Trusts of the Family Home

Chapter 14

Trusts of the Family Home

Chapter Contents

The Leading Case Today: Lloyds Bank v Rosset

Quantification of the Equitable Interest

This chapter concerns equity’s treatment of the family home and when one party may claim that they are entitled to a share in that home because they are the beneficiary of a trust even though they do not also own the legal estate. This is a modern application of the law of trusts. This chapter therefore builds upon your knowledge of resulting and constructive trusts, which are discussed in Chapter 3. You are advised to re-read Chapter 3 if you are unfamiliar with such trusts before progressing to the rest of this chapter.

As You Read

Look out for the following matters:

that this area can be broken down into two broad questions: can a trust be established and, if so, what shares are the parties to be treated as owning in equity? and

that this area can be broken down into two broad questions: can a trust be established and, if so, what shares are the parties to be treated as owning in equity? and

that equity traditionally used the resulting trust to establish and quantify the shares owned by the parties but over the last 15 years, there has been a shift in emphasis to make more use of the constructive trust.

that equity traditionally used the resulting trust to establish and quantify the shares owned by the parties but over the last 15 years, there has been a shift in emphasis to make more use of the constructive trust.

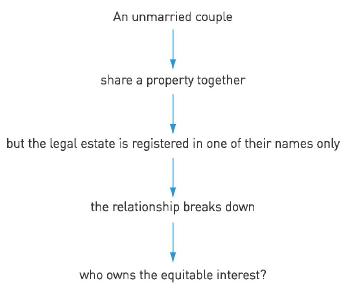

The Typical Scenario

The typical scenario involves a home being bought in one of the party’s sole names following which, at some later point, the parties‘ relationship breaks down. At that stage, to claim a beneficial share in the property, the non-owning party of the legal estate must rely on equity to intervene: their claim is based on the argument that their partner held the legal estate on trust for the two of them together. The non-owning party’s position may be summed up in Figure 14.1.

The establishment and quantification of an interest in the family home by using the law of trusts applies nowadays only to unmarried couples. From 1973, the Matrimonial Causes Act has given the court a wide discretion to make a property adjustment order (which will alter a couple’s beneficial interest in their home) on a divorce, provided the couple were married on or after the date the Act came into force. 1 No such power exists for the court when an unmarried couple’s relationship ends and whether the non-legally owning party may claim a beneficial interest in the family home is regulated by the law of trusts.

The relationship with the rules of formality

As discussed in Chapter 4, s 53(1)(b) of the Law of Property Act 1925 provides that any declaration of a trust concerning land must be evidenced in writing and signed by a person who is able to declare the trust. The usual difficulty in dealing with an unmarried couple’s rights to their home is that they will not have fulfilled the requirements of s 53(1) (b) when they purchased the property. Prima facie, it appears therefore that there can be no valid declaration of trust and the legal owner must also be the sole beneficial owner.

Fortunately, s 53(2) of the Law of Property Act 1925 comes to the rescue of the non-legal owner. If the non-l egal owner can establish a resulting or constructive trust in their favour, s 53(2) proves that such trusts need not be evidenced in writing.

Case law pre-Lloyds Bank v Rosset

The leading case on this area of law today is the 1990 decision of the House of Lords in Lloyds Bank v Rosset.2 To understand that decision, however, it is important to consider certain key decisions of the superior courts before then.The first occasion in modern times that the House of Lords had to consider a claim for a beneficial interest under a trust of a family home where the legal title had been vested solely in one party’s name was Pettitt v Pettitt.3

Harold Pettitt and his wife, Hilda, were married4 in 1952. They lived in a house which they had built themselves, called ‘Tinker’s Cottage’, in Bexhill-on-Sea, Sussex. They had been able to fund the building of the property by selling their only previous matrimonial home, which had been given to Hilda by her grandmother. Tinker’s Cottage was bought in Hilda’s name only. Their relationship broke down and Hilda moved out of the house.

