The Ramsar Convention on Wetlands of International Importance

6 The Ramsar Convention

on Wetlands of

International Importance

1 Introduction

In her review of international legal responses for the conservation of coral reefs, Mary Davidson unfortunately overlooked the 1971 Convention on Wetlands of International Importance Especially as Waterfowl Habitat,1 otherwise known as the Ramsar Convention after the Iranian town where it was adopted.2 This is easily forgiven. Changing widely held perceptions that wetlands include a greater variety of habitats than just inland waters has caused one major coral reef nation implementation difficulties,3 whilst a senior advisor to Ramsar has also noted that ‘the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands [includes] coral reefs but that, unfortunately, this [is] not well known, particularly among governments’.4

In 1984, Sue Wells identified Ramsar’s potential for protecting coral reefs.5 At the time, she noted that there was a need for the international community to support states already taking action to protect reefs, and that international recognition of sites would assist these national efforts. Ramsar offered a mechanism for such recognition, although its potential was largely unrealised because of a lack of participation and listing of coral reef sites.6

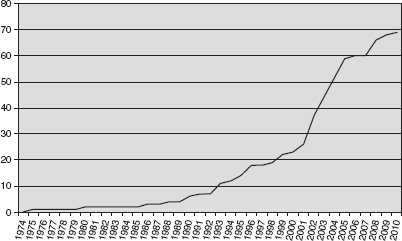

This chapter updates that study and reveals the key role the convention has today in conserving coral reefs. As will be explained, the dominant approach under Ramsar is to promote the use of MPAs; perhaps the most important strategy for these ecosystems after tackling climate change and ocean acidification. What is more, the value of Ramsar for promoting the conservation of coral reefs through such enclaves is growing steadily. That increasing importance becomes apparent when comparisons are made between the situation today and at the time of Wells’ study in terms of the geographical coverage of Ramsar and progress in designating coral reef sites. Finally, and as revealed in this book, with a number of MEAs being influential in conserving coral reefs, an assessment of Ramsar’s merits for dealing with these ecosystems will be undertaken.

2 The Ramsar Convention

For the purposes of this chapter, it is useful to provide a general introduction to the treaty. However, as this study aims to focus attention upon the promotion under Ramsar of the conservation of one wetland type (coral reefs), it is not intended to serve as an analysis of the convention as a whole. Many able studies have already been undertaken in that regard.7 This section will therefore provide a general primer on the convention, whilst examining a few provisions in greater detail on the basis of their particular relevance to later arguments.

2.1 Background to the convention’s conclusion

In 1971, the year before the UN Conference on the Human Environment was held in Stockholm, Ramsar was concluded as the first global agreement to deal with a particular habitat. Wetlands had long been the subject of land reclamation and drainage, despite their significance for regulating water levels and as habitat for fish, reptiles and waterfowl. The loss of wetland habitat was therefore taking place on a large scale, causing particular concern to ornithological NGOs. These groups led the negotiations for what eventually became the treaty. This fact continues to be reflected in the full title and certain provisions of the convention, making attempts to distance the regime from such an apparent focus upon waterfowl necessary.8 Ramsar has thus had to contend with ensuring that the full spectrum of wetland habitats is being protected under its auspices. It has also had to try to attract the membership of states who may have felt that the convention was only relevant to waterfowl conservation and therefore did not fit with their own priorities. Just as big an issue has been introducing practices to better reflect the gradual development of modern environmental law since the Stockholm Conference.

2.2 Defining and subdividing wetlands

Ramsar recognises that wetlands are important regulators of water regimes and, more particularly, act as habitats supporting characteristic flora and fauna.9 As such, Ramsar was the first MEA to address the conservation of a particular habitat – i.e. those collectively regarded as wetlands. The definition of wetlands was established in Article 1(1) as:

areas of marsh, fen, peatland or water, whether natural or artificial, permanent or temporary, with water that is static or flowing, fresh, brackish or salt, including areas of marine water the depth of which at low tide does not exceed six metres.

