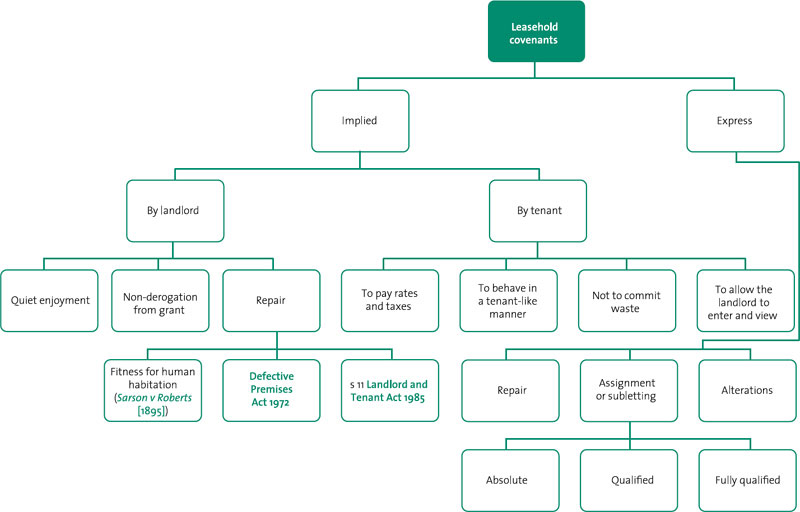

Leasehold Covenants

All leases contain covenants: promises contained within the lease that the landlord or tenant will carry out, or refrain from carrying out, certain acts in respect of the leasehold property. These covenants could cover anything from a covenant by the tenant to pay rent, or to keep the premises in repair, to a covenant by the landlord to insure the property.

Leasehold covenants can be either expressly contained within the lease, or implied into the lease under common law or by statute.

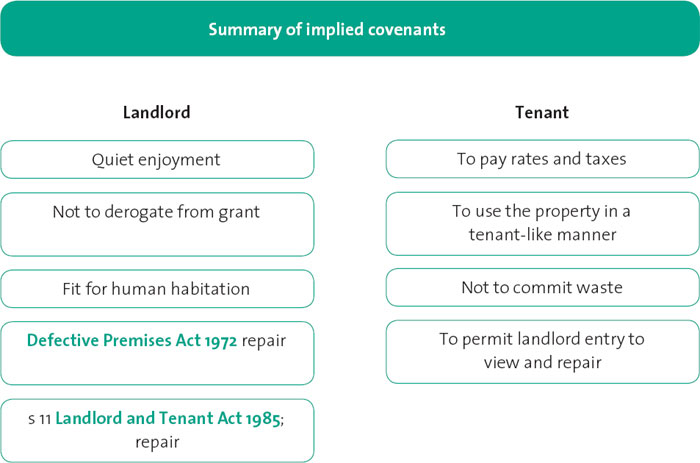

Implied covenants

By the tenant

To pay rates and taxes

At common law there is an implied covenant on the part of the tenant to pay all rates and taxes payable on the property.

To use the property in a tenant-like manner

This is a very basic common law obligation to look after the property in a general fashion, but one which does not extend to the repair of the property. It might include things such as turning off the water if the tenant is going away, cleaning the chimneys and the windows, mending the electric light when it fuses and unblocking the sink when it is blocked by his waste (Warren v Keen [1954]).

