the present over two phases:

• Phase One: up to the passing of the Forced Marriage (Civil Protection) Act 2007, and introduction of Forced Marriage Protection Orders (FMPOs);

• Phase Two: up to the legislation criminalizing forced marriage (Anti-Social Behaviour, Crime and Policing Act 2014).

Following an account of these developments, the chapter reflects on certain emergent themes, including the conceptualization of the arranged/forced distinction, the nature of coercion (physical and psychological) and female agency. A third phase, post the 2014 Act, is discussed at the end of this chapter and in Chapter 12.

It is sometimes believed that forced marriages, generally defined as ones without the full and free consent of both parties, are justified by Islam, but it should be clear from the outset that religious scholars maintain that Islam strictly opposes such marriages, and forced marriage is by no means confined to communities who happen to be Muslim. Nor is there any justification for the belief that forced marriages are part a cultural complex encompassing ‘honour killings, domestic violence, forced marriage and FGM … built on ideas of honour and cultural, ethnic and religious superiority’ (Brandon and Salam 2008: 1; see Korteweg and Yurdakul 2009). Undeniably, terrible things, including abuse and sexual violence, occur in Muslim families, as in others (Qureshi 2014), but notorious cases should not be made to stand for the values and practices of such families in general, or be allowed to demonize entire communities (Ewing 2006).

Table 4.1 Timeline of forced marriage debate in the UK

Note: *www.theguardian.com/politics/2001/nov/04/uk.politicalnews

Phase One: Forced Marriage Protection Orders (FMPOs)

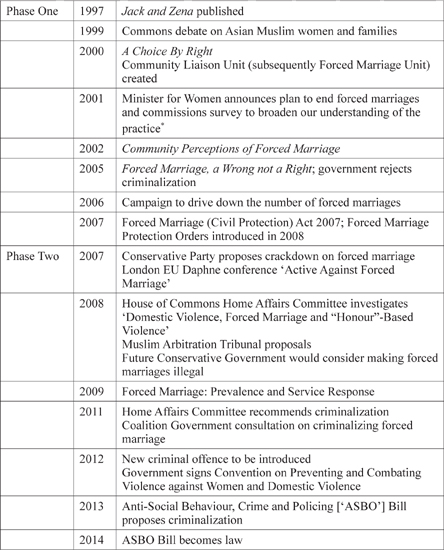

Following a widely-publicized case recounted in Jack and Zena (Briggs and Briggs 1997), Ann Cryer MP, then representing a constituency with a significant minority population, inaugurated a Commons debate on the treatment of Asian Muslim women by their families in which she focused on forced marriages.1 Subsequently the Labour Government, which had long been sensitive to issues of concern to its supporters among British Asians (for example abolishing the much-criticized primary purpose rule in 1997), established a working group to examine the question. All of its members had a minority background; given their prominence in public affairs they might be described as representing the minority establishment (Table 4.2). Their influential report, A Choice By Right (Home Office 2000), elaborated the principles guiding official response and action; its basic arguments, key phrases and tropes became common currency and were frequently repeated (Phillips and Dustin 2004).

Table 4.2 Composition of the Forced Marriage Working Group

Lord Nazir Ahmed, co-chair

Baroness Pola Uddin, co-chair

Lord Navnit Dholakia, chair of the National Association for the Care and Resettlement of Offenders, member Home Secretary’s Race Relations Forum

Yasmin Alibhai-Brown, author, journalist, member Home Secretary’s Race Relations Forum

Surinder Singh Attariwala, education and language consultant

Thomas Chan, member of Metropolitan Police Committee, Home Secretary’s Race Relations Forum, Deputy Chairman of the Chinese in Britain Forum

Humera Khan, An-Nisa Society

Rita Patel, chair of 1990 Trust, Director of the Belgrave Baheno women’s organization

