Co-ownership

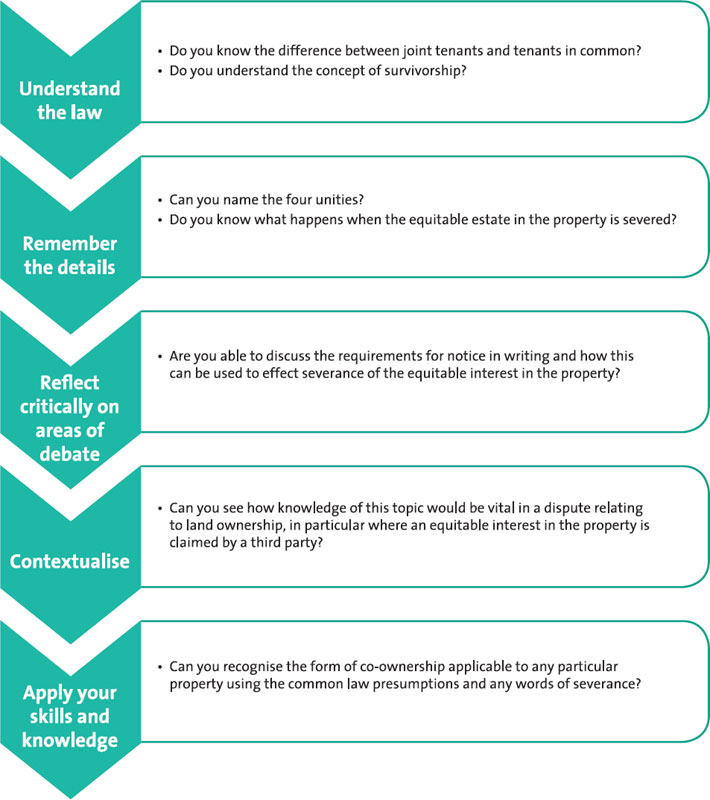

Revision objectives

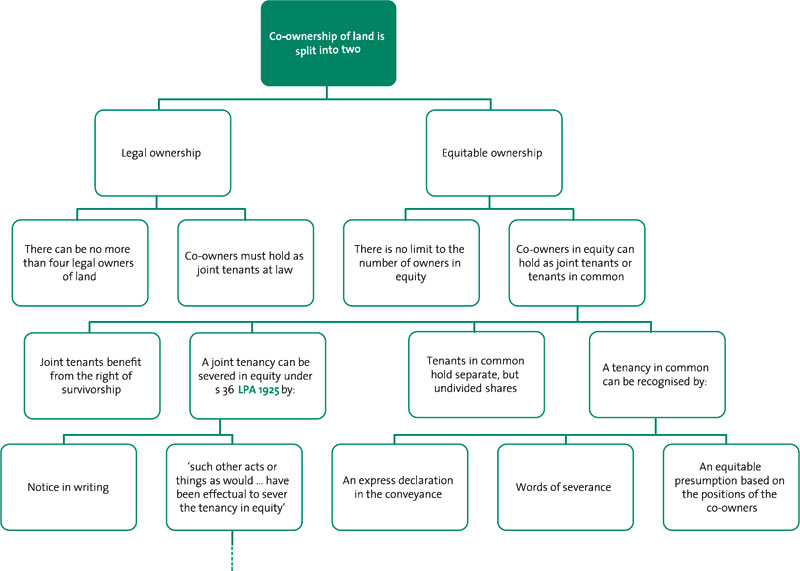

Land ownership can be separated into two constituent parts: legal ownership and equitable ownership. The legal owners hold the legal title to the property and so have the right to deal with the property at law, including the right to sell it. The equitable owners have the right to the benefit of the property, which they may receive by living in it, receiving rents from it and such like.

The way in which the legal and equitable interests in property are held bear some marked differences.

