Estates and Interests in Land

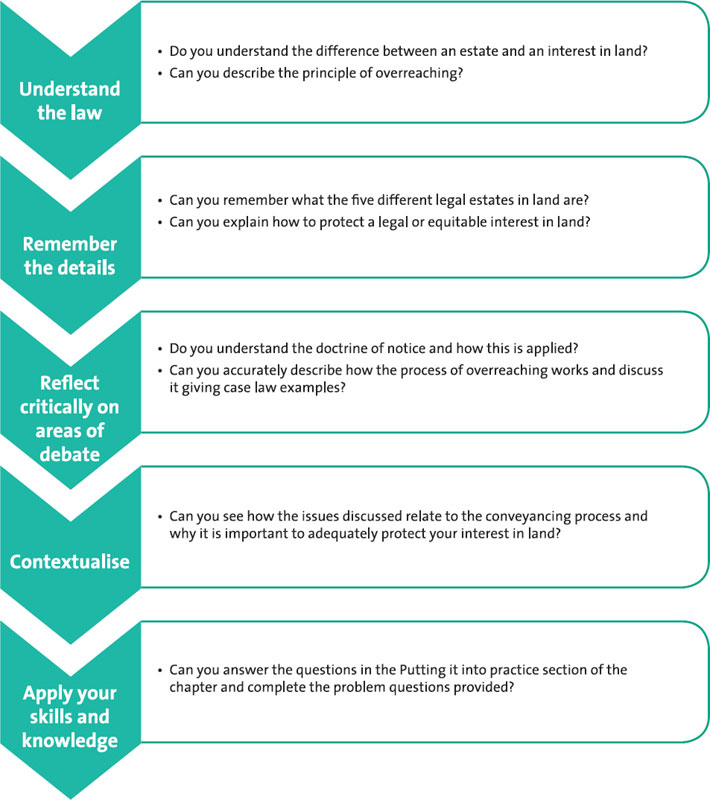

Revision objectives

In Chapter 1 you were introduced to the concepts of tenures and estates in land. This second chapter takes us a step further by introducing the various lesser rights that an individual may have over land, both legal and equitable, and how those rights may be discovered or protected. In particular you will be taking a look at unregistered (or ‘overriding’) interests in land, which are often the focus of exam questions. You will also be considering the concept of overreaching which, again, is a device that you will be expected to be able to understand and apply in an exam scenario.

