Shari‘a Courts’ Response to Competition

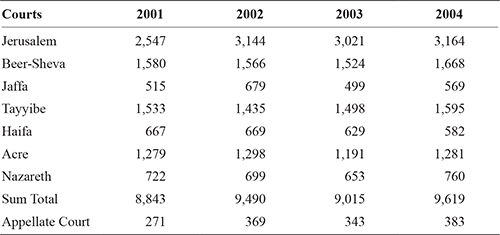

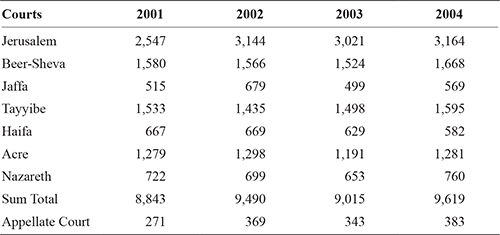

Chapter 10 During the years of parliamentary struggles over the issue of according family courts jurisdiction in personal status matters of Muslims and Christians, opponents of the legislation amendment voiced their grave concern regarding the consequences. They anticipated that the religious courts will be left with no litigants, and that the family courts will not be able to deal with Muslim and Christian litigants in a proper manner. Their main concern was that the civil judges (who are almost exclusively Jewish) will not be able—for lack of knowledge—to apply the material Islamic and Christian laws,1 and that religious values and norms will therefore not be sustained.2 Supporters of the amendment argued in response that the entrance of family courts to this field will only benefit the religious courts, which will have to become more efficient. State officials from the Ministry of Justice (that supported the legislation amendment) have also sought to appease the opponents by pledging that Muslim and Christian judges—versed in religious law—will be appointed to family courts, and that the presiding judges in these courts will be trained in religious law.3 More than a decade after the legislation amendment passed, we still lack a systematic study of its effects.4 Nevertheless, it is to my mind arguable that both its opponents and its supporters were partly right. Supporters of the amendment were right in estimating that the new competition posed by the family courts will drive the religious courts to implement some duly needed reforms. Indeed, as will be shown in this chapter, the fact that the shari‘a courts have no longer a monopoly in the legal “niche” of personal status matters of Muslims has driven qadis to turn their courts into a more “user-friendly” arena. While the opponents’ fear that the religious courts will be drained of litigants has not materialized to date, their skeptic attitude toward the promises that accompanied the legislation seem rather accurate. Despite the fact that the family courts have become accessible to a large constituency of Muslim and Christian Israeli citizens (and permanent residents), no re-organization has taken place in these courts: no training workshops for judges were held; no additional translators to and from Arabic were enlisted; and the number of appointments of Muslim and Christian judges is insignificant.5 As a matter of fact, it appears that the broadening of the family courts’ jurisdiction had no significant impact on their operation, and that they continue to function pretty much as they did before. The family courts’ reaction—or rather, lack of reaction—to the changing situation is of course symptomatic of the indifference that often characterizes Israeli authorities’ treatment of non-Jewish populations. This indifference may provide us, nonetheless, with another clue for understanding Muslim and Christian women litigants’ less than enthusiastic attitudes toward family courts. As mentioned, these courts are seen as rather hostile toward non-Jewish, non-Hebrew-speaking litigants, and their lack of preparedness to cater for the legal needs of that population may indeed drive those litigants away from the family courts. Whereas the family courts did not react in any significant way to the 2001 legislation, the shari‘a courts took quite considerable measures. After investing extensive efforts in thwarting and forestalling the legislation initiative, the qadis must have felt a sense of defeat when the amendment finally passed in the Knesset. Facing a concrete and palpable danger of a personal and institutional “fall from grace,” the qadis had two options: they could decide to compete or not to compete with the family courts which encroached on their jurisdiction. It would have been perfectly understandable if the qadis had decided that they no longer wished to participate in the game after the Knesset passed the legislation amendment. Frustrated with a civil legislation policy that completely ignored their opinion, the qadis could have resigned from their offices in protest,6 or they could have decided completely to ignore the new legislation and to continue doing exactly what they did before. In effect, the qadis’ response was nothing of the sort. Instead of falling into acrimony and resentfulness toward the state, the qadis reacted by taking a wide range of initiatives aimed at internal reform and improvement of the services provided by the shari‘a courts. Irrespective of whether they were motivated by direct personal interest or by a genuine sense of Islamic, nationalist-Palestinian, or communal commitment (or all of these together, of course), the qadis have waged a determined struggle over potential litigants—striving to convince as many litigants as possible that their courts constitute the best place to deal with matrimonial problems. Thus, unlike the family courts, which displayed no interest whatsoever in attracting Muslim litigants into their courtrooms, the qadis went out of their way in order to preserve—and even to increase—the number of