2 – LEGAL FRAMEWORK FOR INTERNATIONAL ARBITRATION AGREEMENTS

This chapter addresses the legal framework applicable to international arbitration agreements. First, the chapter examines the advantages and disadvantages of international arbitration, as compared with other modes of dispute resolution. Second, the chapter considers the various “jurisdictional requirements” of the New York Convention and leading national arbitration statutes (such as the UNCITRAL Model Law), as they apply to international arbitration agreements.1 In particular, the chapter addresses the definitional issue of what constitutes an “arbitration agreement,” an “international” arbitration agreement, a “commercial” relationship, and a “difference” or “dispute,” as well as the New York Convention’s reciprocity requirement.

A. REASONS FOR INTERNATIONAL ARBITRATION

Why is it that parties choose to resolve their international commercial (and other) disputes by “arbitration”? Nations and other political organizations provide courts, administrative tribunals and other forms of dispute resolution, sometimes specialized for commercial disputes. What aspects of the process of “arbitration” induce parties to forego use of these mechanisms of dispute resolution and instead to submit to decisions by international arbitral tribunals?2 The materials excerpted below provide a variety of perspectives, from different historical periods, to these questions.

W. CRUM & G. STEINDORFF, KOPTISCHE RECHTSURKUNDEN AUS DJEME

We fought each other before the most famous comes, dioketes [administrative tribunals] of the castron [district] of Jeme, about the house on Kuelol street…. After much altercation before the dioketes, he made a proposal on which we all agreed: we elected arbitrators from the castron and the dioketes sent them into the house and they made the division.

M. BLOCH, FEUDAL SOCIETY

p. 359 (1961)

The most serious cases could be heard in many different courts exercising parallel jurisdiction. Undoubtedly there were certain rules which, in theory, determined the limits of competence of the various courts; but in spite of them uncertainty persisted. The feudal records that have come down to us abound in charters relating to disputes between rival jurisdictions. Despairing of knowing before which authority to bring their suits, litigants often agreed to set up arbitrators of their own or else, instead of seeking a court judgment, they preferred to come to a private agreement…. Even if one had obtained a favourable decision there was often no other way to get it executed than to come to terms with a recalcitrant opponent.

N.Y. WEEKLY POST-BOY

(May 20, 1751)

[L]et me tell you that after you have expended large Sums of Money, and squander’d away a deal of Time & Attendance on your lawyers, and Preparations for Hearings one Term after another, you will probably be of another Mind, and be glad Seven Years hence to leave it to that Arbitration which you now refuse.

TRANSPARENCY INTERNATIONAL, GLOBAL CORRUPTION BAROMETER 2013

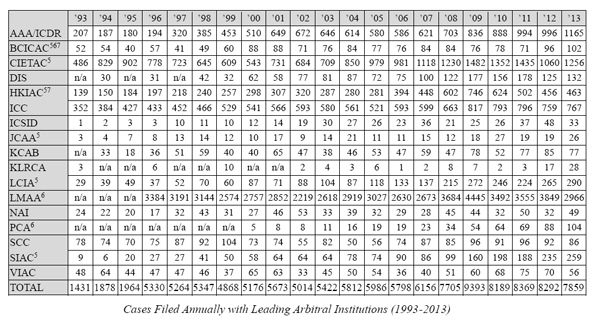

[Transparency International’s Global Corruption Barometer 2013] examines how corruption features in people’s lives around the world. Drawing on the results of a Transparency International survey of more than 114,000 respondents in 107 countries, it addresses people’s direct experiences with bribery and details their views on corruption in the main institutions in their countries.… As the [Report] shows, corruption is seen to be running through the foundations of the democratic and legal process in many countries, affecting public trust in political parties, the judiciary and the police, among other key institutions.… Among the eight services evaluated, the police and the judiciary are seen as the two most bribery prone. For those interacting with the judiciary, … 24% [report having paid a bribe]..

Bribery rates by service: Percentage of people who have paid a bribe to each service (average across 95 countries3)

In the past 12 months, when you or anyone living in your household had a contact or contacts with one of eight services, have you paid a bribe in any form?

Reported bribes paid to the judiciary have increased significantly [compared with the 2010/2011 Report] in some parts of the world going up by more than 20% in Ghana, Indonesia, Mozambique, Solomon Islands and Taiwan…. In 20 countries [Afghanistan, Albania, Algeria, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Bulgaria, Cambodia, Croatia, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Georgia, Kosovo, Kyrgyzstan, Lithuania, Madagascar, Moldova, Peru, Serbia, Slovakia, Tanzania and Ukraine], people believe the judiciary to be the most corrupt institution. In these countries [where data was available], an average of 30% of people who came into contact with the judiciary report having paid a bribe.

LOEWEN GROUP v. UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

Award in ICSID Case No. ARB(AF)/98/3 (NAFTA) of 26 June 2003

This dispute arises out of litigation brought against first Claimant, the Loewen Group, Inc. (“TLGI”) and the Loewen Group International, Inc. (“LGII”) (collectively called “Loewen”), its principal United States subsidiary, in Mississippi State Court by Jeremiah O’Keefe Sr. (Jerry O’Keefe), his son and various companies owned by the O’Keefe family (collectively called “O’Keefe”). The litigation arose out of a commercial dispute between O’Keefe and Loewen which were competitors in the funeral home and funeral insurance business in Mississippi. The dispute concerned three contracts between O’Keefe and Loewen said to be valued by O’Keefe at $980,000 and an exchange of two O’Keefe funeral homes said to be worth $2.5 million for a Loewen insurance company worth $4 million approximately. The action was heard by Judge Graves (an African-American judge) and a jury. Of the twelve jurors, eight were African-American.

