United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea and the regional seas agreements

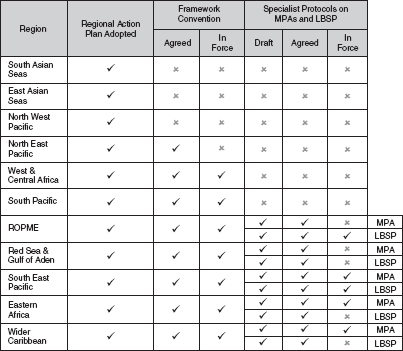

This chapter will begin by focusing upon the conservation of coral reef ecosystems to the extent that this is encouraged under the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea1 (LOSC). It is worth cautioning from the start that the LOSC has a limited role in promoting conservation of these ecosystems, especially regarding protected area strategies and tackling land-based sources of pollution. Instead, as was explained in the preceding chapter, the convention’s main impact for conservation lies in its regulation of the powers of coastal states in their maritime zones. This affects fisheries and environmental responsibilities, and the regulation of other marine activities. Nevertheless, the regional sea agreements applicable to maritime areas in which coral reefs naturally occur have a more prominent role in promoting conservation, and they are considered in the second half of the chapter. The reasons for considering both the regional agreements and the LOSC together stems from the latter’s advocacy under Article 197 of regional approaches for tackling environmental protection. The historical developments leading up to the conclusion of the LOSC have already been described.2 It should be recalled that the treaty was negotiated in part against the backdrop of a growing desire amongst coastal states to address in a comprehensive manner, issues of pollution and overfishing near to their coastal waters. As a motivation for reformulating the law of the sea, such environmental issues had at that time assumed added significance following the conclusion of the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment held in Stockholm in 1972.3 The restatement agreed, therefore, contained matters of interest to environmental lawyers. This is immediately apparent in the Preamble to the LOSC, which recognises the desirability of establishing: a legal order for the seas and oceans which will facilitate communication, and will promote the peaceful uses of the seas and oceans, the equitable and efficient utilisation of their resources, the conservation of their living resources, and the study, protection and preservation of the marine environment.4 The treaty adopted included provisions on the design and construction of ships (which it was hoped would have a knock-on effect on reducing pollution following collisions at sea), the management of fisheries outside of coastal states’ territorial waters and marine pollution more generally. Further, Part XII of the LOSC focused upon the marine environment and contains many of the core articles of interest to this study. Consequently, the LOSC and these environmental provisions have been afforded great significance by some academic writers, with Jonathan Charney describing the LOSC as: the most comprehensive and progressive international environmental law of any modern international agreement. Not only does the Convention successfully address marine environment issues, it serves as a prototype for environmental agreements in other fields.5 The role of the LOSC as a model for the evolution of international environmental law had also been espoused in the 1989 report on the law of the sea and the protection of the environment by the UN Secretary-General to the General Assembly.6 In particular, the Secretary-General highlighted the LOSC’s contribution to the concept of preventing transboundary pollution, and the completion of environmental impact assessments.7 In fairness, much of the claimed status rests upon the detailed pollution provisions. These included regulations on vessel-source pollution, moves to enhance enforcement of pollution laws through affording greater powers to coastal and port states, and some of the first attempts to tackle land-based sources of pollution. However, such claimed significance for the LOSC is questionable both from a general environmental perspective and the specialist focus of this book.8 For example, it has been argued that the LOSC fails to reflect the modern focus on sustainable development.9 Indeed, Richard Falk and Hilal Elver speculate that: if the negotiations had occurred in the 1990s, then it would seem likely that the language of ‘sustainable development’ would have been used to clarify the overall approach to environmental protection . . .10 More particularly, and as will be explained, the LOSC has a limited significance for the conservation of coral reef ecosystems. For example, the provisions on fisheries are only applicable within the EEZ of a coastal state and in the high seas. As was observed in the previous chapter, given the shallow-water location of reefs, they are not a high seas habitat, whilst the EEZ is suspected to be home to a smaller proportion. Indeed, the majority of reefs are likely to lie within internal or territorial waters. Further, the strongest provisions on pollution – such as those concerning vessel-source pollution – relate to events that are of limited significance as a threat to coral reefs.11 Meanwhile, those on land-based sources of pollution will be shown to be substantively weak. Finally, the LOSC offers few provisions that can be interpreted as a general call for conservation of reefs, or that explicitly encourage