files adjudicated in their courts. Why did the qadis react in a competitive manner? Why do they care at all about attracting more litigants—after all, courts are not business firms, and litigants are not customers? Indeed, the motivation behind the qadis’ efforts is probably not economic: their salaries remain the same regardless of the number of cases they handle, and they are not compensated in any way for a greater workload. I argue that the answer to their competitive attitude lies in the realm of legitimacy: from the qadis’ point of view, the more litigants appeal to the shari‘a courts, the more legitimacy the courts—and the qadis presiding in them—have. In contrast, a decrease in the number of appeals might constitute a serious blow to the legitimacy and prestige of the courts and their qadis. As observed by organizational theorists, nonprofit organizations (such as courts of law), much more than business organizations, tend to compete over legitimacy and prestige (see e.g., DiMaggio and Powell 1983, Scott and Meyer 1991: 123, 125). All the more so when an organization suffers from a chronic problem of legitimacy. Bearing in mind the problematic status of Israeli qadis—who are appointed by a non-Islamic regime, to serve in “contaminated courts” (see Chapter 2)—it is easy to understand why it was so important for them not to lose litigants to the family courts.7 This need is even more obvious in Jerusalem, where the Israeli shari‘a court suffers not only from dubious religious prestige (like other Israeli shari‘a courts), but also from a nationalist resentment. In response to the 2001 legislation, the qadis of the Israeli shari‘a courts have preferred, therefore, the active, competitive way of action. Even before November 2001, and surely afterwards, they have gathered for several times, trying to figure out how they can make their courts more appealing to litigants. Three years later, in June 2004, the qadis convened in an emergency meeting in order to discuss a slight decrease in the number of files in Israeli shari‘a courts during 2003 (see Table 10.1). Their main concern was that despite the demographic growth of the Muslim population in Israel, the number of files adjudicated in the shari‘a courts had fallen. In the meeting they also discussed what they called “the bad reputation of the shari‘a courts,” and tried to suggest possible measures that might help to improve the courts’ image.8 Thus, for example, they decided to ease court procedures for issuing declarative judgments and registered deeds (such as marriage and divorce ratifications); they decided that legal councilors and litigants will be allowed to ask for postponements of hearings by fax, instead of having to come to court in person in order to file such a request; and they decided to enforce a stricter dressing code on lawyers and shar‘i advocates (dark trousers, white shirt, dark jacket).9 Table 10.1 Number of Files Opened in Israeli Shari‘a Courts, 2001–2004 Source: based on data from The Shari‘a Courts Administration (http://index.justice.gov.il/Units/BatiDinHashreim/Pages/Report.aspx?WPID=WPQ7&PN=1 [accessed: 10/16/2014]) The institutional responses of the shari‘a courts to the competition posed by the family courts may be divided into two categories: 1. Minor adjustments were introduced into the courts’ administrative procedures and daily routines, with the aim of making the court bureaucracy less burdensome for litigants and councilors. Indeed, in recent years, following the 2001 legislation amendment, the principle of being “user-friendly” has become a major organizing principle in the Israeli shari‘a court in West Jerusalem. 2. Minor legal reforms have been initiated and enacted by the qadis, who made, for this purpose, creative use of their relatively broad judicial agency. As could be expected, most of these legal reforms were designed to improve the status of women litigants in court. There are three possible reasons for the fact that the legal reforms were meant to improve women’s status (and attract women litigants), rather than cater to men’s interests (and attract men). First, we have seen that women, unlike men, have much to gain from appealing to the family court, and it is therefore they who are targeted for persuasion. From a marketing perspective, men may be viewed as “captive clients” of the shari‘a courts, simply because they have no better alternative; women, on the other hand, constitute a much more difficult clientele, since they have an alternative, and presumably, a good one. Thus, in order to prevent the desertion of women in favor of the rival family courts, they are being offered “better bargains,” to convince them to remain loyal to the shari‘a courts. Second, since women are undoubtedly the largest constituency of the court,10 it makes perfect sense to give precedence to their interests, even at the expense of smaller constituencies (that is, men). Third, the current generation of qadis presiding in Israeli shari‘a courts are all graduates of Israeli universities—either of law schools or of social sciences and humanities departments (see Reiter 1997a). Such an educational background may enhance their inclination toward