The Mississippi jury awarded O’Keefe $500 million damages, including $75 million damages for emotional distress and $400 million punitive damages. The verdict was the outcome of a seven-week trial in which, according to Claimants, the trial judge repeatedly allowed O’Keefe’s attorneys to make extensive irrelevant and highly prejudicial references

(i) to Claimants’ foreign nationality (which was contrasted to O’Keefe’s Mississippi roots);

(ii) race-based distinctions between O’Keefe and Loewen; and (iii) class-based distinctions between Loewen (which O’Keefe counsel portrayed as large wealthy corporations) and O’Keefe (who was portrayed as running family-owned businesses). Further, according to Claimants, after permitting those references, the trial judge refused to give an instruction to the jury stating clearly that nationality-based, racial and class-based discrimination was impermissible..

Having read the transcript and having considered the submissions of the parties with respect to the conduct of the trial, we have reached the firm conclusion that the conduct of the trial by the trial judge was so flawed that it constituted a miscarriage of justice amounting to a manifest injustice as that expression is understood in international law..

O’Keefe’s case at trial was conducted from beginning to end on the basis that Jerry O’Keefe, a war hero and “fighter for his country,” who epitomised local business interests, was the victim of a ruthless foreign (Canadian) corporate predator. There were many references on the part of O’Keefe’s counsel and witnesses to the Canadian nationality of Loewen (“Ray Loewen and his group from Canada”). Likewise, O’Keefe witnesses said that Loewen was financed by Asian money, these statements being based on the fact that Loewen was partly financed by the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank, an English and Hong Kong bank which was erroneously described by Jerry O’Keefe in evidence as the “Shanghai Bank.” Indeed, Jerry O’Keefe, endeavouring to justify an earlier advertising campaign in which O’Keefe had depicted its business under American and Mississippi flags and Loewen under Canadian and Japanese flags, stated that the Japanese may well control both the “Shanghai Bank” and Loewen but he did not know that. O’Keefe’s strategy of presenting the case in this way was linked to Jerry O’Keefe’s fighting for his country against the Japanese and the exhortation in the closing address of Mr Gary (lead counsel for O’Keefe) to the jury to do their duty as Americans and Mississippians. This strategy was calculated to appeal to the jury’s sympathy for local home-town interests as against the wealthy and powerful foreign competitor.

Several additional examples will serve to illustrate this strategy. In the voir dire and opening statements, Mr Gary stated that he had “teamed up” with Mississippi lawyers “to represent one of your own, Jerry O’Keefe and his family.” Mr Gary also stated: “The Loewen Group, Ray Loewen, Ray Loewen is not here to-day. The Loewen Group is from Canada. He’s not here to-day. Do you think that every person should be responsible and should step up to the plate and face their own actions? Let me see a show of hands if you feel that everybody in America should have the responsibility to do that.” Whilst the conduct of the voir dire may not in itself have been conspicuously out of line with practice in Mississippi State courts, the skilful use by counsel for Claimants of the opportunity to implant inflammatory and prejudicial materials in the minds of the jury set the tone for the trial when it actually began.

In the voir dire O’Keefe’s counsel sought an assurance from potential jurors that they would be willing to award heavy damages. Once again, in their opening statements, O’Keefe’s counsel urged the jury to exercise “the power of the people of Mississippi” to award massive damages. O’Keefe’s counsel drew a contrast between O’Keefe’s Mississippi antecedents and Loewen’s “descent on the State of Mississippi.”

Emphasis was constantly given to the Mississippi antecedents and connections of O’Keefe’s witnesses. By way of contrast Mr Gary, in cross-examination of Raymond Loewen, repeatedly referred to his Canadian nationality, noted that he had not “spent time” in Mississippi and questioned him about foreign and local funeral home ownership. Jerry O’Keefe, in his evidence, pointed out that Loewen was a foreign corporation, its “payroll checks come out of Canada” and “their invoices are printed in Canada.”

An extreme example of appeals to anti-Canadian prejudice was evidence given by Mr Espy, former United States Secretary of State for Agriculture who, called to give evidence of the good character of Jerry O’Keefe, spoke of his (Espy’s) experience in protecting “the American market” from Canadian wheat farmers who exported low priced wheat into the American market with which American producers could not compete and later, having secured a market, then jacked up the price..

The strategy of emphasizing O’Keefe’s American nationality as against Loewen’s Canadian origins reached a peak in Mr Gary’s closing address. He likened Jerry O’Keefe’s struggle against Loewen with his war-time exploits against the Japanese, asserting that he was motivated by “pride in America” and “love for your country.” By way of contrast, Mr Gary characterized Loewen’s case as “Excuse me, I’m from Canada.” Indeed, Mr Gary commenced his closing address by emphasizing nationalism: “[Y]our service on this case is higher than any honor that a citizen of this country can have, short of going to war and dying for your country.” He described the American jury system as one that O’Keefe “fought for and some died for.” Mr Gary said “they [Loewen] didn’t know that this man didn’t come home just as an ace who fought for his country—he’s a fighter…. He’ll stand up for America and he has.”

Mr Gary returned to the same theme at the end of his closing address: “[O’Keefe] fought and some died for the laws of this nation, and they’re [Loewen] going to put him down for being American.” Mr Gary reminded the jury that many of O’Keefe’s witnesses were Mississippians. On the other hand, Mr Gary characterized Loewen as a foreign invader who “came to town like gang busters. Ray came sweeping through….” Mr Gary even repeated the prejudicial evidence given by Mr Espy about the Canadian wheat farmers. Mr Gary likened Loewen to the Canadian wheat farmers. Loewen would “come in” and purchase a funeral home and “no sooner than they got it, they jacked up the prices down here in Mississippi.”…

Claimants further complain that Mr Gary repeatedly portrayed Loewen as a large, wealthy foreign corporation and contrasted Jerry O’Keefe as a small, local, family businessman. There were a number of references by O’Keefe’s counsel emphasizing this contrast. These references culminated in Mr Gary’s closing address in which he incited the jury to put a stop to Loewen’s activities. Speaking of Jerry O’Keefe, Mr Gary said:

“He doesn’t have the money that they have nor the power, but he has heart and character, and he refused to let them shoot him down.” …

“Ray comes down here, he’s got his yacht up there, he can go to cocktail parties and all that, but do you know how he’ s financing that? By 80 and 90 year old people who go to get to a funeral, who go to pay their life savings, goes into this here, and it doesn’t mean anything to him. Now, they’ve got to be stopped…. Do it, stop them so in years to come anybody should mention your service for some 50 odd days on this trial, you can say ‘Yes, I was there,’ and you can talk proud about it.”