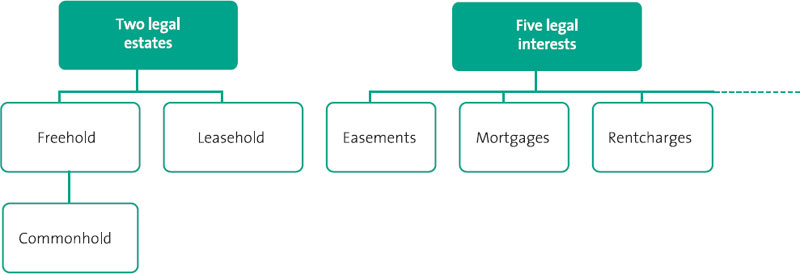

Understanding: estates in land

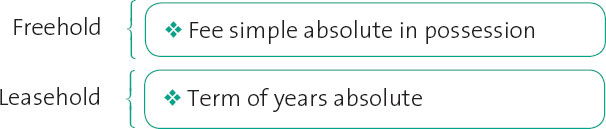

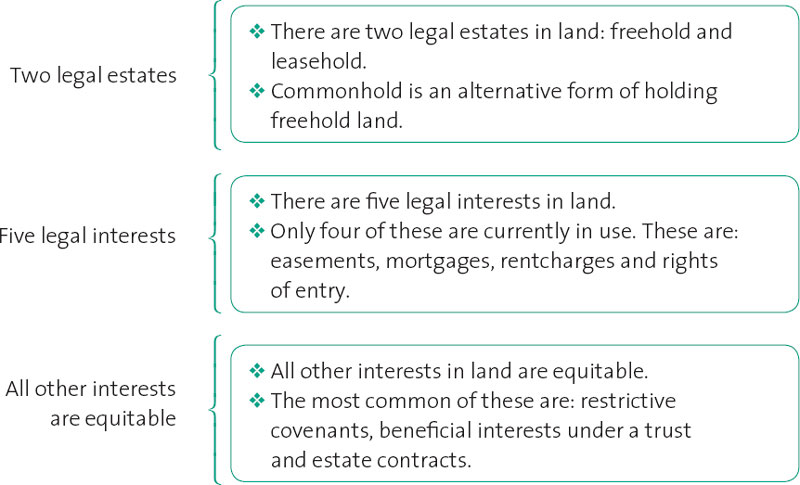

There are two legal estates in land: the ‘fee simple absolute in possession’ (or freehold) and the ‘term of years absolute’ (or leasehold).

Freehold

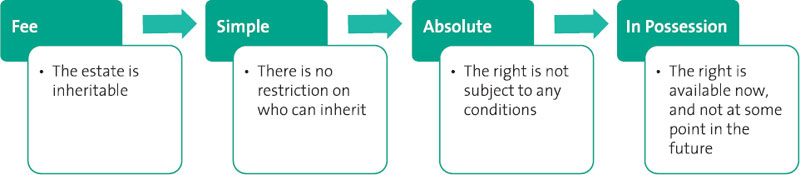

The formal term for the freehold estate, ‘fee simple absolute in possession’, can be broken down into smaller sections:

A freehold estate, therefore, is an inheritable estate in the land which exists in the present and which will continue for an unlimited period of time. The only reason this kind of estate will be brought to an end is where the owner dies without leaving anyone to inherit. In this case the land will be returned to the Crown, as absolute owner.

It should be noted that the term ‘in possession’ does not require actual physical possession of the property; under s 205(1)(xix) of the Act, if the freeholder is in receipt of rents or profits made from the land, this will be sufficient to denote ‘possession’ for legal purposes.

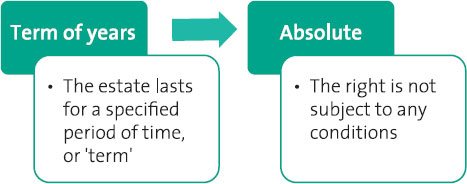

Leasehold

The leasehold, or ‘term of years absolute’, is more limited than the freehold, continuing only for a specified period of time, or ‘term of years’:

When the specified period comes to an end, the leasehold estate will cease and the land will be returned to the freehold owner of it. The nature of leasehold property is discussed in more detail in Chapter 7.

Aim Higher

Can you see what is missing from the statutory definition of the leasehold estate?

A leasehold estate in land does not have to take effect ‘in possession’. This means that it is possible to have the benefit of a lease that starts at some point in the future.

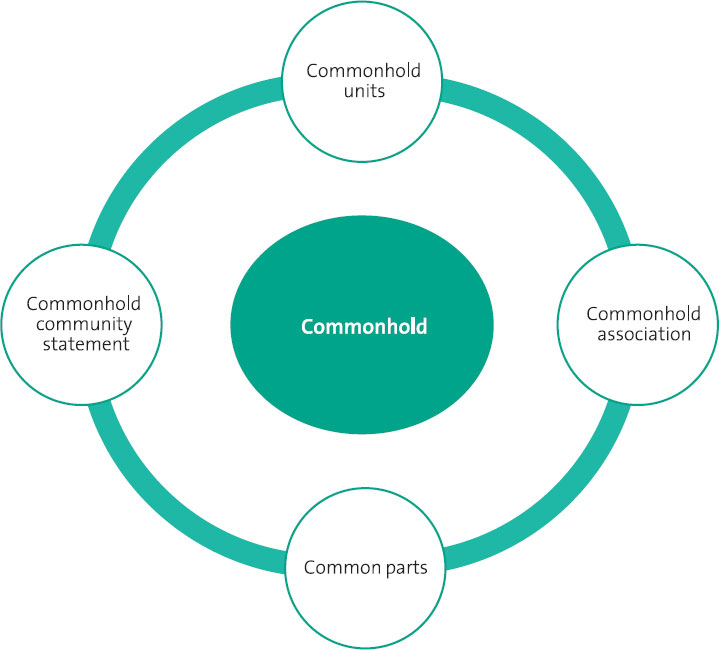

Commonhold

The Commonhold and Leasehold Reform Act 2002 created a new form of landholding, called commonhold.