the key strategy of establishing marine protected areas (MPAs).12 These positions will be explained in the following sections, which cover the provisions of the LOSC on controlling fishing, land-based sources of pollution and MPAs. Whilst this section will consider the promotion of MPAs, it is worth highlighting the opening articles of Part XII that are of relevance to all of the sections in this chapter. Article 192 declares that ‘states have the obligation to protect and preserve the marine environment’. This provision is notable for a couple of reasons. First, the obligation is unqualified. It is not framed so as to be performed ‘as far as possible’ or in accordance with a state’s capabilities.13 It obliges states to protect and preserve the global marine environment throughout all of the maritime zones to the same (albeit unknown) degree. Second, the article is often regarded as a statement of customary international law,14 and as such is binding as a legal undertaking upon states that are parties to the LOSC, as well as upon non-contracting parties in the absence of persistent objection on their part. This obligation is followed by Article 193: States have the sovereign right to exploit their natural resources pursuant to their environmental policies and in accordance with their duty to protect and preserve the marine environment. Article 193 is significant in recognising the right of states to use their natural resources. That said, the wording towards the end of the provision is a reference to the obligation to protect and preserve the marine environment as expressed in Article 192 and might suggest that the earlier article has priority over the sovereign right of exploitation.15 These two articles, however, lack sufficient detail to provide meaningful guidance to states as to what activities are acceptable under the convention. An attempt to address this is made by the LOSC through the terms of Article 194. The first four parts of this article address pollution and will be considered in the following section. This does mean that much of the detail set out in Article 194 is of limited relevance for pushing MPA strategies.16 However, Article 194(5) states: The measures taken in accordance with this Part shall include those necessary to protect and preserve rare or fragile ecosystems as well as the habitat of depleted, threatened or endangered species and other forms of marine life. Interpreting this provision is far from straightforward. Opinions differ as to whether Article 194(5) emphasises one of the objectives of pollution control,17 or whether it creates a wider obligation to take conservation measures to protect and preserve rare or fragile ecosystems from all threats (i.e. not limited to pollution).18 This uncertainty stems from inconsistent features of the article. The quoted provision is contained in an article given the heading ‘Measures to prevent, reduce and control pollution of the marine environment’, yet it refers to measures to be taken in accordance with ‘this Part’. This latter wording appears to be a reference to Part XII of the LOSC, which, if it is recalled includes Articles 192 and 193, is not limited to pollution control.19 If the wider interpretation is favoured, then Article 194(5) is important as it can be argued that it draws particular attention to coral reef ecosystems needing protection. This is because, although no particular habitat types are specified, reference is made to ‘rare or fragile ecosystems’. Coral reefs might well be regarded as fragile given the complexity of the relationships which sustain the ecosystem and their vulnerability to a range of threats. That said, and whilst it does not rule them out as a possible measure, this part of Article 195 does not explicitly push MPAs as a strategy for conserving rare or fragile ecosystems. Thereafter the focus of Part XII remains on the control of pollution. Those articles that are not pollution focused, such as Article 202 (on scientific and technical assistance to developing states), Article 196(1) (on the introduction of alien species) and Article 206 (on the assessment of potential effects of activities), only have a general bearing upon the protection and preservation of marine habitats. Thus explicit reference to MPAs is omitted. The reason for this may well lie in the ultimate form of the LOSC as a hybrid convention, which is at once a framework document providing a constitutional structure for the legal order of the seas, and in other respects a detailed convention on matters such as pollution. Robin Churchill and Vaughan Lowe therefore characterise the agreement as in places: an extremely precise, detailed instrument closer in appearance to a commercial contract or concession than to an international treaty . . . The other parts are more in the nature of a framework treaty or loi-cadre, leaving the elaboration of precise rules to other bodies, such as national governments and international organisations, and to dispute settlement procedures or future international negotiations.20 In support of the latter point, attention should be drawn to Article 197, which provides: States shall cooperate on a global basis, and as appropriate, on a regional basis, directly or through competent international organisations, in formulating and elaborating international