Hannana Siddiqui, SBS

Source: Home Office 2000: 28

The minority composition of the working group did not necessarily reflect a wider positive engagement by all Asian communities with the forced marriage debate, and there was criticism from some quarters that members were colluding in an Islamaphobic government agenda to restrict the immigration of Asian spouses by defining arranged marriages as forced and demonizing the cultural practice as human rights abuse. The report, however, made clear that it was not concerned with arranged marriages. The difference between arranged and forced marriages which affect some men as well as women (not least men who are gay, Chantler et al. 2009; Khanum 2008; Samad 2010), resided in the right to choose, as the report’s title signalled, and quoting a remark (‘Multicultural sensitivity is no excuse for moral blindness’) by Home Office Minister Mike O’Brien,2 it argued that although ‘in a multi-cultural, multi-faith society like the UK we must value and celebrate our diversity. Equally, we must not excuse practices that compromise or undermine the basic rights accorded to all people’ (p. 10). Consequently, while it was necessary to understand parental motives, this did not mean accepting ‘justifications for denying the right to choose a marriage partner’ (p. 14).

Nonetheless, it contended, discussion of forced marriage should not be allowed to stigmatize British Asian communities. Such communities, led by minority women’s NGOs, were at the forefront of tackling forced marriage and domestic violence. They included the SBS (represented on the Working Group by Hannana Siddiqui, who subsequently resigned in a dispute over mediation, see Chapter 12 and SBS 2002, Siddiqi 2003), the An-Nisa society (also represented), Apna Gar (Asian Women’s Domestic Violence Project) in East London, the Asian Women’s Resource Centre, the Henna Foundation in Cardiff, Imkaan, the Muslim Women’s Helpline and the Muslim Parliament, which in 1999, in association with the Muslim Women’s Institute, had launched the Stop Forced Marriages Campaign3 (now subsumed within the Save Your Rights charity;4 Maqsood’s Thinking About Marriage 2005a was published as part of that campaign). Particularly influential was Derby-based Karma Nirvana, which in January 2014 celebrated its 21st anniversary with a reception at the House of Commons, hosted by the All-Party Parliamentary Group on ‘Honour’ Based Abuse, and addressed inter alia, by Baroness Caroline Cox.5 The contribution of its founder and long-standing activist against forced marriage and violence against women, Jasvinder Sanghera (recipient of a Pride of Britain award, and a CBE6) cannot be underestimated.

Responding to the recommendations of Choice By Right, the government established a Community Liaison Unit, subsequently Forced Marriage Unit (FMU, note the change in terminology) to deal with cases brought to its attention. Based initially in the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, but later jointly with the Home Office, the Unit currently (2014) explains that a forced marriage occurs when

one or both people do not (or in cases of people with learning disabilities, cannot) consent to the marriage and pressure or abuse is used … The pressure put on people to marry against their will can be physical (including threats, actual physical violence and sexual violence) or emotional and psychological (for example, when someone is made to feel like they’re bringing shame on their family). Financial abuse … can also be a factor.7

Working with a standard template (father/brother/mother forcing daughter/sister, sometimes son/brother into an unwanted marriage, or preventing them marrying their chosen partner) the FMU was, by the mid-2000s, handling several hundred cases a year, though there were claims that these represented a fraction of the total (see below). Subsequently, the number of instances where the FMU gave advice or support over a possible forced marriage rose to 1,735 in 2010, but fell back to 1,302 in 2013.

As a preliminary part of a strategy for engaging with communities to tackle forced marriages, the Unit commissioned a study of Bangladeshis in London and Pakistanis in Bradford (Samad and Eade 2002) to provide a better understanding for officials in the Home Office and elsewhere in government about the socio-cultural underpinning of arranged marriages, and an insight into views of, and contexts for, forced marriages as perceived by members of the community. Along with guidelines for social workers, health professionals, teachers and the police, the study was one of several initiatives aimed at improving the ability of public bodies to confront the sensitive issues arising from such cases.

While community engagement was the initial watchword, the difficulties encountered in implementing such a strategy (and the problems around engaging with collectivities in the backlash against multiculturalism) led to a focus on prevention and a (re)consideration of the possibility of making forced marriage a crime, an idea rejected in the FMU’s first year. When, with the volume of cases increasing, the government instituted a consultation (Home Office 2005), many respondents opposed criminalization (for example, MCB 2005), principally on the grounds that it would deter reporting. The government concluded that the ‘disadvantages of creating new legislation would outweigh the advantages … victims could become isolated, reconciliation could be prevented and forced marriage could be driven underground’ (FMU 2006: 11). Although this was welcomed by some, others were dismayed: ‘Despair as Forced Marriages Stay Legal’(The Times, 24 July 2006), and in November 2006 the Liberal Democrat peer and human rights activist, Lord Anthony Lester, proposed a Private Members’ Bill to make forced marriage an offence for which the victim could seek redress through the courts.

The Bill, which was backed by NGOs such as the SBS, who believed that such legislation would have an important deterrent effect without running the risk of driving the problem underground,8 became the Forced Marriage (Civil Protection) Act 2007, ‘protecting individuals against being forced to enter into marriage without their free and full consent and for protecting individuals who have been forced to enter into marriage without such consent’.9 Under the Act courts may make a Forced Marriage Protection Order (FMPO):

to protect the victim or the potential victim and help remove them from that situation. The courts will have a wide discretion in the type of injunctions they will be able to make to enable them to respond effectively to the individual circumstances of the case and prevent or pre-empt forced marriages from occurring. Courts will be able to attach powers of arrest to orders so that if someone breaches an order they can be arrested and brought back to the original court to consider the alleged breach.10

A problematic issue was and remains when does persuasion become pressure, and pressure force? Choice By Right identified a

spectrum of behaviours behind the term forced marriage, ranging from emotional pressure, exerted by close family members and the extended family, to the more extreme cases, which can involve threatening behaviour, abduction, imprisonment, physical violence, rape and in some cases murder. People spoke to the Working Group about ‘loving manipulation’ in the majority of cases, where parents genuinely felt that they were acting in their children and families best interests (2000: 11).

Drawing on legal precedents, notably Hirani v Hirani [1983], the 2007 Act defined force as ‘coerc[ing] by threats or other psychological means’. Whether this would include the emotional blackmail reported by Sanghera (2007) or Manzoor (2007), which might occur in any family (‘I’ll never be able to raise my head in public again!’) remains contentious; see further below.

Phase Two: Towards Criminalization

Lord Lester’s Act was not the end of the matter, and the controversy over forced marriages and their criminalization continued amid sensational media stories, confusion over numbers and further reports, conferences, consultations and interventions by politicians and activists of every stripe (Strickland 2013 has an excellent summary of the parliamentary developments). In autumn 2007, for instance, with the Conservative Shadow Immigration Minister, Damian Green, pressing for tougher action, Labour ministers affirmed that the possibility of criminalizing forced marriages remained open, and among a raft of measures proposed raising the age at which people could enter Britain for marriage from 18 to 21. The government also initiated a consultation on whether a relevant third party (for example a teacher or social worker) could bring an action under the 2007 Act (Enright 2009), and subsequently published guidance on how they might identify and assist victims (Ministry of Justice 2009).

Meanwhile, following a widely publicized inquest into the unlawful killing of a young Asian woman in which the coroner advised that the ‘concept of an arranged marriage was “central” to the circumstances leading up to her death’,11 the House of Commons Home Affairs Select Committee conducted its own investigation (2008) setting forced marriage in the wider context of domestic violence and concluding that there was a case for criminalization if the FMPO system was deemed unfit for purpose. In 2008, against the background of the Committee’s report, a survey was commissioned by the Department for Children, Schools and Families, in conjunction with the FMU, ‘to improve our understanding of the prevalence of FM, and … examine how services are currently responding to cases’ (Kazimirski et al. 2009: 11). The survey, whose methodology deserves greater scrutiny than can be accorded here, estimated that there were annually between 5,000–8,000 cases of actual or threatened forced marriage (in large part involving families with a South Asian, particularly Pakistani, background) which had come to the attention of police and social services, as against the 1,600–1,700 or so applications typically dealt with annually by the FMU. This estimate (which excluded a much larger number of hidden cases), though contested (SBS thought numbers were exaggerated, creating a moral panic to justify immigration policies12), was subsequently widely reported, and treated as authoritative. Such speculative figures are frequently recycled in the media and in parliamentary debates, but as with polygamous or sham marriages (Wray 2006), accurate data are unavailable and numbers always controversial (Rude-Antoine 2005), being dependent on what comes to the attention of the authorities and in what context.13

