Trusts and Proprietary Estoppel

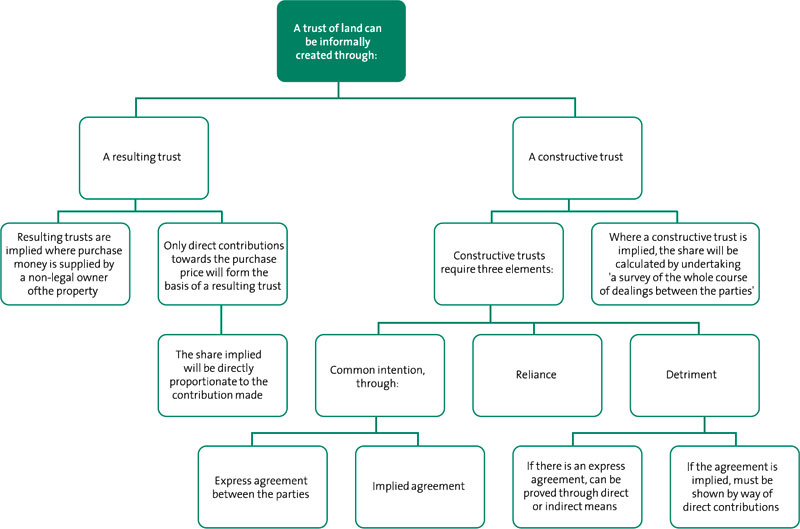

The creation of express trusts falls outside the scope of this text and is considered more fully in the Trusts text in the Optimize series. Informally created trusts of land, however, are often encountered in land law, particularly in the context of the family home. There are two types of informally created trusts of land:

resulting trusts; and

resulting trusts; and

constructive trusts.

constructive trusts.

Resulting and constructive trusts are different from other interests in land in that they can be created without the need for writing, or indeed any formality (s 53(2) LPA 1925).

Understanding: resulting trusts

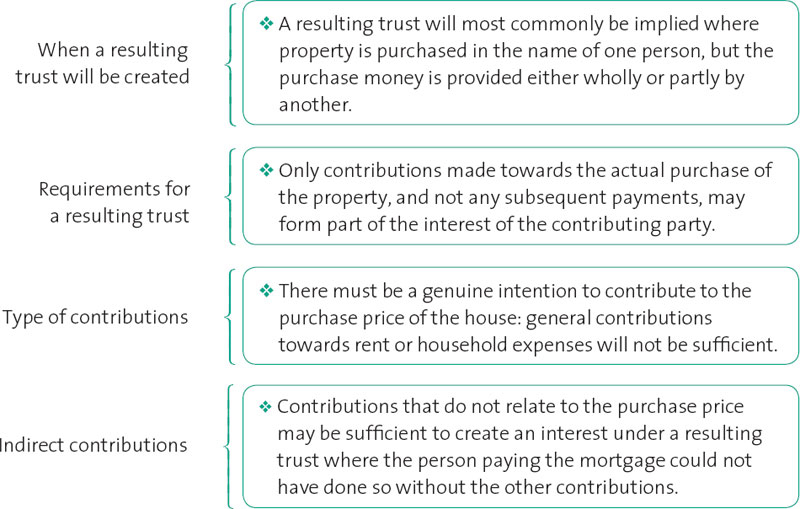

In the context of land law, resulting trusts are most commonly encountered where property is purchased in the name of one person, but the purchase money is provided either wholly or partly by another.

In these circumstances, the legal owner of the property will be viewed as holding the property on trust together for themselves and the person who contributed to the purchase price, in proportion to the shares they put into the property.

