The Method of a Truly Normative Legal Science

CHAPTER CONTAINS an argument to the effect that the proper method for legal science depends on what one takes to be the nature of science, the nature of the law and the kind of questions that are addressed in legal science. It starts from three assumptions, namely that

(a) science is the collaborative pursuit of knowledge;

(b) the law consists of those norms which ought to be enforced by collective means; and

(c) the proper standard to determine what ought to be done is what maximises the long-term happiness of all sentient beings (the H-standard).

On the basis of these assumptions the following positions are argued:

- Legal science, in the sense of a description of the law, is not impossible for the reason that it is a normative science.

- In abstract the method of all sciences, including legal science, is to create a coherent set of positions that encompasses ‘everything’, and therefore also beliefs about the law.

- The proper method for a normative legal science consists primarily of the methods of sociology, psychology and economics, because the ultimate question to be answered is the collective enforcement of which norms satisfies the H-standard. The more traditional hermeneutic methods only play a role to the extent that they establish positive law that contributes to happiness by providing legal certainty.

I. PRELIMINARIES

A. The Nature of Science

If we want to know what the proper method for legal science is, we should at least have some idea of what we mean by ‘science’.1 Science has to do with the pursuit and accumulation of knowledge.2 Moreover, it aims to systematise this knowledge. How this systematisation takes shape depends on the object of the knowledge. In the case of historical sciences, the system derives from the way in which facts and events explain each other. In the case of physical sciences, the system consists in the laws that are formulated and that are used to explain and predict events and facts, and in the way in which laws are derived from each other. In mathematics, the system consists in the axiomatisation of a subdomain and in the derivation of theorems from these axioms.

A third characteristic of science, which explains other important characteristics, is that science is a social phenomenon. It is impossible to be the only scientist in a field, at least in the long run. Science is a cooperative enterprise aimed at the acquisition, accumulation and systematisation of knowledge. The advantage of science over individual acquisition of knowledge is that scientists can build on the results of their colleagues. To quote Newton: ‘If I have seen further it is only by standing on the shoulders of giants.’3

B. Science and Method

A second precondition for the possibility of cooperative knowledge pursuit is that there exists, at least to a large extent, agreement on what count as good reasons for adopting or rejecting a potential piece of knowledge.5 Here is where method comes into the picture. For what is a scientific method?

In one sense of the word, it is a way of going about doing science. It is a kind of procedure that is to be followed if the results are to count as ‘scientific’.6 An example of such a procedure would be the empirical cycle as described by De Groot7 or the Herculean method described by Dworkin in the chapter ‘Hard Cases’ from Taking Rights Seriously.8

In another sense, a scientific method indicates what count as good reasons for adopting or rejecting a potential piece of knowledge. Take, for instance, the mathematical thesis known as the Goldbach conjecture,9 that all even numbers bigger than two can be written as the sum of two prime numbers. One mathematician would count on proof to establish the truth of this thesis, while another mathematician would take a large collection of random even numbers, check whether they can be written as the sum of two primes, and decide from that sample that the conjecture is almost certainly true. If they consider their own method as the only legitimate one, these two mathematicians cannot cooperate in the pursuit of knowledge on number theory.

Reasons in general, and therefore also reasons for accepting or rejecting a particular piece of potential knowledge, are facts that are relevant for what they are reasons for or against.11 The adoption of a method is a choice for what counts as relevant. It is also a choice concerning the kind of data that must be collected in order to argue for or against a potential piece of knowledge. For instance, on a hermeneutic method for legal science, the relevant data for a particular legal conclusion might be that this conclusion is supported by the literal interpretation of a statute, which is adopted as an authoritative text. Therefore, a legal researcher should consult this text, and apply, possibly amongst others, a literal interpretation to it.12

The proper way of going about legal research method in the first sense is, to a large extent,13 determined by method in the second sense of the recognition of particular kinds of data as relevant for the issue at stake. It is this second sense of ‘method’ that will be at stake in the rest of this chapter. Science in the sense of collaborative knowledge acquisition is practically impossible without such a method.