The survey also identified problems of awareness and training in the operation of FMPOs, and while recognizing that there were counter-arguments, observed that: ‘In the context of a generalised fear of cultural insensitivity, some statutory respondents argued for FM to be more clearly defined as a specific criminal act, suggesting that this would give many professionals increased confidence to detect and respond to it’ (Kazimirski et al. 2009: 38). The report noted concerns about the message FMPOs sent to communities, and contended that forced marriage ‘needs to be countered as a criminal infringement of liberty and rights, and clearly portrayed as a crime’ (p. 47). A later review of the progress of the 2007 Act and of the FMU was also critical of the operation of the statutory guidelines for dealing with forced marriages, concluding that while the nature of forced marriages was now better understood, and there were ‘pockets’ of good practice, responsible agencies (in education, social and welfare services and the police) lacked commitment, and training was poor.14 (See also Chokowry and Skinner 2009 and Gill and Anitha 2011 for criticisms of the FMPO system.)

In 2008 there was also an intervention by the MAT to address what it described as a ‘crisis’ which had ‘loomed within the Muslim community without being noticed or dealt with for the past two decades’ (2008: 9; see Bano 2011b, 2013; Griffith-Jones 2013b; Grillo 2012b). Specifically, it proposed to tackle forced marriages with overseas partners; a British partner would make a ‘voluntary deposition’ to be scrutinized by MAT appointed judges (sic) who would satisfy themselves that the proposed marriage was ‘without any force or coercion’ (2008: 7–8); that is, emotional, psychological or cultural pressure. Their declaration might then be used to support application for entry to the UK. In the event the marriage was deemed forced or coerced, the MAT might seek an FMPO. The proposal, which took little account of differential power relations within families (Bano 2011b), sought to protect the rights of British citizens who legitimately wished to arrange a marriage with a partner from the subcontinent and differentiate such arrangements from cases where pressure was employed to create a marriage of convenience. This would have positioned the MAT as an interlocutor with the government, establishing a sort of supplementary jurisdiction, and enhancing the MATs claim for recognition in legal matters (Prakash Shah, personal communication).

Throughout this period there was growing international concern about forced marriages with increasing pressure for restrictive legislation. There was, for instance, an EU initiative ‘Active Against Forced Marriage’ (for example City of Hamburg 2009), which organized several international conferences; one held in London in 2007 was addressed by Nazir Afzal, Philip Balmforth, Aisha Gill, Anne-Marie Hutchinson, Jasvinder Sanghera and Hannana Siddiqui, all of whom were active in the British forced marriage debate (Foreign and Commonwealth Office 2007). NGOs also organized their own local and international campaigns in Europe and North America. In June 2008, for example, the Henna Foundation arranged a meeting at the House of Commons, addressed by Tariq Ramadan, on behalf of ‘Joining Hands Against Forced Marriage’, which invited people everywhere to pledge to help end forced the institution.15

David Cameron, when leader of the opposition, had in response announced that a future Conservative Government would consider making forced marriages illegal: subsequently, in a speech (2011) criticizing ‘state multiculturalism’ for encouraging parallel lives and ‘tolerat[ing] segregated communities behaving in ways that run completely counter to our values’,16 he referred to the ‘failure to confront the horrors of forced marriage’, and in a later address on immigration denounced forced marriages ‘as a means of gaining entry to the UK’. This is the practice, he continued, ‘where some young British girls are bullied and threatened into marrying someone they don’t want to. I’ve got no time for those who say this is a culturally relative issue – frankly it is wrong, full stop, and we’ve got to stamp it out’.17 The Home Affairs Committee also revisited the matter, inter alia taking evidence from Karma Nirvana, and an unnamed witness, described as a survivor of forced marriage. It recorded:

It would send out a very clear and positive message to communities within the UK and internationally if it becomes a criminal act to force-or to participate in forcing-an individual to enter into marriage against their will. The lack of a criminal sanction also sends a message, and currently that is a weaker message than we believe is needed. We urge the Government to take an early opportunity to legislate on this matter (Home Affairs 2011: 7).