Harold applied for a declaration from the court that he had an equitable interest in Tinker’s Cottage. His claim was based on the fact that he had undertaken work on Tinker’s Cottage which had enhanced its market value by, he estimated, £1,000. He said that s 17 of the Married Women’s Property Act 1882 gave the court the discretion to override and vary any existing rights in property and to regulate the parties‘ equitable ownership in whatever way the court thought fit.

The County Court registrar and the Court of Appeal both agreed that Harold had an equitable interest in the property. They agreed that his equitable interest was worth £300. Hilda appealed to the House of Lords.

The House of Lords held that Harold had no equitable interest in the cottage. Their Lordships held that s 17 of the Married Women’s Property Act 1882 should be narrowly construed. It could not have been Parliament’s intention to give a judge carte blanche to vary parties’ existing property rights. Such would create uncertainty in the law. Parties’ equitable rights had to be settled by means of established principles of trusts law. Unfortunately, the members of the House of Lords could not agree on one uniform set of established principles.

On the facts, he was not willing to hold that Harold had acquired an interest in Tinker’s Cottage. The improvements he had carried out were too temporary in nature to acquire an equitable interest in the property. The improvements essentially had to be of either a capital or recurring nature to lead to the acquisition of an equitable interest.

Lord Upjohn held that the equitable ownership of property had to depend on the agreement of the parties at the time they acquired the property. That meant looking at the conveyance (or ‘transfer’ document nowadays) under which the parties bought the property. If the transfer spelt out who was to own the equitable interest, that was the end of the matter, unless fraud or mistake could be found.

If the transfer was silent as to equitable ownership, Lord Upjohn thought that the court might be able to ‘draw an inference as to their intentions [as to equitable ownership] from their conduct’.5 Such conduct could only be at the time the property was acquired and not afterwards. If no such evidence was forthcoming, the court could apply legal presumptions:

[a] if the legal title to the property was vested in one party’s name only, that party will also own all of the equitable interest, even if the property was to be used for the benefit of both parties during their marriage;

[b] if the legal title was vested in two parties‘ joint names, both parties would own the equitable interest. Prima facie, those parties would hold the equitable interest as joint tenants (hence equally) but normally this would not be the case. Usually, the doctrine of the resulting trust would apply which would mean that both parties held the equitable interest in proportion to their contributions to the purchase price; but

[c] if both parties had contributed towards the purchase price, whether or not the legal title was vested in their joint names or solely in one party’s name, their intention was that they intended to be joint equitable owners, due to the application of the resulting trust presumption.

As can be seen, Lord Upjohn relied heavily on the notion of the resulting trust.

Lord Upjohn rejected the notion that property could be bought by one person but owned as a ‘family asset’ which would give rise, due to it being acquired for use by the family, to other members of the family acquiring an equitable interest in that property. English law did not recognise ‘family assets’. Equitable interests should not be accidentally created in favour of spouses because property was allegedly intended to be used as a family asset. More was needed than this to create an equitable interest in property: what was needed was an agreement between the spouses that they would share the equitable ownership.

Here there was no agreement that Harold and Hilda should share the property between them. Nor could one be inferred by their conduct at the time the land for Tinker’s Cottage was purchased.

Pettitt v Pettitt was considered by the House of Lords just over a year later in Gissing v Gissing.6

Raymond Gissing married Violet in 1935. In 1951, Raymond bought a home for them in Orpington, Kent. The majority of the purchase price of nearly £2,700 was paid by a mortgage and a loan from Raymond’s employer. Raymond paid the small balance due and the legal costs. The legal title to the house was transferred to him alone. During their time living in the house, Raymond paid the mortgage. Violet spent £200 on furniture and remedial work on their lawn. In 1961, the parties‘ relationship broke down and Raymond left the matrimonial home. Violet applied to the court for a declaration that she had an equitable interest in the house. Her claim was on the basis that her indirect contributions to the property should be reflected in a half-share of the house. She effectively said that it was due to her contributions that Raymond was able to work and be paid a sufficient sum to purchase the property intially and then pay the mortgage instalments.