C. Method and the Object of Knowledge

The idea of a method is often connected to disciplines such as law, physics, mathematics, biology, medicine, history, sociology or psychology. In the following I will continue to write about the methods of a discipline, but this is, in a strict sense, incorrect. Which facts count as reasons for or against a conclusion depends on the type of conclusion and therefore on the research question at issue. One discipline may deal with several kinds of research questions and then different methods are relevant in answering these questions. Legal science is a case in point. The question as to what the criminal law of a jurisdiction is – the traditional doctrinal question – differs, for instance, from the question how the contents of the criminal law developed in the course of time – the legal historical question. It is improbable that the same kinds of facts would be relevant to answer these two questions. So, if within a discipline different kinds of research questions are being asked, the issue of method should be focused on a type of research question, rather than on the discipline as a whole.14 For the following discussion of the method of legal science, I will focus on the description of the (contents of the) law of a particular jurisdiction at a particular place and time.15

The point of this example is that scientific disciplines tend to assume that there is truth to be had and also that the methods they employ are normally suitable to discover this truth. Formal logicians assume that proofs lead to true theorems; theorists of the physical sciences assume that the cycle of hypothesis formulation, empirical testing of hypotheses, and improving the hypotheses on the basis of the test results, leads to ever better (in the sense of more true) theories,17 and moral philosophers assume that mutual adaption of concrete moral intuitions and general moral principles lead to ever better moral theories.18

A discipline and its methods are part of a wider body of (hypothetical) knowledge, which includes views on the nature of the discipline’s knowledge objects and theories on how and why particular data are relevant to establish knowledge about such objects. In connection with the proper method of legal science, this would mean that the view concerning this method hangs together with a view on the nature of the law, and a view on which data are relevant to determine the truth – if there is any to be had – of potential pieces of legal knowledge.

At this point I want to mention the possibility that legal ‘science’ does not aim at the pursuit of knowledge about something at all. Many lawyers are involved in keeping the law of a particular jurisdiction in good shape. This is done by describing the law as it is, incorporating recent changes caused by, for instance, new legislation and case law, into the body of legal knowledge, by evaluating the existing law and by proposing changes to it, or even – if one is in the position to do so – by bringing about the desired changes.19 This is an important task of legal ‘science’, and it is benefited by an academic level of dealing with the law, but it is not science in the sense of the word used here of cooperative knowledge acquisition. It is rather a form of highly qualified maintenance of the legal system. There may be some overlap in method with ‘real’ legal science, but maintenance of the legal system is a different discipline from legal science and I will not deal with it here.

D. Three Views on the Nature of Law

i. Purely Procedural Law

It is possible to distinguish at least three fundamentally different views on the nature of the law. One view is that questions about the contents of the law, even ‘easy’ questions, have no true answers and that the law consists merely of a set of acceptable argument forms, such as an appeal to legislation, to case law, to legal principles, human rights, legal doctrine, and the standard canons for legal interpretation and legal reasoning. Legal argument is not aimed at finding the contents of the law, because there is no such a thing. It is aimed at convincing one’s auditorium of a particular legal position. Some arguments are more authoritative than others22 and should therefore be more convincing, but what counts in the end is not whether the correct position was defended – because the correct position does not exist – but which argument was most convincing in the sense of being effective. The law would be, to use Rawls’ phrase, purely procedural,23 with the not unimportant clause that the procedures that constitute the law, the acceptable argument forms and the materials to which they refer – legislation, treaties, case law and custom – to a large extent constrain the possible outcomes.24 The law for a concrete case, or for a case type, would be the outcome of a battle of arguments.25

ii. Law as Social Fact

A second view of the law holds that the law exists as a matter of social fact, independent of what individuals may believe about it, but dependent on what sufficiently many sufficiently important members of a social group think about the contents of the law and think about what others think about it.28 A special variant of this view is that of law as institutional fact, according to which most of the law exists thanks to rules that specify what counts as law.29

This view of law as social fact has two advantages. First, it explains why the law appears to be a matter of fact, independent of what individual persons think of it, and that the contents of law depend on a particular jurisdiction. Second, it explains why lawyers tend to argue about the law as if it already exists and as if two conflicting legal positions cannot both be true.

iii. The Normative View of the Law

The third view of the law assumes that something else is the case. According to this view, the law is essentially an answer to the question what to do, and more in particular what to do by means of rules31 which should be enforced collectively, usually by means of state organs.32 Notice that according to this third view, the law is, not what is actually enforced collectively, but what ought to be enforced collectively. To state it in an overly simplified way: the law is an ought, not an is.33 Therefore, I will call this the normative view of the law. On this normative view there is principally no difference between the law as it is, and the law as it should be.34 Moreover, the law would be a branch of morality, if morality is taken as that set of standards that indicate what would be good and right things to do all things considered and taking the interests of all human (sentient) beings into account.35

Moreover – and this has immediate implications for the method of legal science – the positive law is only ‘real’ law to the extent that it contributes to the recognisability of law and to legal certainty. This means that if the ‘positive’ law can only be established by means of some contestable interpretation, it cannot fulfil its coordinating function anymore and loses its presumptive force as law.