The key to understanding Ramsar is to realise that wetlands falling within this definition may also be inscribed on the Ramsar List of Wetlands of International Importance (the ‘List’); a smaller subcategory of special wetlands to which additional obligations apply. This important subdivision of wetlands is effectuated through the provisions of Article 2, which states in the first subsection that each contracting party shall designate ‘suitable wetlands within its territory for inclusion in a List of Wetlands of International Importance, hereinafter referred to as “the List”’. A ‘suitable’ wetland is one that is significant in ecological, botanical, zoological, hydrological or limnological terms.10

The inclusion of a site in the List is supposed to be the end result of the following systematic approach involving identification and designation. First, Ramsar has called upon contracting parties to draw up an inventory of all wetlands within their territories that are considered to be of international importance in accordance with the latest criteria and guidance.11 This identification process puts states in a better position to undertake the second stage of choosing which sites they will place in the List. Designation is accordingly a unilateral act by the contracting party.12 The only imposition placed upon contracting parties with regard to listing sites is that they must designate at least one wetland when they sign, or ratify/accede to, the convention.13

The Ramsar parties have sought to ensure that the designation and listing of a wetland as internationally important be accompanied by a number of documents deposited with the Ramsar Secretariat.14 These documents include site descriptions, maps and a completed Ramsar Information Sheet.15

2.3 Obligations relating to all wetlands

Ramsar seeks to conserve wetlands through obligations applicable to all such sites, with additional obligations applying to the more ‘exclusive’ group of listed wet-lands. Thus, the following obligations apply equally to wetlands whether listed or not:

1 to promote conservation by establishing nature reserves with adequate wardening,16

2 to encourage research regarding wetlands and related flora and fauna,17

3 to promote the training of personnel competent in the fields of wetland research and management,18 and

4 to co-operate with other contracting parties with respect to transboundary wetlands.19

In addition to the above, Article 3(1) provides that: ‘Contracting Parties shall formulate and implement their planning so as to promote the conservation of the wetlands included in the List, and as far as possible the wise use of wetlands in their territory.’ The effect of this important provision has been the subject of much academic analysis in an attempt to clarify whether the standards of ‘conservation’ for listed sites, and ‘wise use’ for non-listed sites, amount to the same level of protection.20 Such debates are relevant given that they impact upon this study’s view as to whether Article 3(1) establishes an obligation applicable to all wetlands, or alternatively a distinct obligation for those wetlands that have been listed.

In recent years it seems that attempts have been made to equate conservation with wise use. In 1987, at COP3 in Regina, wise use was defined as the sustainable utilisation of wetlands for the benefit of humans but compatible with maintaining the natural properties of the wetland ecosystem.21 The definition of wise use has since been updated to reflect the developments under the CBD, the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment and the ecosystem approach so that it now provides that: ‘Wise use of wetlands is the maintenance of their ecological character, achieved through the implementation of ecosystem approaches, within the context of sustainable development.’22

If conservation of internationally important wetlands were to be accorded a different meaning, therefore, a higher standard of maintenance (perhaps more preservationist) with less human interference would be expected.23 Yet this may not accord with notable interpretations of conservation, or the general approach of Ramsar and the contracting parties.

The term ‘conservation’ is not subject to clarification by the convention, however, as Michael Bowman notes, the modern notions of the term are almost identical to the Ramsar interpretation of wise use. In particular, the World Conservation Strategy defined conservation as yielding the greatest sustainable benefit to present and future generations.24

In addition, the contracting parties to Ramsar seem to be rejecting a preservationist interpretation of conservation, preferring instead the extension of wise use standards to listed wetlands. This tendency finds support in Ramsar’s Strategic Framework and Guidelines for the Future Development of the List, which emphasises the continuing need for all wetlands under the convention to remain a valuable resource.25 The same document goes on to note that the listing of a wetland is a first step, ‘the endpoint of which is achieving the long-term wise (sustainable) use of [that site]’.26 Resolution XI.1, which contains the updated definition of wise use, states that the new provision applies, as far as possible, to all wetlands.27 The wise use standard is therefore apparently being applied to listed sites as well as wetlands in general. Whilst the obligation in Article 3(1) is absolute with respect to listed sites, but only to be pursued ‘so far as possible’ for all others, it seems appropriate in the light of practice to regard the article as otherwise establishing a common expectation for all wetlands, regardless of listing.28