The trial judge held that Violet had no equitable interest in the property. By majority, the Court of Appeal reversed this decision. Raymond appealed to the House of Lords. The House of Lords restored the trial judge’s decision and held that the equitable interest in the house belonged solely to Raymond.

Lord Diplock (who had also been in Pettitt v Pettitt) explained that the principle behind the recognition of an equitable interest by a non-legal owner was that the law of trusts was seeking to give effect to an implied trust created by the parties:

in connection with the acquisition by the trustee of a legal estate in land, whenever the trustee has so conducted himself that it would be inequitable to allow him to deny to the [beneficiary] a beneficial interest in the land acquired.7

Such a trust would be recognised because the court could infer — based on the evidence — that there was a common intention by the parties to share the property in equity. Lord Diplock accepted that he had probably been wrong in Pettitt v Pettitt to say that a trust could be imputed (imposed) onto the situtation. The trust could be inferred by one of two methods:

[a]where the parties had come to an express agreement to share the equitable interest. The express agreement had to contain an obligation on the non-legal owning spouse to act on it by contributing to the purchase price of the property, or paying the instalments under the mortgage. If there was no such obligation on the spouse, she would be a volunteer and equity would, of course, not assist a volunteer; or

[b]where the conduct of the legal owner had induced the non-legal owner to act to her detriment in the belief that she would obtain an equitable interest in the property.

If a wife used part of her earnings to pay joint household bills that otherwise the husband would have to pay, which enabled him to pay the mortgage instalments, that would be corroborative of a common intention to share the equitable ownership of the property.

In terms of valuing a contribution to the purchase price, the resulting trust mechanism could be used: the non-l egal owner would therefore be entitled to a share in the property in proportion to the amount originally contributed towards its purchase or subsequently paid in mortgage instalments. Both contributions went towards acquiring the property itself and therefore entitled the contributor to a share in it.

Summary of Pettitt v Pettitt and Gissing v Gissing

In both Pettitt v Pettitt and Gissing v Gissing, members of the House of Lords laid down a fairly narrow test for recognising that a non-legal owning spouse should be entitled to an equitable interest in the property. The key is that there had to be a common intention, possessed by the parties, that they should share the property in equity. In turn, that common intention could be evidenced by an agreement or by detrimental reliance by the non-legally owning party.

Developments by Lord Denning MR …

At first glance, a more generous result appears to have been reached for the non-legally owning spouse by Lord Denning MR in the Court of Appeal’s decision in Eves v Eves.8

Janet Eves met Stuart Eves when she was 19. They moved into a house together in Romford, Essex. They were not married, although Janet changed her surname to Stuart’s. The house was bought solely by Stuart — partly by the proceeds of his former home and partly by a mortgage in his name alone. Stuart told Janet that he would have put the legal title into their joint names but he could not as Janet was under 21. He later admitted this was a lie and that he never intended the property to be in their joint names.

After moving in, Janet did a lot of heavy work to the property by, for example, breaking up concrete using a 14lb sledgehammer and helping to construct a new shed. She and Stuart had two children. Then, four years after meeting, Stuart told Janet that he intended to marry another woman, Gloria. Janet applied for a share of the property, even though the legal title was solely owned by Stuart. The Court of Appeal unanimously held that Stuart held the property on trust for himself and Janet, but the members of the court did so for different reasons.

Lord Denning MR quoted Lord Diplock in Gissing v Gissing, focusing on Lord Diplock’s assertion that an implied trust could be imposed ‘whenever the trustee has so conducted himself that it would be inequitable to allow him to deny [the beneficiary] a beneficial interest’. He said the imposition of a constructive trust to the facts in the case before him showed that ‘[e]quity is not past the age of child bearing’9 to help a claimant such as Janet. He also quoted10 his own earlier judgment in Cooke v Head11 that:

whenever two parties by their joint efforts acquire property to be used for their joint benefit, the courts may impose or impute a constructive or resulting trust.

The difficulty with Lord Denning MR’s judgment is not in the result that was reached, but in that it seems to recognise the concept of a ‘family asset’ rejected by Lord Upjohn in Pettitt v Pettitt. In addition, Lord Denning MR sought to go further than a constructive trust had gone previously. Prior to this case, constructive trusts had been recognised by the courts as arising from particular facts; Denning wanted to go further by imposing — or imputing — a constructive trust on particular facts, effectively as a measure of doing justice between the parties. This was part of his greater scheme to develop the remedial constructive trust in English law which would have used the constructive trust as a proactive remedy, as opposed to it being used reactively to recognise a party’s legitimate claim.12 The imputation of a constructive trust had been rejected by the majority in Pettitt v Pettitt and by its only proponent in that case, Lord Diplock, in Gissing v Gissing.

Brightman J (with whom Browne LJ agreed) was of the same view that Janet should be awarded a quarter share of the house, but for more conventional reasons than Lord Denning MR. He focused on Stuart’s lie that he would have put the legal title into their joint names but could not as Janet was under 21. He said that such lie gave a ‘clear inference’13 that she was intended to have an interest in the property. That could be seen to be agreement to share the property. Brightman J said that, without more, that agreement would be a voluntary declaration of trust. Equity would not help Janet as she would be a volunteer. But there was more here: the agreement was that Janet would gain a share in the property provided she contributed in labour towards the acquisition of the house. There was little reason to suppose that Janet would have undertaken such heavy work in the property unless she was to acquire an equitable interest.

Brightman J and Browne LJ’s reasoning was more consistent with the jurisprudence expressed by the House of Lords in Pettitt v Pettitt and Gissing v Gissing. Stuart and Janet could be said to have made an agreement that she would be entitled to a beneficial share of the property. She acted (significantly) to her detriment on that agreement. Lord Denning MR was, not for the first time, seeking to develop equity on the principled basis of justice in the case, whilst giving little time to certainty. This sounds attractive but it might, for instance, be difficult to judge in successive cases whether property had been acquired by two people for their joint benefit. It is far preferable to find either an agreement between the parties or particular conduct by the legal owner to recognise that a trust should be inferred between the parties. In that way, each case may be evidence-led, instead of being subject to judicial whim.

ANALYSING THE LAW ANALYSING THE LAW |

Do you think there was really an agreement between Janet and Stuart Eves to share their house in equity? Was there, in fact, no agreement as he had deliberately set out not to be a joint legal owner with her? Do you find the majority’s view in the Court of Appeal convincing?

It was partly due to Lord Denning MR’s attempt to develop equity to recognise jointly acquired property that led to the House of Lords restating when a trust might be imputed in the key decision in Lloyds Bank v Rosset.14

The Leading Case Today: Lloyds Bank v Rosset

A farmhouse in Thanet, Kent was purchased by Mr Rosset and he was registered as the sole legal owner. The house was bought partly with the aid of a mortgage from Lloyds Bank. After his marriage to his wife broke down, the bank claimed possession of the property to pay off his overdraft. Mrs Rosset resisted the claim. She argued that her husband held the property on trust for them both in equity. The trial judge and the Court of Appeal held that Mr Rosset held the property on trust for them both, but that her interest could not override the bank’s mortgage as it was created after the bank’s mortgage had been entered into.

Mrs Rosset’s claim was that she and her husband had expressly agreed that the property was to be jointly owned and that, acting to her detriment, she had made a significant contribution towards acquiring the property by supervising extensive renovation works to make the farmhouse inhabitable.

In giving the only substantive opinion of the House of Lords, Lord Bridge drew a distinction between (i) sharing occupation and (ii) sharing the ownership of the asset of the matrimonial home. The former would be quite natural in a relationship. But it could not ‘throw any light’15 upon the latter, which was quite a separate issue.

Lord Bridge held that Mrs Rosset’s conduct was not of a type that could give rise to the acquisition of an equitable interest in the property. She had merely helped out with the renovation works. Those were entirely natural acts for a spouse to undertake when a dilapidated house had been purchased. The actions were not sufficient detrimental conduct which could support any arrangement that she should be entitled to an equitable interest in the property.

