Trust Formation: Capacity and Formalities

Chapter 4

Trust Formation: Capacity and Formalities

Chapter Contents

The Fundamental Requirements Needed To Form an Express Trust

Formality Requirements on the Declaration of a Trust

Formality Requirements on the Disposition of an Equitable Interest

As You Read

In this chapter, you start to consider how the most widely used type of trust, the express trust, is formed. The express trust is a like a jigsaw: only when all of the pieces of the jigsaw are placed together will you see the main picture. It will take until (and including) Chapter 7 to understand how each component part of the express trust comes together. Here, look out for:

the fundamental requirements to form an express trust. An understanding of these component parts is essential;

the fundamental requirements to form an express trust. An understanding of these component parts is essential;

capacity: who can declare a trust, who may be trustees and who can benefit from a trust; and

capacity: who can declare a trust, who may be trustees and who can benefit from a trust; and

formalities: how, in some types of trust, the law imposes formal requirements if the declaration of trust is going to be enforceable.

formalities: how, in some types of trust, the law imposes formal requirements if the declaration of trust is going to be enforceable.

The Fundamental Requirements Needed to Form an Express Trust

The nature of an express trust was discussed in Chapter 2.

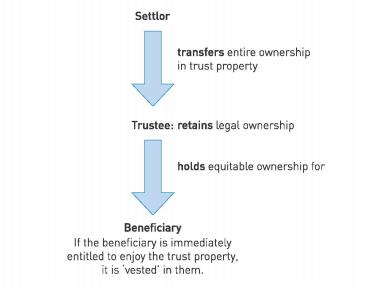

The diagram showing how an express trust is formed is set out below, in Figure 4.1.

The diagram at Figure 4.1 is a straightforward illustration of how an express trust is formed. The key transactions in the diagram need to be examined.

The settlor transfers the entire ownership in the trust property to a trustee

This part of the setting up of the express trust can be broken down into two critical stages, in which the settlor:

[a] declares the express trust; and

[b] constitutes the express trust.

Both stages need to be done properly if a valid express trust is created. Again, both stages have several parts to them. When the settlor declares an express trust, they need to adhere to four requirements. The express trust must comply with:

formal requirements;

formal requirements;

the three certainties;

the three certainties;

the beneficiary principle; and

the beneficiary principle; and

the rules against perpetuity.

the rules against perpetuity.

Formal requirements

The formal requirements needed for a trust depend upon the type of property which is to be the subject matter of the trust. To take the following examples:

[a] if the trust property is a chattel, that chattel needs to be delivered to the trustee and there must be an intention by the settlor to give the chattel to him;

[b] in the case of shares, any shares must be transferred to the trustee by making use of a Stock Transfer Form;1 and

[c] if the trust property is land, the terms of the trust must be evidenced in writing and declared by some person able to declare the trust.2 This requirement is considered later in this chapter.

The three certainties

It must be clear that there is certainty that the settlor intended to create a trust rather than simply intending to give the property away to someone. This is known as ‘certainty of intention’. It must also be certain what the subject matter of the trust is, or in other words, precisely what property the settlor placed on trust. Finally, the requirements of certainty mean that it must be possible to say who is going to benefit from the trust or, in legal parlance, certainty of object must be present. These certainty requirements are known as ‘the three certainties’. They are considered in detail in Chapter 5. As we shall see, the requirements of certainty are largely present to help the trustees administer the trust. The trustees must be able to be sure that the settlor intended to create a trust, what property the settlor expected his trustees to administer for the beneficiaries and lastly, who the beneficiaries are who will benefit from the trust.

The beneficiary principle

This principle requires that trusts in English law should usually be established for the benefit of ascertained or ascertainable beneficiaries. This means that they have already been identified, or are capable of being identified, as individuals or as being a member of a class of persons. In practical terms, this means that a trust should normally benefit an individual or individuals. Sometimes a trust may benefit a company because, in law, a company is generally seen to be a legal individual. A trust cannot normally be set up for a purpose, as opposed to an individual. Trusts for purposes generally do not comply with the beneficiary principle and will be void. There are exceptions to this requirement to have an ascertained or ascertainable beneficiary and these exceptions are considered, along with the beneficiary principle itself, in more detail in Chapter 6.