One further important requirement relating to the wise use of all wetlands is the formulation of National Wetland Policies, and guidelines have been produced to enable the contracting parties to meet the challenge of putting this into practice.29 Accordingly, the convention’s Guidelines for the Implementation of the Wise Use Concept observe: ‘It is desirable, in the long term, that all Contracting Parties should have comprehensive national wetland policies, formulated in whatever manner is appropriate to their national institutions.’30 This is because the achievement of wise use requires raising awareness, co-ordination and planning on a national scale. The guidelines draw particular attention to impact assessment of projects upon wetlands, continuous monitoring, designating sites as internationally important, establishing nature reserves generally and the involvement of stakeholders and local people in formulating policies.31 The latter drive is commendable as experience in managing coral reef ecosystems has shown that such involvement of local communities can encourage greater cooperation and thus compliance with national initiatives.32

2.4 Obligations relating only to listed wetlands

In relation to listed wetlands, parties must comply with two significant obligations. These provisions place restrictions upon parties’ freedom of dealing with wetlands and require a degree of investment in environmental monitoring, over and above the costs and constraints imposed by the generally applicable obligations noted previously.

Under Article 3(2), contracting parties must put in place mechanisms that will facilitate detection of changes in the ecological character of listed wetlands, whether likely or actual, caused by technological developments, pollution or other human interference. Such information is to be passed to the Ramsar Bureau who, with the contracting party’s consent, may add the wetland to a record of such sites undergoing change.33 Efforts can then be made to help the contracting party address the situation.

In addition, the removal or reduction in the size of a listed wetland by a contracting party for reasons of urgent national interest under Article 2(5) triggers an obligation under Article 4(2) to create additional nature reserves for waterfowl and to protect, either in the same area or elsewhere, an adequate portion of the original habitat, although only so ‘far as possible’.

2.5 Obligations between parties

Whilst parties are asked to exchange data, research and other publications on wetlands and their flora and fauna under Article 4(3), the principal obligation as between parties is contained in Article 5. Article 5 is divided into two themes. First, parties should consult each other generally with respect to implementing their obligations, especially when dealing with transboundary wetlands and shared water systems. Secondly, the parties should endeavour to coordinate and support present and future policies and regulations.

Such obligations have been pursued through a number of initiatives including twinning arrangements between listed sites and the development of regional committees. This reflects the recognition that sharing common experiences within regions and between the same wetland types engenders cooperation and knowledge exchange.

2.6 Institutional structure

It is generally recognised that for an MEA to be in a position to tackle any given environmental concern, it is desirable that the regime’s efforts be supported by a number of institutional bodies. Over time, Ramsar has established various bodies, even if the treaty did not originally provide for them. This modernisation in order to reflect best practices for administering MEAs has ensured Ramsar remains active and influential despite its origins at the beginning of the modern international environmental law movement.34

From the outset, the treaty provided for the convening of COPs when deemed necessary.35 Such COPs were competent to address a variety of issues, including implementation, changes to the List, changes in ecological character of listed wet-lands, the commissioning of reports and the adoption of recommendations on conservation and wise use. Such a system was not considered adequate and in 1987 amendments were introduced, with Article 6(1) being reformulated to establish regular (triennial) meetings of the COP. In addition to the competences previously described, a catch-all clause was inserted providing for the adoption of resolutions or recommendations to promote the functioning of Ramsar.

Also from the outset, the general administration of the regime has been supported by the Ramsar Bureau.36 The Ramsar Bureau is currently based at IUCN’s headquarters in Gland, and acts as the convention’s Secretariat with yearly work plans defining responsibilities. The Bureau’s administrative tasks currently include fostering links with other MEAs, maintaining the Ramsar List and preparing for upcoming COPs.

Subsequent to the entry into force of Ramsar, it was recognised that the institutional provisions of the convention needed supplementing, and thus two new bodies were established. The first was a Standing Committee whose brief was to carry out such work as was called for between COPs. The committee comprises representatives from the seven Ramsar regions, as well as from the previous and upcoming host state of a COP. The committee is of particular importance given its role in steering the convention’s future activities and in monitoring the activities of the Bureau.

Institutional support was further improved following the recognition by the Standing Committee that there was a need for better technical and scientific assistance. Consequently in 1993, the Scientific and Technical Review Panel (STRP) was established, and mandated to meet annually. The STRP comprises seven nominated experts for the Ramsar regions, six further members appointed in accordance with a desire to have balanced representation of regions and genders, and an additional expert with experience in communications, education and public awareness.37 Finally, the five International Organisation Partners38 are also permitted one representative on the panel.39 The panel members are required to act in an individual capacity, since contracting parties are expected to advance their views through the national focal points they can appoint specifically to liaise with the STRP.

2.7 Summary

In comparison to a number of more recent conventions, Ramsar contains few provisions – the original text runs to only 12 articles. Much of the detail has either been inserted through amendment or, as is more common, through the adoption of highly detailed guidance for the parties.40 Further, the convention has been able to evolve over time, particularly in institutional terms.

Central to the convention are those provisions dealing with the selection and designation of sites for the Ramsar List. This system of designating and protecting defined areas has consequences regarding the extra obligations that are pertinent to a particular wetland. It also means that MPAs are the dominant conservation strategy under Ramsar, although as will be seen, some contracting parties are also actively engaged in implementing further policies outside of these enclaves. Nevertheless, this subdivision of properties is not without criticism.41 Yet it remains a key element in the way Ramsar seeks to protect wetlands.

Having completed this brief introduction to the operation of Ramsar, and before moving on to judge the progress made by Ramsar in conserving coral reef ecosystems through MPAs since Wells’ study in 1984, two further issues merit consideration. The first is to review the dominance of MPAs as a conservation strategy. The second, and perhaps most crucial, how coral reefs fall within the jurisdiction of Ramsar as a type of wetland.

3 Marine protected areas under Ramsar

Whilst Ramsar encourages broader conservation measures for the wise use of wet-lands, protected areas (both marine and terrestrial) inevitably take a leading role in efforts promoted under the treaty.42 This is no bad thing in the context of reefs, as was mentioned in chapter 1. This centrality flows from two Ramsar provisions.

The first clear example of the promotion of MPA strategies is contained in Article 4(1), which requires that, ‘Each Contracting Party shall promote the conservation of wetlands and waterfowl by establishing nature reserves on wetlands, whether they are included in the List or not, and provide adequately for their wardening.’ Progress under this obligation is easier to judge for listed rather than non-listed wetlands due to the information provided to the Bureau in relation to the former and made available through the various databases. That said, Simon Lyster noted a number of examples of nature reserves being created on non-listed sites in some national reports submitted to the Ramsar Bureau, such as a total of 54,000 ha spread between 11 locations in Hungary and four similar sites in Iceland totalling 20,149 ha.43

Article 4(1) therefore highlights protected areas as an important strategy for meeting the conservation and wise use standards required for listed and non-listed wetlands. In particular, contracting parties have been reminded that of central importance to meeting this obligation will be the compilation of national wetland inventories, incorporating such areas within the management of the environment as a whole, employing different use zones within reserves where appropriate, and reviewing the legal mechanisms in place in any given state for establishing and managing such reserves effectively.44 It is also a stated aim of Recommendation 4.4 that contracting parties should focus upon creating a network of nature reserves for listed and non-listed wetlands within their territory. Again, all of this accords with advice on best practices for conserving coral reefs.

It can also be said that the List of Internationally Important Wetlands itself provides a further mechanism to promote protected areas. In order to make this argument, the commonly used definition of an MPA must be recalled, i.e. a geographically defined area of the sea and/or shoreline, which is designated or regulated and managed to achieve specific conservation objectives.45 Parties are required to define the boundaries of any listed wetland, within which Ramsar’s generally applicable obligations, and those more stringent restrictions relating to listed wet-lands, must be satisfied. Contracting parties will then need to translate this into practice and effect through implementation at the national level, thereby resulting in the listing mechanism under Article 2 having a direct influence upon a defined area of wetland, and protected area policies at state level.

