The Origin and Development of Stare Decisis at the U.S. Supreme Court

The Origin and Development of Stare Decisis at the U.S. Supreme Court

In the past few decades there has been a wealth of scholarship aimed at understanding the origin and development of institutional rules as agents of political, economic, and social change. In the eyes of many scholars, the questions of where institutions originate and how they develop are two of the most important puzzles confronting social science. Indeed, social scientists have spent a great deal of time trying to understand why institutional rules emerge, when and where they emerge, and the effects of their emergence on society. Existing literature examines the development of such political institutions as constitutions (Riker 1988; Tsebelis 1990), legislative rules (Bach and Smith 1988; Binder 1997; Jenkins, Crespin, and Carson 2005; McCubbins, Noll, and Weingast 1987; Shepsle 1986; Shipan 1995, 1996, 1997), and voting rules (Duverger 1954).

This scholarly interest in institutional rules stems from a general recognition that they can have pronounced effects on social outcomes—that is, they are not neutral but serve to allocate resources in society (Knight 1992; North 1990). Simply put, rules determine opportunities by defining choice sets and by giving strategic advantage to some actors over others. For instance, the rules of legislative debate in the U.S. House of Representatives often advantage one political party over the other and thus influence legislative outcomes (Binder 1996). More generally, rules provide the structure within which both government and nongovernmental actors make choices and, as a result, affect the distribution of political, social, and economic benefits. As North (1990, 30) argues, “Institutions are the rules of the game in society, or more formally, are the humanly devised constraints that shape human interaction.”

Our interest lies with understanding the quintessential institutional rule in the American judiciary—stare decisis. This informal norm directs judges to follow legal rulings from prior cases that are factually similar to ones being decided.1 It is the defining feature of American courts, and lawyers, judges, and scholars recognize it represents the most critical piece of American judicial infrastructure (Knight and Epstein 1996a; Powell 1990; Schauer 1987). Additionally, the transfer of the common law framework from England to the United States, and the role stare decisis plays within it, is the “central theme of early American legal history” (Flaherty 1969, 5). Indeed, put into place in the mid-eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the creation and development of this institutional structure represents a significant part of the American nation-building experience and serves as the most important transformational change in U.S. legal history (Friedman 1985; Hall 1989).

Despite the recognized centrality of stare decisis in the American judiciary, no social scientific study to date has endeavored to explain systematically why and when it developed. Instead, scholars generally discuss the purported advantages of stare decisis (e.g., stability, fairness, legitimacy, and efficiency) without reference to whether these factors were the motivating reasons for its adoption in the first place (Healy 2001; Knight and Epstein 1996a; Lee 1999; Schauer 1987). Additionally, while social scientists try to understand why judges follow precedent (e.g. Bueno de Mesquita and Stephenson 2002; Hansford and Spriggs 2006; Rasmusen 1994), they tend not to explain the origin of this rule (but see Heiner 1986; Shapiro 1972). Finally, most of the discussions of its origin and development come from legal historians (e.g. Allen 1964, 220–230; Friedman 1985, 124–126; Karsten 1997; Kempin 1959), who have not subjected their various conjectures to rigorous empirical tests.

Beyond the lack of a generalizable explanation for why it arose, scholars do not even agree on when the norm respecting precedent became institutionalized in the United States. Legal historians generally agree that the idea of past cases being binding did not exist prior to the late eighteenth century, but there is no consensus concerning when this norm became a routine part of legal decision-making. Some suggest that it was “firmly established” by the time of the American Revolution (Anastasoff v. United States 2000; Holdsworth 1934; Jones 1975, 452; Lee 1999; Price 2000). As Justice Story argued in his Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States, stare decisis was “in full view of the framers of the constitution” and “was required, and enforced in every state in the Union” (1833, § 378). Other legal historians, however, contend that the principle, at least as we know it today, did not develop until later in the nineteenth century. These scholars suggest during the pre-revolutionary period “the whole theory and practice of precedent was in a highly fluctuating condition” (Allen 1964, 209), and prior to somewhere between 1800 and 1850 American courts “had no firm doctrine of stare decisis” (Berman and Greiner 1966, 491–494; Caminker 1994; Healy 2001; Kempin 1959, 50).

This discussion leads to our central question: how, when, and why did the rule of treating prior cases as binding precedent emerge and develop in the United States? To answer this vitally important question, we argue that judges, desirous of increasing their policy-making authority, fostered stare decisis as a way to legitimize the judiciary and to insulate it from outside political attack. By doing so and by promoting the idea that judging is driven by neutral, legal considerations, rather than by politics, the judiciary gained a strengthened presence in the American political system. This argument is consistent with McGuire’s (2004) analysis, which indicates that as the Court institutionalized itself within the system of federal policy-making justices were better able to achieve their legal and policy objectives. It is also consistent with some historical work on the Marshall Court era, which contends that Chief Justice Marshall emphasized the rule of law as a way to bolster the Court’s authority (Knight and Epstein 1996b; Newmyer 1985).

To test our theoretical argument, the chapter proceeds as follows. In the next section we build the case that the U.S. Supreme Court began to base its decisions on its own precedents by the early 1800s and that such a norm was entrenched by 1815. We do so with two separate datasets. The first compares the Court’s use of English common law (that is, law developed through the decisions of England’s judges) to its citation of its own precedents and other American legal authorities (including lower court decisions and statutes) from 1791 to 1815. This initial analysis demonstrates the movement away from what had been the controlling legal rules in the form of English common law to the new rules set by American courts. From there we analyze the way in which the Court cites and interprets its own precedents from 1791 to 2005. By focusing on how the Court utilizes its own case law we can begin to pinpoint when the Court began to clearly invoke its own precedents to justify its decisions.

The Shift from Common Law to Supreme Court Precedent

To come to terms with how the United States institutionalized the use of, and respect for, American precedent, we analyze all Supreme Court cases decided between 1791 and 1815. The sample includes 706 cases, 275 of which include references to legal citations. Thus, our initial analysis focuses on these cases. Specifically, we read each opinion and coded all references to English common law, citations to federal and state statutes, citations to legal books, citations to Supreme Court precedents, citations to state and U.S. constitutional provisions, and citations to precedents from other courts in the United States. The key comparison for us is the movement of the Court toward its own precedents and rules and away from a reliance on English common law.

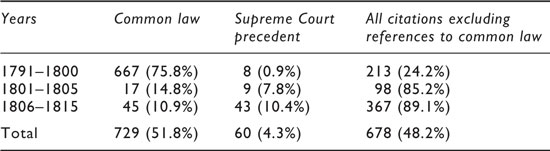

To give a sense of how the Court justified its decisions during its early years, Table 9.1 presents data on the types of legal citations the justices utilized in their decisions over our sample time period. Certainly, the justices of this era relied mostly on English common law (51.8% of citations), and little on their own precedents (4.3% of citations to authority). This is unsurprising given how few cases the Court decided in its early years. However, when we break down these citations between the early and later years of the sample, a different picture emerges.

Table 9.1 Types of Citations used by the U.S. Supreme Court, 1791–1815

Reference | Number (percent of total) |

English common law | 729 (51.8%) |

U.S. Supreme Court precedent | 60 (4.3%) |

Other U.S. court precedent (including lower federal courts, state supreme courts, and lower state courts) | 283 (20.1%) |

U.S. Constitution | 29 (2.1%) |

Federal statute | 103 (7.3%) |

State constitution | 7 (0.5%) |

State statute | 104 (7.4%) |

Other U.S. statute (e.g. local statutes) | 69 (4.9%) |

Legal book (not common law texts) | 23 (1.6%) |

Total | 1,407 (100.0%) |

As evident in Table 9.2, the Court’s use of English common law drops precipitously after 1800. Between the founding and 1800, nearly three-quarters of all citations were to the common law, but beginning in 1801 the balance shifts to sources other than the common law, which comprise about 85% of the cites. At that same time there is a sharp increase in the Court’s use of its own precedents, especially after 1806; more specifically, there was a 33% increase from 1801–1805 to 1806–1815. In fact, between 1806 and 1815 the Court makes almost as many references to its own precedents (43) as it does to common law (45). The other noteworthy aspect of Table 9.2 is that the Court cites U.S. legal authorities quite often in each time period. Whereas citations to English common law and Supreme Court decisions fluctuate from one period to the next, citations to other U.S. authorities never dip much below a quarter of the citations. Additionally, by the time the United States is about 20 years old the vast majority of citations are made to precedents set by American courts, to the federal and state constitutions, and to federal and state statutes.

Table 9.2 Comparison of Legal Citations by U.S. Supreme Court, 1791–1815

Note

The percentages in parentheses are based on citations within a period of time (or across rows).

At the case level, the results are similar. On average, the Court makes almost three references to English common law per case (with a standard deviation [S.D.] of 9.61). However, prior to 1800, this number stood at over five references per case (S.D. = 13.37), while after 1805 it fell to 0.32 references per case (S.D. = 1.98). In comparison, the Court referenced only 0.22 of its own precedents per case on average (S.D. = 0.66), but this number more than doubles to 0.46 references per case after 1805 (S.D. = 1.03). Finally, note that the Court makes almost two and a half references to all U.S. legal citations combined over the entire period of 1791 to 1815 (S.D. = 4.22), but the rate increased nearly 66% from the earliest period (1791–1800) to the latest period (1806–1815). This evidence, while not complete, highlights a movement away from reliance on English common law and toward a reliance on American law.