II. THE POSSIBILITY OF A NORMATIVE SCIENCE

In this contribution I intend to outline a method for legal science as a description of existing law,38 on the assumption that the normative view of the law is correct. Legal science would then be a normative science, aiming at the collective pursuit and systematisation of normative knowledge, in particular knowledge which rules should (here and now) be enforced collectively.

This view of legal science has some similarities with, but should nevertheless be distinguished from the view, promoted by Smits, that legal science is normative in the sense that it deals with the question of what the law should be.39 Although Smits is not very explicit about the nature of the law,40 it seems that he considers the law to be a set of rules, etc that exist in social practice. Legal science should, according to Smits, indicate what this practice should be. In my opinion, the ‘real’ law, as distinguished from the merely positive law, is itself an answer to a normative question and legal science as description of this ‘real’ law aims at providing this answer. Despite this difference, the view of Smits on the nature of legal science has an important similarity to my view, because we both assume that legal science deals by and large with the question which rules we should have, or should enforce by collective means.

A. Why Normative Science Seems Problematic

It is a popular view that normative science is not well possible.43 The reason is generally some form of non-cognitivism concerning normative (and evaluative) issues. It is customary to distinguish between the realms of is and ought and to be an ontological realist with respect of the realm of the is, and to be a non-realist with respect to the ought. With regards to is-matters, there would be a mind-independent reality which is the same for everybody44 and which makes every factual proposition true or false.45 With regard to ought-matters, such a mind-independent reality would be lacking. To state it bluntly: whether we agree about it or not, there would be a true answer to every question of fact, while there is no such true answer concerning normative questions. What ought to be done would not be a matter of facts that are the same for everybody, but a matter of taste, or of choice, which may have a different outcome for different persons, even if they are all fully rational. There is no common ground which can function as a foundation for agreement and where there is no ground for agreement, so runs the argument, there is no room for science.

B. Positions

There are many different things which can be justified, such as beliefs, actions, decisions, verdicts, etc. On first impression one might think that these different objects of justification require different forms of justification, but this impression is only correct to a limited degree.

All forms of justification can be reduced to variants on justification of behaviour (including forbearance). This is obvious for actions, and since decisions and verdicts can be brought under the category of actions (taking a decision, or giving a verdict with this particular content), it should be obvious for decisions and verdicts too. The same counts for using rules.

It is even possible to continue along this line, by treating the justification of the different forms of actions as the justification of accepting ‘that these actions are the ones that should be performed (under the circumstances)’.48 In this way, all forms of justification can be treated as the justification of accepting ‘something’. As a catch-all term for things that can be mentally accepted, I will from now on use the word ‘position’.

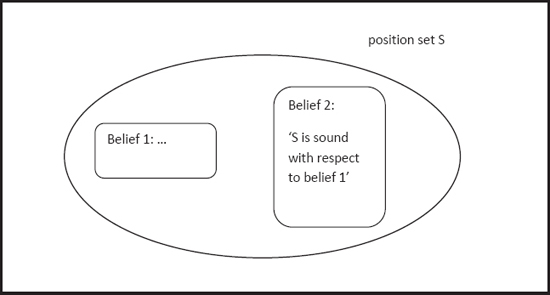

Building on this definition, I will use the expression ‘position set’ for the set of all positions accepted by a person.

C. Local and Global Justification

In the literature on legal justification, justification has sometimes been pictured as a deductively valid argument.49 In such an argument the conclusion (what is justified) must be true given the truth of the premises. The idea behind this kind of justification is that the ‘justifiedness’ of the premises is transferred to the conclusion, analogous to the way in which the truth of the premises is transferred to the conclusion in more traditionally conceived deductive arguments.

It seems to me that this picture is mistaken in at least two ways. First, because it suggests that ‘being justified’ is a characteristic of positions that is similar to truth, only somewhat ‘weaker’. Second, because it overlooks the essentially global nature of justification. In a deductively valid argument, the conclusion must be true if the premises are true. This means that the truth of the conclusion is guaranteed by the truth of the premises, and that nothing else is relevant for this truth.50