Lord Bridge held that it was a constructive trust that the non-legally owning party sought to establish. He also recognised that guidance needed to be given as to when that trust could be recognised in this type of situation. He said it could arise on either one of two occasions:

[a] When there is — prior to acquiring the property or exceptionally afterwards — an agreement between the parties that they would share the equitable interest in it. That could only be based on express discussions. But those discussions could be ‘imperfectly remembered’16 and their terms ‘imprecise’.17 In addition, the claiming partner would have to show that they acted to their detriment or ‘signficantly’18 altered their position to create a constructive trust or a claim in proprietary estoppel. There was no evidence of such an agreement between the parties on the facts of the case itself; or

[b] when there is no evidence of any express agreement, a constructive trust could be acknowledged by the court based on the parties‘ common intention to share the property. In this scenario, Lord Bridge said that only ’direct contributions‘ to the purchase price of the property — initially when the property was bought or later by paying mortgage instalments — would be acceptable as the common intention relied upon by the non-l egally owning party. Mrs Rosset made no such direct contributions towards the purchase price of the property.

Lord Bridge said that both Pettitt v Pettitt and Gissing v Gissing were examples of his second category of constructive trust. He approved of Eves v Eves19 as an example of a constructive trust falling in the first category.

Whilst Lord Bridge’s first type of constructive trust is clear, it must be questioned as to how appropriate it is to infer a trust on an alleged express agreement between two parties who probably gave little thought to sharing the beneficial interest in their home at a time when their relationship was new. As Waite J said in Hammond v Mitchell:20

the tenderest exchanges of a common law courtship may assume an unforeseen significance many years later when they are brought under equity’s microscope and subjected to an analysis under which many thousands of pounds of value may be liable to turn on fine questions as to whether the relevant words were spoken in earnest or in dalliance and with or without representational intent.

Lord Bridge distinguished between the type of detrimental conduct needed by a claimant in both cases. The detrimental conduct needed to establish a constructive trust in his first category was less than that needed in his second category. Janet Eves, for example, had been able to establish a trust in her favour due to the heavy DIY work she had undertaken. That was because she could demonstrate that there had existed an express agreement for her and Stuart to share the property beneficially. Her heavy DIY work would not have been sufficient conduct to establish a constructive trust of the second category, in the absence of any express agreement. She would have needed to show direct financial contribution to the acquisition of the property, either initially, or by making mortgage instalment payments.

Key Learning Point

A constructive trust of the home can only be acquired by one of two methods:

[a]express agreement + some detrimental reliance. This will now be referred to as a ‘Rosset category 1 trust’; or

[a]the parties’ conduct but such conduct can only be making (a) direct contributions to the purchase price of the property or (b) mortgage payments. This will now be referred to as a ‘Rosset category 2 trust’.

This issue has recently returned to the Supreme Court in Jones v Kernott.21 The facts of Jones v Kernott concerned the right approach that the court should take when quantifying beneficial ownership when the parties had not done so for themselves when they purchased the property. Unfortunately, very little was said about the establishment of the trust and the decision in Lloyds Bank v Rosset was not mentioned at all. Rosset remains the leading authority as to when a trust of the family home may be established and it is now time to turn to when the courts have held that such a trust has been created.

Examples of Rosset category 1 trusts

In his opinion in Lloyds Bank v Rosset, Lord Bridge expressly approved22 the earlier cases of Eves v Eves and Grant v Edwards as examples of where a trust would be recognised by the courts in his first category: where the parties made an express agreement to share the beneficial interest and it had been acted upon by the non-l egal owner to their detriment. These are sometimes referred to as the ‘excuse’ cases: where the court found an intention to share the equitable interest because the legal owner used a fairly flimsy excuse not to put the legal title into joint names.

The ‘excuse’ cases …

Eves v Eves has already been considered. There the legal interest in the house was owned by Stuart at law, but Janet was able to show that he held it on trust for them both in equity. This was based on his promise to her that they would both have owned the legal interest were she not under 21. In Lloyds Bank v Rosset, Lord Bridge viewed that promise as a clear indication by Stuart to Janet that the house would be owned by them jointly. Janet had acted to her detriment on that promise by undertaking the significant renovation works to the property.