The rules against perpetuity

These are three rules which exist to ensure that a trust will start and come to an end at some point in the future. It is generally thought to be a bad thing to allow a trust to last forever. In the past, trusts were often used to manage property (usually vast estates of land) for wealthy families. The intention behind such trusts was to ensure the land remained in the same family. The danger with this intention is that, if this practice were widespread, it would be difficult for property to circulate freely in the economy. In a market economy, it is important that all types of property, both land and personal property, are allowed to be bought and sold easily and that there are as few restrictions on this ability to buy and sell as possible. The rules against perpetuity are considered in a chapter on the companion website.

Provided the settlor meets these four requirements, the express trust will have been declared successfully.

The settlor then needs to go on to ensure the trust is constituted. In theory, this is a relatively simple requirement. It means that the property of the trust must be properly transferred to the trustee. Constitution of a trust is needed so that the ownership of the trust property can be placed with the trustee and then the trustee can start to hold the equitable interest in the property on behalf of the beneficiary. Without transferring the property to the trustee, there can be no constitution, since the trustee would not own any property to administer on behalf of the beneficiary.

Of course, nowadays most express trusts are professionally drawn up by solicitors or accountants. This means that the requirements that the trust is properly declared and constituted should all be capable of being met in a document drawn up by the adviser. For such professionally drawn-up trusts, it is artificial to see the stages needed to declare a trust as coming one after the other: in truth, all the requirements to declare the trust and constitute it will be recorded in the same document. Nevertheless, to understand how such a modern trust may be drawn up, it is important to break down the separate requirements of declaring and constituting a trust and examine them in depth in the following chapters. The following four chapters, then, are all connected with this central theme of forming an express trust.

The trustee holds the property on behalf of the beneficiary

Once the trust has been validly declared and constituted by the settlor, it is ready to be used. That means that the trustee is subject to a number of duties and obligations, but enjoys some rights too in terms of administering the trust. The duties that the trustees are under, together with the rights that they enjoy, can be found in Chapters 8 and 9.

This begs the question: what type(s) of property can be left on trust?

Trust Property

Figure 4.1 illustrates the settlor transferring trust property to the trustee to hold on trust for the beneficiary’s enjoyment.

An express trust can be declared of virtually any property in which the settlor holds a legal interest. As mentioned, from the advent of trusts being first used, often trust property would amount to land. Wealthy families have made use of the trust for centuries as an attempt to ensure that land remained in their hands. But trusts do not have to have land as their property. ‘Trust property’ is used in a very wide sense.

Trust property may, for example, include the following, as well as land:

[a] Chattels. Sometimes these are known as ‘choses in possession’. They can be taken into the possession of someone or they are capable of being possessed. They are items which are not fixed to a piece of land, but are instead independent. In other legal systems, such as in France, they are known as ‘movables’ precisely because they can be moved about rather than being immovable, like land. This book that you are currently reading is a chattel, as is the chair upon which you are sitting to read it. If something is affixed to the land with the intention that it enhances the land, it ceases to be a chattel. For example, the washbasin and bath in your bathroom would not be seen as chattels since they are fixed to the land with the objective of enhancing the land.

[b] Money. Often trusts are set up with just money as their property.

[c] Choses in action. These are things which are dependent on the holder of them taking legal enforcement action (as opposed merely to taking physical possession of them) in order to obtain the rights associated with them. For instance, a share in a company is a chose in action. To obtain the money that it is worth, you would have to take legal action against the company and the company would pay you the value of it. The share certificate that you may have in your possession is merely evidence that you own a certain share in the company. Another example of a chose in action would be an insurance policy. Again, you would need ultimately to take legal action against the insurance company to enforce it.

All of these types of property are forms of ‘personal’ property, or ‘personalty’, so called because the rights in the property are enjoyed personally by the owner. The other type of property is known as ‘real’ property, or ‘realty’, which consists only of freehold land. This is called real property because the rights in it are real — they are rights that are enjoyed in the property itself, as against the whole world.

Often the property of a trust will be a mixture of all these different types of property. It is important to understand that not every trust will have land as its property.

EXPLAINING THE LAW EXPLAINING THE LAW |

Suppose Scott writes his will. He appoints Thomas and Vikas to be his trustees and provides that they are to hold on trust:

his gold watch for his cousin, Amy;

his gold watch for his cousin, Amy;

all of his shares in British Airways plc for his sister, Bethany;

all of his shares in British Airways plc for his sister, Bethany;

£100,000 in his bank account for his son, Charlie; and

£100,000 in his bank account for his son, Charlie; and

the house known as 4 Barlow Close, Derby, for his wife, Deborah.

the house known as 4 Barlow Close, Derby, for his wife, Deborah.