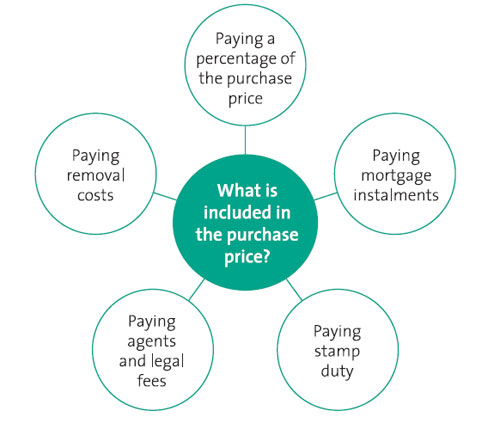

Only contributions towards the actual purchase of the property, and not any subsequent payments, may form the interest of the contributing party.

However, payments towards mortgage instalments will be construed as payments towards part of the purchase price of the property, albeit that they are paid over a period of time and not just at the time of purchase. However, it should be noted that contributions to the purchase price must be both specific and contemporary to the purchase.

In addition, the courts must be able to attribute to such payments a genuine intention to contribute to the purchase price of the house: general contributions towards rent or household expenses will not be sufficient (Savage v Dunningham [1974] Ch 181).

Case precedent – Pettitt v Pettitt [1970] AC 777

Facts: A wife inherited a house which she and her husband lived in for a number of years. The wife then sold the house, using the proceeds to buy a plot of land, again in her sole name, on which to build a bungalow for her and her husband to live in. On the couple’s subsequent divorce, the husband claimed a share of the bungalow on the grounds that he had spent money and effort in redecorating and improving it. Held: The improvements bore no relation to the purchase of the house and could therefore not amount to a beneficial interest under a resulting trust.

Principle: In order to make an award of a resulting trust, the contributions must be directly attributable to the purchase of the property. More general contributions to the running or subsequent improvement of the house will not be sufficient.

Application: Use this case as an example of a case in which a resulting trust will not be created.

Aim Higher

So how can you tell what will be included and what will not?

It is the timing of the creation of the interest that is crucial in the resulting trust scenario: resulting trusts are based on the presumed intention of the parties at the time the property is acquired; thus, payment for works or improvements to the property will not be taken into account. On this basis, the beneficial share of property acquired under a resulting trust will be established at the time the property is purchased and will be unaffected by any later payments for improvements to the house or contributions to its upkeep.

Case precedent – Gissing v Gissing [1971] AC 886

Facts: A husband and wife lived together in a house registered in the husband’s sole name. When the husband later left the wife, she claimed an interest in the house on the basis that she had contributed money from her savings to pay for a new lawn and furniture for the house, as well as contributing from her earnings to the housekeeping and clothes for the family. Held: The wife’s claim was dismissed: her contributions were not sufficient to give her a beneficial interest in the house.

Application: Use this case as an example of a case in which a resulting trust will not be created.

Up for Debate

In the case of Burns v Burns [1984], the court held that a woman who had stayed at home to look after the children and subsequently paid for furniture, fixtures and fittings for the house was not entitled to a beneficial interest under a resulting trust, because she had not contributed towards the purchase of the property. However, May LJ’s judgment in the case is nevertheless interesting because of the way in which he approaches the issue of contributions. He suggests that the contributions made to the purchase of a property may be broadly divided into two categories: direct contributions, which include payments made specifically towards the purchase of the property; and indirect contributions, which include payments towards household expenses which the legal owner of the property would otherwise be unable to meet, in addition to making the mortgage payments.

This might appear to suggest that contributions that do not relate to the purchase price can be sufficient to create an interest under a resulting trust. However, such contributions will only be taken into account under circumstances where the person paying the mortgage could not have done so if their partner had not paid the other household bills.

Points to remember about resulting trusts

Understanding: constructive trusts

Constructive trusts are much wider in their application than resulting trusts, imposing a constructive trust wherever the conduct of the parties is such that equity requires it, albeit within certain prescribed guidelines.