Ownership of the legal estate

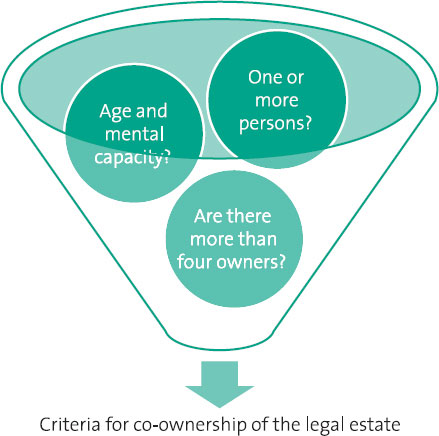

At law, an estate in land can be held by a single person (as sole proprietor), or by two or more people together (as co-owners).

Any person with the requisite mental capacity (as defined by the Mental Capacity Act 2005) can own an estate in land, provided they are over the age of 18 (s 1(6) LPA 1925). If they are under 18, the legal estate in the land must be held on trust for them in equity, until they reach the age of majority.

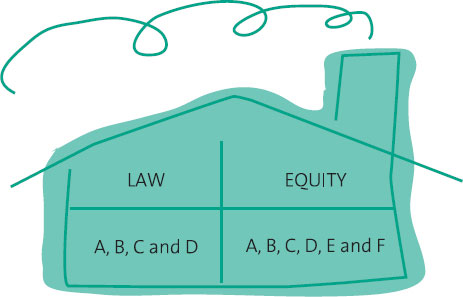

There can be no more than four owners of the legal estate (s 34(2) LPA 1925).

If there are more than four owners, the first four named on the deed of conveyance or transfer of the property who have the required legal and mental capacity, will become the owners of the property at law, holding the property on trust for themselves and the other co-owners named in the deed. The remaining co-owners will thus hold the property in equity only.

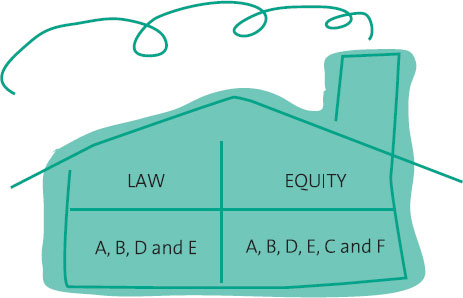

To give an example, if there are six persons named on the transfer deed (A, B, C, D, E and F), the first four named in the deed will become the legal owners, holding on trust for themselves and the fifth and sixth persons named in the deed.

If one of the persons named (say, in this case C) is under 18, then the first four named in order excluding the minor will become the legal owners, with the minor and the sixth remaining owners holding in equity.

Ownership of the equitable estate

The legal owners of the property hold the land on trust for those who have a beneficial interest in the property in equity. In the case of a sole proprietor who owns the whole of the legal and equitable interest, this is simple. However, a sole proprietor may also hold the legal estate on trust either for themselves and another in equity, or simply for a third party, with the legal owner having no equitable interest in the property at all.

In the case of co-owners, an automatic trust is imposed by statute, the legal owners holding the property on trust for themselves in equity by virtue of s 36 LPA 1925. Again, this is not to say that co-owners may not hold the property on trust for themselves and others, or for a third party with no equitable interest being retained for themselves.

Understanding: joint tenants and tenants in common

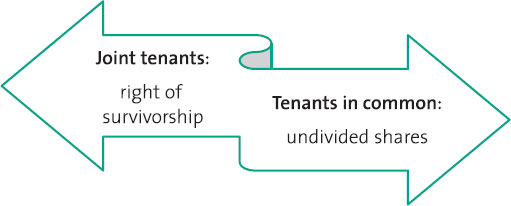

Whereas at law there is only one way of holding the legal estate, as ‘joint tenants’, in equity there are two different methods of holding the land, either as ‘joint tenants’, or as ‘tenants in common’.

As joint tenants, co-owners hold the whole of the property together as a joint, or group owner. They do not hold shares in it: they own the whole together. Imagine buying and owning a family dog – the family cannot physically divide it into sections – they simply own the dog as a whole, and share both in the responsibility and enjoyment of owning it as a family.

At law, there is no other way of co-owning property: all property is owned at law as joint tenants (s 1(6) LPA 1925).