Given the need to meet Ramsar’s obligations within the designated boundaries of listed sites, one approach that states can choose to adopt is to ensure that sites to be nominated for the Ramsar List are already subject to national regulation and management regimes. Thus Patricia Birnie and others note that a number of sites at the time of listing are already within nature reserves although they also suggest that others become so after listing.46

The convention has confirmed through guidelines that the area nominated for the Ramsar List need not enjoy protected area status prior to listing, nor is it demanded that such status be subsequently acquired.47 This has led to different approaches. As Lyster claims, the United Kingdom, Chile and the Netherlands are among those states that favour only the listing of sites that are already specially protected within an enclave, relying upon the international designation to provide an added commitment to their conservation and extra recognition of their significance.48 Alternatively, it has been argued, listing unprotected sites should be encouraged since it will generate national action to provide protection at the state level.49 Indonesia, for example, recently indicated it was considering the designation as Ramsar sites of areas currently outside of existing protected areas.50

Article 2 may therefore be of limited value to calls for increasing the number of MPAs for coral reef ecosystems. To an extent, past experience bears this out since the majority of such listed sites containing coral reefs already existed within enclaves before designation, with only a few becoming protected areas afterward. However, some states do seem to take the opportunity to enlarge nature reserves when listing under Ramsar.51

The Ramsar Convention therefore promotes MPAs for the conservation and wise use of marine wetlands through the provisions of Articles 2 and 4(1). The role the convention can play may be limited with respect to encouraging the creation of new MPAs, however its significance lies more in promoting better management and thus tackling the problems of paper parks. This comes about through the exposure of listed sites to the involvement and scrutiny of the international community, whether through national reporting or the Article 3(2) mechanism previously described. In addition, the obligations imposed under Ramsar may increase the level of protection that would otherwise have been provided under national provisions. Further, international recognition can help countries to promote and market wetlands to visitors, and help government departments charged with environmental affairs to secure the integrity of a site within national policy development. In all of these ways, the management of MPAs for marine wetlands can potentially be strengthened under Ramsar.

4 Legal competence under Ramsar

The convention’s definition of a wetland was briefly discussed in the previous section. Referring back to Article 1(1),52 a number of additional matters should be noted. First, individual wetlands are defined by reference to geomorphological areas sharing a common natural element – water. This was noted to an extent by Geoffrey Matthews: ‘All wetlands have one feature in common. They are based on a substrate that is at least occasionally covered or saturated with water.’53

This is further reflected in the system of wetland classification adopted for the Convention, which contains reference to such geomorphological areas as estuaries, karst systems, rocky shores, rivers and deltas.54 As noted earlier, the protection of these areas is important as they can act as habitats supporting characteristic flora and fauna.55

Secondly, it is clear that the remit of the convention is extremely wide. Over time this definition has accordingly allowed Ramsar to address the broad range of wetlands listed in the classification system. Indeed, it is worth recalling the lighthearted comment of IUCN’s former Director General when in 1990 he said ‘. . . only two Conventions are really needed to cover the conservation of all habitats in the world – the Ramsar Convention dealing with any land that can generally be termed “wet”, and a Drylands Convention dealing with anything else.’56

However, it is not entirely clear that the definition of ‘wetlands’ under the Ramsar Convention is wide enough to offer sufficient coverage for all coral reefs. To understand this concern, a brief recap on marine biology and the formation of coral reefs is needed.

As has already been described, reef building by warm-water corals through the deposit of calcium carbonate is limited by factors such as temperature, light levels, depth, sedimentation, salinity and exposure to the air.57 The availability of light is of paramount importance since individual corals are host to zooxanthellae, which, through photosynthesis, provide them with their main source of energy for the process of calcification.58 Insufficient light has the effect of reducing energy supply and accordingly inhibits the ability of corals to secrete calcium carbonate and thus build reefs. Given that light decreases with depth, reef formation is correspondingly limited. Reef building undertaken by corals therefore flourishes in water depths of less than 25m,59 and ceases altogether between 50–100m depending upon conditions.60 In order to complete the picture, upward reef formation is ultimately limited by exposure to air and therefore relates to the level of low tides.

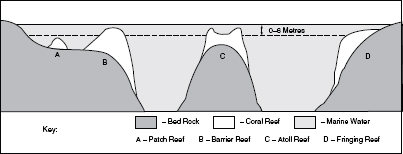

figure 5 recalls the main types of coral reef formation consequent to this process, these being fringing reefs, barrier reefs, atoll reefs, and patch reefs formed within the lagoons that result from atoll and barrier reefs. Atolls arise in relation to volcanic activity that sees an island initially created (around which a collar of fringing reef forms), but which then subsides back into the ocean. Where upward coral growth is faster than the speed of descent as the island subsides, a ring-shaped atoll will be formed.61