According to Lord Bridge’s judgment in Lloyds Bank v Rosset [1991], there are three requirements for the finding of a constructive trust:

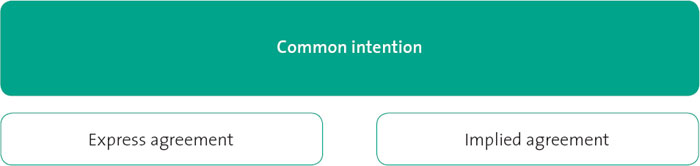

Common intention

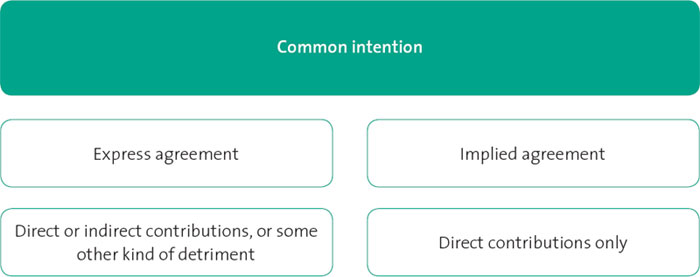

A common intention will be shown to exist wherever there is some form of agreement or understanding between the parties that the person making the claim will have a beneficial interest in the property. This can be shown either by express agreement, where there have been express discussions between the parties that the claimant is to have a beneficial interest in the property, or by implied agreement, where such an agreement is implied from the parties’ conduct.

Express agreement

Case precedent – Eves v Eves [1975] 1 WLR 1338

Facts: A man bought a house for him and his girlfriend to live in, which he registered in his sole name. He told the girlfriend that this was because she was under the age of 21 and therefore unable to go on the title deeds. However, he said that he would rectify this when she reached the age of majority. Held: As there had been an express agreement between the parties regarding beneficial ownership of the property, the girlfriend’s contributions to the property were sufficient to confer a beneficial interest on her.

Principle: A common intention between the parties will be shown where there has been an express agreement between them that the claimant is to have a beneficial share.

Application: Use this case to illustrate what will constitute an express agreement.

Common intention will not always be as easy to establish as in the case of Eves v Eves, because there will rarely have been an explicit agreement made between the parties as to how the property is to be shared and, if there was an agreement, it is likely to have been oral. In the absence of such proof, Viscount Dilhorne in Lloyds v Rosset warned that the courts must be careful not to impute the parties’ intention: making inferences as to what the parties might have done if they had considered it at the time. The common intention must in all cases be genuine.

Implied agreement

In the absence of an express agreement, the court may look to the conduct of the parties to see whether such an agreement can be implied from it.

Conduct amounting to an implied agreement is usually measured by reference to the financial contribution that has been made by the claimant to the purchase of the property. In this context, only direct contributions to the purchase of the house will be considered sufficient to imply an agreement between the parties.

Case precedent – Lloyds Bank plc v Rosset [1991] 1 AC 107

Facts: A husband and wife planned to buy a semi-derelict house together as a renovation project. The house was to be paid for with money from the husband’s family trust in Switzerland and the trustees insisted on the house being registered in his sole name. The wife made no financial contribution to the purchase, but she project-managed the renovation and carried out much of the decorating. When the couple subsequently split up, the wife claimed a beneficial interest in the property. Held: The wife’s contributions were insufficient to create an interest under a constructive trust.

Principle: Where common intention is inferred from the parties’ conduct, nothing less than direct contributions to the purchase price will be sufficient evidence of such an intention.

Application: Use this case to illustrate the meaning of indirect contributions.

Reliance

Reliance in the context of constructive trusts can be described as a situation in which the claimant has acted or changed their position in reliance on the parties’ common intention, whether express or implied. Reliance will usually be seen to be proved automatically where a detriment has been established.

Facts: The claimant relied upon her boyfriend’s representation to her that the only reason she didn’t appear on the title deeds to the property was because it would complicate her divorce proceedings against her husband. As a result, she acted severely to her detriment by making significant financial contributions to the running of the house. Held: There was a common intention between the parties that the woman was to have a beneficial interest in the property.

Principle: Reliance is the situation in which the claimant has acted or changed their position in reliance on the parties’ common intention.