“1 billion dollars, ladies and gentlemen of the jury. You’ve got to put your foot down, and you may never get this chance again.” …

When the trial is viewed as a whole right through from the voir dire to counsel’s closing address, it can be seen that the O’Keefe case was presented by counsel against an appeal to home-town sentiment, favouring the local party against an outsider. To that appeal was added the element of the powerful foreign multi-national corporation seeking to crush the small independent competitor who had fought for his country in World War II. Describing “Loewen” as a Canadian was simply to identify Loewen as an outsider. The fact that an investor from another state, say New York, would or might receive the same treatment in a Mississippi court as Loewen received is no answer to a claim that the O’Keefe case as presented invited the jury to discriminate against Loewen as an outsider

TREATY OF WASHINGTON

Articles I-VI, X (1871)

[excerpted in Documentary Supplement at pp. 65–68]

[During the U.S. Civil War, the Confederacy contracted with English ship-builders to construct several warships in English shipyards. The United States protested to the United Kingdom, claiming that construction of the vessels was a violation of U.K. obligations of neutrality towards the United States. Despite the U.S. protests, the vessels left English ports and subsequently were manned by Confederate sailors, who inflicted substantial losses on U.S. shipping (sinking or capturing roughly 100 cargo ships). The most formidable of the Confederate vessels, named the Alabama, successfully attacked U.S. vessels in waters around the world, before finally being sunk, towards the end of the Civil War, by Union warships.

After the Civil War concluded, the United States demanded compensation from the United Kingdom, claiming that the U.K. acquiescence and tacit support for construction of the Alabama and other vessels resulted in massive damage to the United States, including the value of cargo vessels that were sunk or captured, the lost cargo (which was allegedly diverted from U.S. vessels to “safer” foreign vessels (primarily U.K. vessels)), and the costs of an allegedly prolonged war. The United Kingdom rejected the U.S. demands, provoking bitter diplomatic and political disputes. The two states eventually agreed, in the 1871 Treaty of Washington, to refer this dispute (and other disputes) to international arbitration. Pursuant to the Treaty, the United States and United Kingdom conducted the so-called “Alabama Arbitration” (seated in Geneva), which produced an award partially upholding the U.S. claims. The background of the Treaty of Washington and the ensuing arbitration are described in Bingham, The Alabama Claims Arbitration, 54 Int’l & Comp. L.Q. 1 (2005) and F. Hackett, Reminiscences of the Geneva Tribunal of Arbitration

(1911).]

1907 HAGUE CONVENTION FOR THE PACIFIC SETTLEMENT OF INTERNATIONAL DISPUTES

Articles 37, 38, 40, 41

[excerpted in Documentary Supplement at p. 43]

ARBITRATION AGREEMENT BETWEEN THE GOVERNMENT OF SUDAN AND THE SUDAN PEOPLE’S LIBERATION MOVEMENT/ARMY ON DELIMITING THE ABYEI AREA

Articles 1-3 (2008) (also excerpted in Documentary Supplement at pp. 79–80)

[Since Sudan’s independence in 1954, the country was engulfed by almost continuous civil war, generally pitting the largely Muslim, Arabic-speaking north against the primarily Christian and other non-Muslim south. In 2004, the Government of Sudan (“GoS”) and the Sudan Peoples’ Liberation Movement/Army (“SPLM/A”), the principal Sudanese resistance group, negotiated and signed a Comprehensive Peace Agreement (“CPA”). The CPA, concluded under United Nations auspices, aimed at ending the civil war and permitting a referendum in which southern Sudan could decide whether or not to form an independent state.

A central issue addressed by the CPA was the status of a territory located in south-central Sudan, called the Abyei Area, which lay on the border between southern and northern Sudan. Among other disputes, the GoS and SPLM/A disagreed about the territorial boundaries of the Abyei Area. The CPA provided for the Abyei Area to be delimited by a commission of experts (the Abyei Boundaries Commission (“ABC Experts”)). After extensive submissions from the parties, the ABC Experts issued a report in July 2005 delimiting boundaries for the Abyei Area. Dissatisfied with the result, the GoS refused to accept the Report, leading to a prolonged stalemate with the SPLM/A, which threatened the broader peace process envisaged by the CPA.

The stalemate between the GoS and the SPLM/A was broken in July 2008, when the two parties agreed to arbitrate their disagreements regarding the ABC Experts Report and the boundaries of the Abyei Area. The parties’ agreement is excerpted in the Documentary Supplement at pp. 79–84.

The Abyei Arbitration Agreement, and the resulting Abyei Arbitration, are described in materials on the website of the Permanent Court of Arbitration, under whose auspices the arbitration was conducted. Among these materials are the parties’ written submissions, webcasts of the oral proceedings and the arbitral award made by the tribunal. See www.pca-cpa.org; www.wx4all.net/pca.]

RAINBOW WARRIOR AFFAIR

(1985)

[In July 1985, agents of the French Directorate General of External Security (“DGSE”) planted mines on the “Rainbow Warrior,” a protest vessel belonging to Greenpeace (an environmental advocacy group), when it was moored in Auckland Harbour, New Zealand. The vessel had been scheduled to sail to Mururoa Atoll, in French Polynesia, to protest against French nuclear testing; that voyage was prevented by the actions of the DGSE agents, which resulted in the vessel’s sinking (and the death of one Greenpeace member). Criminal investigations by New Zealand police resulted in the arrests of two French DGSE agents (and their subsequent criminal convictions). France initially denied responsibility for the attack on the Rainbow Warrior and imposed economic sanctions on New Zealand in retaliation for the DGSE agents’ arrest. Subsequently, however, France acknowledged responsibility for the sinking of the Rainbow Warrior and offered to pay reparations to both New Zealand and Greenpeace.