These are examples of Scott declaring four express trusts: one in favour of each of the four beneficiaries. Providing the four requirements for a valid declaration are fulfilled, constitution of the trust will occur after Scott’s death. Each of the four trusts has a different type of property. Only the final one has land as its trust property.

Capacity

It must be asked whether anyone can declare a trust, whether anyone can administer a trust and whether anyone can benefit from a trust. The capacity of each of the three main parties to an express trust — the settlor, the trustee and the beneficiary — must be examined.

The issue of capacity focuses on two concerns: whether the person under consideration has to be a particular age and whether the person must have mental stability in order to have capacity.

Capacity of the settlor

The general principle is that anyone can be a settlor of a trust and thus create a trust, provided they are at least 18 years old and are not mentally incapable. Of course, the settlor must own property and therefore must own the legal (or at least the equitable) interest in the property which they wish to settle on trust.

Children

It is possible for a child to settle personalty on trust. This trust is, however, voidable by the child, either before the child reaches 18 years old or within a reasonable time of reaching that age. This was shown in Edwards v Carter.3

Here, Albert Silber declared a trust in contemplation of a marriage between his son, Martin Silber and Lady Lucy Vaughan. The terms of the trust were that Albert was to pay the trustees the sum of £1,500 each year whilst Lady Lucy or any of their children were alive. The trustees were to pay that money, in turn, to Martin during his life and then, after his death or bankruptcy, to Lady Lucy and their children. The trust went on to say that if Albert left Martin further property under his (Albert’s) will, that property was to be held by the trustees in place of the annual sum of £1,500. This trust was declared by Albert whilst Martin was still a child. Approximately one month after the trust was declared, Martin became an adult.

Albert died in May 1887, nearly four years after declaring the trust. Martin attempted to repudiate the trust in July 1888 which, by then, was nearly five years after the trust had been declared.

The House of Lords held that Martin could not repudiate the trust. Whilst they affirmed the rule that a contract was voidable before a child reached 18 years old, or within a reasonable time of reaching 18 years old, their Lordships held that Martin had waited too long before repudiating the contract. Lord Watson explained the issue of repudiation as:

If he [the former child] chooses to be inactive, his opportunity passes away; if he chooses to be active, the law comes to his assistance.4

For our present purposes, the case illustrates that a child can be a settlor of a trust of personalty. The child also has the ability to repudiate the trust, either before he reaches 18, or within a reasonable time of reaching 18. What is a reasonable time will be a question of fact for the court to resolve: the House of Lords found it unnecessary in the case to set down what period of time was reasonable in every case.

A child cannot own the legal estate in realty. Under Sched 1, para 1 of the Trusts of Land and Appointment of Trustees Act 1996, any realty conveyed to a child will be held automatically on trust for them, so they will only be able to enjoy an equitable interest in the property. Since a child is himself a beneficiary of such a trust and is unable to deal with the legal estate in the realty, the most a child can do with realty is to declare a trust of their equitable interest.

Mentally incapacitated individuals

Whether or not a person suffering from mental capacity has the ability to declare a trust was considered in Re Beaney.5 The High Court held that whether a trust would be recognised depended on the size of the property being given away.

In the case, Mrs Maud Beaney owned her own home in Cranford, Middlesex. She had three children: Valerie (the eldest), Peter and Gillian. Mrs Beaney suffered from an ‘advanced state of senile dementia’6 from October 1972 until her death in 1974.

In May 1973, Mrs Beaney was admitted to hospital. Whilst there, Valerie claimed that her mother had decided to give her house to her. Valerie explained that this was in case the house needed to be sold at a future point to provide funds for the cost of her mother’s care. Valerie asked a solicitor to draw up a document, formally transferring the house into her name. The solicitor brought the document to Mrs Beaney and explained to her that if she signed it, its effect would be to give the house to Valerie absolutely. The solicitor asked Mrs Beaney twice whether she understood the nature of the document and on both occasions, Mrs Beaney confirmed that she did. The solicitor, Valerie and a third witness believed that Mrs Beaney understood what she was doing when she signed the transfer document.

After her death, Peter and Gillian argued that Mrs Beaney had lacked capacity to transfer the house to Valerie. They said that their mother was confused, as illustrated by her calling her family by incorrect names, having a tendency to get into the wrong bed whilst in hospital and by her handwriting being practically illegible. Valerie maintained that her mother did have capacity to transfer the house to her. She argued that the house was now hers, to the exclusion of Peter and Gillian.

Judge Martin Nourse QC held that the transfer of the property to Valerie was void due to a lack of capacity on Mrs Beaney’s part.