Application: Compare the facts of this case against those in your own scenario to gauge whether there has been reliance by the claimant.

Detriment

In order to prove detriment, it must be shown that the claimant will suffer loss if the landowner denies them an interest in the property.

Where there is an express agreement between the parties, this detriment may be proved where the claimant has made contributions to the purchase of the property, whether direct or indirect, or it may take some other form.

Thus, in Eves v Eves, where there was an express agreement between the parties regarding beneficial ownership of the property, the court held that the girlfriend’s contributions to the renovation of the property and maintenance of the house and garden were sufficient by way of indirect contribution to entitle her to a quarter share in the house. See also Grant v Edwards [1986], which turned on similar facts.

Where the agreement between the parties is implied, rather than express, only direct contributions to the purchase of the property will be sufficient to establish an interest under a constructive trust.

In the case of Burns v Burns, mentioned above, the court held that the woman, who had bought furniture, fixtures and fittings for the house and did some painting and redecoration, did not have an interest by virtue of a constructive trust because she had made no contributions referable to the acquisition of an interest in the property. Echoing the finding in Rosset, Fox LJ said that, even in the case of indirect contributions, nothing short of substantial contributions enabling the legal owner to pay mortgage instalments will suffice. This seems to contradict the findings in Eves v Eves and Grant v Edwards. However, the wife in Burns v Burns had made no contribution of her own money to the property, her ‘contributions’ being out of housekeeping money given to her by her husband; in Eves v Eves the wife had made a substantial contribution of her own time and effort.

Where the detriment shown is not of a financial nature, it must be sufficiently serious to warrant the award of an interest in the property.

Case precedent – Ungurian v Lesnoff [1990] Ch 206

Facts: A Polish woman set up home with a man in London. Poland was at that time under Communist rule and, in order to achieve this, she had to give up her flat and a promising career, and sever all ties with her family in Poland. In addition she had to enter into a marriage of convenience with a third party in order to get out of the country. Held: The woman had a beneficial interest in the property under a constructive trust, based on the couple’s agreement that she would be entitled to live in the property with her children for the rest of her life.

Principle: Where there has been an express agreement between the parties, the detriment need not be directly referable to the purchase of the property.

Application: Use this case of an example of a situation in which a non-financial detriment will create an interest under a constructive trust.

Case precedent – Hammond v Mitchell [1991] 1 WLR 1127

Facts: A couple lived together for 11 years, during which time they had two children. The house in which they lived together was bought and paid for by the man, which he said was to save complications in his divorce proceedings. However, he told his partner not to worry because they would soon be married and half of everything would be hers anyway. The woman ran the household and helped out with the man’s business on a day-to-day basis, giving up a lucrative position as a croupier at a casino in order to do this. Held: The woman had acted to her detriment and was therefore entitled to a half share of the house under a constructive trust.

Principle: Where there is an express agreement, the detriment need not be directly referable to the purchase of the property.

Calculating the share

Once a beneficial interest under a constructive trust has been established, even where that interest has been established by virtue of direct contributions by the claimant, the calculation of their share in the property will not be limited to the value of those contributions alone. Instead, the court will look at the ‘whole course of dealing between the parties’ and make their finding based on what they believe to have been the parties’ intentions at the time of the purchase.

Case precedent – Midland Bank plc v Cooke (1995) 27 HLR 733

Facts: A husband and wife lived in a house registered in the man’s sole name and paid for out of a mixture of his own funds and some money given to the couple as a wedding gift. Held: At first instance that the wife should have a 6.47 per cent share, representing her half of the wedding gift. However, the Court of Appeal overturned this decision, giving the wife a 50 per cent share in the property. The wife had always been treated as an equal partner in the marriage, both in terms of paying household expenses from her wages and generally in keeping house and bringing up the children. As such, the implied intention was that they intended to share everything equally, including the matrimonial home.

Principle: The court will look at the ‘whole course of dealing between the parties’ when calculating share.

Application: Use this case to support your claim in respect of calculation of share.