Despite negotiations between France and, respectively, New Zealand and Greenpeace, no agreement could be reached on reparations. As a consequence, France and New Zealand concluded an arbitration agreement, submitting disputes about reparations and treatment of the DGSE agents to the Secretary-General of the United Nations for resolution. After receiving written submissions from the parties, the Secretary-General rendered an award requiring France to formally apologize to New Zealand and to pay New Zealand $7 million (including for moral damage); he also ordered the transfer of the two DGSE agents to “an isolated island outside of Europe for a period of three years.” See United Nations Secretary General: Ruling on the Rainbow Warrior Affair Between France and New Zealand, 26 I.L.M. 1346 (1987).

In parallel, France and Greenpeace concluded a separate arbitration agreement, submitting the question of France’s financial liability for the sinking to an arbitral tribunal seated in Geneva, Switzerland. The tribunal was composed of Professor Claude Reymond, a Swiss law professor, Sir Owen Woodhouse, a retired New Zealand judge, and Professor Francois Terre, a French law professor. After receiving written submissions and conducting an evidentiary hearing, the tribunal rendered an award requiring France to pay Greenpeace $5 million in damages, $1.2 million for “aggravated damages,” and $2 million in expenses, interest and legal fees. See Shabecoff, France Must Pay Greenpeace $8 Million in Sinking of Ship, N.Y. Times (Oct. 3, 1987). Following the award, the chairman of Greenpeace, David McTaggart, said that the decision “is a great victory for those who support the right of peaceful protest and abhor the use of violence.” Ibid. The text of the arbitral award remains confidential.]

BUHRING-UHLE, A SURVEY ON ARBITRATION AND SETTLEMENT IN INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS DISPUTES

in C. Drahozal & R. Naimark (eds.), Towards A Science of International Arbitration 25, 31-33 (2005)

Clearly the two most significant advantages and presumably the two most important reasons for choosing arbitration as a means of international commercial dispute resolution seem to be the neutrality of the forum, i.e., the possibility to avoid being subjected to the jurisdiction of the home court of one of the parties, and the superiority of its legal framework, with treaties like the New York Convention guaranteeing the international enforcements of awards. Both attributes were thought to be “highly relevant” or “significant” by over 80% of the individuals responding, and in each case only 3 respondents (5%) thought that there really was no advantage.

On the scale from -1 (“advantage does not exist”) to 3 (“highly relevant”), the aggregate of the answers with respect to the significance of both the neutrality of forum and the international enforceability of awards amounted to 2.4, which places both considerations on aggregate almost exactly halfway between “significant” and “highly relevant.”

The next most important advantages were, by order of relevance, the confidentiality of the procedure, the expertise of the tribunal, the absence of appeals, and the limited discovery available in international commercial arbitration. Each of these four considerations was deemed “highly relevant” or “significant” by a clear majority (close to or over 60%) of the respondents. Within this group of arbitration advantages, the confidentiality of the procedure was the one least questioned (only 7% thought there was no advantage) and attained the highest average relevance, placing it close to “significant” (1.8). The other three considerations were doubted by about one fifth (between 10% and 23%) and produced average relevance values somewhere close to the midpoint between “one factor among many” and “significant”: the possibility to choose a tribunal with special expertise “scored” 1.6, the absence of appeals 1.5, and the availability of limited discovery was placed at 1.3.

The aspect of limited discovery is slightly ambivalent in that some respondents tended to compare it to the extensive discovery practiced in American courts while for others the civil law practice, which does not know discovery in the common law sense, was the point of reference. So if a relatively high number of respondents (21%) thought that the practice of limited discovery was of no advantage their motivation might have been quite different. Also, the different legal traditions of the respondents led to significant “geographical” variations in the assessment of this aspect of arbitration practice. Another slightly ambivalent attribute of arbitration is the absence of appeals which by a large number of practitioners is crucial for the aim of obtaining a final decision within a reasonable time span but which, according to some of the practitioners interviewed, can also be seen as a disadvantage since the possibility to correct even grave errors of the arbitral tribunal is very restricted. Accordingly, this was the aspect that within this group of four arbitration advantages of some significance received the highest percentages both in the category “highly relevant” (37%) and “advantage does not exist” (23%).

Attributes of international commercial arbitration that, on aggregate were only regarded as slight advantages somewhere between “one factor among many” and “not relevant” were the expedience of the procedure, its amicability and the presumably greater degree of voluntary compliance with the results. In each case the number of respondents considering this attribute to be a “highly relevant” or “significant” advantage did not exceed 40% and was surpassed by the number of respondents who thought the advantage was non-existent. The average relevance was 0.7 for both the presumably greater speed and amicability of arbitration, and 0.5 for the supposedly higher degree of voluntary compliance with arbitral awards.

The two least significant of the 11 hypothetical advantages offered in the questionnaire were the presumably lower costs of the procedure, which on balance was regarded as irrelevant, and the predictability of its results which figured midway between irrelevant and non-existing. More than half (51%) of the respondents thought that the cost advantage did not exist and three quarters (75%) doubted that the results were more predictable. The aggregate significance amounted to 0.2 for the hypothetical cost advantage and -0.5, the lowest overall value of all the considerations discussed, for the supposedly greater predictability of results.

15 of the individuals responding specified a total of 8 “other” reasons why arbitration is chosen over litigation:

• the most frequently cited reason, which was mentioned five times, was the possibility for the parties to select the members of the tribunal themselves;

• next with four mentions was the perception that in international commercial disputes there really was no alternative to arbitration;

• then came with three mentions each the greater flexibility of the procedure and

• the possibility to choose the language of the procedure;

• attributes mentioned twice were the preservation of business relationships and

• the fact that arbitration constitutes a “de luxe” form of litigation;

• one mention each was given to the special expertise of the arbitrators in the applicable foreign law and

• the possibility to conduct a procedure less burdened by technicalities.

QUEEN MARY, UNIV. OF LONDON, INTERNATIONAL ARBITRATION SURVEY: CORPORATE CHOICES IN INTERNATIONAL ARBITRATION

Earlier surveys by Queen Mary, University of London, had confirmed arbitration’s overall popularity. In the 2008 survey, 86% of respondents said they were “satisfied” with arbitration. Likewise in 2006, 73% of participants identified international arbitration as their preferred mechanism for dispute resolution….

Arbitration ranked first more often than any of the other mechanisms (52% of respondents marked arbitration as most preferred). Arbitration was also ranked last less often than any other mechanism. Almost the same proportion of participants prefer arbitration when they are claimants (62%) as when they are respondents and have no counterclaim (60%)….

While, overall, arbitration remains the preferred dispute resolution mechanism for transnational disputes, many respondents and interviewees expressed concern over the related issues of costs and delays experienced in international arbitration proceedings….

Interviewees [also] expressed concern about their perception that the process of arbitration has become more sophisticated and more “regulated,” with “control” over the process moving towards law firms—and away from the actual users of this process. Several interviewees linked concerns over increases in the costs of arbitration with this encroaching judicialisation.

Overall, however, both the survey and our interviews showed a continued support for arbitration, and an expectation that respondents will keep using this mechanism in the future.

UNITED KINGDOM/BOSNIA-HERZEGOVINA BIT

Articles 8, 9

[excerpted in Documentary Supplement at pp. 76–77]

NOTES

1. Relative costs and speed of commercial arbitration and litigation. The costs and efficiency of different dispute resolution mechanisms vary from time to time and place to place. Nonetheless, there have been recurrent complaints from commercial users, as well as individuals, about the delays and expenses imposed by many national court systems. Consider the complaints from the ancient Egyptian records, excerpted above from Crum and Steindorff. Compare them to the complaints from early colonial America.

Is it possible to say that arbitration is necessarily quicker and cheaper than litigation in national courts? Doesn’t that inevitably depend on how quickly each of the respective dispute resolution processes can proceed? Note that some commentators and users characterize arbitration as the slower, more expensive alternative. Blue Tee Corp. v. Koehring Co., 999 F.2d 633 (2d Cir. 1993) (“this appeal … makes one wonder about the alleged speed and economy of arbitration in resolving commercial disputes”); Lyons, Arbitration: The Slower, More Expensive Alternative, Am. Law. 107 (Jan./Feb. 1985); Queen Mary, University of London, 2013 International Arbitration Survey: Corporate Choices in International Arbitration (2013). Compare the views of business users, reported by Buhring-Uhle.

In considering the relative cost and speed of international arbitration versus litigation, it is important to take into account the likelihood of jurisdictional disputes and parallel proceedings. Suppose a Japanese and a French company enter into a long-term sales agreement, which leads to disputes. Assuming there is no agreement to arbitrate such disputes, what is likely to occur after efforts to amicably settle the disputes fail? Where is the Japanese company likely to want the parties’ disputes resolved? What about the French company? What happens if both companies pursue their favored means of dispute resolution? What happens if each company succeeds in obtaining a judgment in its favor from its local courts?

In considering the relative speed and cost of international arbitration, note also that parties are generally permitted to impose contractual time limits on the arbitral process (e.g., by requiring an award to be made within a specified time period from the commencement of the arbitration). Is this ordinarily possible in national court proceedings?

2. Absence of appellate review. In addition to other factors affecting the costs and delays of different forms of dispute resolution, consider the possibility of appeals from first-instance judgments in national courts. In some jurisdictions, such appeals are essentially de novo re-litigations; in other jurisdictions, decisions of law are subject to de novo review, while reviews of factual finding are subject to more deferential appellate scrutiny. In contrast, in most developed jurisdictions, international arbitral awards are subject to only very limited judicial review (ordinarily only on issues of jurisdiction, procedural unfairness, or public policy), not extending to the merits of the arbitral tribunal’s decision. Consider, in this regard, Article 34 of the UNCITRAL Model Law, excerpted at pp. 94–95 of the Documentary Supplement. Note that the possibility of de novo or otherwise extensive appellate review materially increases the possibility of delays and additional costs.

Is it desirable for there to be no or de minimis appellate review of an arbitrator’s decisions? Does not appellate review provide an important check against arbitrary decision-making and erroneous conclusions? Is it worth giving up this check in order to obtain other benefits?

3. Party autonomy with regard to arbitral procedures and selection of arbitrators. One of the advantages of the arbitral process, both international and domestic, is the parties’ autonomy to design their own dispute resolution procedures and to select their own arbitral tribunal. Parties can agree upon a “fast-track” arbitration, to be completed in a matter of weeks or months; they can agree to a “documents only” arbitration, which involves no oral testimony; or they can agree to an arbitral tribunal that includes technical experts. For the most part, such choices are not available in national courts.

In a number of national and international industries, specialized arbitral institutions and dispute resolution mechanisms have been designed by market players and trade associations. That is true, for example, in maritime, commodities, insurance and reinsurance, construction and other markets, where specialized arbitral institutions with specialized arbitration rules have developed. See, e.g., AAA Labor Arbitration Rules; AAA Rules for Impartial Determination of Union Fees; 2014 National Grain and Feed Association Arbitration Rules (selected commodities disputes); 2012 London Maritime Arbitration Association Terms (maritime); ARIAS U.S. Rules for the Resolution of U.S. Insurance and Reinsurance Disputes.