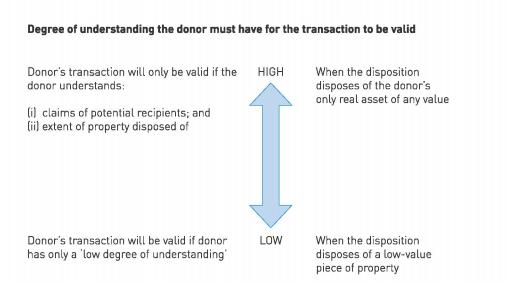

He said that there were different degrees of understanding required for lifetime transfers of property. The degree of understanding required was related to the actual transfer which was proposed. How much the individual transferring the property had to understand about the transaction varied depending on the value of the property being transferred and its relation to that individual’s other assets. He said:

at one extreme, if the subject matter and value of a gift are trivial in relation to the donor’s other assets a low degree of understanding will suffice. But, at the other extreme, if its effect is to dispose of the donor’s only asset of value and thus, for practical purposes, to pre-empt the devolution of his estate under his will or on his intestacy, then the degree of understanding required is as high as that required for a will …7

When writing a will, Martin Nourse QC reminded the court that the degree of understanding required was that the testator had to understand the claims of all potential recipients of his property and the extent of the property of which he was disposing. The requirements for understanding are summarised in Figure 4.2 below.

Applied to the facts here, Mrs Beaney was disposing of her home, which was her only real asset. The degree of understanding she needed to have for that transaction to be effective was as high as if she were writing her will. The reason for this was that she was effectively circumventing the need for a will, by divesting herself of her only real property by the transfer to her daughter. Mrs Beaney needed to understand first, that her other children might have at least moral claims to her home and second, that she was giving away her only real asset. She had effectively no other property of her own. The evidence of her confusion led to the conclusion that she could not have understood these two crucial issues. At best, the judge found that all she could have grasped was that the transfer had ‘something to do with the house’ and that the effect of it was ‘to do something which her daughter Valerie wanted’.8

Re Beaney was applied by the High Court in the more recent case of Re Sutton.9 This latter case illustrates how the test of whether the donor understands the nature of his gift is applied. Here, Norman and Rosalie Sutton lived in a bungalow in Tangmere, West Sussex. The house was in Norman’s sole name. He transferred it in August 1997 to his son, Mark, who later transferred it into his and his wife’s joint names. Norman and Rosalie continued to live in the bungalow. Norman died in 2005. Afterwards, Rosalie brought an action, claiming that the transfer of the house should be set aside. She argued that Norman lacked capacity when he signed the transfer.

The judge, Christopher Nugee QC, found that, unlike Mrs Beaney, the bungalow that was transferred was not Norman’s only real asset. He had several other investments. Yet the judge found that the house was his main asset. As such, the degree of understanding that Norman had to have to show capacity was a high one. It had to be shown that he understood not only the ‘general nature of the transaction but also the claims of other potential donees’.10

The judge pointed out that the burden of proof that a person lacked capacity lay with the person seeking to prove that the document was invalid. The evidence in this case was that Rosalie had to help Norman physically sign the document transferring the property to Mark. Mark admitted that he did not discuss the transaction with Norman and he was concerned that his father did not understand the effect of the document he was signing. Various entries from a diary kept by Rosalie confirmed Norman’s deteriorating mental health before and around the time that he signed the transfer document. A consultant neurologist’s view was that by the summer of 1997, Norman had significant cognitive decline which would have impaired his ability to understand a legal document and he did not believe that Norman would have had the high degree of understanding required from Re Beaney to ensure that the transfer he signed was valid.

Christopher Nugee QC accepted this evidence and held that Norman lacked capacity. In terms of the concrete proof that was needed for the transfer to have been valid, he said that Norman would have needed to understand that he was giving away the bungalow to Mark and that, as a consequence, neither he nor Rosalie would have had any right to remain in the house. To deprive himself and his wife of their matrimonial home was a serious consequence and, as such, Norman needed to demonstrate a high degree of understanding. The evidence showed that he did not have this.

The parties in the case not only wanted the judge to declare the transaction invalid but also that it was void.

Glossary: Void or Voidable?

If a document is void, that means that the document was never valid. It was of no effect at any time. Everything goes back to square one: it is as though there never was a transaction at all.

If, on the other hand, a document is voidable, this means that a document is valid, but that it may be set aside at the bequest of the innocent party. A good example occurs if the document was made as a result of a misrepresentation. The innocent recipient of the misrepresentation may well wish to have the document set aside — or, alternatively, they may be content to leave the document to have its normal legal effect. Such is possible if a document is voidable. ‘Voidable’ gives the innocent party some flexibility over whether they wish to rely on the document or not.

