Suffer the Little Children

3

Suffer the Little Children

The Adelaide Advertiser, 7 July 1994

A row over the building of the Hindmarsh Island bridge has erupted between the Premier, Mr [Dean] Brown, and the woman he named Aboriginal of the Year this week.

Ms Doreen Kartinyeri said Mr Brown’s warning against federal intervention in the bridge issue on Tuesday was a ‘kick in the guts’ for those who were trying to protect important traditional areas near the proposed bridge site.

On Monday, the Premier praised and rewarded the work of Ms Kartinyeri, a South Australian Museum historian, who was the main contributor to a report on the significance of the site compiled for the federal Aboriginal Affairs Minister, Mr Tickner… The following day [Mr Brown] told Mr Tickner to ‘stay out of South Australia’ and allow the bridge to go ahead. Last month, Mr Tickner extended a 30-day emergency ban on the construction of the $1.5 million bridge, saying the building site could be land with great Aboriginal heritage.

Mr Brown said the Aboriginal heritage issues surrounding the bridge had already been addressed under the State’s Aboriginal Heritage Act.

However, Ms Kartinyeri said the issue had been ‘far from adequately addressed’ and that Mr Brown had dismissed the Aboriginal heritage values of the area.

Ms Kartinyeri, who has ancestoral [sic] links with the area, said construction of the bridge at its proposed location would destroy a sacred women’s site of great importance to the Ngarrindjeri people.

‘The Government is looking at dollar signs. I am looking at what we’ve got left to offer future generations,’ she said.

Ms Kartinyeri said she hoped Mr Tickner would put an end to the bridge. ‘If he has any decency and respect for the Aboriginal people of Australia he will not take any notice of what Dean Brown has to say,’ she said.

I was furious.

Kundjawara [great-great-grandfather Benjamin Sumner’s first wife] and Malpurini [great-great-grandmother, Benjamin Sumner’s second wife] are buried down on Kumarangk. That is my people’s home and that was something that the old people loved. My ancestors are buried there. How would whitefellas like it if Aboriginal people dug up their great-grandmothers? My teaching since I was a little girl has always been about my people from Kumarangk and Raukkan. From oral histories passed down I heard about how in the old days the whitefellas had raped our women and then they had raped our land. And now in the 1990s they were going to do it again. How can they put a fucking great big bridge into that earth, when my Aunty Rosie wasn’t even allowed to disturb it with her walking stick? Those waters and that island are sacred to us and it’s my responsibility to take care of them. It always has been and I can never let go of that, no matter what a big burden that can be.

As usual, the authorities and the Aboriginal Heritage Act were not going to help. As soon as I heard they were planning to build a bridge from Goolwa to Hindmarsh Island, I went to Parliament House to talk to the South Australian Minister for the Status of Women, Barbara Weise. Swearing her to secrecy, I shared some of the women’s knowledge. I even demonstrated some women’s body positions to try and help her understand how important it was. I just wanted her to state in Parliament that she had seen me and been told about the women’s knowledge and that she believed I was telling the truth, but no, she wouldn’t do anything to help stop the bridge.

I had already been to see David Rathman [Chief Executive of the Department of State Aboriginal Affairs], but he said he couldn’t do anything either. Later I found out that Sarah Milera, another Ngarrindjeri woman with knowledge, had also been to see David and had got the same response. All he would do was quote Section 23 of the South Australian Aboriginal Heritage Act 1988 to me, that the Minister for Aboriginal Affairs had the final say. The Minister was, of course, a whitefella and the government was standing to lose a lot of money if it didn’t go ahead with its agreement to build the bridge, so yet again Aboriginal heritage was going to suffer.

I would have thought that since both Sarah and I raised the issue with David, that would have been enough for them to have an investigation into what we were saying. They could have done that quite easily. We could have called Auntie May Wilson, Veronica Brodie, Aunty Gracie Sumner, Aunty Sheila Goldsmith and Aunty Connie Roberts. Some of the older ones were still alive then.

I sat at my desk in my office at the South Australian Museum and stared at the blank piece of paper in front of me. I’ve always had a good sense of what to do next. If they weren’t going to protect this area under South Australian laws, I would just have to go further up. I would have to write a letter to the Federal Minister for Aboriginal Affairs, Robert Tickner. I had to do my duty for my people and my culture.

I knew what I wanted to say. That’s another thing I’ve always had. Just let anyone try and put words in my mouth. I never got much education in the white way and I won’t take anyone using big words around me. I often say to people, ‘Don’t use them big jawbreakers. I don’t know what they mean. Tell me what you’re saying in words I can understand.’ Same with writing a formal letter. It’s hard for me to put it in the right way, so often I will get someone I trust to help me. Steve Hemming would help me. I rang downstairs for Steve. Good, he was there. I went down to see him.

Steve was in the tearoom. The Museum archivist Kate Alport was there, and so was Deanne Hanchant, who was working in repatriation, taking back to their communities the Aboriginal skeletons the Museum had held and used for scientific tests over hundreds of years. The Director’s secretary was popping in and out. At the time Philip Clarke was Registrar and Steve was Curator of Anthropology and Project Manager for the Aboriginal Family History Unit I was running. They weren’t talking at the time because there was some aggro between them.

I told Steve I was upset about them wanting to build a bridge from Goolwa to Kumarangk because I knew how significant that area was, especially to Ngarrindjeri women. I told him about how Aunty Rosie had passed on her knowledge to me. I also told him about Aunty Laura Kartinyeri yarning to me. That’s when Steve found out about what was to become known as the Ngarrindjeri ‘women’s business’. Because he was a man I never told him any details and he never asked, but Steve understood how important this was for me, so I asked him if he would type up a letter for me to Robert Tickner asking him to stop the bridge, and he agreed. We went upstairs to my office.

I showed Steve the notes I had made about what I wanted to say to Robert Tickner and then I told him to type it up as it was. Steve went to his office and typed the letter up. Then he came back and showed it to me. He had changed one of the sentences a bit, so I gave him a piece of my mind. He said he had just tidied up the grammar, but I didn’t like my words being mixed around. I told him to go back and retype it. When he’d done that he left it with the secretary to fax it through to Robert Tickner’s office, and told the Museum Director Chris Anderson about the letter straight away.

Before this I never was into Aboriginal politics. All I knew was I had to vote on election day and that was it. I was too busy to think about anything else while I was raising my children and foster children, although I had a lot of admiration for the work Aunty Gladdie Elphick1 was doing during the Don Dunstan era [Labor Premier 1967, 1970–9]. I had a lot of connections with Aunty Gladdie in the 1960s and saw first-hand the way she was working, but this was all local work, all in South Australia. I had heard about Eddie Mabo,2 but not much else. In 1992 I saw a newsflash on TV and I said to myself, ‘Good luck brother, may you win’. Then when the decision came down, I cried, I was so happy. I never would have guessed at the time that I would be involved in a similar struggle that would work very differently for me. But then I didn’t understand the way white politics worked.

I remember the first time I ever got involved in Aboriginal politics was after the Native Title Act had been passed in 1993 and a meeting was held at the Aboriginal Legal Rights Movement. I went along and stood up and said I supported native title and any way of Aboriginal people keeping their land. I didn’t understand the legal system or bureaucracy, but at least I’d had my say. But that was it. I never knew anything about Keating’s Redfern speech, or the Howard government’s Ten Point Plan and its proposed Wik legislation,3 even though those things came later. In fact I only ever learnt a little tiny bit about those things when I got into writing this book and I still don’t understand them properly now.