How important is it for parties to be able to select their own procedural rules? Can parties do so in national courts? Why should they want to do so? Why should they be permitted to do so? Consider the following observations:

“For a French party, the big advantage is that international commercial arbitration offers ‘de luxe justice.’ … Instead of having a $600 million dispute before the commercial court in Paris, where each party has only one hour for pleading and where you can’t present witnesses and have no discovery; for a dispute of that importance it may well be worth the costs to get a type of justice that is more international and more ‘luxurious’; what you get is more extensive and thorough examination of witness testimony—without the excesses of American court procedure.” Buhring-Uhle, A Survey on Arbitration and Settlement in International Business Disputes, in C. Drahozal & R. Naimark (eds.), Towards A Science of International Arbitration: Collected Empirical Research 34 & n. 28 (2005).

Is it appropriate to permit parties to agree upon “de luxe” justice? On “rough” justice? On specialized procedures? Is it appropriate to forbid parties from doing so?

4. Commercial or other expertise of arbitrators. Related to the parties’ autonomy to select “their” arbitral tribunal is the commercial (and other) expertise of arbitrators, as compared to national courts. Are parties permitted to select “their” judge in national court proceedings? Should they be?

Note also that many judges in national courts are generalists, hearing civil, criminal, domestic and other disputes and often having no commercial experience (either in business or as a practicing lawyer advising businesses). In contrast, parties often select arbitrators with specific and extensive experience in the subject-matter and/or law of their dispute (e.g., arbitrators with experience in construction, joint ventures, insurance, or maritime disputes). This experience and expertise enhance the predictability and commercial reasonableness of the tribunal’s ultimate decision. Compare the observations of the former president of the French Cour de cassation, explaining why he regarded arbitration as desirable: “[F]irst, what you do we don’t have to do; … [s]econd, in many fields you are more professional than we are.” Lazareff, International Arbitration: Towards A Common Procedural Approach, in S. Frommel & B. Rider (eds.), Conflicting Legal Cultures in Commercial Arbitration 31, 33 (1999). Note also that parties can include contractual requirements in their arbitration agreement, specifying that the arbitrators have particular experience or qualifications. See infra pp. 710–16. For example, parties to an insurance or reinsurance policy can require that the arbitrator be an insurance practitioner, or a former insurance industry employee; parties to a telecommunications supply contract can require that the arbitrators have experience in that industry; parties to an oil and gas contract can require that the arbitrators have experience with oil and gas disputes. Alternatively, parties can agree to arbitrate under specialized institutional rules, tailored to particular industries (and having institutional lists of arbitrators with specialized expertise and experience). See supra pp. 70–71, 109–10.

5. Neutrality of tribunal. Recall the hypothetical above, where Japanese and French parties conclude a contract, which leads to disputes. Is it likely that the Japanese party would wish for disputes to be resolved in French courts? That the French party would be willing to have disputes resolved in Japanese courts? Why not? Consider the excerpts from the Transparency International report and the Loewen award. If you were a non-U.S. party, how comfortable would you be having your disputes resolved in U.S. courts? Are U.S. courts unusually bad, in terms of parochialism or “hometown” bias, compared to courts in other countries? How comfortable would you be having your own disputes resolved in one of the twenty countries identified in the Transparency International report?

One of the perceived advantages of international arbitration is that it permits parties to select a neutral decision-maker—which is not part of the governmental structure of either party’s home state and which is not composed of nationals of either party’s home jurisdiction. Alternatively, the parties can each select a co-arbitrator of their choice (including a co-arbitrator with the party’s own nationality), while requiring the presiding arbitrator to have a neutral nationality. For example, in the hypothetical involving French and Japanese parties, the tribunal could be comprised of a French, a Japanese and a U.S. or Canadian (presiding) arbitrator. How important is the neutrality of the decision-maker in international disputes? Note the provisions regarding constitution of the tribunal in the Treaty of Washington and the Abyei Arbitration Agreement.

6. Enforceability of international arbitration agreements. Consider Article II of the New York Convention, excerpted at p. 1 of the Documentary Supplement. As noted above, as of 2014, some 153 countries are Contracting States to the Convention. See supra pp. 33–39, 44. Article II of the Convention obligates Contracting States to recognize international arbitration agreements and to enforce such agreements by referring their parties to arbitration. What is the practical importance of the obligation imposed by Article II of the Convention?

Consider the terms of the proposed Hague Convention on Choice of Court Agreements, excerpted at pp. 53–63 of the Documentary Supplement, which was drafted under the auspices of the Hague Conference on Private International Law. The Convention has not come into force yet, nor been implemented in the states which have ratified it. On January 30, 2014, the European Commission published a proposal for approval by the EU of the Hague Convention; if the proposal is adopted, the Convention will in due course enter into force between the EU and Mexico. See G. Born, International Commercial Arbitration 79 (2d ed. 2014). When the Convention does come into force, what effect will it have on the “enforceability premium” enjoyed by international arbitration agreements? Note the exceptions in Articles 2 and 9 of the proposed Convention.

7. Enforceability of international arbitral awards. Consider the excerpt from Bloch, regarding international dispute resolution in Europe during the Middle Ages. Similar issues arise today, in obtaining effective recognition of national court judgments in other states. Note that difficulties in enforcing national court judgments are particularly likely where there have been parallel proceedings and jurisdictional disputes in different national courts.

Consider Articles III and V of the New York Convention, excerpted at pp. 1–2 of the Documentary Supplement. What do they provide, in general terms, with regard to the recognition and enforcement of foreign arbitral awards? Note that there is currently no comparable multilateral treaty providing for the recognition and enforcement of foreign court judgments. As a consequence, it is fair to say that international arbitral awards enjoy an “enforceability premium,” as compared to national court judgments. How important is that consideration in determining whether or not to agree to an international arbitration agreement?

Consider again the proposed Hague Convention on Choice of Court Agreements, excerpted at pp. 53–63 of the Documentary Supplement. What does it provide with regard to the recognition of foreign judgments? To what extent would it affect the “enforceability premium” currently enjoyed by arbitral awards?

8. Confidentiality. As discussed in detail below, many international arbitrations are confidential. See infra pp. 851, 866–68. In most cases, the filings and hearings in an international commercial arbitration are not available to non-parties (or the press), and neither party is free to disclose such materials (or other information about the arbitration) to third parties. Consider the views of business users of arbitration, reported in the Buhring-Uhle study, regarding confidentiality. Why might it be important for commercial parties that their disputes remain confidential? To what extent may publicity of a dispute prevent its amicable resolution?