As the dotted line in figure 5 indicates, in relation to almost all atoll (C), barrier (B) and fringing reefs (D), the physical substrate of a reef will develop both above and below the 6m depth limit stipulated for wetlands falling within the convention’s jurisdiction. It is also possible for no part of a coral reef to form within the 0–6m limit. The isolated dive site of ‘Magic Mountain’ off the coast of Sumba Island in Indonesia is a submerged seamount of coral reefs (not indicated in the figure) that, at its shallowest, comes within 8–10m of the surface, but whose reef slopes drop away to depths in excess of 60m.62 Further, patch reefs (A), which form on lagoon floors, may or may not develop to a height within the 0–6m limit.63

Given the above, a potentially significant problem with the way in which Article 1(1) has been drafted can be identified. The limits of the geomorphological area used to define wetlands under the convention – unambiguous limits that in the absence of specific revision or amendment it is problematic to suggest should simply be ignored64– excludes all but the upper portion of the reef structure for the vast majority of coral reefs and maybe even excludes entire reefs in more exceptional circumstances.

As coral reefs may form in less than a six metre depth of water they can correctly be regarded as a type of wetland. However, Article 1(1) does not seek to delimit jurisdiction by reference to types of habitat that can potentially meet the definition, with the result that all actual examples of such habitats automatically fall within Ramsar’s authority. Instead the definition of wetland looks to delimit the application of the convention on a site by site basis, so that each particular site must meet the definition. Therefore, from this perspective, what is the position for structural elements below the depth limit or the ‘Magic Mountain’ scenario where no part of the reef structure lies within the upper 6m of the marine water? If the zones below this limit are not within the jurisdiction of the convention, then vast areas may justifiably be regarded as exempt from the obligations under Ramsar. This presents governments with an arguable case for failing to pursue a comprehensive policy for protecting coral reefs under the convention.

In practice, and as will be seen in the following sections, the inclusion of entire coral reef ecosystems has not proved contentious and, more importantly, is often demanded. References to coral reefs in Ramsar documents do not contain a qualification as being applicable only to those parts of coral reefs lying within a depth of 6m. This situation, where coral reefs are being dealt with without noticeable objection, suggests that there must be a favourable way of interpreting or applying the convention so as to extend the operation of the convention into waters deeper than 6m. The following sections explore a number of ways of doing this.

4.1 Increasing the depth limit by reference to Article 2(1)

According to Sir Gerald Fitzmaurice’s formulation of the major principles of interpretation, and as supported in Article 31(1) of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties:65 ‘Treaties are to be interpreted as a whole, and particular parts, chapters or sections also as a whole.’66

This may seem like common sense, meaning that Article 1(1) should not be interpreted in isolation, but also in the light of the rest of the convention’s provisions as part of the context in which the definition lies.

Such wider reflection initially highlights Article 2(1); an article that has been described as effectively extending the wetlands definition.67 The terms of this provision state that the boundaries of each listed wetland ‘may incorporate riparian and coastal zones adjacent to the wetlands, and islands or bodies of marine water deeper than six metres at low tide lying within the wetlands . . .’. Does this article therefore extend the limits of the wetland definition into waters deeper than six metres? Unfortunately, only to a limited extent, for the following reasons.

First, the provision applies only to the smaller category of internationally important wetlands included on the Ramsar List, negating a possible extension to all coral reefs generally. Second, the article simply refers to acceptable boundaries for reserves, rather than changing the actual definition of wetlands.68 As mentioned earlier, in designating an internationally important coral reef, a map indicating the boundaries of the site must be submitted.69 Those boundaries need not be determined in accordance with the limitations provided for in the wetlands definition in Article 1(1).70

The consequences of this are that, in practice, the whole area within the boundary will be subject to both the generally applicable and particular obligations for listed wetlands, as described earlier. In this sense, it could be said that the definition of listed wetlands has been effectively, albeit not formally, enlarged. This interpretation also maintains a unified definition of wetland rather than postulating a wider definition for the smaller subcategory of listed wetlands, which would pose logical difficulties.

If this provision is applied to the various reef formations as represented in figure 5, the final limitation to Article 2(1) can be identified. The Guidance for Identifying and Designating Peatlands, Wet Grasslands, Mangroves and Coral Reefs as Wetlands of International Importance claims that: