Why Strict Scrutiny Requires Transparency: The Practical Effects of Bakke, Gratz, and Grutter

Why Strict Scrutiny Requires Transparency

The Practical Effects of Bakke, Gratz, and Grutter1

As the 2002–2003 term of the United States Supreme Court unfolded, few if any of its pending cases received as much media attention as the twin bill of affirmative action cases. In Grutter v. Bollinger and Gratz v. Bollinger, the Court had taken on two distinct challenges to affirmative action policies at the University of Michigan (UM). Barbara Grutter was challenging a racial preference system built into UM’s School of Law, and Jennifer Gratz was challenging the use of racial preferences by UM’s undergraduate admissions. Through the briefing, oral argument, and subsequent Court deliberations, most of the betting ran against the university. Recent Supreme Court decisions had struck down affirmative action plans in employment and contracting; a majority of the justices had records hostile to racial preferences in nearly all contexts. Moreover, most elite colleges and professional schools had been using racial preferences to favor minorities in admissions for over 30 years, and nearly everyone conceded that such programs should not persist indefinitely. On June 27, 2003, the Court announced both decisions. In Gratz v. Bollinger, a 6–3 majority of the Court ruled that UM’s undergraduate admissions system was patently unconstitutional; in Grutter v. Bollinger, the Court held by a slender 5–4 vote that the law school’s system survived constitutional scrutiny, but only subject to a number of constraints and only temporarily. On its face, this seemed like a stinging rebuke to the university’s policies and a considerable narrowing of the scope of affirmative action. Yet the front pages of newspapers across the country the next day showed a gleeful Mary Sue Coleman—the president of the university—literally jumping for joy on news of the decisions. The question must be asked: why was this woman smiling?

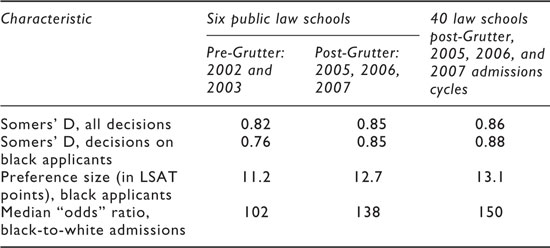

The remarkably simple answer is this: President Coleman knew that, in practice, the Grutter and Gratz decisions would have little effect on the scale and effects of the university’s affirmative action policies. Indeed, as I will discuss in this chapter, Grutter and Gratz—along with their progenitor, Bakke v. University of California—have collectively had effects almost directly opposite to those articulated in the decisions. At least among public law schools in the United States, and at the University of Michigan’s undergraduate college itself, racial preferences became larger, not smaller, after Grutter and Gratz; particular racial classifications became more, not less, determinative of admissions decisions; and for most schools, the entire process—far from doing away with “mechanical” admissions processes—became more mechanical than ever. An era when higher education would embrace race neutrality, which Justice O’Connor (the architect of Grutter) confidently predicted would arrive in the 2020s, now seems further away than ever.

This is unusual: while Supreme Court decisions do not always have the sweeping effects implied by their words (Canon and Johnson 1999; Rosenberg 2008), they do tend to push on-the-ground behavior in the direction laid down by the Court. At worst, one would think, a Court holding would have no effect at all. So producing effects opposite to those pronounced by the Court is a remarkable, if dubious, legacy of Grutter and Gratz, and it makes these cases, along with their legal forebearers, interesting material for a case study in the exercise of judicial authority. Examining the on-the-ground effects of these decisions also helps us think about how the Court can operationalize the idea of strict scrutiny—the standard that, in theory, governs affirmative action law.

A Few Facts About Admissions Preferences

Grutter, Gratz, and Bakke are intrinsically interesting because most readers have experienced the remarkable opacity of college and university admissions. Elite and advanced-degree schools thrive on the allure of selectivity, and like all allurements, this one depends on a certain air of mystery. Listen to any admissions officer’s speech on “how to get in” and you will know exactly what I mean. The mystique of higher education admissions is also quite important in understanding the challenge of judicial regulation. Let us begin, then, with a brief glimpse behind the veil.

Both elite universities and professional schools introduced “pro-minority” racial preferences in the late 1960s, an innovation that capped a very turbulent generation of change in admissions. Before World War II, very few schools in the United States were truly “selective” in the modern sense (Karabel 2005; Lemann 1999). Nearly all schools admitted the bulk of their applicants. A few elite ones had admission exams, and a number of prestigious schools placed various social obstacles in the path of admission.2 Postwar America, however, witnessed an explosive growth in college enrollment,3 and middle-class Americans began to think their smart children could legitimately aspire to attend famous schools and pursue elite professions. The elite schools themselves, faced with unprecedented demand and the rapid emergence of science, technology, and quantitative social science as subjects of intense national interest, were rapidly injecting an ethos of meritocracy into many aspects of their operations, including admissions. The schools embraced standardized tests as a means of reducing “class” prejudice, and embraced the idea that competitive admissions should be based primarily on objective “merit.” To protect the children of alumni and college sports, schools used “legacy” and athletic preferences as well, but meritocratic criteria were dominant by the 1960s, as elite schools found themselves admitting only a third, a quarter, or even a fifth of their applicants.4

Part of the new meritocratic vision embraced greater ethnic and racial diversity, and both elite college campuses and professional schools undoubtedly became more open and welcoming places in the early 1960s. But by the mid-1960s, many colleges realized they would have very small black enrollments without special efforts. Unprecedented levels of college activism, initially focused on the Vietnam War but soon spreading to other issues, also put an intense spotlight on the “racial climate” on campuses and the paucity of black students. Consequently, over a relatively short period between 1967 and 1970, dozens of elite and professional schools adopted special minority admissions programs. These usually involved some special outreach efforts, but always also included “preferential” admissions for blacks (and soon, Hispanic) applicants, meaning that low or middling test scores and grades were discounted.

College administrators initially based racial preference programs on three key premises. First, they believed it was essential for colleges to do their part to foster the development of national minority leadership in politics, in the professions, and in the technocratic elite. Second, they believed that it would take some time, perhaps a generation, for the effects of civil rights programs to kick in and correct the effects of poverty and poor education on black students. Third, they knew colleges would be accused of hypocrisy if they could not generate reasonably significant numbers of minority students, since they obviously had no qualms about using preferences for athletes and (in private colleges, at least) legacies. Under these circumstances, instituting preferences large enough to generate substantial minority enrollments (i.e., very large race preferences) seemed like an obvious step, and one they hoped would rapidly fade as racial gaps in academic preparedness declined.

As a significant number of schools instituted minority preferences, still others felt compelled to follow suit, in part because the preferences of other schools tapped all the readily available minority students who could be admitted on race-neutral grounds. By the mid-1970s, preferences were pervasive at the top 200 undergraduate programs outside the South and in most law and medical schools, and continued to spread in subsequent years.

After several decades of rapid evolution, higher education admissions systems had reached a kind of stasis by the late 1970s. Although there have been some subtle changes since then, almost any important, substantive fact one could adduce about elite and professional-school admissions in 2012 would have held 35 years ago. The irony is that it is this exact era when an array of schools have faced legal challenges, and, in the perception of outsiders at least, universities have had to pass through one gauntlet after another. A question to keep in mind as we proceed is whether the net effect of this legal ferment has been to solidify, rather than disrupt, the ways that universities factor race into admissions.

The essential, continuing elements of racial preferences have been these:

- Racial preferences are driven by gaps in levels of academic preparedness. Ever since college admissions officers started thinking seriously about race in the 1960s, they have realized that the median black applicant has academic credentials (e.g., test scores and grades) dramatically below the median white student. In the mid-1970s, for example, the median black typically had credentials around the 10th percentile of the typical white5). Any specific threshold of credentials established as an academic target (say, presumptively admitting students at the 70th percentile and above) would have the effect, then, of admitting whites at 10 times the rate of blacks. (Smaller but analogous gaps exist between Hispanics and whites.) Nearly all university preference systems are driven by this fundamental conundrum. And all predictions that racial preferences would fade over time have been premised on the belief that these racial credential gaps would themselves largely disappear. But while access has increased dramatically (black college enrollment, for example, increased nearly tenfold from 1968 to 2008 (Statistical Abstract 1981, 2010)), the relative level of minority preparation has improved only modestly (the median black credentials in most higher education application pools is now at about the 15th or 20th percentile of the white distribution). Thus, the absolute number of high-credential blacks and Hispanics has increased sharply over time, but race-neutral methods would still tend to produce results that disproportionately exclude blacks and Hispanics.

- Consequently, racial preferences are not “tie-breakers,” but rather a central factor that transforms the application of the typical affected candidate. Most admissions officers more or less “race-norm” applicants— that is, they consider the academic preparedness of each candidate relative not to the general admissions pool, but relative to the preparedness of other candidates of the same race. This does not necessarily mean that admissions decisions are racially segregated; it does mean that the admissions officer is at least making a mental adjustment of test scores and grades based on the race of the applicant.

- Since the “preparedness gap,” relative to whites, is on average different for Hispanics, blacks, and American Indians, the size of racial preferences are, usually, correspondingly different for each of these groups. Especially where there are large numbers of both Hispanic and black applicants, administrators are careful to calibrate preferences to roughly correspond to the relative size of their applicant pools. For example, suppose that 10% of a school’s applicants were black, and 5% were Hispanic. Using the same size preference for both groups would produce something like a 2:1 ratio of Hispanicto-black admits; since the school wants admissions to be reasonably close to application ratios, race-specific calibration of preferences is adopted.6

- Preferences come with costs, especially for the beneficiaries. In the early days of affirmative action, there was much speculation (and hope) that minority students admitted with large preferences would “catch up” in academic skills and achieve levels of academic distinction comparable to their classmates. Scholars now agree that this happens occasionally, but is not the typical outcome. The median black student admitted with a large preference tends to end up with grades that put her somewhere near the 10th percentile of the GPA distribution (this holds in both colleges and graduate schools), and median Hispanic student (who receives a smaller preference) tends to end up around the 25th percentile of GPA. (Minority students admitted without preferences, in contrast, perform pretty much the same as everyone else.) More controversial is the question of whether the low grades that result from preferences are associated with other problems—less learning, stigma, loss of academic self-confidence, a tendency to switch into less rigorous academic majors, lower graduation or professional certification rates, and worse earnings in the long-term.

Although many of the ideas in point (4) above—often clumped together as the “mismatch hypotheses”—are disputed, there is not much disagreement, especially among admissions officers themselves, that (1) through (3) accurately characterize university preference programs. Indeed, over the years enough data about admissions systems has leaked out that these basic features can hardly be denied.

The Structure of Preferences

The Supreme Court’s first substantive decision on university preferences came in Bakke. The University of California at Davis School of Medicine had an unusually rigid preference system; the school set aside 16 out of 100 spots in its medical school for minority applicants. This was a true “quota” system. Since “quota” is such a lightning-rod term in affirmative action discourse, it is worth discussing its meaning in some detail, and distinguishing it from other preference systems. Indeed, since the Supreme Court’s efforts to regulate affirmative action have often been suffused with ambiguity, some conceptual and terminological precision now will pay large dividends when we examine the Court’s decisions.

Consider two similar schools that each enroll 100 new students every fall. School A has a rigid quota of 16 minority spots, while School B has a flexible “goal” of enrolling 16 minorities per year, on average, over many years. The rigid quota puts School A at two disadvantages. First, if the pool of minority applicants is particularly thin in some years, School A must admit some particularly weak applicants to meet its annual quota. School B, in contrast, can admit extra minorities in years with strong applicant pools, and fewer minorities in lean years, thus maximizing the quality of its minority students over time. Second, School A must make admissions in waves, since it cannot predict its yield rate exactly (especially with a group as small as its minority quota). It will admit some students in April, see how it fares in yield, and then admit additional students off its wait-list over the summer. These students will tend to be significantly weaker, since the strongest wait-list students will probably have accepted offers from other schools to nail down their plans. School B does not need to play this inefficient game. It can admit its strongest minority candidates based on average yield rates over time; if in the end it falls short this year, it will make it up next year or the year after.

Thus, regardless of how one feels about preference policies, quotas are not very good ways to implement them because of their rigidity. They are likely to exist only if a school’s administration is so bureaucratic, or so dysfunctional, that policy-makers cannot trust policy implementers to pursue a flexible goal in good faith over a period of time. A quota guarantees results at the cost of efficient implementation.

From a legal standpoint, quotas are particularly troublesome. They imply a spoils system, in which politicians or administrators simply carve up state benefits into racial “shares.” They also make explicit a process in which applicants of different races are not directly compared with one another. Under the Davis quota, it didn’t matter whether there were 100, or 5,000, white applicants with stronger credentials than the 16th enrolled minority.

