The Cast of Characters

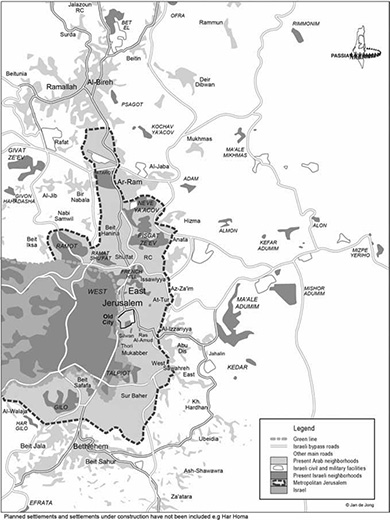

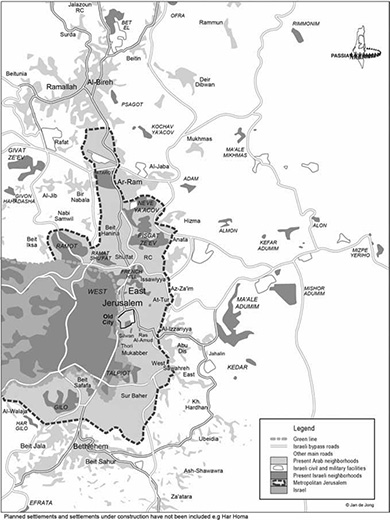

Chapter 6 Whereas the previous chapter has outlined the cultural and political frameworks within which the shari‘a court in West Jerusalem operates, the present chapter aims to provide a detailed description of the various actors that take part in the social interactions unfolding in the court: the clientele of the court (i.e. litigants); the court’s salaried personnel; lawyers and shar‘i advocates; semi-official functionaries appointed by the court (e.g. mediators, marriage registrars). The discussion dwells not only on the sociological and demographical characteristics of each of these groups, but also on the interrelations that they maintain with other actors. It is hard to ascertain the exact number of people who are subject to the jurisdiction of the Israeli shari‘a court in West Jerusalem. From an Israeli official perspective, the court has territorial jurisdiction in matters of personal status of Muslims living in the District of Jerusalem. At the end of 2004,1 the Muslim population residing within the municipal borders of Jerusalem (including the annexed Eastern part) mounted to some 224,800 people (32 percent of the total population in the city).2 In addition, the District of Jerusalem also includes some villages and semi-urban boroughs (e.g. ‘Ain Nequba, Abu Gosh) with a population of several thousands. Thus, we may estimate that officially the shari‘a court in West Jerusalem has territorial jurisdiction over roughly 230,000 Muslims. In effect, however, the Muslim population that may choose to appeal to this court in matters of personal status is considerably larger. As mentioned, in the course of the annexation the borders of Jerusalem were designed on purpose to include as many Jews as possible, and to exclude as many Palestinians as possible from the city (see e.g., Benvenisti 1996: 136–68, Bollens 2000: 65–95). Consequently, several large Arab neighborhoods (e.g. Al-Azariyya, Al-Za‘im, Dahiyyat al-Barid), which undoubtedly constitute part and parcel of the East Jerusalem urban fabric, have been left outside the city’s Israeli municipal borders (see Figure 6.1). The residents of these neighborhoods may appeal to the Israeli shari‘a court on various grounds: they may hold Israeli ID cards, or may wish to obtain such cards; or they may be married to spouses who hold Israeli ID cards. Whatever the reasons, according to my estimation, there are several hundred cases adjudicated in this court each year, which involve litigants from the mentioned neighborhoods or from the other cities or villages in the West Bank (primarily from the vicinity of Jerusalem—e.g. Ramallah, Bethlehem, Jericho, al-Khadr).3 Figure 6.1 Jerusalem Maps—Palestinian and Israeli Neighborhoods in Metropolitan Jerusalem (2000) Source: © The Palestinian Academic Society for the Study of International Affairs (PASSIA). Therefore, in order to calculate more accurately the “pool” of potential litigants who may appeal to the shari‘a court in West Jerusalem, we need to add to the number mentioned above (230,000) approximately 50,000 Muslims residing in the Arab outskirts of Jerusalem, just outside the Israeli-defined municipal borders of the city.4 Moreover, if we consider the Muslim population residing in the greater Jerusalem metropolitan area—that includes large Palestinian urban centers such as Ramallah and Bethlehem (see Bollens 2000: 112)—as potential litigants as well, then the number should rise by approximately 120,000 people. All in all, we may estimate that the pool of potential litigants who may appeal to the Israeli shari‘a court is just a little below 400,000 people. This is indeed a large population, and a highly diversified one. In terms of socio-economic characteristics, the Jerusalem metropolitan area is very variegated: there are some middle-class urban neighborhoods such as Sheikh Jarrah, American Colony, and Beit Hanina; some semi-urban neighborhoods such as ‘Issawiyya, Arab al-Sawahrah, and Jabel al-Mukkabar; refugee camps such as Shu‘afat refugee camp, and large rural habitats occupied by Bedouin tribes (see Figure 6.1). Thus, the population that comes to court is diversified as well: some people have university degrees, others can hardly read and write; some drive fancy cars, others come a long way by foot, since they cannot afford the bus ride; some women wear stylish modern—sometimes even daring—outfits, while others are veiled and covered from head to toe by Jilbabs. Occasional visitors to court—or, in Mark Galanter’s (1974: 97) terms, “one-shotters”—come almost exclusively from East Jerusalem and the larger Jerusalem metropolitan area.5 Most of these litigants hold Israeli, blue ID cards, but a substantial minority