Common Pitfalls

Do not confuse the reference to ‘tenants’ with a tenant of a lease. The word ‘tenant’ in this context is a derivative of the word ‘tenure’, and refers to the way in which the couple holds the legal estate in the land.

Because of the nature of joint tenancy as effectively a ‘group ownership’ of the whole, if one of the co-owners dies, there are no divisible shares in the property to be passed on to surviving relatives of the deceased co-owner. Instead, the property simply remains in ownership of the surviving joint tenants. It is only when the last surviving co-owner dies that the property will devolve to the survivor’s next of kin or other person specified in their will.

Tenants in common

Whilst joint tenants are seen as a group entity, owning the whole of the property together, tenants in common are viewed as separate individuals, owning the whole in ‘undivided shares’. This means that, unlike joint tenants, tenants in common are able to own a specified share of the property, the value of which they will recoup on its subsequent sale. So, for example, a couple may own a property in equal shares, but also proportionately in two thirds and one third, or in any other combination of figures.

There is no right of survivorship in the case of tenants in common; if one co-owner dies, their share of the property does not therefore automatically pass to their co-owner. Rather it passes either to their next of kin in the case of intestacy, or as specified under the terms of their will.

Points to remember about the division of land ownership

How can you tell whether co-owners are joint tenants or tenants in common?

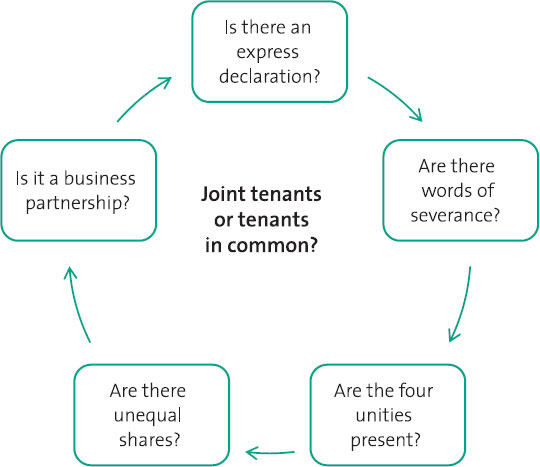

1. Look for an express declaration

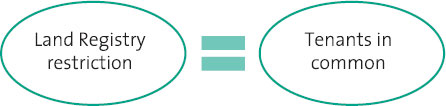

The first thing to look for is an express declaration by the parties as to how they intend to hold the property they are buying in equity. In unregistered land, the declaration will be found in the body of the conveyance; in registered land, if the property is to be held as tenants in common, the Land Registry will enter a restriction on the Proprietorship Register preventing the property from being sold by a sole proprietor of the land. There will be no such restriction where the co-owners are joint tenants.

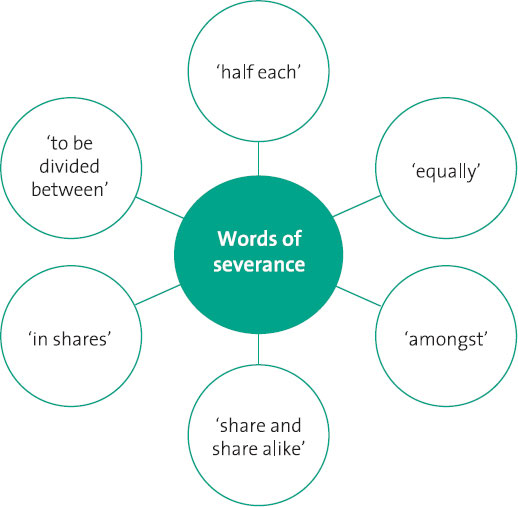

2. Words of severance

If the deed of transfer of the property does not specify how the co-owners are going to be holding their equitable interest in the property, it may still be possible to determine their position by the existence of ‘words of severance’ in the documentation. These are words that indicate a desire to hold the property in shares (and hence as tenants in common), rather than on the basis of a joint tenancy. Words of severance include:

3. Presumptions

If there is neither an express declaration nor words of severance in the transfer deed, it may still be possible to determine by looking at the wider context of how the co-owners intend to hold the property. This is because equity makes certain presumptions:

If the four unities are present, then the presumption is that the intention is to create a joint tenancy, rather than a tenancy in common (AG Securities v Vaughan (1988)).

If the four unities are present, then the presumption is that the intention is to create a joint tenancy, rather than a tenancy in common (AG Securities v Vaughan (1988)).

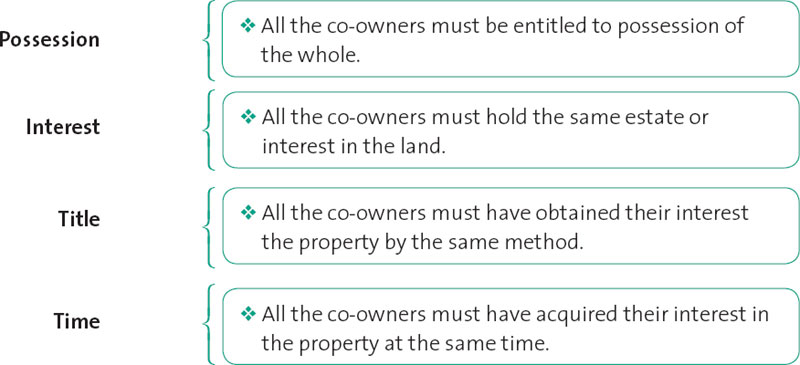

If any one of the unities is not present, the co-owners will be deemed to be holding the property in equity as tenants in common. The four unities are:

If co-owners provide the purchase money to buy the property in unequal shares, equity will presume that they intend to hold the property, not as joint tenants, but as tenants in common in proportion to their respective contributions to the purchase price (Bull v Bull [1955] 1 QB 234).

If co-owners provide the purchase money to buy the property in unequal shares, equity will presume that they intend to hold the property, not as joint tenants, but as tenants in common in proportion to their respective contributions to the purchase price (Bull v Bull [1955] 1 QB 234).

Aim Higher

It should be noted that these presumptions can be rebutted if there is an express declaration in the transfer deed; the law will uphold the written declaration of the parties above and beyond any natural presumption that may exist to the contrary (Pink v Lawrence (1978) 36 P&CR 98).

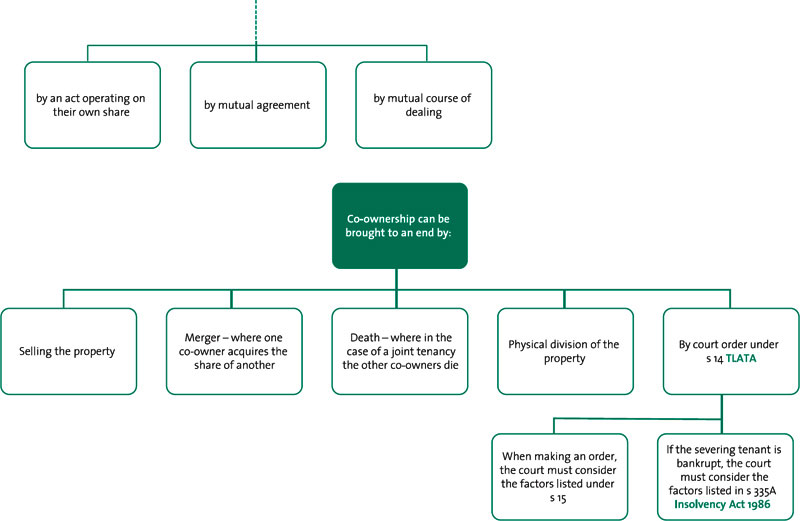

Severing the joint tenancy

Sometimes co-owners who buy property together as joint tenants may later wish to become tenants in common. The process through which they do this is known as ‘severance’.

Severance only applies to the equitable estate in the land: it cannot apply at law (s 36(2) LPA 1925).

Severance can only take place in equity.