Although the initial response to the report was circumspect,18 in another speech (October 2011) describing forced marriages as ‘little more than slavery’,19 Cameron announced that while aware of the counter-arguments, the government would press ahead with legislation to criminalize the breach of FMPOs, as in Scotland (Forced Marriage etc. (Protection and Jurisdiction) (Scotland) Act 2011). There would also be a consultation whether to criminalize forcing someone to marry, ‘working closely with those who provide support to women forced into marriage to make sure that such a step would not prevent or hinder them from reporting what has happened to them’. The consultation received some 300 written responses (many available online) which the government summarized as 54 per cent in favour of a new offence, 37 per cent against (Home Office 2012a). Additionally, a large majority felt that existing sanctions were being employed ineffectively, and there was a need to do more about prevention and supporting and protecting victims.

In any case, the government’s mind was already made up. Noting that forced marriage was criminalized in Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, Denmark, Germany, Malta and Norway (as well as Australia), it announced it had signed the Council of Europe’s Istanbul Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence against Women and Domestic Violence, whose Preamble recognized

with grave concern, that women and girls are often exposed to serious forms of violence such as domestic violence, sexual harassment, rape, forced marriage, crimes committed in the name of so-called ‘honour’ and genital mutilation, which constitute a serious violation of the human rights of women and girls and a major obstacle to the achievement of equality between women and men.20

Articles 32, 37 and 42 of the Convention obliged signatories to introduce legislation to criminalize forced marriage (including luring someone to another nation-state for that purpose), and to ‘ensure that, in criminal proceedings initiated following the commission of any of the acts of violence covered by the scope of this Convention, culture, custom, religion, tradition or so-called “honour” shall not be regarded as justification for such acts’. Additionally, a European Parliament resolution on immigrant women in the EU,21 called on member states

to take due account of the circumstances of women immigrants who are victims of violence, in particular victims of physical and psychological violence including the continuing practice of forced or arranged marriage and to ensure that all administrative measures are taken to protect such women, including effective access to assistance and protection mechanisms.

To implement the terms of the Istanbul Convention, the government affirmed that breaching a FMPO would become a criminal offence and forced marriage would be made illegal in the wide-ranging Anti-Social Behaviour, Crime and Policing Bill presented in 2013–14. This decision was welcomed by Jasvinder Sanghera who said that Karma Nirvana had

worked exceptionally hard to obtain the public’s view. This includes from the streets of England, stopping members of the public to hear their views right through to galvanising support from our many partners which involved speaking at numerous events. The views came in their thousands as we delivered several post bags containing over 2,500 postcards to Number 10 where 98% of the British public had spoken in favour of a criminal offence.22

Besides criminalizing breaches of FMPOs, the Act,23 which became law in early 2014, made it an offence (punishable by a fine or imprisonment), if someone:

• ‘Practises any form of deception with the intention of causing another person to leave the United Kingdom, and intends the other person to be subjected to conduct outside the United Kingdom that is an offence [under the Act or would be if the victim were in England or Wales]’.

As in the 2007 Act, marriage is defined as ‘any religious or civil ceremony of marriage (whether or not legally binding)’; this would include a nikah.24 In the parliamentary debate the clauses relating to forced marriage were accepted without amendment, though an additional clause concerning persons lacking capacity to consent to a marriage was inserted by the Lords (see below).

For/Against Criminalization: the Parliamentary Debate

In consulting about creating a new offence, the Home Office (2011a: 11–12) summarized the arguments for and against. On the one hand:

[It] could have a deterrent effect and send a clear signal (domestically and abroad) that forcing a person to marry is unacceptable; empower young people to challenge their parents or families; make it easier for the police, social services, and health services to identify that a person has been forced into marriage as existing legislation may not be easily linked with forced marriages; would provide punishment to the perpetrator.

On the other:

Victims may stop asking for help and/or applying for civil remedies due to a fear that their families will be prosecuted and/or because of the repercussions from failed prosecutions; Parents may take their children abroad and force them to marry or hold them there, to avoid a prosecution taking place in the UK; An increased risk that prosecution, or threat of prosecution, may make it more difficult for victims to reconcile with their families; The behaviour criminalised may overlap with existing offences.

The written evidence submitted included responses from Mencap, Imkaan, a Police and Crime Commissioner and jointly and separately from Aisha Gill of Roehampton University,25 SBS and Ashiana Network. Aisha Gill’s contribution, which incorporated a valuable summary of the pros and cons (see also Gill 2011; Gill and Anitha 2011; Proudman 2011; Wilson 2014), acknowledged that forced marriage was an infringement of human rights, and criminalization would have a symbolic value (and send a message), but contended that,

The argument for criminalization ignores the practicalities of prosecuting forced marriage as a crime and the adverse effect such prosecutions may have on victims, especially given that most forced marriage cases would be heard before a judge and jury. The criminal justice system in the UK is adversarial. The victim, and any witnesses whose evidence is relied upon, are required to give oral evidence and be cross-examined. Evidentiary rules require that full disclosure be made to the defence team of all materials held by the prosecution, whether these are to be used or not. Often confidential and highly sensitive information is gathered by the police, local authorities and other organizations when a complaint is made or information given about a possible forced marriage. If a case goes to court, victims must face the fact that not only will this information be shared and discussed in court, but that they may be questioned by the lawyer(s) for the defence, who may have little interest in sparing their feelings. As it is likely that many forced marriage cases would be vigorously contested if prosecuted in the criminal courts, consideration should be given to the impact on victims and informants of being embroiled as key witnesses in difficult and lengthy public legal proceedings (Public Bill Committee 2013: 99).

One disputed matter was whether criminalization would encourage or deter young women coming forward to report a threat of forced marriage. In its summary of responses, the Home Office noted:

Many of those in support felt that it would act as a deterrent and deliver a strong message that we would not tolerate this abhorrent practice and would prosecute perpetrators. It was also suggested that this approach would empower victims to come forward and report incidents of forced marriage because the issue of victims actually agreeing to marry under duress should not be under-estimated. Those against criminalization felt that it could drive the issue further underground, as victims would be less inclined to want to come forward if it would ultimately lead to members of their family being imprisoned. There were concerns regarding the issues of intent and the ‘burden of proof’ and that it could result in victims being taken overseas for the purpose of marriage at a much earlier age (Home Office 2012a: 5).

The Ministry of Justice report on the operation of the FMPO system had previously noted that ‘victims were fearful of being seen to criminalize their families even though the legislation deliberately provides for a civil remedy rather than criminal, as a move to pre-empt victims from being deterred from taking action’ (2010: 12). This had been widely observed (for example Gangoli et al. 2009: 425), indeed it was basic to the case of those who opposed criminalization. Nonetheless, Charlotte Proudman, who had undertaken research with survivors of forced marriage (Proudman 2011), recorded:

Having repeatedly heard that victims of forced marriage do not want to criminalise perpetrators of forced marriage, often their families, and that making forced marriage a crime will deter victims from coming forward, I was surprised to find that all of the women I spoke to were strongly in favour of criminalisation. In fact they appealed to me to put forward their views and ensure their voices are heard amongst saturated political and media rhetoric, which appears to have falsely portrayed their views. They argued that if forced marriage had been a criminal offence when they were forced to marry they would have used the law as a bargaining chip to negotiate with their parents. They believed that a criminal penalty would act as a deterrent, and also argued that legislation would have a symbolic function in sending a message to perpetrators that forced marriage is socially unacceptable. All of the women I spoke to said they wanted recognition of their rights and of the wrong that had been inflicted on them, and demanded that bringing perpetrators to justice and protecting victims should be prioritised over concerns about demonising the communities which practice forced marriage.26