At the time I was working in the Museum I attended a lot of meetings with anthropologists and people wanting to know about Ngarrindjeri culture. I’d tell them lots of things they wanted to know just to please them. I had worked out by then that the best way to get what I wanted in this world was to give whitefellas what they wanted without letting them know that I wasn’t giving them all of it. When there were things I didn’t want to say, I used to try and put them off. I had to make them know how important Hindmarsh Island is to my culture, without giving it all away.

Writing the letter to Tickner was the first time I had to think politically about the world and what was happening to blackfellas. It made me stand up and speak my mind, and writing that one letter made a significant change in my life. But because I did that I was labelled an ‘activist’ by the media. I still can’t understand how I could be an activist when this was the first time I had ever really stood up for my culture, my own personal precious piece of country.

1945: Fullarton Girls’ Home

I was heartbroken. My life was falling to pieces. I was so confused, hurt and angry. I could hear Nanna’s voice over and over saying, ‘Go in there and be with your sister’. The only sister I had there was Elsie.

Elsie wasn’t able to go home to Raukkan for Christmas that year, because Mummy was no longer there, so it was good to see her, but I felt like I was going wurangi [mad]. I just couldn’t understand what was happening. She took me over to sit down under the mulberry tree in the yard and we were both crying. I said, ‘Nanna told me Doris would be here. Nanna lied to me’. Elsie said, ‘No, Nanna would never lie to you. That’s what they would have told Nanna so that they could get you here,’ and she was right. For years I never considered myself part of the Stolen Generations4 because I had agreed to go into the Home. But I was stolen. They got me there by lying to me and my family.

Elsie was comforting me. I was reflecting on the time when Mum got pregnant and told us she was having another baby. It was so good, we were all so happy. We were looking forward to the baby’s birth and the next thing we knew, Sister McKenzie had put Lila, Thelma and then Elsie into the Home, Mummy died and Doris was gone.

Elsie and I cried together for quite a long time and some of the other girls came down and sat with us. Elsie was feeling it too. She had lost two mothers — her own and then mine.

The anger boils

I think that’s when I started to really get angry. These bloody white bastards were taking control of everybody. We didn’t know what they were doing half the time. It seemed to me like no matter where I turned and who I met in white society, those fellas were aiming guns at me and wanting to bring me down.

I guess I was lucky to know quite a few Aboriginal kids in the Home, like Ruby and Viola Wilson, who’d lost their mother before my mother died, and Shirley Wilson was there, but her mother and father were living, so children weren’t just taken because they’d lost their mother. So okay, I had my cousins there, and Ruby Wilson was one of my best friends on Raukkan, and I should have been content, but I wasn’t, because I had been so excited at the thought of seeing Doris. She would have been going on five months old, and I can’t tell you how devastated I was that she wasn’t there.

And so my time in Fullarton was very unhappy. I was there concentrating on not being there and I never made friends with the white girls in that Home. The others all had white friends, but I refused to mix with them. All I had was my Aboriginal family, the only people I could trust. White people were the enemy.

On my second day at the Home I was taken to Matron’s office again and I was given a little run-down on what was expected of me. As plain as day I remember Matron Watson saying to me, ‘You’re not here as a punishment, you’re here as a privilege’. You could have fooled me! I didn’t understand how the English language worked. The way I understood it if you did something good you got a privilege. I hadn’t done anything good or bad, but it sure felt like I was getting punished, not being privileged.

Then I was sent into the schoolroom. Lower primary school was conducted in a building on the grounds and after Grade 4 the girls went to Parkside Primary. All my relations were saying hello and introducing me to their friends, so it wasn’t until after about an hour that I realised they had put me back into Grade 2. Sister McKenzie must have given Matron all my background, and knowing I had missed the last term after Mummy died, they must have decided to make me repeat the year. They didn’t just put me back to the beginning of Grade 3, but they put me back two whole years. Well that was the last straw. I decided to become what Sister McKenzie said I was, a very naughty girl.

The beginning of rebellion

I deliberately did little things to get into trouble. I wouldn’t do my chores, so they’d lock me in the boiler room. I’d while away the time by playing knucklebones with little pieces of coal, sitting on the floor in the dark. After being put in there about ten times they realised that wasn’t working, so then they put me into scullery. Every week I was in scullery. I had to wash all the dishes from breakfast, lunch and tea. There were bread and butter plates, soup plates, big plates, knives, forks and spoons for about seventy people to wash. Some of the pots that they cooked in were bigger than me, and I put them on the floor, because I couldn’t reach them in the sink, and scrubbed them with a big wire brush. I would only have one other girl to help me, someone else who’d played up. A few times that was a little German girl called Patty Unger. She had been brought down from a migrant camp in Woodside in the Adelaide Hills. She had no brothers or sisters and very few visitors, and some of the bigger white girls used to punch her around. I wonder now whether she got treated badly because of the Second World War.

A visit from Dad

After a few months I had a visit from my father. He was allowed to visit on a weekend, but he had to ask permission first. There was a little room called the Visitors’ Room with a little lounge and a table with a lamp. Some of the bigger girls used to bring drinks in for the visitors. It was on this visit that Dad told me he had found out Doris was in Colebrook Home at Eden Hills. He told me I should stop playing up because we now knew where she was and that he and my cousin Nelson had been up there and seen Doris. He also told me that my cousins Flo, and Dennis and Francis, Ellen Rankine’s sons, were there too.

There were restrictions on family visits. You were only allowed so many visitors per month, and the children were only allowed to write home once a month.5 Dad told me that he had wanted to see me the day he saw Doris, but was not allowed to visit me. Perhaps there was some Salvation Army event on, which also meant visitors weren’t allowed. It was hard, because he had a long way to travel and he couldn’t always afford it.

Dad told me that Doris looked very much like Connie, with short curly hair. That was something Nanna always cried about, whether Doris looked like Connie or like me. I was pleased that at last we knew where Doris was, so I asked Dad when he was taking her home and when he was coming back to get me. He pretended he didn’t hear me. He said he had to go so he wouldn’t miss the train, and got up to leave. I chased him out to the gate. He stepped through the little side gate and headed down the road. June Campbell came after me and wouldn’t let me follow him. I stood there peering through the gate. After a while she opened the gate to let me see that he had gone.

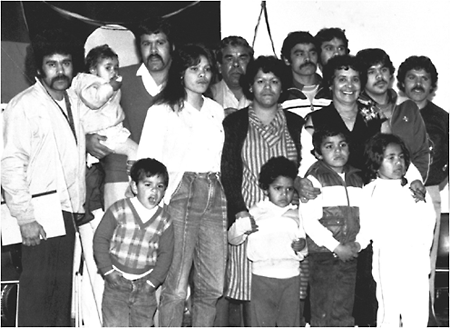

A Raukkan school photo, c. 1943. (L–R) back: teacher, Shirley Wilson, May Sumner and Elsa Sumner; middle: unknown, Hester Rigney and Doreen Kartinyeri; front: Alice Sumner, unknown and Vida Sumner. Photo courtesy Doreen Kartinyeri Archival Collection, Native title Unit, Aboriginal Legal Rights Movement, Adelaide.

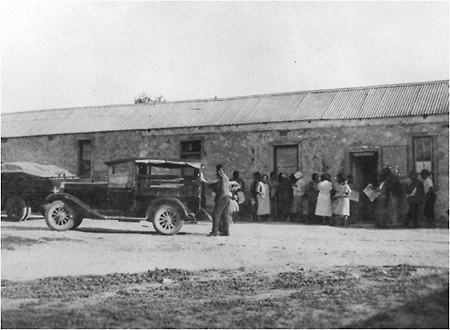

Outside the Raukkan Post Office waiting for the Mail to arrive, c. 1920s. Photo courtesy Doreen Kartinyeri Archival Collection, Native title Unit, Aboriginal Legal Rights Movement, Adelaide.