According to s 36(2), the joint tenancy can be severed in in equity in one of two different ways – either:

by the giving of written notice to the other co-owners; or

by the giving of written notice to the other co-owners; or

by ‘such other acts or things as would, in the case of personal estate, have been effectual to sever the tenancy in equity’.

by ‘such other acts or things as would, in the case of personal estate, have been effectual to sever the tenancy in equity’.

Written notice under s 36(2) should be given to all of the other co-owners, if more than one, of the intention to sever, in order for severance to take effect in equity. The notice does not have to take any particular form; nor does it have to be signed, nor agreed by the other co-owners. As long as the notice is unequivocal and immediate in its effect, this will be enough to sever the tenancy.

Case precedent – Harris v Goddard [1983] 1 WLR 1203

Facts: A divorce petition served on a husband requesting ‘such order in relation to the property by way of transfer or settlement as should be just’ was held not to be effective notice of severance by the wife, because the wording of the petition merely asked the court to exercise its discretion in respect of the property at some future date; it did not show an immediate desire to sever.

Principle: Written notice to sever must be unequivocal and immediate in its effect.

Application: Compare the facts of this case with your own problem question scenario and use it to support your argument that a written notice either is or is not valid under the circumstances.

Although severance can be effected by notice in writing in any form, it is not possible to sever a joint tenancy by will.

Case precedent – Re Caines (deceased) [1978] 1 WLR 540

Facts: A notice of severance had been prepared but not served on the deceased’s wife. In lieu of this, the solicitors for the deceased sought to claim that the will itself was proof enough of effective severance by notice. Their claim failed.

Principle: It is not possible to sever a joint tenancy by will.

Application: Use this case to support your statement that severance cannot be achieved by will.

Up for Debate

Despite this, it may be possible to sever a joint tenancy in equity through the creation of mutual wills. In Re Wilford’s Estate (1879), LR 11 ChD 267, the court held that the creation of mutual wills by two sisters were effective in severing their beneficial interest in the property. The sisters had each made a mutual will purporting to leave their share in the property they jointly owned to the other for life, and then to their nieces after the death of the last surviving sister. The court held that, in making the mirror wills, the sisters showed a course of dealing which acknowledged their belief that they each had separate shares in the property that they could dispose of independently.

left at the last-known place of abode or business in the United Kingdom of the person to be served; or

left at the last-known place of abode or business in the United Kingdom of the person to be served; or

sent by post in a registered letter addressed to the person to be served.

sent by post in a registered letter addressed to the person to be served.

Provided that notice in writing has been served effectively on all the other joint tenants, then the joint tenancy will be severed and the co-owner will hold from the date of service their share of the tenancy as a tenant in common; the notice need not have been actually received to have been deemed served, under the terms of the Act.

Case precedent – Re 88 Berkeley Road, NW9 [1971] 2 WLR 307

Facts: Two ladies owned a house together as joint tenants in equity. Following the marriage of one lady, the other instructed her solicitors to sever the joint tenancy. The solicitors sent notice of severance in the post by recorded delivery, but it was received and signed for by the severing joint tenant. Held: The delivery of the notice by recorded mail was sufficient to effect severance of the equitable estate as between the two ladies under s 36(2).

Principle: Severance will be effective if the notice is sent by recorded delivery, even if the recipient never sees the notice.

Application: Compare the facts of this case with your own scenario and use it to support your argument that severance has been effectively served by notice.

Case precedent – Kinch v Bullard (1999) 1 WLR 423

Facts: A wife served notice by way of ordinary first class post on her husband of her wish to sever the joint tenancy on the matrimonial home. Before the husband read the notice, however, he was admitted to hospital with a heart attack. Realising that she would receive the house through the right of survivorship if the husband died without the joint tenancy having been severed, the wife destroyed the notice. The husband died a week later. However, the court held that the notice had nevertheless been effectively served because it had been delivered to his last-known place of residence.

Principle:

Again, in the case of business partnerships, equity will presume that the intention was not to hold the property as tenants in common (

Again, in the case of business partnerships, equity will presume that the intention was not to hold the property as tenants in common (