Not dissimilar circumstances arose in Grant v Edwards. Linda Grant met George Edwards in the late 1960s and they moved in with each other. Both of their previous marriages had broken down and each was in the process of obtaining a divorce from their former spouses. They decided to purchase a house together in London, but the legal interest was registered in the name of George with his brother, Arthur. This was done so that Arthur’s income could be taken into account in obtaining a mortgage to purchase the house. George told Linda that she should not own the house as that would prejudice any settlement she was to obtain from her former husband in their divorce proceedings. This was a lie. George never had any intention of ensuring that Linda also became an owner of the house. After they had moved in together, Linda made contributions towards the general household expenses and to the raising of the children.

The Court of Appeal held that there was a common intention to share the property beneficially. This could be inferred from the excuse given by George to Linda as to why the legal interest in the property would not be registered in their joint names. Nourse LJ said that George only used the excuse that putting the house into their joint names would prejudice Linda’s divorce settlement for the very reason that he had an intention that they should share the ownership of it. Linda had acted to her detriment on the agreement that they had reached by making significant contributions to the household expenses and bringing up the children. Her contributions enabled George to make the mortgage payments.

Nourse LJ questioned the type of conduct that was needed by the non-owning party to establish an equitable interest under this category of trust. He said it had to be, ‘conduct on which the woman could not reasonably have been expected to embark unless she was to have an interest in the house’.23

That meant that there was a certain basic ‘level’ of conduct that a non-legally owning party would have to show before the court could infer a constructive trust in their favour. There had to be some connection between the conduct they undertook and the point that they only undertook it because they expected to acquire an equitable interest in the property. Janet wielding a 14lb sledgehammer in Eves v Eves was an example cited by Nourse LJ: she only undertook such work because it could objectively be said that she intended to acquire an equitable interest in the property. On the other hand, Nourse LJ said that merely moving in with the legal owner would not amount to conduct required to establish an equitable interest: the law was ‘not so cynical as to infer that a woman will only go to live with a man to whom she is not married if she understands that she is to have an interest in their home’.24

It is suggested that it is hard to disagree with the eventual decisions of the Court of Appeal in both Eves v Eves and Grant v Edwards. Both non-legally owning spouses had been misled by their partners and both had made significant contributions to their households. On first principles, it might be thought of as ‘fair’ that both Janet Eves and Linda Grant should be seen to enjoy equitable interests in their houses. But, it is also suggested that it is hard to see evidence of direct agreements between them and their respective partners to share their properties beneficially.25 In both cases, the Court of Appeal found evidence of agreement on the basis that their partners misled them only because they realised that they intended to share the property.Yet it is equally plausible to argue that there was no evidence of an agreement to share the properties at all: that was the reason why the excuses were given to Janet and Linda. Hammond v Mitchell,26 however, is one of the very few examples of cases in this area that does show evidence of a clear agreement to share the equitable ownership of the property.

A clear agreement case …

Tom Hammond met Vicky Mitchell in 1977. They moved into a bungalow in Essex together in 1979. The legal title to the property was registered in Tom’s sole name. He was in the process of obtaining a divorce, but whilst they were looking at the bungalow before buying it, he said to Vicky, ‘[d]on’t worry about the future because when we are married it will be half yours anyway and I’ll always look after you’.27

In fact, the parties never did marry although Tom did obtain a divorce from his wife. Throughout their relationship, he developed his business of buying and selling household goods with her support. She would, for example, place advertisements, sell goods on his behalf and act as his secretary. His business expanded to buying a business in Spain and both Tom, Vicky and their children went to live in Spain for two years, during which she helped out running the Spanish business. A house in Valencia was bought, again with Tom as the sole legal owner. Their relationship finally broke down in 1989. Vicky brought a claim for a beneficial interest in the bungalow and the house in Spain.