Consider, by way of contrast, a “point” system. Suppose that School B considers a combination of factors in admitting students: SAT scores, high school grades, work experience, community service, letters of reference, leadership qualities, and so on. Suppose that it awards points depending on the level of achievement in each of these areas, and admits students who pass some threshold of total points—say, 800 points out of 1,000 possible. Finally, suppose that under this system, only an average of 5% of the admitted students are minorities, but that if School B adds 100 points to each minority student’s file, then an average of 16% of its admitted students are minorities.7 To achieve the racial diversity it seeks, School B adopts this point system.

Even though the two systems produce identical results over the long term, School B’s “point system” has several advantages over School A’s quota. The point system will produce rising and falling numbers of minority students from year to year as the strength of the minority pool fluctuates. There is no chance under the point system that the school will be forced to admit an extraordinarily weak minority applicant just to meet the quota; every admitted minority must have at least 700 points on the “non-racial” admissions criteria. Moreover, under the point system majority and minority students are not completely isolated from competition with one another; if the majority pool gets stronger, so that the school raises its admissions threshold to 820 from 800, then minority students will now have to meet a higher (720) threshold as well. Very importantly, the point system is transparent—at least to those administering it. In this design, admissions officers understand how race trades off with other factors, and it is easy to predict such things as the SAT credential gap between admitted majority and minority students.

Now consider a third system, which uses neither points nor quotas, but rather relies on an admissions officer to read the files of all the applicants, to make mental note of all the relevant factors in admission and all the characteristics of all the applicants, and to decide who should be admitted. Such a system used to be called “discretionary” (i.e., based on the discretion of the admitting officer) but has now come to be known as “holistic.” Although a holistic system sounds quite different from a point system, the difference is more apparent than real. If professors are evaluating a few candidates for a new faculty position, or a department chair is comparing a handful of applicants for a graduate fellowship, it is possible to think of the selection as “holistic,” in the sense that dozens of individual characteristics are weighed and compared in an overall, largely intuitive judgment. But when a college or professional school is considering thousands of applicants for hundreds of spots, the process is necessarily algorithmic—the admissions officer or officers have some methodology for weighing the various elements of a file against one another. The only question is whether the algorithm is applied systematically (with an explicit formula) or capriciously. An internally inconsistent system wouldn’t serve anybody’s interests, so no matter whether a school considers its decisions to be formulaic or not they almost certainly are. Given enough time and patience, an investigator could reconstruct the implicit algorithm used by an admissions officer, even one who thinks her admissions decisions are purely intuitive.8

Of course, even in a point system, not every element is objective; determining the strength of a candidate’s writing or the quality of a recommendation ordinarily involves both objective and subjective assessments. The distinction between a “point system” and a “holistic” approach is not really about whether “objective” elements of an application, like test scores, are given more weight, but whether the various elements of applications are compared consistently.

This extended discussion of admissions methods may seem tedious, but as we shall see, it goes to the heart of Supreme Court jurisprudence on affirmative action in higher education.

Bakke v. University of California at Davis

Lawsuits challenging racial preferences in college and university admissions are difficult to bring. Few students know much about how preferences or college admissions work; even fewer know whether they were in the ideal “zone,” where they can show they would have been admitted to a school “but for” the school’s use of racial preferences.9 Still fewer want to put their education on hold while pursuing expensive, complex, and difficult litigation.10 Given the relative handful of challenges that have been brought, a remarkable number of them have turned into major cases.

The first pivotal case was brought by Allan Bakke, a young engineer and Marine veteran who wanted to become a doctor. His challenge to the University of California, Davis Medical School had all the right ingredients: Bakke was a strong candidate; he did not enter another medical school after starting his suit, and, as mentioned above, Davis used an explicit set-aside, or quota, for minorities in selecting medical students. The issue deeply divided a Court which was, on the whole, more liberal than the present Court. Justices Brennan, White, Marshall, and Blackmun held that racial preferences to correct general societal discrimination should be permitted, temporarily, in higher education. Justices Stevens, Stewart, Burger, and Rehnquist held that any consideration of race violated Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. The ninth Justice, Lewis Powell, wrote the deciding opinion, siding with the conservative camp to find the University of California’s racial quota illegal, but siding with the liberal camp to hold that universities were not completely precluded from considering race in admissions decisions. Race, he found, could be used as one of many factors taken into account by a university in pursuit of its legitimate desire to create a diverse student body: