Adverse Possession

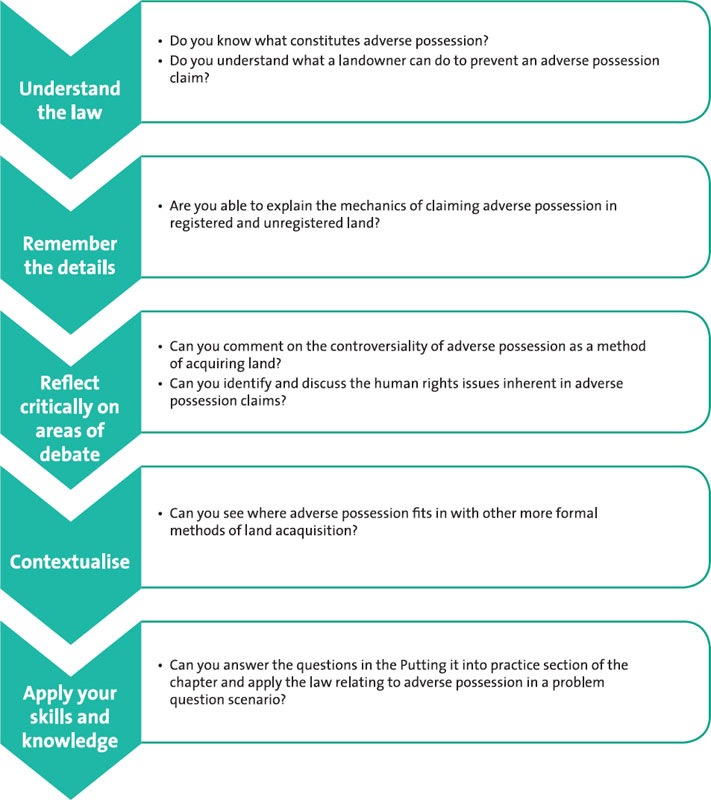

Revision objectives

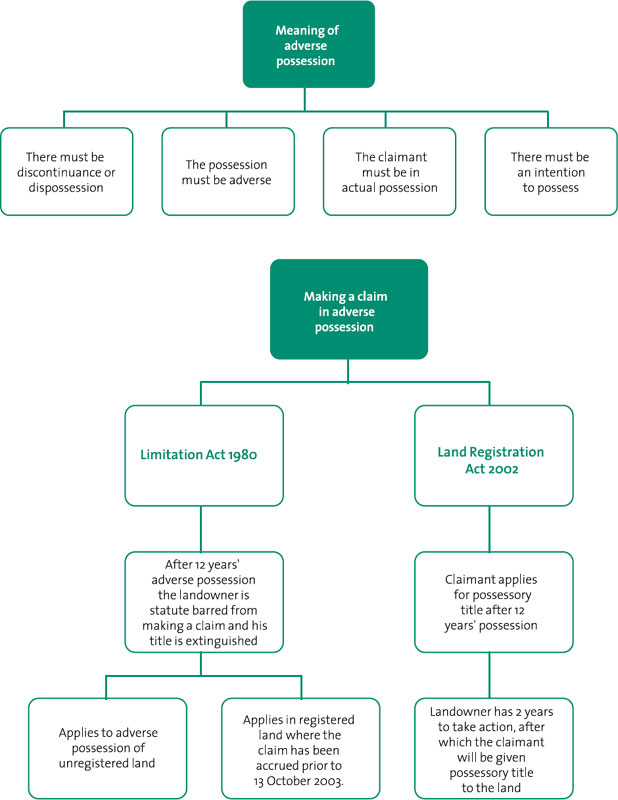

Adverse possession is a means of acquiring land belonging to another person by occupying, or ‘possessing’, that land for an extended period of time.

Understanding: what constitutes adverse possession

Dispossession or discontinuance

A claim for adverse possession starts from the time the legal owner of the land is either dispossessed of the land, or discontinues their possession of it (Limitation Act 1980, Sched 1, para 1 and LRA 2002, Sched 6, para 1).

‘… [dispossession] is where a person comes in and drives out the others from possession, [discontinuance] is where the person in possession goes out and is followed into possession

Per Fry J, Rains v Buxton (1880) 14 Ch D 537

Proving discontinuance is difficult and, unless the landowner has physically cut themselves off from their own property, in most cases the squatter will be viewed as having dispossessed the landowner through their occupation of the property.

Case precedent – Powell v McFarlane (1979) 38 P&CR 452

Facts: The claimant had fenced off a Christmas tree plantation. The landowners visited the land infrequently and their inspections of it were of a cursory nature, often consisting of the landowner viewing the property from the road whilst remaining seated in their car. Held: The land had not been abandoned; rather, the squatter had dispossessed them.

Principle: The courts will usually favour a finding of dispossession over discontinuance.

Application: Use this case to illustrate your point that discontinuance is very difficult to establish.

The claim for possession must be adverse; the claimant’s possession of the property must therefore be without the permission of the property owner.

Case precedent – Trustees of Grantham Christian Fellowship v Scouts Association [2005] EWHC 209

Facts: The scouts had been granted a licence to occupy some land, provided they kept it tidy. The scouts used the land for scouting activities between 1959 and 2002. In 2002, the group claimed ownership of the land by adverse possession. Held: As the licence had never been revoked or expired, the scouts’ presence on the land had always been with the permission of the landowner. There could be no claim in adverse possession.

Principle: The squatter’s possession of the property must be without the permission of the property owner.

Application: Use this case to support your argument that possession with permission cannot be adverse.

Case precedent – BP Properties v Buckler [1987] 2 EGLR 168

Facts: Despite the landowners, BP Properties, having legally obtained an eviction order against Mrs Buckler, who lived in the property with her son, she had refused to leave the property. However, Mrs Buckler was disabled and the case had attracted a lot of unwelcome publicity against BP. The company therefore decided to offer Mrs Buckler a licence to occupy the property rent-free in an order to stem the public outcry at their attempts to evict the disabled woman. Mrs Buckler had never formally accepted the offer of a licence but had continued to live in the property until her death. When her son then claimed possessory title to the property on the grounds of adverse possession, however, the court found that there had been a licence granted to Mrs Buckler to occupy the property and that there was therefore no adverse possession claim to be made.

Principle: Where a licence is offered but never refused this may be taken to mean that the licence has been granted.

Application: This case illustrates how the court has in the past used the issue of permission to deny an adverse possession claim.

The finding in BP Properties v Buckler has been criticised because it suggests that a landowner may defeat an adverse possession claim simply by unilaterally granting a licence to the occupier. In his judgment in the case Dillon LJ said that the occupier should have rejected the offer in writing to prevent it from being granted. However, findings in later cases, including Long v Tower Hamlets London BC [1996] 3 WLR 317, suggest that this was a singular case distinguished by its facts and that the courts may in future reject any such line of attack put forward by dispossessed landowners.

For a more in-depth critique of this case and its implications see Herbert Wallace, ‘Limitation, prescription and unsolicited permission’, Conv. 1994, May/Jun, 196–210.

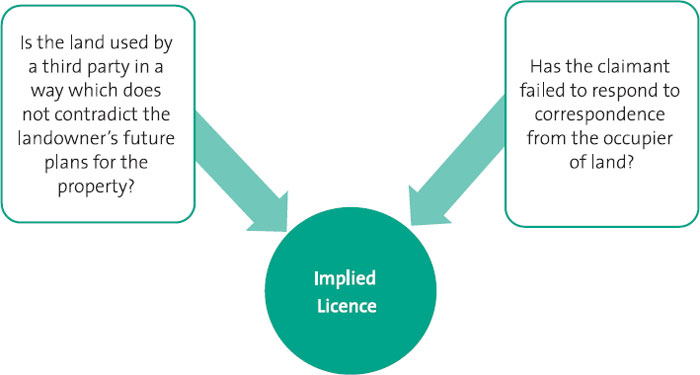

Implied licences

In Wallis’s Cayton Bay Holiday Camp Ltd v Shell-Mex and BP Ltd [1974] Lord Denning argued that the claimant’s occupation of the property was by virtue of an implied licence from the owner, and therefore there was no claim of adverse possession to answer.

Case precedent – Wallis’s Cayton Bay Holiday Camp Ltd v Shell-Mex and BP Ltd [1974] 3 WLR 387

Facts: The case concerned land adjacent to a petrol station. The land belonged to the petrol company but was not fenced off from the farmland surrounding it. The petrol company had initially planned to use the land for development, but the development had never taken place. After some years the farm was sold and the new owners of the farm proceeded to use the petrol company’s land for grazing their cattle, incorporating it into their own field. This continued for 11 years until the petrol company wrote to the farmer offering to sell the piece of land to him. The farmer did not respond to their letters, but continued to use the land. When the petrol company subsequently took steps to fence off the land, the farmer claimed ownership of it by adverse possession. Held: The farmer’s claim failed on the basis that his use of the land was under implied licence from the landowner.

Principle: Use of land in a way which does not contradict the landowner’s intended future use of the property will amount to an implied licence on the part of the landowner.

Application: Use the facts of this case to illustrate the circumstances under which an implied licence will be found in adverse possession claims.

He also suggested that, in this particular case, the failure of the claimant to respond to the landowner’s correspondence amounted to wrong-doing sufficient for the claimant to be estopped from claiming possessory title to the property in any event.

The issue was later specifically addressed s 4 Limitation Amendment Act 1980, which stated that it should not be assumed that a claimant’s occupation of land is by implied permission of the landowner merely by virtue of the fact that his occupation is not inconsistent with the latter’s present or future enjoyment it. The case of Buckinghamshire County Council v Moran [1991] 3 WLR 152 has subsequently confirmed that the doctrine of implied licence is negated by the new legislation.

The Limitation Act 1980 is nevertheless clear in stating that this will not prevent a licence from being implied where the facts of the case support this (s 4).

Possession

In order to show adverse possession the claimant must be in actual possession of the land. In Powell v MacFarlane Slade J defines this as asserting: ‘an appropriate degree of physical control’ over the property.

Case precedent – FowleyMarine (Emsworth) Ltd v Gafford [1968] 2 WLR 842

Facts: The claimants owned a tidal creek, which they managed and charged mooring fees for boats wishing to use it. Held: Their management of the land, coupled with their policing of it and the charging of a mooring fee were ‘as sufficient as the location in question would permit’ in terms of evidencing their possession of it (per Wilmer LJ).

Principle: What constitutes possession in an adverse possession claim is a matter of fact and degree.

Application: Use this case to illustrate a situation in which actions other than fencing off the land will nevertheless constitute possession of it for the purpose of making a claim in adverse possession.

Case precedent – Tecbild Ltd v Chamberlain (1969) 20 P&CR 633

Facts: The claimant lived next to land owned by developers. She claimed ownership of the land by virtue of adverse possession, on the grounds that her children played on the land as and when they had wished and that the family ponies had been tethered and exercised there (although they had been stabled elsewhere). Held: The claim failed. The claimant’s use of the land was not sufficient to constitute possession.

Principle: In order to show adverse possession the claimant must assert ‘an appropriate degree of physical control’ over the property.

Application: Compare this case against the facts in your own scenario to decide whether an appropriate degree of physical control has been asserted.

Intention to possess

The claimant must have the intention to possess the property, or ‘animus possidendi’.

Facts: A woman sought to claim the right to live in a disused quarry on grounds of adverse possession. However, as she had previously written to the council offering to pay rates and rent for the land on which she was living, and even stated that she would be prepared to buy a corner of the quarry on which to live, she could not be said to have had the required intention to possess the property adversely.

Principle: The claimant must intend to possess the property adversely.

Application: Use this case to support your claim that the claimant must intend to be in adverse possession of the property in question.

It is irrelevant whether the squatter’s intention to possess came in the mistaken belief that they already owned the property in question (Pulleyn v Hall Aggregates (Thames Valley) ltd (1992) 65 P&CR 276; Fowley Marine (Emsworth) Ltd v Gafford).

Understanding: making a claim in adverse possession

The rules relating to the making of a claim in adverse possession depend upon when the adverse possession took place and whether the land in question is registered or unregistered: