Leases and Licences

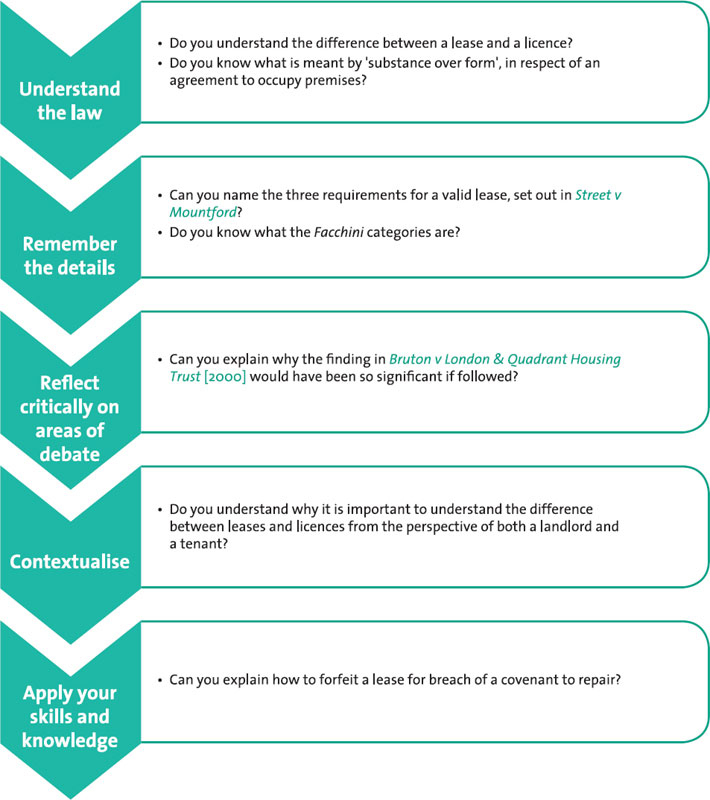

Revision objectives

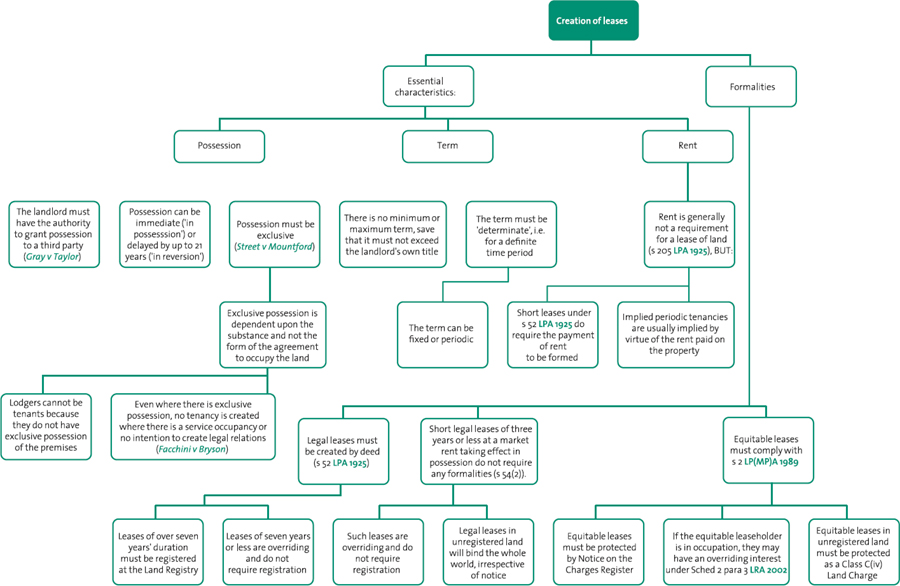

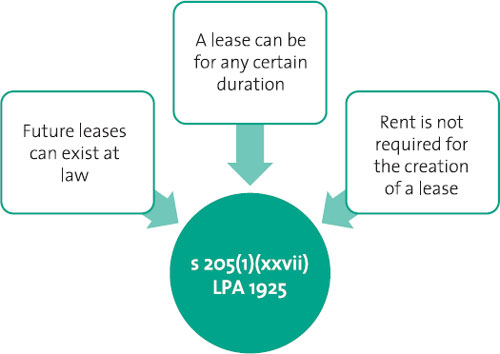

The leasehold estate or ‘term of years absolute’ is one of the two legal estates in land (s 1(2) LPA 1925). In layman’s terms, a lease is where a landlord allows a tenant to possess property belonging to the landlord for a fixed or certain period of time. Leases are also given statutory definition under s 205(1)(xxvii) LPA 1925. There are three main points to note from the statute:

1. A lease can take effect either immediately (‘in possession’) or at some specified point in the future (‘in reversion’), so long as it commences within 21 years of its creation. Thus, it is possible to have a future leasehold interest.