The concept of commonhold land was created primarily to overcome difficulties faced by owners of leasehold property in enforcing covenants (that is promises to do, or not to do, something) against neighbouring properties, but it has not proved a popular device.

Commonhold should not be mistaken for another form of estate in land, however. In fact, it is simply an alternative method of holding freehold land. Anyone buying commonhold land is therefore buying the freehold in the property, but subject to the rules and regulations of the commonhold.

The features of commonhold can be summarised as follows:

Each separate property within the commonhold is called a commonhold ‘unit’. |

The shared or ‘common’ parts of the commonhold are owned by a commonhold association, who are in charge of the commonhold’s management and maintenance. |

Every unit holder is a member of the commonhold association so that all the unit holders share in the running of the common parts. |

The commonhold association abides by rules set out in a ‘commonhold community statement’. |

Unit holders pay a management or service charge to the commonhold association for the upkeep of the common parts. |

Understanding: interests in land

Introduction

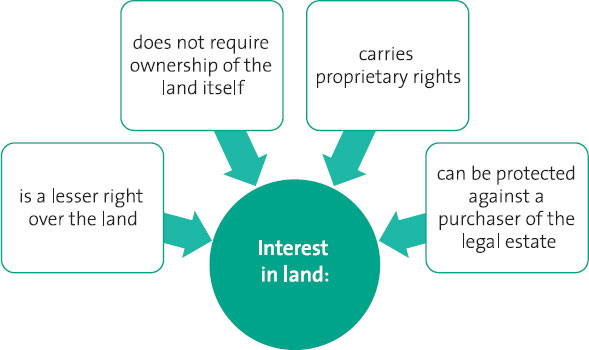

In addition to the two legal estates in land, it is also possible to have an interest in land. This is a lesser right over the land which falls short of possession.

Anyone can own an interest in land.

It is not always necessary to own land to have an interest in land. For example, à privilege, or ‘profit a prendre’, allows the owner of that interest to enter a person’s land in order to take produce from it, such as crops or firewood, without actually being the owner of any land themselves.

Aim Higher

There are exceptions to this rule, as easement can only benefit an individual as the owner of the benefited land. This is discussed in further detail in Chapter 9.

As a property right, an interest in land can be sold by the owner of the interest or transferred to a third party in the same way as an estate in land can. The owner of an interest in land can also protect their interest as against a third party purchaser of the estate in which the interest is held.

Legal and equitable interests in land

Interests in land can be legal or equitable.

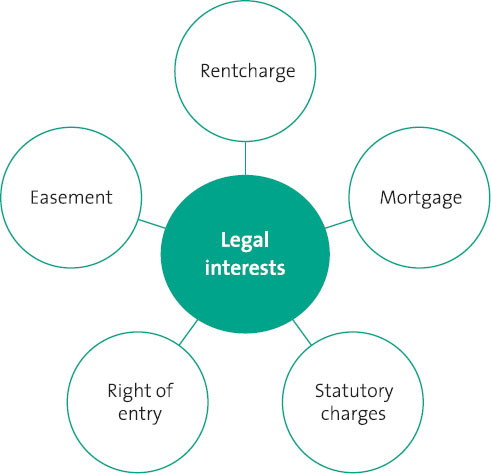

Legal interests

According to s 1(2) of the Law of Property Act 1925, there are five legal interests which can exist over land. These are:

(a) | an easement, right or privilege; |

(b) | a rentcharge; |

a charge by way of legal mortgage; | |

(d) | miscellaneous statutory charges; |

(e) | rights of entry. |

Section 1(2)(a) Easements and privileges

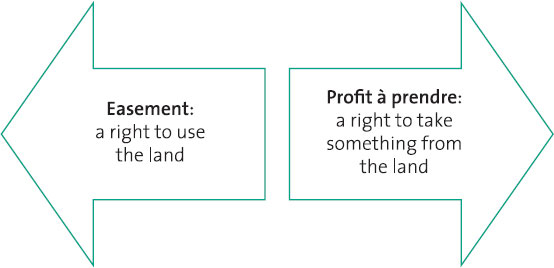

An easement is the right of one landowner to use or to restrict the use of the land of another. The most common right of user would be a right of way.