rules, standards and recommended practices and procedures consistent with this Convention for the protection and preservation of the marine environment, taking into account characteristic regional features. It is therefore apparent that in Part XII the negotiating parties have left only a general framework of provisions with a small impact upon the conservation of coral reef ecosystems through MPAs. Consequently, the LOSC envisages that interested parties must look outside of its provisions for the formulation and elaboration of international rules, standards and recommended practices. The MEAs considered in the following chapters, as well as the regional agreements discussed later in this chapter, are potentially the more significant for MPAs and coral reef conservation. Questions will therefore inevitably arise concerning the relationships between the LOSC and pre-existing or subsequent treaties. This is an area that is duly dealt with under the 1969 Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties,21 although ideally such issues are better dealt with through dedicated treaty provisions.22 The LOSC adopts the latter approach and addresses the relationship of Part XII to external MEAs in Article 237. This provision provides that Part XII preserves the obligations of states under previously agreed conventions relating to the protection and preservation of the marine environment, and countenances those undertaken subsequently under conventions concluded in furtherance of the general principles of the LOSC. The only proviso is that these obligations should be carried out in a manner consistent with the general principles and objectives of the LOSC. Perhaps one of the more significant effects of this provision is that it maintains the importance of the maritime zones with respect to powers and duties of coastal and third party states. Thus, a subsequent agreement such as the 1992 Convention on Biological Diversity might encourage the designation of MPAs, but only in a manner consistent with the powers of coastal states applicable in the maritime zones in which the MPA will be located. These powers were explored in full in the previous chapter. Indeed as will be seen, the Convention on Biological Diversity explicitly subordinates itself to the ‘law of the sea’, which can be assumed to include the LOSC.23 The framework approach of these provisions from a coral reef and MPA perspective is therefore supported by the provisions on the relationship between the LOSC and other conventions. It also perpetuates the LOSC’s reduced significance for enclaves and the importance of other conventions for promoting MPAs for the conservation of coral reefs. The LOSC made important changes to the international law of fisheries. Indeed, the freedom for any nation to fish in the most productive parts of the sea (the shallows within 200 nautical miles of the coast) was formally replaced with coastal state authority and control over fisheries management.24 The effect was to bring almost 90 per cent of commercial fisheries within single state control.25 The convention made such progress through the expansion of territorial sovereignty and sovereign rights. It attributed jurisdiction over resources to states by reference to the various maritime zones that were either enlarged (in the case of the territorial sea) or formally recognised, as per the EEZ and archipelagic waters. This left a single decision-making authority with competence over all marine resources and habitats.26 Whilst this has curtailed multi-state freedom of fishing and therefore, supposedly, averted the environmental problems associated with the ‘tragedy of the commons’,27 the extension of jurisdiction has so far failed to prevent over exploitation of marine resources and damage to marine habitats. As was described in the previous chapter, within the internal waters, territorial sea and any archipelagic waters, the coastal state exercises territorial sovereignty. With the exception of navigational rights28 and the traditional fishing rights of states neighbouring archipelagic nations,29 this means that coastal and archipelagic states enjoy full authority to enact and enforce their own fisheries laws and regulations. Access to marine resources in these zones by any other state therefore requires authorisation. There are few constraints, consequently, upon the coastal and archipelagic states’ fisheries policies. They can use the resources largely as they like, including selling permits for fishing in these waters to foreign enterprises. What is more, unlike in the EEZ, there is no obligation under the LOSC demanding that the state conserve or optimally utilise the resources in these zones.30 Admittedly, the obligation under Article 192 to ‘protect and preserve the marine environment’ imposes some form of constraint upon the coastal and archipelagic states,31 but the generality (and therefore the problems) with this provision have already been highlighted. The LOSC does little to circumscribe the freedom of these states. Indeed, capacity and practicality are probably the greatest ‘brakes’ upon state control. For instance, if the state does not have the capacity to police these waters (which in the case of archipelagos may be extensive), then infringements will go undetected.32 As a result, the only other international legal constraints placed upon the policies of coastal and archipelagic states with respect to fisheries and marine resources are those that flow from voluntary ratification or accession to environmental treaties. Thus the 1992 Convention on Biological Diversity33 and the 1972 Ramsar Convention on Wetlands of International Importance34 may constrain state action for coastal states who are contracting parties to these agreements. The observations made in relation to other MEAs in this study, therefore, will have a far greater impact than the LOSC upon the freedom of states to utilise marine resources and upon marine ecosystem conservation policies in these maritime zones. This fact carries added significance given the likely predominant location of coral reefs in these waters. Perhaps the main development in terms of international law governing fisheries management under the LOSC was the recognition of the EEZ.35 Rather than having territorial sovereignty within this area, the coastal state has sovereignty over particular matters or activities. This includes the protection and preservation of the marine environment, and the exploitation, exploration, conservation and management of marine living resources.36 With respect to the latter, whilst it is left to the coastal state to set allowable catch levels within the zone,37 their freedom is partially constrained. They must take proper conservation and management measures to ensure the resources are not over-exploited and populations of harvested species are maintained or returned to a level that supports maximum sustainable yield.38 These measures must also take account of the effects on species that are associated or dependent upon harvested species, so that the population levels of these dependent or associated species remain above the level where their capacity to reproduce is not seriously threatened.39 These limits imposed under Article 61 supposedly safeguard the wider global community’s interest in protecting marine species against over-exploitation.40 What is more, the coastal state is supposed to give access to fishers from other countries if their own needs do not exhaust the annual catch limit.41 However, this need not create undue demands or undermine any environmental initiatives voluntarily pursued by a coastal state. As Burke has observed, ‘allowable catch does not mean . . . a quantity of fish determined by objective, scientific criteria, leading to the maximum harvest of fish’.42 Article 61(3) allows catch levels to reflect economic and environmental factors, such that it has been observed that the coastal state has so much discretion that practically any level of catch can be legitimately set.43 And of course, setting limits according to broader environmental policies is supported by the sovereign right of states in the EEZ to implement such policies in this zone.44 Further, coastal state policies are supposed to protect and preserve the marine environment as per Article 192. Nevertheless, thereafter, there is little international legal control of fisheries policy unless the coastal state undertakes additional duties under other MEAs. This is particularly so with regards to the promotion of coral reef conservation. New treaties have followed on from the LOSC provisions on fishery regulation, but these have been needed to ensure cooperation over species that migrate between EEZs and the High seas, or between the EEZs of two coastal states.45 These are all of limited relevance for coral reefs. The LOSC has left much power in the hands of coastal states to manage and regulate fisheries, without imposing many constraints upon their possible activities. One response to this gap has come from the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO), which has produced and disseminated the voluntary Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries.46 However, even in relation to those small limits that have been introduced under the LOSC, doubts continue to be expressed about their environmental credentials. For example, the recognition of the EEZ has enclosed large areas of the oceans and led to the distribution of authority over resources to a single state. But this responsibility and control has not necessarily ensured the formulation of national policy and management systems that adequately protect marine habitats and ecosystems such as coral reefs.47 Perhaps it is simply unrealistic to expect states to have the capacity (when setting catch levels for the EEZ) to extrapolate the effects of fishing for one species upon others within the complex coral reef ecosystem.48 Fundamentally, and this applies to both fisheries regulation and the previous discussion on the promotion of MPAs, the enclosure of the oceans by reference to maritime zones reflects, in de Klemm’s words, ‘political rather than ecological boundaries’.49 For Burke, ‘ecosystems are ecological, not political, concepts, and do not fall naturally within artificially conceived marine regions. Those who contend that the treaty supports ecosystem management are without justification converting an obstacle to such management into a basis for it.’50 Fortunately, greater sensibility to the ecological needs of reefs can more often be found under the other MEAs considered in this book. In 1972, the Stockholm Declaration called for states to take all possible steps to prevent pollution of the sea.51 This shaped subsequent international efforts to tackle marine pollution. For the LOSC this influence can be seen most obviously in the convention’s definition of pollution of the marine environment, which draws heavily upon the declaration’s wording. Marine pollution is: the introduction by man, directly or indirectly, of substances or energy into the marine environment, including estuaries, which results or is likely to result in such deleterious effects as harm to living resources and marine life, hazards to human health, hindrance to marine activities, including fishing and other legitimate uses of the sea, impairment of quality for use of sea water and reduction of amenities.52 The biggest sources of such pollution are sewage, industrial waste and agricultural run-off, which all share land-based origins.53 Indeed, in 1990, the Joint Group of Experts on the Scientific Aspects of Marine Environmental Protection (GESAMP) reported that 44 per cent of marine pollution came from direct discharges from land, and 33 per cent from the atmosphere (again the majority of that emanating from land sources).54 In comparison, vessel-source pollution accounted for 12 per cent, dumping of waste for 10 per cent and seabed activities just 1 per cent.55 Some of this imbalance may be due to legal initiatives. The latter group of pollution sources have been tackled via international standard setting since the mid-twentieth century, leading to the problems diminishing; land-based sources of pollution (hereinafter ‘LBSP’) have not been so carefully regulated and their impacts have become increasingly severe.56 This leaves LBSP as a major concern and source of pollution, with negative impacts continuing to affect coral reefs, as described at the start of this book. What is more, states have shown little inclination or will to agree international laws for the regulation of this source of pollution, preferring a blend of non-binding programmes of action, guidelines and (as will be shown later in this chapter) occasional multilateral agreements of regional application. Following the establishment of UNEP to implement the Stockholm Declaration, this new body preferred to focus efforts upon regional agreements to tackle LBSP and leave any global legal instrument to simply set out a framework of guidelines and principles.57 The drafting of Part XII of the LOSC must be seen in this light. Thus under Article 194(1) contracting parties: shall take, individually or jointly . . . all measures . . . that are necessary to prevent, reduce and control pollution of the marine environment from any source, using for this purpose the best practicable means at their disposal and in accordance with their capabilities. Article 194(3) then highlights specific types of marine pollution that are to be dealt with by states, including vessel source, seabed exploration and ‘the release of toxic, harmful or noxious substances, especially those which are persistent, from land-based sources, from or through the atmosphere . . .’. Of course, Article 194(5) remains applicable in the context of the call to address LBSP, thereby drawing some attention towards the need for measures to protect or preserve fragile and rare ecosystems. Later in Part XII, the convention singles out each cause of pollution. Article 207 covers LBSP. The main feature of this provision is the obligation for states to ‘adopt laws and regulations to prevent, reduce and control pollution of the marine environment from land-based sources . . . taking into account internationally agreed rules, standards and recommended practices and procedures’.58 This is to include pollution entering the marine environment via ‘rivers, estuaries, pipelines and outfall structures’.59 Since the LOSC does not itself set internationally agreed rules, standards and recommended practices and procedures, Article 207(4) calls on states to endeavour to establish these separately taking due account of regional variations as well as developing states’ capacities and developmental needs.60 Notably, this allowance for capacity and developmental needs is not present in the articles relating to the other sources of pollution, reflecting the perceived economic costs and developmental sacrifices that are needed to tackle LBSP.61 Thereafter the article serves to remind states that they may also need to take non-legal and non-regulatory measures as necessary, and that they should harmonise their policies at the regional level.62 Coral reefs do not receive explicit mention. Given the framework nature of the LOSC’s approach to LBSP, and its call for states to endeavour to establish more precise rules, standards, practices and guidelines under Article 207(4), a degree of impetus was generated post 1982 towards negotiating some form of global instrument on the issue. This initially produced the Montreal Guidelines; a checklist of basic measures recommended for inclusion in future MEAs on LBSP.63 Although the guidelines do not mention coral reefs, they do include a recommendation that MPAs be established to protect and preserve ‘unique or pristine areas, rare or fragile ecosystems, critical habitats and the habitat of depleted, threatened or endangered species and other forms of marine life’.64 Nevertheless, by 1990 GESAMP was still reporting the dominance of LBSP as a contributor to marine pollution;65 a fact repeated two years later in Agenda 21.66 Agenda 21 went on to remind states of their responsibilities flowing from the LOSC to prevent, reduce and control degradation of the marine environment.67 Amongst other things, Agenda 21 called for the strengthening or extension of the Montreal Guidelines, and UNEP was asked to convene an intergovernmental meeting on LBSP.68 The result of the latter call was a global conference held in Washington DC in late 1995. This conference established the Global Programme of Action for the Protection of the Marine Environment from Land-Based Activities (GPA).69 The GPA remains to this day the principal global multilateral framework for addressing LBSP. Its stated aim is to be a source of ‘conceptual and practical guidance’ to facilitate the realisation of the duties of states under the LOSC to protect the marine environment.70 The programme itself, though, is legally non-binding. Under the GPA, states are encouraged to draw up national action programmes that integrate land-use, river basin and coastal management.71 A number of recommended actions are set out in the GPA for producing these programmes, including assessing and identifying areas of particular concern such as coral reefs.72 The GPA goes on to describe the impact of particular types of LBSP, and sets out ways to prevent harmful impacts. In this context the programme emphasises the impact of these forms of pollution on coral reefs, in particular calling for: (a) sewage outfalls to be located so that they do not overload coral reefs with nutrients,73 (b) improved control of human activities that cause siltation that buries and threatens coral reefs74 and (c) safeguarding (and restoring) coral reefs in the face of coastal construction projects.75 The GPA draws particular attention, therefore, to the major types of LBSP that threaten coral reefs. This has been supplemented by the GPA’s own subprogramme on ‘Physical Alteration and Destruction of Coastal Habitats’, which focuses upon protecting coastal habitats (with explicit reference being made to coral reefs) by strengthening national legislation, and safeguarding ecosystems through integrated coastal management, with site-specific action being developed where needed.76 Since the GPA’s adoption, two intergovernmental meetings have been convened to assess progress and to adopt work plans for periods between these meetings. The first was held in late November 2001 in Montreal. In the six years since the programme’s foundation, implementation by states was mixed. Some national action programmes had been established, whilst there were also signs of increasing use of integrated coastal management and environmental impact assessments.77 Nevertheless, those in UNEP and the GPA coordination office still felt that there had been little concrete action for a wide variety of reasons, including lack of political will for implementing the GPA, lack of finance, poor enforcement, and national institutional disconnects between freshwater, coastal and marine managers.78 Klaus Töpfer (then the executive director of UNEP) indicated that there existed the technology and resources around the world to tackle LBSP, but that it needed solidarity, cooperation and political will to turn planning into action.79 The second intergovernmental meeting recorded good progress in terms of over 60 states adopting action programmes and significant funding streams for GPA-linked projects provided by the Global Environment Facility (GEF).80 However, other reports indicated that sewage and nutrient pollution was worsening.81 Sewage was a growing problem as populations continued to increase and sanitation facilities remained prohibitively expensive.82 Indeed, around 90 per cent of sewage generated in developing countries was thought to be discharged untreated into rivers and coastal waters.83 With the exception of the 2001 Convention on Persistent Organic Compounds,84 and given that the GPA falls well short of amounting to a binding global agreement, no MEA on LBSP has been felt to be necessary or desirable. States have tended to deflect calls for a global agreement (preferring regional agreements if any) since LBSP present in a variety of forms and can be complicated by geographic factors that arise in different parts of the world. As a justification for protocols under the regional seas programme (described below) there is evident sense in this. It has also been argued that there is little evidence to suggest LBSP degrade the maritime waters of other states or the high seas; the pollution impacting upon coastal waters under source state jurisdiction.85 These arguments suggest that LBSP are a national, rather than international, problem which do not merit a global legal agreement. But such arguments are weak as they ignore the common concern of all humankind in the conservation of biological diversity and ecosystems such as coral reefs. Perhaps the biggest reason for resisting international obligations and preferring voluntary undertakings is the concern amongst nations regarding the likely costs to industry, agriculture and municipalities from being obligated to reduce emissions from land.86 As Patricia Birnie and others conclude, the sceptical view ‘is that once again economic and industrial priorities have prevailed’. Thus states negotiated allowance for development needs into the LOSC87 and the GPA, the latter of which expressly permits variable prioritisation of LBSP as an issue within domestic governance.88 Thus the GPA stands alone as a dedicated multilateral response. However, whilst the GPA duly highlights and calls for action to tackle the types of LBSP that cause reef degradation (and for that it is to be commended), there is little evidence to suggest that the current arrangement is stemming the negative impacts of LBSP upon coral reefs in the face of growing coastal populations and urbanisation.89 It is quite possible that the non-legally binding status of the programme is hindering greater success in this respect. Whilst there is action under the GPA, it is telling that one of the main difficulties has been getting the issue of LBSP integrated across all sectors of government and developmental planning. This suggests the GPA has so far failed to sufficiently realign the conduct and priorities of governments to favour conservation over pollution, to the ultimate detriment of coral reefs. As David VanderZwaag and Ann Powers observe, the GPA simply does not provide a mechanism to ensure action.90 With lack of political will as one of the major factors driving reef degradation,91 this is clearly a concern. Under Article 197 of the LOSC: States shall cooperate on a global basis and, as appropriate, on a regional basis, directly or through competent international organisations, in formulating and elaborating rules, standards and recommended practices and procedures consistent with this Convention, for the protection of the marine environment, taking into account characteristic regional features. During the negotiations for the convention – indeed up until 1976 – the text of this article had only referred to cooperation for the prevention of marine pollution. At the 4th session of the negotiations this was changed so as to cover the wider task of protecting the marine environment.92 As has previously been discussed, this provision complements the framework character of the LOSC. It supports externally concluded MEAs between states, enabling the creation of more focused and detailed obligations. Further, such conventions are envisaged as including those operational at the regional, as well as the global, level. Those regional initiatives that are currently active therefore merit consideration, particularly where they have led to the conclusion of legal agreements.93 However, it would be inappropriate to view the LOSC as the origin of regional seas initiatives. In 1969 an agreement was concluded in Bonn for dealing with pollution of the North Sea by oil and other harmful substances,94 whilst the two precursor treaties to the 1992 OSPAR Convention (which covers the North-East Atlantic, the North Sea and adjacent Arctic waters) were concluded in the early 1970s.95 In addition, after its establishment in 1972, UNEP built upon its role in developing an action plan and agreements for the Mediterranean by endorsing a Regional Seas Programme in 1978.96 As an approach to dealing with the marine environment, regional arrangements therefore pre-date both the beginnings of negotiations for and the conclusion of the LOSC. Indeed, Charles Okidi notes that with ten regional agreements already in place, Article 197 of the LOSC might be viewed as the codification of an existing practice.97 Many of the world’s tropical maritime areas where coral reefs flourish are covered by a regional programme. These regions are identified in the first column in Table 1. As is clear from the second column, all but a few of the nations endowed with coral reefs participate in one or more of these regional initiatives.98 Where they can be agreed, regional conventions have traditionally received widespread support for the particular advantages they are thought to offer over global MEAs.99 Frequently cited in support of this position is the point that regional agreements can improve the ability of states to react to pollution events through the creation and coordination of regional emergency response centres. Additionally, these treaties permit the adoption of rules more adapted to local needs100 and in particular allow pollution regulation to be tailored to regional characteristics and threats. For example, states located close to sea lanes used by oil tankers will be concerned with discharges from these vessels, whilst industrialised coastal states might have particular needs to tackle land-based sources of pollution.101 Other points unrelated to pollution have also been advanced to support regional agreements. Okidi, for example, argues that they are better at engaging states and inducing cooperation and commitment in matters of specific relevance to that state and area.102 He goes on to suggest that regional agreements are more acceptable and amenable to states who are uncomfortable with the creation of global super-agencies under international MEAs,103 but who equally acknowledge that unilateral action is an unattractive proposition.104 The peace of mind thereby engendered by regional treaties makes their negotiation conducive to agreeing more exacting commitments. Table 1 States engaged in regional initiatives with jurisdiction over coral reefs in the region

4 United Nations Convention

on the Law of the Sea and

the regional seas

agreements

1 Introduction to protection of the marine environment under the law of the sea

2 The Convention on the Law of the Sea and the promotion of marine protected areas

3 Fisheries regulation

3.1 Territorial sovereignty

3.2 Sovereign rights

3.3 Summary of fisheries regulation under the LOSC

4 Land-based sources of pollution and coral reef conservation

4.1 Provisions of the LOSC on land-based sources of pollution

4.2 Developments post-adoption of the LOSC

4.3 Conclusions

5 Regional seas governance

5.1 Background to the regional seas initiatives

5.2 The appropriateness of regional initiatives

| Region | States |

| Wider Caribbean | Antigua & Barbuda, Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominica, Dominican Republic, France, Grenada, Haiti, Honduras, Jamaica, Mexico, Netherlands, Nicaragua, Panama, St Kitts & Nevis, St Lucia, St Vincent & the Grenadines, Trinidad & Tobago, UK, USA and Venezuela. |

| Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden | Djibouti, Egypt, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sudan and Yemen. |

| ROPME Sea Area | Bahrain, Iran, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates. |

| Eastern Africa | Comoros, France, Kenya, Madagascar, Mauritius, Mozambique, Seychelles, Somalia, South Africa and Tanzania. |

| West & Central Africa | Equatorial Guinea and Guinea. |

| South Asian Seas | Bangladesh, India, Maldives and Sri Lanka. |

| East Asian Seas | Australia, Cambodia, China, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam. |

| North-East Pacific | Columbia, Costa Rica, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua and Panama. |

| South-East Pacific | Columbia, Ecuador and Panama. |

| South Pacific | Australia, Cook Islands, Federated States of Micronesia, Fiji, France, Kiribati, Marshall Islands, Nauru, New Zealand, Niue, Palau, Papua New Guinea, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tonga, Tuvalu, USA and Vanuatu. |

| North-West Pacific | China and Japan. |

To these apparent advantages should be added the practical consequence that participation by contracting states ought to be practicably easier and cheaper under regional initiatives. Meetings are more likely to be closer to a state party’s territory with the associated saving in travel costs; an important factor for the developing countries in which the majority of coral reefs are located. The exception to this seems to be the South Pacific region, where island states are separated by greater distances and the international transport links less extensive.105

However, embracing regional initiatives and agreements for the conservation of coral reef ecosystems has drawbacks. For example, regional political tensions may be more apparent within the smaller fora operating under such initiatives, as opposed to being dissipated in the large-scale proceedings of global meetings.106

Perhaps more fundamentally, the appropriateness of regional agreements and action plans for conserving and protecting coral reef ecosystems may be questioned as a matter of principle. As already described, the international community has an interest in the conservation of coral reef ecosystems and all states have a duty to conserve these habitats under the principle of the common concern of humankind.107 Action taken by the parties to regional agreements will undoubtedly have the potential to contribute to the conservation of coral reef ecosystems in accordance with the international community’s interest. The difficulty is ensuring that these measures are exposed to the scrutiny and opinions of all those who, because of the principle of common concern, are recognised as having legitimate standing and interest in the issue. Problematically, membership of regional initiatives and conventions may by design, or as a result of practice, operate within a select group of countries. For example, this is the case for the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden agreement, where only states invited to the conference of plenipotentiaries that negotiated the convention, and Arab League member states, may become contracting parties.108 It is this that seems so fundamentally at odds with common concerns.

It is therefore important to encourage the involvement of the international community in alternative ways given the limitations on the make-up of contracting parties. For example, the regional agreements could actively participate and be encouraged to engage with the global MEAs. In particular, given the scale of its engagement with the global community, regional secretariats could attend conferences of the parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity in order to report on their work and field enquiries. Only a few are currently taking such steps, namely the Mediterranean and South Pacific regions.109 Conversely, secretariats of the global MEAs, international NGOs or even non-party states could be encouraged to attend conferences of the parties to the regional agreements. Whether this is already a widespread practice is far from clear given the difficulty in obtaining records of such conferences, but examples can be found of Greenpeace and the Ramsar Secretariat attending meetings convened under the convention and protocols applicable in the Wider Caribbean region.110 Indeed, a Memorandum of Cooperation exists between the Ramsar Convention and these Caribbean agreements, specifically providing for collaboration where coral reefs are recognised and conserved under these MEAs.111