2. There is no maximum or minimum period given for the duration of a lease, as long as it is certain. For this reason, a lease for the duration of somebody’s life cannot exist at law, because the length of such a lease cannot be predetermined.

3. Perhaps surprisingly, the payment of rent is not required for the creation of a leasehold interest in land.

Types of lease

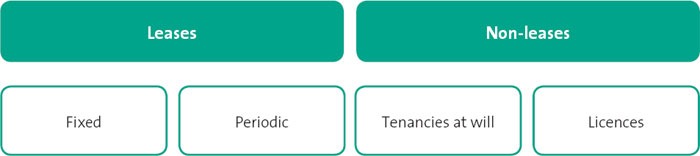

Leases can be either:

Fixed | – | granted for a fixed term, for example, ten years; or |

Periodic | – | granted for a shorter term (e.g. weekly, monthly or quarterly) that is renewed automatically until notice is given by either party. |

Tenancies at will are in fact not a type of lease at all, but a purely informal agreement between the parties to occupy the premises, determinable at any time by either party.

Leases and licences

Licences are also purely personal agreements between two parties to occupy land. As such, they confer upon the licence holder no proprietary interest in the land: a licence cannot be sold or otherwise transferred to a third party; neither can it enjoy any security of tenure. The licensee is on the land effectively at the whim of the landowner.

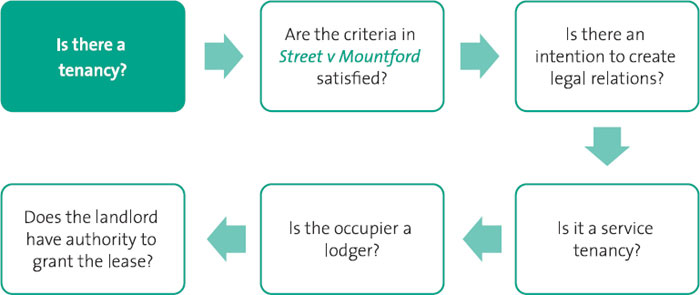

But if a person is occupying property, how can you tell whether they have a simple licence or a lease? There are three basic components of a lease, set out in Street v Mountford [1985]. These are:

exclusive possession;

exclusive possession;

for a determinate term; and

for a determinate term; and

at a rent.

at a rent.

Rent

As we have seen from the definition of a leasehold interest given in s 205 LPA 1925, technically speaking rent is not a formal requirement of a valid legal lease. The Court of Appeal in Ashburn Anstalt v Arnold [1989] Ch 1 confirmed that the listing of rent in Street v Mountford as a prerequisite for a valid lease does not preclude a lease under which no rent is payable from being valid.

Aim Higher

Although rent is not a prerequisite of a leasehold interest, it is a requirement for the creation of a legal lease of three years or less, which must be for ‘the best rent which can reasonably be obtained without taking a fine’ (s 54(2) LPA 1925). See Feedback on putting it into practice at the end of the chapter for an explanation of how this works in practice.

Case precedent – Lace v Chantler [1944] KB 36

Facts: A lease ‘for the duration of the war’ was held unable to form the basis of a legal lease, because no one could say for how long the war (the Second World War, in this case) was going to continue.

Principle: In order to create a valid lease, there must be a determinate term.

Application: Use the facts of this case as an example of what will constitute an indeterminate term.

Again, as per the statutory definition this means the lease must start on a specified date and end on either a specified date or a date calculable at the commencement of the term.

Up for Debate

In Berrisford v Mexfield [2011] 1 WLR 1091, the claimant occupied the property on a monthly tenancy which the housing association could not bring to an end unless the claimant breached one of the terms of the agreement. The Supreme Court found that, whilst the term of the agreement was therefore indeterminable, a tenancy had nevertheless been created on the basis that it would be inequitable to find otherwise. The ruling has been subject to a great deal of debate as, if followed, the requirement for a term certain would effectively be nullified; however, the suggestion of academic commentators is that the ruling was intended to apply to social housing cases only and not in a wider context. See Pawlowski, M, ‘Uncertainty of term – orthodoxy side-stepped in favour of a just result’, L&T Review 2012, 16(1), 16–22 and Hunter, C & Cowan, D, ‘The future of housing co-operatives: Mexfield and beyond’, JHL 2012, 15(2), 26–32.

Exclusive possession

Exclusive possession is the right to exclude all others from the property, including the landlord.

Case precedent – AG Securities v Vaughan [1990] 1 AC 417

Facts: There were four flat sharers, each being granted at different times and on different terms a six-month licence to occupy the flat in conjunction with three others at the landlord’s discretion, and each paying different amounts for the use of their room within the flat. Held: These were four genuine and separate licences and did not together constitute a jointly shared lease of the property.

Application: Use this case to illustrate what will constitute exclusive possession under Street v Mountford [1985].

Case precedent – Westminster City Council v Clarke [1992] 2 AC 288

Facts: The council ran a hostel for single homeless men with personality disorders or learning disabilities. The premises contained 31 rooms, each with a bed and limited cooking facilities. Each room was occupied under a licence agreement which specified that the occupant could be required to change rooms at any time or to share it with another person. The premises were overseen by a warden and a team of social workers, who were entitled to access the rooms at any time without notice in order to facilitate the occupants. Held: The agreements were licences as they did not grant exclusive possession to the occupiers.

Principle: In order to have a valid lease, the tenants must enjoy exclusive possession of the property.

Application: Compare the facts of this case against those in your own scenario to decide whether or not there is exclusive possession of the property in question.

It is the substance of the agreement (i.e. what the parties really agreed), and not the form (i.e. the label given to the agreement), that matters when proving exclusive possession.

‘If the agreement satisfied all the requirements of a tenancy, then the agreement produced a tenancy and the parties cannot alter the effect of the agreement by insisting that they only created a licence. The manufacture of a five-pronged implement for manual digging results in a fork even if the manufacturer, unfamiliar with the English language, insists that he intended to make and has made a spade.’

Lord Templeman, Street v Mountford [1985]

Facts: A couple rented a one-bedroom flat together under separate but identical ‘licence’ agreements. When the couple was shown around the flat they asked the landlord to provide a double bed, which he did. However, when it came to signing the agreements, the documentation stated that the couple did not have exclusive possession of the premises and that the licensor or anyone else of his choosing could use the rooms along with the couple. Held: There was a joint tenancy and not a licence. This was despite the description of the agreements as individual licences.

Principle: When proving exclusive possession, it is the substance of the agreement and not the form that matters.

Application: Use this case to illustrate your point that a lease will be created wherever there is exclusive possession, regardless of the label that is given to the agreement.

Case precedent – Aslan v Murphy [1990] 1 WLR 766

Facts: The case considered three purported licence agreements, each of which contained terms that the court considered to be a pretence and therefore constituted a tenancy. In particular in one case, the occupier was required to vacate the room entirely between 10.30 am and 12 pm each day; and in another, the landlord retained a key to the premises to provide services to the tenant which were never provided.

Principle: When proving exclusive possession, it is the substance of the agreement and not the form that matters.

Application: Use this case to support your argument that sham agreements will not avoid the creation of a tenancy.

The Facchini categories

There are three situations in which no tenancy will be created, even where the criteria set out in Street v Mountford are satisfied. These are:

1. where there is no intention to create legal relations;

2. service occupancies; and

3. lodgers.

Facchini v Bryson [1952] 1 TLR 1386

No intention to create legal relations

In certain situations (usually where there is a personal relationship between the parties, but also in the case of acts of kindness or charity), there will clearly be no intention to create a legal relationship and thus no tenancy will be created, irrespective of the nature of the letting.

Case precedent – Booker v Palmer [1942] 2 All ER 674

Facts: A landowner allowed his cottage to be used to house evacuees during the Second World War. Held: This was a simple act of generosity by the landowner and there had clearly been no intention to create legal relations. The evacuees were therefore occupying the cottage under a licence and not a tenancy.

Principle: No lease will be created in situations where there is no intention to create legal relations.

Application: Compare the facts of this case against your own to discover whether there is an intention to create a relationship of landlord and tenant.

Service occupancies

Where a person occupying property is required to do so in order to perform their duties as an employee, this will be classed as a service-occupancy and no tenancy will be created.

Case precedent – Norris v Checksfield [1991] 1 WLR 1241

Facts: A coach driver was granted a licence by his employer to live in a bungalow near to where he worked ‘for the better performance of his duties’. The driver paid £5 per week to live there. When the driver was later dismissed, he claimed the benefit of a tenancy over the bungalow. Held: This was a licence and therefore determinable without notice when the employee ceased to work for his employer.

Principle: No lease will be created where the occupancy is for the better performance of an employee’s duties.

Application: Use this case to illustrate what is meant by a service occupancy.

Lodgers

A lodger is someone who stays in the home of the landlord as a paying guest. Whilst the lodger will have a room of their own, therefore, the landlord will have unrestricted access to that room in order to clean the room, change the bed and provide the lodger with meals. Because of these attendant services, there will be no exclusive possession granted of the room and so the lodger will remain a licensee of premises (Marchant v Charters [1977] 1 WLR 1181).

Case precedent – Markou v Da Silvasesa [1986] 18 HLR 265

Facts: An agreement provided for services to be provided including a housekeeper, the provision of a telephone, the collection of rubbish and the provision and laundering of bed linen. Held: This was a licence, and not a tenancy.

Principle: A lodger cannot have a tenancy because they do not have exclusive possession of the premises.

Application: Use this case to support your argument that services provided amount to a lodging scenario under Facchini v Bryson.

Authority to grant the lease

The landlord must have the legal authority to let the premises. This is particularly relevant in the case of leasehold property owners, who may be subject to covenants in their own lease not to sublet the premises, or not to sublet without the consent of the landlord.