A privilege is an old-fashioned legal term for a ‘profit à prendre’. Profits differ from easements in that they allow the owner of the profit to take produce from the land, such as fish, wood or hay, as opposed to simply making use of the land in some way. Profits à prendre are a very ancient class of right and are rare.

Section 1(2)(b) Rentcharges

A rentcharge is the right to receive a periodic payment from the owner of freehold land. The concept of the rentcharge is now largely outdated and the creation of new rentcharges, with the exception of the estate rentcharge (a charge made to pay for the provision of services and maintenance on a housing estate), has been prohibited under the Rentcharges Act 1977. Under the Act, all other existing rentcharges are also being phased out by 2037.

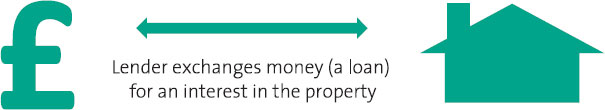

Section 1(2)(c) Charge by way of legal mortgage

A ‘charge by way of legal mortgage’ is the correct legal terminology for a mortgage entered into under the Law of Property Act 1925, A mortgage is where a person borrows money, usually to buy a house, and the lender takes, as security for the loan, a charge or mortgage over the property.

This gives the lender a legal interest in the property, which entitles them to take possession of the house and sell it to repay the outstanding debt if the borrower does not repay the loan.

Section 1(2)(d) Miscellaneous statutory charges

There is no form of legal interest under the current law that fits into this category.

Section 1(2)(e) Rights of entry

A right of entry is the right of a landlord to enter their tenant’s property and reclaim possession of it, where the tenant has breached one or more of the terms of the lease.

Creation of legal interests

In order for any interest in land to be legal, it must be:

a) | one of the five kinds of interest listed under s 1(2) of the Law of Property Act 1925; and |

b) | made by deed (s 52(1) LPA 1925). |

c) | In addition, where the land is registered, the interest must be registered against the property at the Land Registry in order to become a valid legal interest (s 27(2)(d) Land Registration Act 2002). |

d) | Easements and profits must also be created for a period equivalent to a legal estate in land: that is, either for an unlimited period (in fee simple absolute), or for a fixed and certain period of time (term of years absolute). |

Failure to comply with any of these requirements will result in the interest taking place in equity only. It is in this way that it is possible to have an equitable easement or an equitable mortgage.

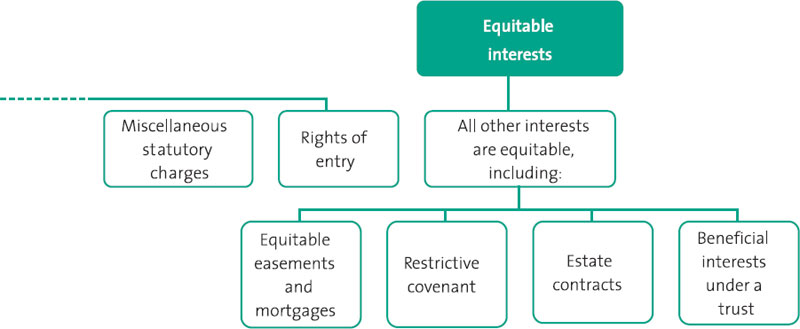

Equitable interests

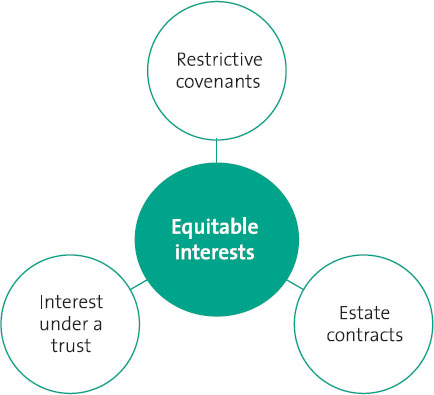

Under s 1(3) of the Law of Property Act 1925, any interest in land that does not fall within the categories listed at s 1(2) of the Act will exist only in equity.

There are many different types of equitable interest in land, but the most common of these are estate contracts, restrictive covenants and beneficial interests under a trust.

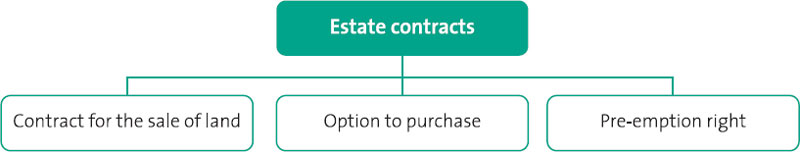

Estate contracts

An estate contract is a contract for the sale and purchase of land. A simple contract for the purchase of residential property is the most common form of estate contract, but there are also other forms of estate contract, including options to purchase (the right to purchase the land within a fixed time period) and pre-emption rights (rights of first refusal on land).

Restrictive covenants

A restrictive covenant is a promise by the landowner not to do a particular act on or in relation to their land. This might include a covenant not to build on the land, or not to use premises for business purposes, for example. You will be considering the concept of restrictive covenants in detail in Chapter 10.

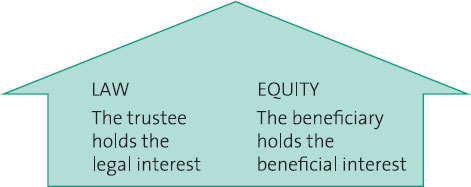

Beneficial interests under a trust

A trust of land will exist wherever one person holds the legal title to property on behalf of, or for the benefit of another. You have seen how this can happen in Chapter 1 where land is jointly owned by two or more persons.

Points to remember about estates and interests in land

Aim Higher

Being able to identify the various different types of legal and equitable estates and interests in land is vital to being able to answer a question on the topic of interests in land in an exam scenario, and a great first step to take towards mastering this topic.

However, examiners will also expect you to be able to explain how to protect these various interests and apply this to the facts of a problem question scenario. The next section of the chapter shows you how to do this.

Protecting interests in registered and unregistered land

Registered land

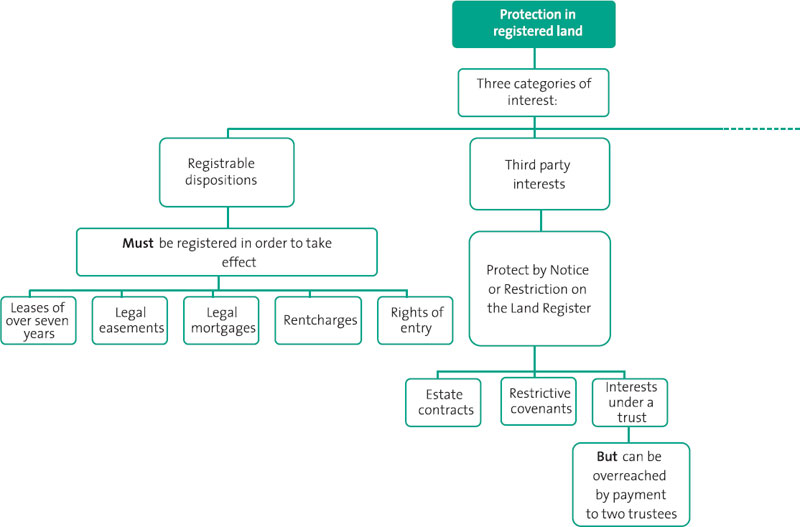

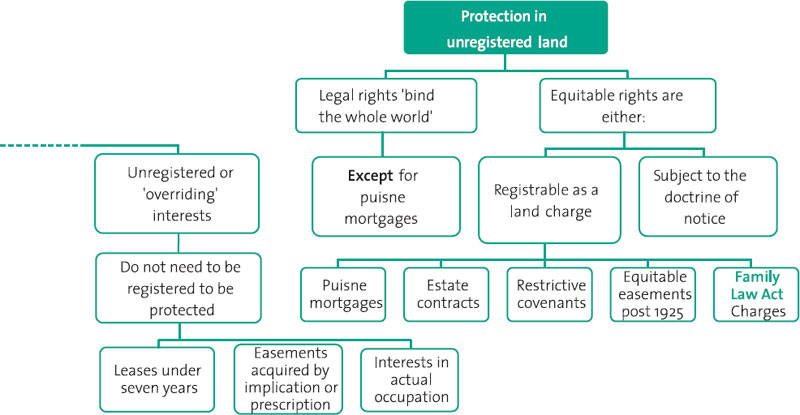

The current system of land registration under the Land Registration Act 2002 separates rights and interests in land into three categories:

registrable interests or dispositions;

registrable interests or dispositions;

third party rights and interests;

third party rights and interests;

unregistered or ‘overriding’ interests.

unregistered or ‘overriding’ interests.

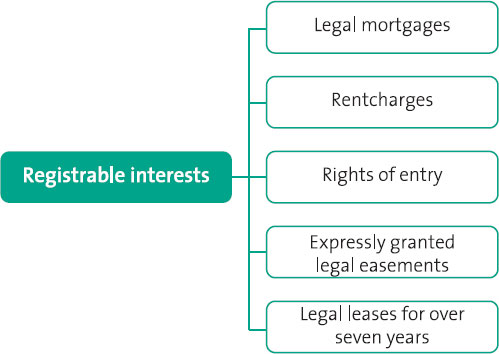

Registrable interests

Registrable interests are listed under s 27(2) of the Land Registration Act 2002. Included in this category are the four current legal interests in land listed under s 1(2) of the Law of Property Act 1925.

Legal leases for over seven years’ duration also come within this category.

Rights in this category must be registered in order to take legal effect. If they are registered, they will bind any purchaser of a legal estate in the land affected by the interest.

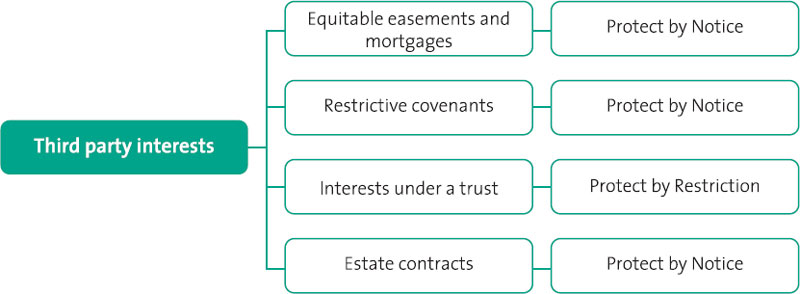

Any other kind of interest in land is classed under the Land Registration Act 2002 as a third party interest in land. Such interests include all equitable interests over land, covering equitable easements and mortgages, restrictive covenants, interests behind a trust and estate contracts.

Registration of third party interests is not compulsory, but the owner of the interest can protect it by registering the interest against the property over which they hold the right, either by ‘Notice’ or ‘Restriction’. The burden of a restrictive covenant or estate contract would be protected by Notice, an interest under a trust by Restriction.

Failure to register an interest as a Notice or a Restriction will mean that a third party will not be bound by interest. This is regardless of whether the third party knew about the interest or not.

Case precedent – De Lusignan v Johnson [1973] 230 EG 499

Facts: A lender knew that a contract had been entered into for the sale of property over which the lender was taking a mortgage, but the lender was able to take free of the contract because it had not been registered at the Land Registry.

Principle: Failure to register a third party interest will result in the owner of the interest having no way of protecting that interest.

Application: Use this case to show the strict application of this principle. Nonregistration will result in no protection, regardless of knowledge.

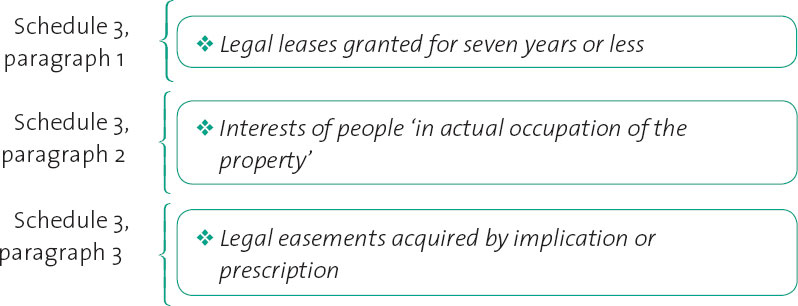

Unregistered or ‘overriding’ interests

In spite of the above, there are certain third party interests that will bind a purchaser of registered land even where those interests have not been protected by the registration of a Notice or Restriction at the Land Registry. These interests are listed at Schedule 3 of the Land Registration Act 2002 and include:

Legal leases granted for seven years or less