liberal and feminist conceptions of gender equality and drive them to implementing such ideas in their judicial practice (see also Shahar 2004). Let us now explore the procedural and judicial reforms introduced in the Israeli shari‘a courts, and especially in the shari‘a court in West Jerusalem, since 2001. Two of the most burdensome procedures in shari‘a courts have been the practices of identifying the litigants and the witnesses (ta‘rif) and of establishing their personal credibility (ta‘dil; tazkiyya). As a rule, any person appearing before the court must first be identified by two other persons who personally know him/her. In addition, if a person is required to testify, the court must first establish the “good moral standing” (‘adala) of this person,11 by performing a rather complicated procedure (see Tyan 1964: 209a). As one can imagine, such procedures, if strictly enforced, may become truly costly in terms of court time, and it may also put some extra burden on the litigants and their legal representatives, who need to bring such “accrediting agents” to court.12 Thus, being loyal to the principle of “user-friendliness,” the qadi presiding in the Israeli shari‘a court in West Jerusalem decided to nullify these procedures altogether. Instead of identifying litigants and witnesses by the testimony of two acquaintances, identification is presently performed by way of reviewing their ID cards. When opening a case file, the court secretary will usually add a photocopy of the plaintiff’s ID card to the file. Photocopies of the defendant’s ID card and those of witnesses who were summoned to give testimony are added to the file on the day of the hearing. Witnesses are also asked to present their ID cards to the qadi just before they are put under oath,13 but no ta‘dil procedure is enacted. As mentioned in Chapter 7 (see Figures 7.1 and 7.2), about half of the decisions issued by the Israeli shari‘a court in West Jerusalem may be categorized as “declarative judgments” or as registered deeds (mu‘amalat; musadaqat; hujaj). The court staff makes a particular effort to provide such decisions in minimum time (that is, within a single day), but beyond that, the court staff goes out of its way in order to assist litigants in filing these lawsuits. Generally speaking, filing such a petition does not require significant expertise in legal language, nor in court procedures: all it takes is to provide the necessary documents and to testify in front of the qadi to the truthfulness of these documents.14 Nevertheless, many litigants are so insecure that they tend to hire a legal representative even for this evidently simple task. In fact, some lawyers or shar‘i advocates have specialized in “hunting” such litigants just before they enter the court. The lawyers wait in the corridor leading to the court or at the entrance to the building, and approach people who come to court unattended by lawyers. They offer to assist them in filing their petitions, and charge for their services a “modest” fee (usually several hundred NIS).15 In recent years, the court staff has begun to assist litigants in filing such petitions—first by providing them with a detailed list of required documents that they need to supply; and second, by preparing detailed, printed forms for each and every type of petition, to be filled by the litigants.16 When some people still found it difficult to get by, Abu Zayd either directed them to me for assistance, or provided them with a photocopied example of a relevant petition, that they may use as a model for their own deposition. All this, of course, is done in order to assist litigants and to “rescue” them, as Abu Zayd says, from the “vultures’ talons” (that is, from exploitative legal councilors). In recent years, it appears that the ideology of “user-friendliness” has become salient not only in the court’s daily routines, but also in the judicial practices of the qadis.17 The qadis often display a particularly lenient approach in regard to both procedural and material “formalities.” For example, the qadis usually abstain from imposing extra fees on litigants, beyond the fee that they have already paid. Thus, they sometimes insert seemingly irrelevant statements into court rulings, which are meant to exempt litigants from the need to file additional lawsuits. They may add, for instance, to a declarative judgment of divorce (ithbat talaq) a sentence stating that the children are under the custody of the mother/father, or a sentence establishing the financial arrangements agreed upon by the couple (e.g. maintenance payments for the waiting period, payment of the deferred dower, etc.). Qadi Zibdi in particular goes even further than that, and actively corrects statements of claim during hearings, in a manner that better serves the interests of the litigants. For example, he may advise a woman litigant to change the formulation of a lawsuit from “request for approval to rent an apartment” (idhn bi-’isti’jar maskan) to “lodging maintenance” (nafaqat sukna

Shari‘a Courts’ Response to Competition

Outlining Reform Strategies

Identification of Litigants and Witnesses

Facilitative Measures for Registering Deeds

Judicial Pliability