9. International forum selection agreements. A potential alternative to an international arbitration agreement is a forum selection clause. A forum selection clause specifies a national court for the resolution of the parties’ disputes; the clause may be either exclusive (requiring resolution of all disputes exclusively in the specified contractual forum) or non-exclusive (permitting either party to pursue litigation in the specified contractual forum, but not precluding litigation in other forums). See G. Born & P. Rutledge, International Civil Litigation in United States Courts 462-63 (5th ed. 2011).

To what extent is a forum selection clause a satisfactory alternative to an arbitration agreement? Does a forum selection clause have the potential to impose contractual time limits on the length of a litigation? Can parties to a forum selection clause select the specific judge that they desire to decide their case? Can they insist that the judge have specified experience? Can the parties to a forum selection clause specify their own procedures and procedural timetable for “their” litigation? What is the relative enforceability of international arbitration agreements and international forum selection agreements? International arbitral awards and foreign court judgments?

Consider again the hypothetical concerning Japanese and French parties to a contract. Suppose the parties entertain the possibility of adopting a forum selection clause. What national courts should the parties choose? French? Japanese? If not the courts of either party, then what courts? What rationale is there for selecting, for example, an English, Swiss, Singaporean, or U.S. court? How do such courts compare to selecting an arbitral tribunal?

10. Arbitration as means of resolving state-to-state disputes. Consider Article 38 of the 1907 Hague Convention, excerpted at p. 43 of the Documentary Supplement. What aspects of arbitration led states to conclude that “international arbitration” is “recognized by the signatory powers as the most effective, and at the same time the most equitable, means of settling disputes which diplomacy has failed to settle”? This is robust praise for the international arbitral process. What warrants it? Recall the discussion above of the use of international arbitration historically to resolve inter-state disputes. See supra pp. 2–10. Consider the limitations referred to in Article 38. Why are they included?

Consider the 1871 Treaty of Washington, which provided the basis for the Alabama Arbitration. Why did the United States and Great Britain decide to resolve their dispute by international arbitration? What were the alternatives? Consider the various procedural terms of the Treaty of Washington. What did the arbitral process permit the parties to accomplish? See also T. Balch, The Alabama Arbitration (1900); Bingham, The Alabama Claims Arbitration, 54 Int’l & Comp. L.Q. 1 (2005); F. Hackett, Reminiscences of the Geneva Tribunal of Arbitration (1911).

Consider the Abyei Arbitration Agreement. Why did the Government of Sudan and the Sudan Peoples’ Liberation Movement/Army decide to resolve their disputes over Abyei by international arbitration? Again, what were the alternatives? Note the various procedural terms of the Abyei Arbitration Agreement, including the expedited timetable, the provisions for selection of the tribunal and provisions regarding publicity. What role did these provisions play in enabling the parties to resolve their dispute?

Consider the Greenpeace arbitration. Why do you think Greenpeace and France agreed to resolve their dispute by arbitration? Again, what were the alternatives? What advantages did arbitration offer to Greenpeace? To France?

11. Arbitration as a means of resolving investment disputes. Consider the facts in the Loewen case. Why is it that Canadian (or other foreign) investors in the United States might wish for their investment disputes to be resolved in a forum other than U.S. courts? Are U.S. courts uniquely inhospitable to foreign investors? Why might a U.S. investor in Canada want its investment disputes resolved in a forum other than Canadian courts? If a forum other than national courts is to resolve investment disputes, what forum might that be? Consider the U.K./Bosnia-Herzegovina BIT. What use does it make of international arbitration as a means of resolving investment disputes? Compare the ICSID Convention.

12. Contemporary popularity of international arbitration. International arbitration has demonstrated considerable popularity as a means of dispute resolution over the past century. Recall again Article 38 of the 1907 Hague Convention. Also recall the nearly global acceptance of the New York Convention and the ICSID Convention.

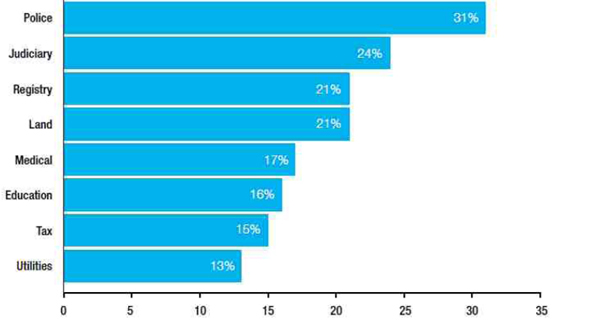

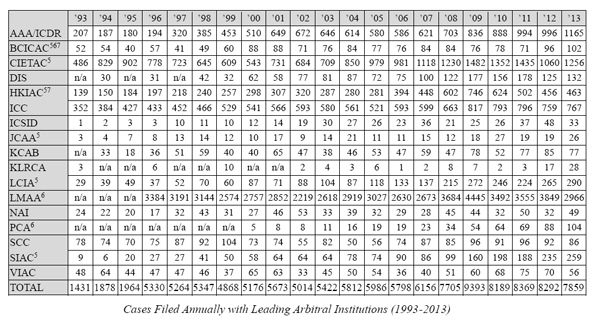

The popularity of international arbitration is reflected in steadily-increasing caseloads at leading arbitral institutions, with the number of reported cases increasing between two-fold and ten-fold in the past 20 years. Among other things, the International Chamber of Commerce’s International Court of Arbitration received requests for 32 new arbitrations in 1956, 210 in 1976, 337 in 1992, 452 in 1997, 529 in 1999, 593 in 2006 and 767 in 2013—a roughly 24-fold increase over the past 60 years. Similarly, in 1980, the AAA/ICDR administered 101 international arbitrations; 207 in 1993, 453 in 1999, 586 in 2006 and 996 in 2012. Other institutions show similar growth in caseloads, as illustrated in the following table, which shows the number of new international arbitration cases filed with leading arbitral institutions between 1993-2013.4

What explains the popularity of international arbitration as a means of dispute resolution? Is it because international arbitration is so good? Or that it is better than the alternatives? Something else?

B. JURISDICTIONAL REQUIREMENTS FOR INTERNATIONAL ARBITRATION AGREEMENTS UNDER INTERNATIONAL ARBITRATION CONVENTIONS AND NATIONAL ARBITRATION LEGISLATION

As discussed elsewhere, the substantive terms of the New York Convention and most contemporary national arbitration statutes (again, such as the UNCITRAL Model Law) are “pro-arbitration,” providing effective and robust mechanisms for enforcing international arbitration agreements and arbitral awards.8 In particular, Article II of the Convention imposes obligations on Contracting States to recognize international arbitration agreements and to enforce them by referring the parties to arbitration;9 similarly, Articles 7, 8 and 16 of the UNCITRAL Model Law provide parallel treatment of specified international arbitration agreements.10 In addition, both international arbitration conventions and national arbitration statutes contain jurisdictional requirements that define what arbitration agreements and arbitral awards are (and are not) subject to those instruments’ substantive rules. These requirements have important consequences, because they determine when the pro-enforcement regimes of the New York Convention and many national arbitration statutes are applicable—rather than other means of enforcement, which are sometimes archaic and often ineffective.

Despite the importance of the issue, defining precisely which international arbitration agreements are subject to the New York Convention is not always straightforward. As discussed in detail below, Article I of the Convention specifically defines those arbitral awards that are subject to the Convention.11 In contrast, nothing in Article II of the Convention (or otherwise) expressly addresses which arbitration agreements are subject to Article II’s “recognition” requirement. In the words of one commentator: “[T]he Convention does not give a definition as to which arbitration agreements fall under [Article II].”12

The jurisdictional requirements of the New York Convention impose non-trivial limitations on the scope of the Convention. There are numerous international arbitration agreements to which the New York Convention does not apply: “[T]here is a vast area not covered by the Convention.”13 In particular, five jurisdictional requirements of the New York Convention warrant attention.14

First, Article II(1) and II(2) limit the Convention’s coverage to “arbitration agreement[s]” and “arbitral clause[s],” as distinguished from other types of agreements (e.g., mediation or choice-of-court agreements). Second, where Contracting States have adopted a reservation to this effect, the Convention is generally applicable only to differences arising out of “commercial” relationships. Third, again pursuant to Article II(1), the parties’ agreement must provide for arbitration of “differences which have arisen or which may arise … in respect of a defined legal relationship, whether contractual or not.” Fourth, the Convention is applicable in many national courts only on the basis of reciprocity (i.e., vis-à-vis other nations that also have ratified the Convention). Finally, the Convention arguably applies only to agreements concerning “foreign” or “nondomestic” awards or, alternatively, to international arbitration agreements.

Like the New York Convention, contemporary international arbitration statutes in most states contain either express or implied jurisdictional limitations. As under the Convention, these jurisdictional requirements have substantial practical importance because they determine when the generally “pro-arbitration” substantive provisions of contemporary arbitration legislation apply, both to arbitration agreements and arbitral awards.

The jurisdictional requirements of national arbitration statutes vary from state to state. In general, however, these jurisdictional limits are broadly similar to those contained in the New York Convention: (a) requirements for an “arbitration agreement” (or “arbitral award”); (b) a “commercial relationship” requirement; (c) a “foreign” or “international” connection requirement; and (d) a “defined relationship” requirement. In addition, most arbitration statutes are generally (but not exclusively) applicable only to arbitrations seated in national territory. We examine each of these categories of jurisdictional requirements below, in conjunction with discussions of the parallel jurisdictional limitations under the New York Convention.

Finally, in the context of international investment arbitration, the ICSID Convention and BITs also contain significant jurisdictional limitations. In particular, both sets of instruments are addressed to the resolution of “investment” disputes, arising out of “investments” or “investment agreements” between a state and specified foreign nationals.15 These jurisdictional requirements ensure that the specialized dispute resolution mechanisms of the ICSID Convention and BITs are available only in relatively limited, precisely-defined cases.

1. Definition of “Arbitration Agreement”

Most international commercial arbitration conventions and national arbitration statutes will apply only if the parties have putatively made an agreement to “arbitrate”—as opposed to an agreement to do something else; similar provisions exist in the case of investment and state-to-state arbitrations. This raises the definitional question of what constitutes an “arbitration agreement.” For example, parties may agree to expert determination, conciliation, mediation, or other forms of alternative dispute resolution, or to a forum selection clause providing for litigation in a specified national court. Ordinarily, none of these forms of dispute resolution constitute “arbitration” within the meaning or scope of the New York Convention (or other international arbitration conventions) or national arbitration statutes.

Significant legal consequences follow under virtually all international conventions and national arbitration laws from characterization of a contractual provision as something other than an “arbitration agreement.” In these instances, the “pro-arbitration” regimes of the New York Convention and national arbitration statutes do not necessarily apply to the agreement (or any resulting decision). Rather, ordinary domestic contract law rules or specialized legislation (e.g., applicable to mediation or forum selection agreements) will apply; in most cases, these other legal regimes will be materially less effective as means of enforcement than the New York Convention and parallel national arbitration statutes.16 Given the importance of these consequences, there is a surprising lack of guidance under both international conventions and national legislation relevant to the question of what constitutes an “arbitration agreement.” The materials excerpted below explore these issues.

UNITED NATIONS CHARTER

Article 33(1)

The parties to any dispute, the continuance of which is likely to endanger the maintenance of international peace and security, shall, first of all, seek a solution by negotiation, enquiry, mediation, conciliation, arbitration, judicial settlement, resort to regional agencies or arrangements, or other peaceful means of their own choice.

JIVRAJ v. HASHWANI