among them hold West Bank, orange ID cards. Like the one-shotters, the “repeat players” and the court personnel are mostly residents of East Jerusalem. The notable exceptions are the qadis and the chief secretaries, who are Palestinian-Israelis—that is, they are full-fledged citizens of Israel residing within the 1948 Israeli borders. All the qadis, who have presided in court since 1988, and all the chief secretaries came either from the Muthalath (the “triangle”), an area in Northern Israel, or from Jaffa. The Palestinian-Israeli identity of the high-ranking personnel in the court is of primary significance: it highlights their liminal role as mediators between the Israeli state and the East Jerusalem population. The Palestinian-Israeli population in general is often portrayed as a liminal group with a torn, ambiguous identity: they are both Palestinians and Israelis, and at the same time they are neither “real” Israelis nor “real” Palestinians (see e.g., Shafir and Peled 2002: ch. 4).6 The hybrid, liminal positioning of the West Jerusalem shari‘a court therefore owes much to the liminal identity of its senior staff. The court staff during my years of fieldwork included the following persons—all names are pseudonyms, except for the qadis’ names: Qadi Ziad Taufiq ‘Asliyya, a resident of the Muthalath in Northern Israel, who presided in court between the years 1994–2000.7 He holds a degree in social work, and since 2001, also an M.A. degree from the shari‘a faculty at the University of Hebron. His father, Sheikh Taufiq ‘Asliyya, served as president of the shari‘a court of appeal. Qadi ‘Asliyya is currently retired after another term of qadiship at the shari‘a court in Haifa. Muhammad Rashid Zibdi (Abu Muhammad), the presiding qadi in the years 2001–08. A denizen of Jaffa, who was a former schoolmaster and a school inspector in the Israeli Ministry of Education. He was in his mid-40s, and had no formal education in shari‘a matters. Ibrahim al-Ghol, chief clerk in the years 1997–2000. A graduate of the shari‘a college in Baqa al-Gharbiyya (in Northern Israel). He was transferred to the shari‘a court in Tayybe following a personal conflict with Qadi ‘Asliyya. Muhammad Jamil (Abu Zayd), acting chief clerk.8 A veteran officer in the Jordanian army, about 55 years old, employed in the court since 1995. ‘Izzat Ghandur (Abu ‘Uday), aide to the chief clerk. In his early thirties, employed in the court since 1997. Salih, the “court scribe,” or actually the court computer operator, who is in charge of typing the protocols during the hearings. He is a practical electronic engineer,9 in his mid-twenties, and employed in the court since 2002. Siham—a typist. She is the most veteran employee of the court, working there since 1994. A colorful and somewhat eccentric woman in her mid-thirties. Nadin, a typist, in her mid-twenties, working in the court since 2001. Meir, a Jewish guard. Unlike other guards who served in this position in the past, Meir has become an amicable staff member. His post, nevertheless, is outside the court, in the corridor that leads to the first-instance court, the shari‘a court of appeal, and the administration of the shari‘a courts. Except for the qadis and the chief secretaries, who are senior state employees, all the other staff members are employed by manpower agencies, and therefore do not have tenure. They are dismissed from their jobs and then immediately rehired each and every year by the Ministry of Justice (and until 2001, by the Ministry of Religious Affairs). As a result, their salaries and social benefits are very poor relative to the organized Israeli public sector. At the time Qadi ‘Asliyya was presiding in court, the inequality between state employees (i.e. the qadi and the chief clerk) and employees of manpower agencies caused considerable tensions and grievances among the junior staff. Although the problem was not resolved, the tension seems to have faded away later on. Throughout the years of the research (1998–2000, 2001–05), the division of labor among the court staff was far from constant. Rather, the role-definitions of the various staff members underwent considerable changes. Here are a couple of examples: the function of court courier (mubashir)—a traditional function in shari‘a courts that was also determined by Clauses 17 and 18 of the Ottoman Law of Procedures for shari‘a Courts (1917)—was canceled by the qadi in January 2002. Being in charge of delivering rulings, habeas corpuses and summonses for litigants residing in Jerusalem, the carrier constituted not only a traditional function, but also a crucial one in the court operation. However, this arrangement was terminated, without much ado, by Qadi Zibdi, who discovered, as he told me, that “it simply didn’t work: the courier could not cope with this job; there were piles of summons in drawers, which he didn’t deliver, and hearings were postponed again and again due to deficient notifications.” ‘Izzat Ghandur (Abu ‘Uday) who functioned as courier since 1997 was therefore moved to the position of aide to the chief clerk, and instead of relying on a courier to deliver the documents, the court started to use registered mail.10 This move was naturally accompanied by a new division of labor among the court’s staff. At first, there were some frictions and a sort of turf war between various staff members, but within a couple of weeks, the new aide to the acting chief clerk, assumed full responsibility for maintaining and organizing the court’s small archive: he was the only one, as he never failed to point out to me, that was allowed to enter the archive, to draw and to stow dossiers in it. This organizational transformation—which seems perhaps trivial, but in effect, changed the court’s routines dramatically—was achieved not by orders from above, nor by a premeditated bureaucratic decision, but rather, by a simple organizational adaptation to changing circumstances and needs. In April 2003 a social worker—a Palestinian-Israeli woman from Tayyibe (a Palestinian town at the center of Israel)—was recruited to serve in an “assistance unit” that was established in the court. She started working from 08:00 to 15:00 several days a week in the Jerusalem shari‘a court, only to be transferred to the Jaffa shari‘a court less than a year later (in February 2004). However, during the short period of her work at the Jerusalem court, she functioned more like an additional mechanism of dispute-resolution than a social worker: opponent parties were referred to her by the qadi, and she gained considerable prestige when she managed to reconcile several of them.11 She was allocated a small office niche in the typist’s room, and there she conducted ad hoc dispute-resolution sessions with litigants who agreed to do so. In the short period that she worked in Jerusalem, her presence in court and her methods of intervention certainly changed the entire handling of marital disputes in the court. Similarly, when she was transferred to Jaffa, her sudden disappearance affected again the court’s procedures, which nevertheless did not simply return to what they were before she arrived.12 To my mind, the fact that these two organizational transformations occurred within a period of more or less one year, indicates that the shari‘a court in West Jerusalem constitutes, indeed, a highly dynamic institution—also at the organizational level. Changes and organizational transformations take place quite frequently in this court. Furthermore, it seems that these transformations occur without significant opposition from the court’s staff and its “clients,” who appear to adapt quite easily—and contentedly—to the frequent changes in the court’s routines. As depicted in Chapter 5, it seems that the organizational culture of this court may be described as “prone to change:” an organizational culture that views changes in positive terms, creates very little barriers to change, and handles changes in a seemingly easy-going manner (see Holt et al. 2007). Let us move now to reviewing the other repeat players in the court. They comprise three different groups: lawyers and shar‘i advocates; marriage registrars (al-ma’dhuns); and mediators/arbitrators (ahl al-khayr, muhakamin) appointed by the court. Let us describe these groups one by one. This is the largest and most important group of repeat players. The website of the Israeli shari‘a courts listed some 187 lawyers and shar‘i advocates, who are licensed to work and to represent litigants in the shari‘a courts in Israel.13 This is not a comprehensive list,14 nor does it differentiate between lawyers and shar‘i advocates,15 but it constitutes a good starting point for an attempt to map the various categories of legal councilors working in the shari‘a court in West Jerusalem. Of the 187 lawyers and shar‘i advocates listed by the administration of the shari‘a courts,16 71 are registered as Jerusalemites. Of these, 31 are definitely repeat players, who appeared in court regularly during the six years of my participant observation. Seven others are repeat players but do not live in Jerusalem (five of them are registered in the West Bank, one in Lod, and one in Jaffa). Twelve others are “occasional players” in my terms, which means that they were listed in my field diaries, but less than five times. Of the 38 repeat players, three are women,17 and five, as mentioned, are registered in the West Bank: three (including one woman) in Ramallah, one in Bethlehem, and one in Hebron.18

The Cast of Characters

Litigants

Court Personnel

Lawyers and Shar‘i Advocates