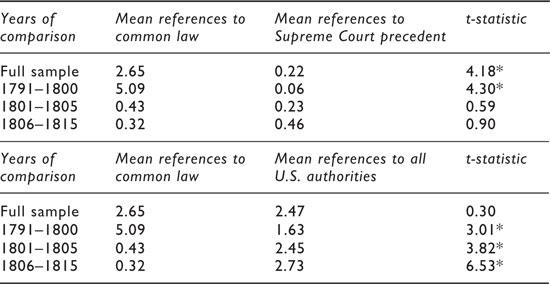

To further compare the change in the Court’s use of its own opinions and other American legal authorities to English common law, we examine the average number of such references per opinion across time. Specifically, we conduct difference of means tests to compare the average number of references to English common law with the average number of references to the Supreme Court’s own precedent, as well as a comparison of citations to English common law and the average number of citations to all other U.S. legal references. As reported in Table 9.3, there is a significant difference in citations of English common law, compared to Supreme Court precedent, in the earliest period, but thereafter the citation patterns are similar. In contrast, the citations to English common law, compared to all American authorities, changes even more substantially, with English common law constituting a considerably larger share of cites in the early period and American law constituting a larger share in the latter period.

Table 9.3 Comparisons of Mean Number of Citations to Supreme Court Precedent, 1791–1815

Note

* Difference significant at p <0.05.

Overall, these preliminary data indicate that, for the U.S. Supreme Court, English common law became less important over the first quarter century of its existence, while its own precedent, and precedent and legal authorities from within the United States (the state and federal constitutions, for example) became more important. While we do not show a complete picture here, our results suggest American precedent became a more relevant source of legal authority for the Supreme Court than English common law as the nation moved into the nineteenth century. This piece of the puzzle is key to understanding the development of the norm that Supreme Court justices should respect precedent.

The Court’s Use of Its Own Precedents

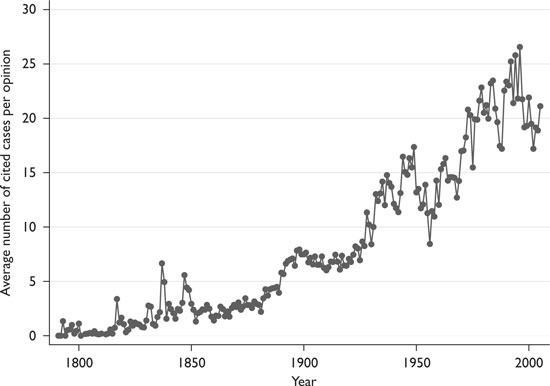

We next turn to an analysis of how the Supreme Court cited and interpreted its own precedents over time. Using Shepard’s Citations, we collected data on each time one of the Supreme Court’s majority opinions cited one of its earlier decided majority opinions. We relied on a comprehensive list of 26,751 orally argued signed or per curiam majority opinions of the Court released between 1791 and 2005, as identified by Fowler et al. (2007) and Black and Spriggs (2008). We then “shepardized” each of these cases to locate all subsequent citations to them in other majority opinions of the Court. Figure 9.1 displays the average number of Supreme Court opinions cited in the Court’s majority opinions released in each year. What we observe is a roughly linear increase in the number of citations to Court precedents, from an average of 1.1 cites in the first 50 years to an average of 18.7 citations in the last 50 years. This increase is one observable trait for the institutionalization of the norm of precedent at the Court over time.

Figure 9.1 The average number of Supreme Court precedents cited in majority opinions of the Court, 1791–2005.

Note

The authors collected these data from Shepard’s Citations.

In addition to examining citations to precedent, we also focus on the Court’s interpretation of its precedents. A legal interpretation is a reference to a case that goes beyond a mere legal citation and includes language in the opinion that has a potential legal effect on the cited case. While one can consider a legal citation as a latent judgment about the continuing relevance of the cited case, a legal interpretation goes further and subjects the cited case to legal analysis (see Hansford and Spriggs 2006). To gather these data we rely on Shepard’s Citations, which provide an “editorial analysis” for the potential legal effect each citing case has on each cited case.

Broadly speaking, legal interpretation takes two well-known forms. The Court can positively interpret a precedent by relying on the case as legal authority for the outcome of the citing case. Positive interpretation thus reinforces the legal vitality of a cited case and possibly expands its scope. Negative interpretation, by contrast, casts some doubt on the legal authority of a cited case by, at a minimum, indicating that it is inapplicable to the legal question at issue and, at the maximum, declaring that the precedent is no longer good law.

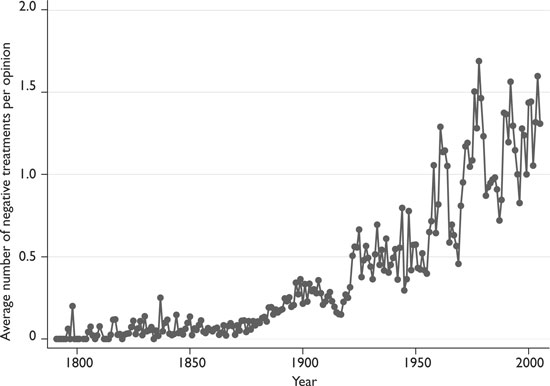

Our focus on legal interpretation follows from the norm of stare decisis