12 Register Disbursement Schemes

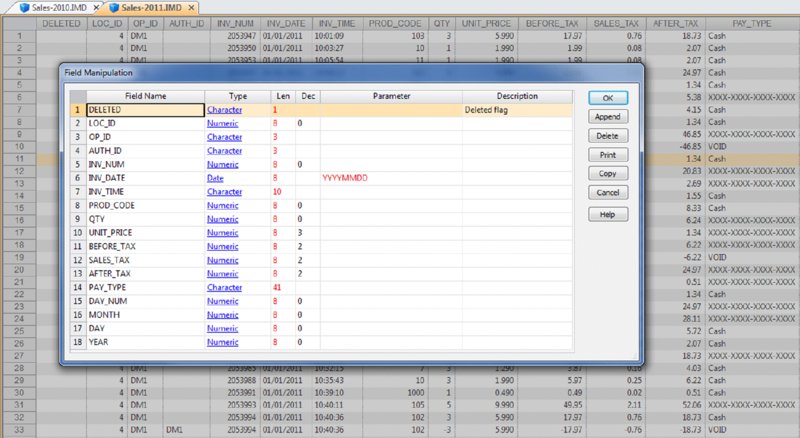

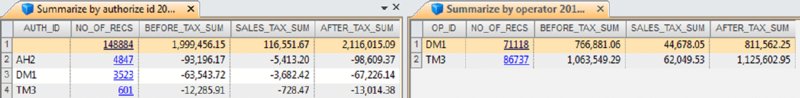

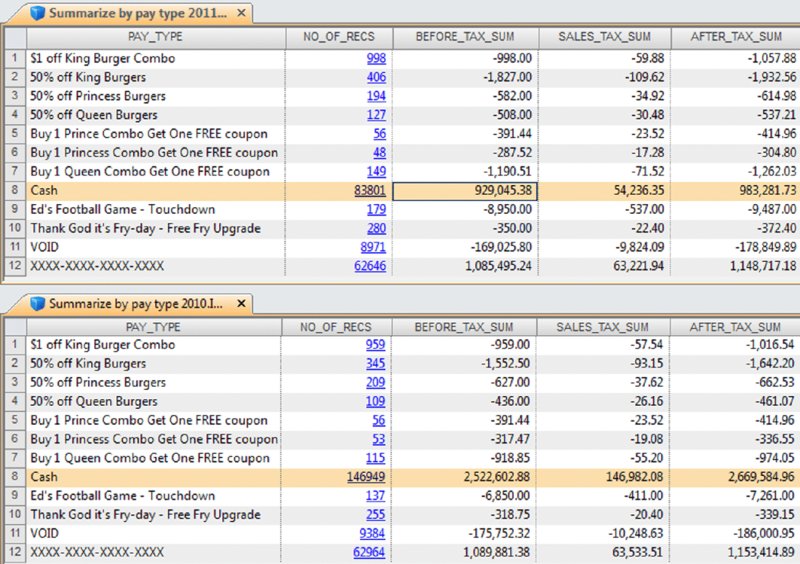

CHAPTER 12 REGISTER DISBURSEMENT SCHEMES INVOLVE fraudulent refunds and fraudulent voids where these false entries allow the removal of funds from the cash register or point-of-sales system. Register disbursement schemes differ from the skimming and cash larceny schemes discussed in Chapter 7, where funds are removed from the cash register before being recorded and leave no record of the transactions. False refunds are when no actual return of goods or pricing adjustments are made —they are merely recorded. This allows cash to be taken from the register while the cash still balances to the register records. Instead of cash, refunds can be made to the fraudster’s credit card or an accomplice’s card. Refunding to credit cards avoids other people or surveillance cameras from seeing the fraudster take cash from the register and pocketing the money. False refunds overstate the inventory of the goods. Since there are no goods actually returned to inventory, there will be inventory shortages. Some level of inventory shortages are expected and accepted as the cost of doing business but excessive and regular shortages are a cause for concern. Inventory may not be counted on a regular basis or the fraudster is involved with the inventory count. If the fraudster participates in the count, he can falsify the recording of the true situation. False price adjustments would not have any inventory issues. There are some ingenious forms of register disbursement schemes perpetrated by employees. One example involves price guarantees. Customers are offered a refund of the price difference if the purchased item goes on sale within 30 days of purchase. The customer must bring in their receipt that has a barcode for scanning to qualify for the difference refund. Employees are very well aware of what will be going on sale next and if a customer purchases an item that will be going on sale soon, they might photocopy the receipt or take a picture of the barcode with their camera-capable smartphone. Most customers are not aware of the sale or do not bother going back to the store for the sales-price difference. The employee waits until near the end of the 30 days and then uses a copy of the barcode to generate the price-guarantee refund for him- or herself. Cash register or point-of-sale system records will still reconcile with the cash on hand. A legitimate sale is made and then the fraudster voids the sale. Funds received from the sale can then be appropriated by the fraudster. Typical controls for voids mandate that the original receipt should be attached to the voided sales. The salesperson can withhold the sales receipt from the customer to include with the voided sales records. If internal control is lax, lack of the original receipts can be overlooked during the daily sales reconciliation process. Normally managers are supposed to approve voids but may fail to do so. Some managers sign almost anything or may be colluding with the employee in the register scheme. Signatures are easily forged as little attention is given to comparing signatures. False voids create similar inventory problems just as the false return of goods does; inventory is lower than that recorded in the books. While book inventory is higher than the actual in-stock inventory levels, these types of schemes are not usually accompanied with a concealment scheme. Small inventory differences are usually ignored as some shrinkage is expected. Keeping the refunds, voids, and adjustments below certain levels may avoid review. The fraudster would have to have a number of these fraudulent transactions to total to any significant amounts, based on the low individual-transaction amounts. Fraudsters may destroy various types of documentation, not to conceal the fraud but to conceal who the fraudster is. Missing records makes identifying the fraudster much more difficult. Our case study will use two dBase files from the IDEA training course to demonstrate some practical tests. The “ED-Sales-2010-L4.DBF” file and the “ED-Sales-2011-L4.DBF” file are imported into IDEA and named “Sales-2010” and “Sales-2011” respectively. These files represent one location of a quick-service or fast-food hamburger chain. There are 18 fields in each of the files as outlined in Figure 12.1. Figure 12.1 Fields of the 2010 and 2011 Sales Files Since the data was imported into IDEA from a dBase file, the first field is always the DELETED field with a length of one. For both the “Sales-2011” file and the “Sales-2010” file, separately create three files, summarized by: The fields to total in each summarization include the BEFORE_TAX, SALES_TAX, and AFTER_TAX fields. For 2011, sales summarized by OP_ID are shown on the right side of Figure 12.2 and sales summarized by AUTH_ID are displayed on the left side of the figure. Figure 12.2 Summarization of the 2011 Sales by Authorizer and Summarized by Register Operator The results of the summarization by PAY_TYPE are shown in Figure 12.3 for the years 2011 and 2010. Figure 12.3 Summarized by Payment Type for 2011 and Summarized for 2010 A review of the payment type information for both years shows three significant areas of concern.

Register Disbursement Schemes

FALSE REFUNDS AND ADJUSTMENTS

FALSE REFUNDS AND ADJUSTMENTS

FALSE VOIDS

FALSE VOIDS

CONCEALMENT

CONCEALMENT

DATA ANALYTICAL TESTS

DATA ANALYTICAL TESTS

Data Familiarization