By the time of the hearing, Rosalie and Mark had been reconciled. The hearing was really about taxation and, in particular, the payment of capital gains tax.

Glossary: Capital Gains Tax

This tax is generally payable whenever an item is sold which has increased in value since it was purchased. A typical example might be a rare painting that was bought in 2000 for £1 million and is sold today for £3 million. Capital gains tax (CGT) is charged on the gain made — £2 million.

Reliefs exist and exemptions apply which mean that often no CGT is charged on everyday transactions. For instance, if a house is bought and then later sold, the principal private residence exemption will apply to the gain made. This means that no CGT is payable on the gain, provided that the owner used the house as his main residence whilst he owned it.

For more information on capital gains tax, see www.hmrc.gov.uk/cgt/.

Rosalie and Mark feared that if the transaction was held to be valid, Mark would have acquired the bungalow in 1997. That would mean that, by the hearing date in 2009, he would have owned the property during the 12 years in which house prices increased significantly. In turn, that would mean that he would have made a large gain on the property so that when he sold it, CGT would be due from him. He would not have been able to make use of the principal private residence exemption since he had remained living in his own house. If, on the other hand, the transaction could be declared void, then the property had never been transferred to him, he did not own it now and so he would not be liable for any CGT when the property was eventually sold.

The court in Re Beaney had seemingly declared the transaction void. But Christopher Nugee QC pointed out that the judge in the earlier case had emphasised that it made no difference on the facts whether the transaction was void or voidable. Re Beaaey could not be taken as authority that lack of capacity made a lifetime transfer void.

Christopher Nugee QC found that he did not need to express a decided view about whether the gift here by Norman to Mark was void or voidable. Such a declaration was only required by the parties in their efforts to avoid tax. Holding the transaction as invalid due to incapacity and that it should consequently be set aside was enough to dispose of the case. But he reviewed contradictory English and Australian authorities. He preferred the argument from the Australian courts11 that lack of capacity made the gift voidable, as opposed to void. Being an equitable issue, a gift being voidable would enable the doctrine of laches to be applied if the innocent party took too long to apply to the court for a declaration that the document was voidable.

Glossary: Laches

The doctrine of laches (delay) applies where an equitable remedy is sought. It may prevent the innocent party from seeking their remedy if they have delayed too long in applying for it, after their right to pursue their remedy has arisen. This principle is discussed further in Chapter 1 (under equitable maxim (vii) that delay defeates equities) and in Chapter 12.

If laches applied, gifts such as those made here could be kept alive, notwithstanding the lack of the donor’s capacity, because the donor failed to take action to set the gift aside within a reasonable period of time. Tantalisingly, by expressing no firm view, the High Court left this consequence open as a possibility if such gifts were seen to be voidable, as opposed to being void.

The usual practice, if possible, is to avoid scenarios such as those found in Re Beaney and Re Sutton. An alternative mechanism exists under the Mental Health Act 1983 where someone suffering from mental incapacity can place their affairs under the control of the Court of Protection. A disposition of their property then requires the court’s permission for that disposition to be valid. In that manner, a person suffering from mental incapacity may have their affairs controlled so that there will be no questions raised if dispositions do have the permission of that court.

Capacity of the trustee[s]

Generally, anyone can be a trustee of a trust provided they are 18 years of age or older and of sound mind. Section 34(2) of the Trustee Act 1925 provides that the maximum number of trustees of land at any one time is four. Where more than four people are named as trustees, the trustees will consist of the first four named only. As an exception, charitable or ecclesiastical trusts of land may have an unlimited number of trustees.12

Normally, it is good practice to have at least two trustees, so that one may both assist and keep a watchful eye over the other.

APPLYING THE LAW APPLYING THE LAW |

Having at least two trustees is useful if the trust property contains land. If the land is sold, the purchase money will be paid to the trustees and then the buyer can overreach the equitable interests of the beneficiaries under the trust.13 That means that the buyer will buy the land free from the trust, which is his objective. Overreaching the beneficial interests can only occur provided that there are at least two trustees of the trust or the trust is managed by a trust corporation.

Children as trustees

It appears that a child cannot be deliberately appointed to be a trustee, under s 20 of the Law of Property Act 1925. This section provides that:

The appointment of an infant to be a trustee in relation to any settlement or trust shall be void, but without prejudice to the power to appoint a new trustee to fill the vacancy.