All these points (for and against), which repeated much that had been said previously, were further rehearsed in the subsequent parliamentary debate and in the media. Thus a BBC2 Newsnight debate in June 2012 pitted Aneeta Prem27 of the Freedom Charity28 against Khatun Sapnara, a barrister (now judge29), working with the Ashiana Network,30 who had been involved with the development of the 2007 legislation. Prem argued that criminalization would be an add-on to existing legislation, give young people a better understanding of their rights and tackle child abuse and domestic violence. Sapnara contended that criminalization was surplus to requirements. It would have symbolic value, but do little practically and would drive the issue underground, and possibly overseas. Similarly, on BBC Radio 4s Sunday programme (10 June 2012) Tehmina Kazi31 of the British Muslims for Secular Democracy (BMSD) debated with Aisha Gill. Kazi supported criminalization as a bargaining chip for young people in danger of being coerced into marriage, arguing it would not deter people from coming forward. In Denmark criminalization increased reporting rates, and she could imagine young people threatening their parents that they would report them to the police. In a survey undertaken by Karma Nirvana only two out of 1,620 respondents had opposed criminalization.32 Besides, existing legislation did not cover emotional coercion. Gill accepted that forced marriage was a human rights violation and Islam and other religions agreed that people have a right to choose, but existing laws were sufficient. FMPOs protect victims and criminalization would deter victims from coming forward to seek support and remedies.33

There was an extended debate about the clauses relating to forced marriage in both Commons and Lords. There was universal agreement (again) that arranged and forced marriages were different, and that forced marriages were a serious problem which had to be tackled. There was disagreement about whether criminalization alone is enough (for example Wind-Cowie et al. 201234), with some arguing that more resources needed to be directed towards prevention, especially in the light of cuts in legal aid and support for women’s refuges: schools need to be better prepared to engage with what is a child protection issue. Other arguments linked forced marriage to child exploitation and grooming, sham marriages of convenience, the exploitation of people with disabilities and honour killings, again an old argument. In addition, Baroness Cox, returning to matters discussed in Chapter 3, sought to include an amendment making it an offence ‘if someone solemnises a marriage according to the rites of any religion or belief between two persons by virtue of which either or both persons believe themselves to be legally married (it not being a marriage solemnised or purporting to be solemnised’ [in terms of the Marriage Act]).35

Throughout, evidence from Karma Nirvana and Kazimirski et al. (2009) was constantly reiterated with, in the Commons, a general assumption that criminalization was inevitable, and supported by all the data. This was apparent at a Committee session,36 which heard from invited witnesses including Jasvinder Sanghera and Aneeta Prem, who explained the work of their organizations, and answered questions about the motives for forced marriage:

Aneeta Prem: The main reasons are around the family. It is about control. It is about money. It is about immigration and getting people to stay in the UK or come over. It is about having such a level of control over the young person that they lose their freedom. We are talking about young people who are born in the UK, and lose all the rights that you and I expect.

Jasvinder Sanghera: Controlling behaviour is one. Some family members operate a system of honour, and it deemed dishonourable to take on western behaviour, such as being seen talking to the opposite sex, wanting an education, wearing make-up and anything to do with integration. Often, families see such behaviour as a cause of shame, and a forced marriage may be a means of dealing with that sort of behaviour.

Both strongly supported criminalization because of the inadequacies of the FMPO system, and rejected the charge that criminalization would drive the problem underground – it already was. Criminalization would give the authorities greater powers and send out a very strong message.

Later the Committee interviewed Isabella Sankey and Katie Johnston of Liberty37 who while agreeing that breaching FMPOs should be a crime, were concerned about criminalizing forced marriage as such, as they had been in 2005.38