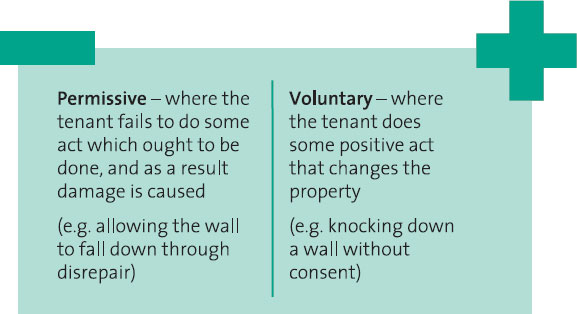

Not to commit waste

This is where the tenant has carried out an unauthorised act or an omission which physically alters the state of the land. Waste can be:

If there is nothing in the lease to the contrary, all tenants are liable for voluntary waste (Yellowly v Gower (1855) 11 ExD 274). However, the extent of liability for permissive waste depends on the type of lease. A tenant of a fixed-term lease will always be responsible for permissive waste, unless the lease states otherwise; but the liability of a periodic tenant will depend on the length of the periodic term. Generally speaking, the shorter the term is, the less onerous the tenant’s responsibility.

To allow the landlord to enter and view

Where the landlord has either an implied or express obligation to repair, there is an implied obligation on the tenant to allow the landlord access to the premises to inspect them and carry out necessary repairs (Mint v Good [1951] 1 KB 517).

By the landlord

Quiet enjoyment

At common law, every tenant has the benefit of a covenant implied into their lease that the landlord will not breach the tenant’s quiet enjoyment of the premises; in other words, the tenant will be allowed by the landlord to occupy the premises undisturbed.

A breach of quiet enjoyment must amount to an actual disturbance of the tenancy: actions by the landlord that cause a mere inconvenience to the tenant will not be sufficient to amount to a breach in this context.

Case precedent – Browne v Flower [1911] 1 Ch 219

Facts: The landlord built an external staircase outside the tenant’s premises which affected the tenant’s privacy. Held: There was no breach of the tenant’s quiet enjoyment, as the landlord had done nothing to prevent or hinder the tenant in her ordinary use of the property.

Principle: A mere inconvenience to the tenant will not amount to a breach of quiet enjoyment.

Application: Use the facts of this case to support your argument that a breach of quiet enjoyment must amount to an actual disturbance of the tenancy.

Common Pitfalls

A covenant of quiet enjoyment does not usually relate to noise made by the landlord, although it may do if the noise is continuous and excessive to the point where the tenant is prevented from enjoying the use of the property (Southwark LBC v Mills [1999] 4 All ER 449).

Not to derogate from grant

The landlord, having let the premises for a particular purpose, cannot then do anything that would prevent them from being used for that same purpose (Southwark Borough Council v Mills).

Case precedent – Harmer v Jumbil (Nigeria) Tin Areas Ltd [1921] 1 Ch 200

Facts: A landlord let a warehouse to a tenant to store explosives, for which he required a licence. One of the terms of the licence was that there were to be no other buildings within a certain radius of the storage unit. The effect of this was that the landlord was prevented, under the implied covenant of non-derogation from grant, from building within that radius.

Principle: The landlord, having let the premises for a particular purpose, cannot then do anything to frustrate that purpose.

Application: Use this case as an example of derogation from grant by the landlord.

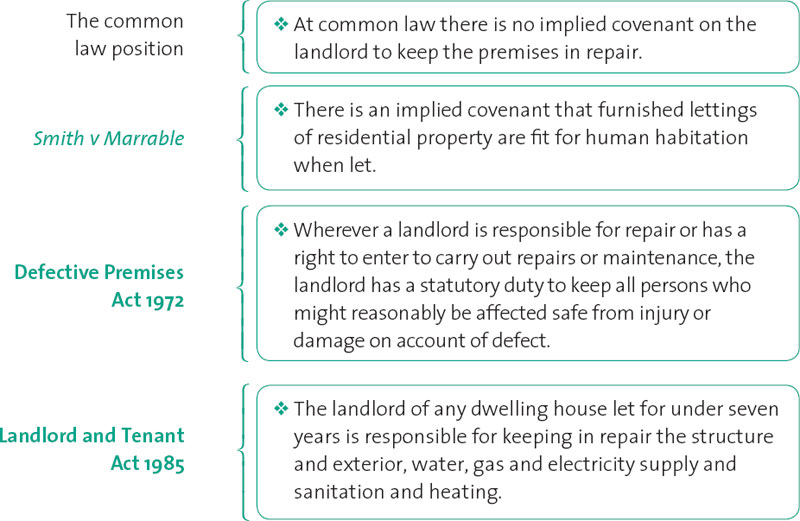

Repair

At common law there is no implied covenant on the landlord to keep the premises in repair; however, there are a number of limited circumstances in which covenants relating to repair will be implied on the landlord, either at common law or by statute. These are as follows.

Fitness for human habitation

There is an implied covenant at common law in respect of furnished lettings of residential property that the premises will be fit for human habitation when they are let (but not subsequently – see Sarson v Roberts [1895] 2 QB 395).

Case precedent – Smith v Marrable (1843) 11 M&W 5

Facts: A landlord had let a property to a tenant, which turned out to be infested with bugs. The property was found not to be fit for human habitation and the tenant was held by the court to be entitled to quit the premises immediately without giving notice under the lease.

Principle: A furnished letting of residential property must be fit for human habitation when let.

Application: Compare this case with the facts in your own scenario to determine whether or not the property is fit for human habitation.

Defective Premises Act 1972

Wherever a landlord is responsible for the repair of a building, or if they have a right to enter leased premises to carry out repairs or maintenance, then a statutory duty will be implied for the landlord to keep ‘all persons who might reasonably be expected to be affected by defects in the premises’ reasonably safe from injury or damage on account of defects in the property (s 4 Defective Premises Act 1972). The obligation applies in respect of any person either visiting or occupying the premises.

The duty applies wherever the landlord either knows about the defect or ought to have known about it. It is therefore up to the landlord regularly to check the condition of the building and keep up with repairs.

There will be no liability if the damage or lack of repair was outside the scope of the landlord’s duties, however (McNerny v Lambeth LBC [1989] 1 EGLR 81).

Case precedent – Clarke v Taff Ely Borough Council (1980) 10 HLR 44

Facts: A woman fell from a table whilst redecorating because the table leg went through a rotten floorboard. Held: The landlord was liable. The age and construction of the house was such that it had been reasonably foreseeable that the floors in the building might rot due to dampness. He should therefore have carried out regular inspections of the property and undertaken a structured programme of maintenance in respect of it.

Application: Use this case to illustrate the type of injury for which a landlord will be responsible under the Defective Premises Act 1972.

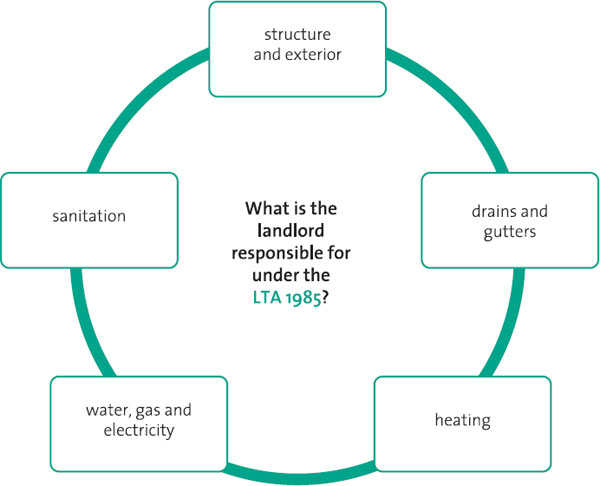

Landlord and Tenant Act 1985

The landlord of any dwelling house let for a period of less than seven years shall be responsible for keeping in repair the structure and exterior (including drains and gutters) of the property, and to keep in repair and proper working order the installations in the house for the supply of water, gas and electricity and for sanitation and heating (s 11).

Contrary to the position under the Defective Premises Act 1972, the landlord’s obligation under the Landlord and Tenant Act 1985 does not arise until the landlord is notified of the disrepair. Once notice has been received, the landlord must carry out any necessary repairs within a reasonable time (O’Brien v Robinson [1973] 2 WLR 393).

The structure of the dwelling house is not confined to the load-bearing structure, but rather it ‘consists of those elements of the overall dwelling-house which give it its essential appearance’. This means that the landlord’s liability will extend to the repair or replacement of windows and doors, but will not include the redecoration of the exterior, unless this is necessary in order to keep the property wind- and water-tight (Irvine’s Estate v Moran [1992] 24 HLR 1).

Keeping the premises in repair does not extend to the rectification of an inherent defect in the property’s design:

Case precedent – Quick v Taff-Ely BC [1986] QB 809

Facts: The original house meant that the house suffered from condensation. Held: The council was not liable under the 1985 Act. There was no actual disrepair to the building; rather, the damage was the product of a simple design defect in the house.

Principle: Keeping the premises in repair does not extend to the rectification of an inherent defect in the property’s design.

Application: Use this case to show the difference between a design defect and a lack of repair, under the Landlord and Tenant Act 1985.

As for the term ‘proper working order’, this means that the water and other installations in the house are in good mechanical order; in other words, that they are in proper working condition.

Case precedent – Wycombe HA v Barnett (1982) 47 P&CR 394

Facts: A failure on the part of the landlord to lag the water pipes was not considered by the court to be a breach of his statutory duty to repair under the Act. If the water pipe had burst due to being rusted away, this would have fallen within the remit of the landlord’s repairing obligations, but for it to burst through freezing could not in all reasonableness be said to constitute a lack of repair.

Principle: ‘Proper working order’ means in proper working condition and does not extend to a fuse blowing or pipes freezing.

Application: Compare this case to the facts in your own scenario to show the extent of the repairing obligation under the LTA 1985.

Points to remember about covenants to repair

Summary of implied covenants

Those you are most likely to come across are express covenants to repair, covenants not to assign or sublet, covenants to use for a particular purpose or covenants not to make alterations to the premises.

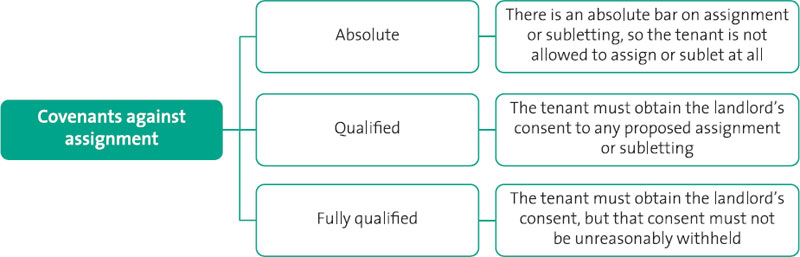

Not to assign or sublet

The landlord will usually make specific provision in the lease to deal with restricting assignment or subletting. The landlord may make the tenant’s covenant against assignment or subletting ‘absolute’, ‘qualified’ or ‘fully qualified’.

It should be noted that a qualified covenant against assignment or subletting in the lease will be automatically converted into a fully qualified covenant under the provisions of s 19(1) of the Landlord and Tenant Act 1927.

On receiving a request to assign or sublet, the landlord must respond in writing to any request to assign or sublet within a ‘reasonable time’, giving reasons for their refusal if applicable (s 1(3) Landlord and Tenant Act 1988). Following NCR Ltd v Riverland Portfolio No. 1 Ltd (No. 2) [2005] 2 EGLR 42, a common-sense approach will be taken by the courts when determining what is a reasonable time: essentially, the landlord should act as quickly as is reasonable to do so under the circumstances.

The reasons for refusal to a proposed assignment or subletting must also be reasonable. What is and is not will not be limited to a set of particular circumstances, but should be judged on the facts of each individual case (Bickel v Duke of Westminster [1977] QB 517).

Consent will automatically be deemed to have been unreasonably withheld if the landlord withholds consent on grounds of colour, race, ethnic or national origins or sex. This is in accordance with s 24 Race Relations Act 1976